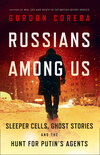

Kitabı oku: «Daniel Boone: The Pioneer of Kentucky», sayfa 12

CHAPTER XI.

Kentucky organized as a State

Peace with England.—Order of a Kentucky Court.—Anecdotes.—Speech of Mr. Dalton.—Reply of Piankashaw.—Renewed Indications of Indian Hostility.—Conventions at Danville.—Kentucky formed into a State.—New Trials for Boone.

The close of the war of the Revolution, bringing peace between the colonies and the mother country, deprived the Indians of that powerful alliance which had made them truly formidable. Being no longer able to obtain a supply of ammunition from the British arsenals, or to be guided in their murderous raids by British intelligence, they also, through their chiefs, entered into treaties of peace with the rapidly-increasing emigrants.

Though these treaties with the Indians prevented any general organization of the tribes, vagabond Indians, entirely lawless, were wandering in all directions, ever ready to perpetrate any outrage. Civil society has its highway robbers, burglars and murderers. Much more so was this the case among these savages, exasperated by many wrongs; for it cannot be denied that they were more frequently sinned against than sinning. Their untutored natures made but little distinction between the innocent and the guilty. If a vagabond white man wantonly shot an Indian—and many were as ready to do it as to shoot a wolf—the friends of the murdered Indian would take revenge upon the inmates of the first white man's cabin they encountered in the wilderness. Thus it was necessary for the pioneers to be constantly upon their guard. If they wandered any distance from the fort while hunting, or were hoeing in the field, or ventured to rear a cabin on a fertile meadow at a distance from the stations, they were liable to be startled at any hour of the day or of the night by the terrible war-whoop, and to feel the weight of savage vengeance.

This exposure to constant peril influenced the settlers, as a general rule, to establish themselves in stations. This gave them companionship, the benefits of co-operative labor, and security against any small prowling bands. These stations were formed upon the model of the one which Daniel Boone had so wisely organized at Boonesborough. They consisted of a cluster of bullet-proof log-cabins, arranged in a quadrangular form, so as to enclose a large internal area. All the doors opened upon this interior space. Here the cattle were gathered at night. The intervals between the cottages were filled with palisades, also bullet-proof. Loop-holes through the logs enabled these riflemen to guard every approach to their fortress. Thus they had little to fear from the Indians when sheltered by these strong citadels.

Emigration to Kentucky began very rapidly to increase. Large numbers crossed the mountains to Pittsburgh, where they took flat boats and floated down the beautiful Ohio, la belle rivière, until they reached such points on its southern banks as pleased them for a settlement, or from which they could ascend the majestic rivers of that peerless State. Comfortable homesteads were fast rising in all directions. Horses, cattle, swine, and poultry of all kinds were multiplied. Farming utensils began to make their appearance. The hum of happy industry was heard where wolves had formerly howled and buffalo ranged. Merchandise in considerable quantities was transported over the mountains on pack horses, and then floated down the Ohio and distributed among the settlements upon its banks. Country stores arose, land speculators appeared, and continental paper money became a circulating medium. This money, however, was not of any very great value, as may be inferred from the following decree, passed by one of the County Courts, establishing the schedule of prices for tavern-keeping:

"The Court doth set the following rates to be observed by keepers in this county: Whiskey, fifteen dollars the half-pint; rum, ten dollars the gallon; a meal, twelve dollars; stabling or pasturage, four dollars the night."

Under these changed circumstances, Colonel Boone, whose intrepidity nothing could daunt, and whose confidence in the protective power of his rifle was unbounded, had reared for himself, on one of the beautiful meadows of the Kentucky, a commodious home. He had selected a spot whose fertility and loveliness pleased his artistic eye.

It is estimated that during the years 1783 and 1784 nearly twelve thousand persons emigrated to Kentucky. Still all these had to move with great caution, with rifles always loaded, and ever on the alert against surprise. The following incident will give the reader an idea of the perils and wild adventures encountered by these parties in their search for new and distant homes.

Colonel Thomas Marshall, a man of much note in those days, had crossed the Alleghanies with his large family. At Pittsburgh he purchased a flat-boat, and was floating down the Ohio. He had passed the mouth of the Kanawha River without any incident of note occurring. About ten o'clock one night, as his boat had drifted near the northern shore of the solitary stream, he was hailed by a man upon the bank, who, after inquiring who he was, where he was bound, etc., added:

"I have been posted here by order of my brother, Simon Gerty, to warn all boats of the danger of permitting themselves to be decoyed ashore. My brother regrets very deeply the injury he has inflicted upon the white men, and to convince them of the sincerity of his repentance, and of his earnest desire to be restored to their society, he has stationed me here to warn all boats of the snares which are spread for them by the cunning of the Indians. Renegade white men will be placed upon the banks, who will represent themselves as in the greatest distress. Even children taken captive will be compelled, by threats of torture, to declare that they are all alone upon the shore, and to entreat the boats to come and rescue them.

"But keep in the middle of the river," said Gerty, "and steel your heart against any supplications you may hear."

The Colonel thanked him for his warning, and continued to float down the rapid current of the stream.

Virginia had passed a law establishing the town of Louisville, at the Falls of the Ohio. A very thriving settlement soon sprang up there.

The nature of the warfare still continuing between the whites and the Indians may be inferred from the following narrative, which we give in the words of Colonel Boone:

"The Indians continued to practice mischief secretly upon the inhabitants in the exposed part of the country. In October a party made an incursion into a district called Crab Orchard. One of these Indians having advanced some distance before the others, boldly entered the house of a poor defenseless family, in which was only a negro man, a woman and her children, terrified with apprehensions of immediate death. The savage, perceiving their defenseless condition, without offering violence to the family, attempted to capture the negro, who happily proved an over-match for him, and threw the Indian on the ground.

"In the struggle, the mother of the children drew an axe from the corner of the cottage and cut off the head of the Indian, while her little daughter shut the door. The savages soon appeared, and applied their tomahawks to the door. An old rusty gun-barrel, without a lock, lay in the corner, which the mother put through a small crevice, and the savages perceiving it, fled. In the meantime the alarm spread through the neighborhood; the armed men collected immediately and pursued the savages into the wilderness. Thus Providence, by means of this negro, saved the whole of the poor family from destruction."

The heroism of Mrs. Merrill is worthy of being perpetuated, not only as a wonderful achievement, but as illustrative of the nature of this dreadful warfare. Mr. Merrill, with his wife, little son and daughter, occupied a remote cabin in Nelson County, Kentucky. On the 24th of December, 1791, he was alarmed by the barking of his dog. Opening the door to ascertain the cause, he was instantly fired upon by seven or eight Indians who had crept near the house secreting themselves behind stumps and trees. Two bullets struck him, fracturing the bones both of his leg and of his arm. The savages, with hideous yells, then rushed for the door.

Mrs. Merrill had but just time to close and bolt it when the savages plunged against it and hewed it with their tomahawks. Every dwelling was at that time a fortress whose log walls were bullet proof. But for the terrible wounds which Mr. Merrill had received, he would with his rifle shooting through loop-holes, soon have put the savages to flight. They, emboldened by the supposition that he was killed, cut away at the door till they had opened a hole sufficiently large to crawl through. One of the savages attempted to enter. He had got nearly in when Mrs. Merrill cleft his skull with an ax, and he fell lifeless upon the floor. Another, supposing that he had safely effected an entrance, followed him and encountered the same fate. Four more of the savages were in this way despatched, when the others, suspecting that all was not right, climbed upon the roof and two of them endeavored to descend through the chimney. The noise they made directed the attention of the inmates of the cabin to the new danger.

There was a gentle fire burning upon the hearth. Mr. Merrill, with much presence of mind, directed his son, while his wife guarded the opening of the door with her ax, to empty the contents of a feather bed upon the fire. The dense smothering smoke filled the flue of the chimney. The two savages, suffocated with the fumes, after a few convulsive efforts to ascend fell almost insensible down upon the hearth. Mr. Merrill, seizing with his unbroken arm a billet of wood, despatched them both. But one of the Indians now remained. Peering in at the opening in the door he received a blow from the ax of Mrs. Merrill which severely wounded him. Bleeding and disheartened he fled alone into the wilderness, the only one of the eight who survived the conflict.

A white man who was at that time a prisoner among the Indians and who subsequently effected his escape, reported that when the wounded savage reached his tribe he said to the white captive in broken English:

"I have bad news for the poor Indian. Me lose a son, me lose a broder. The squaws have taken the breech clout, and fight worse than the long knives."

But the Indians were not always the aggressors. Indeed it is doubtful whether they would ever have raised the war-whoop against the white man, had it not been for the outrages they were so constantly experiencing from unprincipled and vagabond adventurers, who were ever infesting the frontiers. The following incident illustrates the character and conduct of these miscreants:

A party of Indian hunters from the South wandering through their ancient hunting grounds of Kentucky, accidentally came upon a settlement where they found several horses grazing in the field. They stole the horses, and commenced a rapid retreat to their own country. Three young men, Davis, Caffre and McClure, pursued them. Not being able to overtake the fugitives, they decided to make reprisals on the first Indians they should encounter. It so happened that they soon met three Indian hunters. The parties saluted each other in a friendly manner, and proceeded on their way in pleasant companionship.

The young men said that they observed the Indians conversing with one another in low tones of voice, and thus they became convinced that the savages meditated treachery. Resolving to anticipate the Indians' attack, they formed the following plan. While walking together in friendly conversation, the Indians being entirely off their guard, Caffre, who was a very powerful man, was to spring upon the lightest of the Indians, crush him to the ground, and thus take him a prisoner. At the same instant, Davis and McClure were each to shoot one of the other Indians, who, being thus taken by surprise, could offer no resistance.

The signal was given. Caffre sprang upon his victim and bore him to the ground. McClure shot his man dead. Davis' gun flashed in the pan. The Indian thus narrowly escaping death immediately aimed his gun at Caffre, who was struggling with the one he had grappled, and instantly killed him. McClure in his turn shot the Indian. There was now one Indian and two white men. But the Indian had the loaded rifle. McClure's was discharged and Davis' missed fire. The Indian, springing from the grasp of his dying antagonist, presented his rifle at Davis, who immediately fled, hotly pursued by the Indian. McClure, stopping only to reload his gun, followed after them. Soon he lost sight of both. Davis was never heard of afterwards. Doubtless he was shot by the avenging Indian, who returned to his wigwam with the white man's scalp.

McClure, after this bloody fray, being left alone in the wilderness, commenced a return to his distant home. He had not proceeded far before he met an Indian on horseback accompanied by a boy on foot. The warrior dismounted, and in token of peace offered McClure his pipe. As they were seated together upon a log, conversing, McClure said that the Indian informed him by signs that there were other Indians in the distance who would soon come up, and that then they should take him captive, tie his feet beneath the horse's belly and carry him off to their village. McClure seized his gun, shot the Indian through the heart, and plunging into the forest, effected his escape.

About this same time Captain James Ward, with a party of half a dozen white men, one of whom was his nephew, and a number of horses, was floating down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh. They were in a flat boat about forty-five feet long and eight feet wide. The gunwale of the boat consisted of but a single pine plank. It was beautiful weather, and for several days they were swept along by the tranquil stream, now borne by the changing current towards the one shore, and now towards the other. One morning when they had been swept by the stream within about one hundred and fifty feet of the northern shore, suddenly several hundred Indians appeared upon the bank, and uttering savage yells opened upon them a terrible fire.

Captain Ward's nephew, pierced by a ball in the breast, fell dead in the bottom of the boat. Every horse was struck by a bullet. Some were instantly killed; others, severely wounded, struggled so violently as to cause the frail bark to dip water, threatening immediate destruction. All the crew except Captain Ward were so panic-stricken by this sudden assault, that they threw themselves flat upon their faces in the bottom of the boat, and attempted no resistance where even the exposure of a hand would be the target for a hundred rifles.

Fortunately Captain Ward was protected from this shower of bullets by a post, which for some purpose had been fastened to the gunwale. He therefore retained his position at the helm, which was an oar, striving to guide the boat to the other side of the river. As the assailants had no canoes, they could not attempt to board, but for more than an hour they ran along the banks yelling and keeping up an almost constant fire. At length the boat was swept to the other side of the stream, when the miscreants abandoned the pursuit, and disappeared.

Quite a large party of emigrants were attacked by the Indians near what is now called Scagg's Creek, and six were instantly killed. A Mrs. McClure, delirious with terror, fled she knew not where, followed by her three little children and carrying a little babe in her arms. The cries of the babe guided the pursuit of the Indians. They cruelly tomahawked the three oldest children, and took the mother and the babe as captives. Fortunately the tidings of this outrage speedily reached one of the settlements. Captain Whitley immediately started in pursuit of the gang. He overtook them, killed two, wounded two, and rescued the captives. Such were the scenes enacted during a period of nominal peace with the Indians.

There has been transmitted to us a very curious document, giving an account of a speech made by Mr. Dalton, a Government agent, to a council of Indian chiefs, upon the announcement of peace with Great Britain, and their reply. Mr. Dalton said:

"My Children,—What I have often told you is now come to pass. This day I received news from my great chief at the Falls of the Ohio. Peace is made with the enemies of America. The white flesh, the Americans, French, and Spanish, this day smoked out of the peace-pipe. The tomahawk is buried, and they are now friends. I am told the Shawanese, the Delawares, Chickasaws, Cherokees, and all other red flesh, have taken the Long Knife by the hand. They have given up to them the prisoners that were in their hands.

"My children on the Wabash, open your ears and let what I tell you sink into your hearts. You know me. Near twenty years I have been among you. The Long Knife is my nation. I know their hearts. Peace they carry in one hand and war in the other. I leave you to yourselves to judge. Consider and now accept the one or the other. We never beg peace of our enemies. If you love your women and children, receive the belt of wampum I present you. Return me my flesh you have in your villages, and the horses you stole from my people in Kentucky. Your corn fields were never disturbed by the Long Knife. Your women and children lived quiet in their houses, while your warriors were killing and robbing my people. All this you know is the truth.

"This is the last time I shall speak to you. I have waited six moons to hear you speak and to get my people from you. In ten nights I shall leave the Wabash to see my great chief at the Falls of the Ohio, where he will be glad to hear from your own lips what you have to say. Here is tobacco I give you. Smoke and consider what I have said."

Mr. Dalton then presented Piankashaw, the chief of the leading tribe assembled in council, with a belt of blue and white wampum. Piankashaw received the emblem of peace with much dignity, and replied:

"My Great Father the Long Knife,—You have been many years among us. You have suffered by us. We still hope you will have pity and compassion upon us, on our women and children. The sun shines on us, and the good news of peace appears in our faces. This is the day of joy to the Wabash Indians. With one tongue we now speak. We accept your peace-belt.

"We received the tomahawk from the English. Poverty forced us to it. We were followed by other tribes. We are sorry for it. To-day we collect the scattered bones of our friends and bury them in one grave. We thus plant the tree of peace, that God may spread its branches so that we can all be secured from bad weather. Here is the pipe that gives us joy. Smoke out of it. Our warriors are glad you are the man we present it to. We have buried the tomahawk, have formed friendship never to be broken, and now we smoke out of your pipe.

"My father, we know that the Great Spirit was angry with us for stealing your horses and attacking your people. He has sent us so much snow and cold weather as to kill your horses with our own. We are a poor people. We hope God will help us, and that the Long Knife will have compassion on our women and children. Your people who are with us are well. We shall collect them when they come in from hunting. All the prisoners taken in Kentucky are alive. We love them, and so do our young women. Some of your people mend our guns, and others tell us they can make rum out of corn. They are now the same as we. In one moon after this we will take them back to their friends in Kentucky.

"My father, this being the day of joy to the Wabash Indians, we beg a little drop of your milk to let our warriors see that it came from your own breast. We were born and raised in the woods. We could never learn to make rum. God has made the white men masters of the world."

Having finished his speech, Piankashaw presented Mr. Dalton with three strings of blue and white wampum as the seal of peace. All must observe the strain of despondency which pervades this address, and it is melancholy to notice the imploring tones with which the chief asks for rum, the greatest curse which ever afflicted his people.

The incessant petty warfare waged between vagrant bands of the whites and the Indians, with the outrages perpetrated on either side, created great exasperation. In the year 1784 there were many indications that the Indians were again about to combine in an attack upon the settlements. These stations were widely scattered, greatly exposed, and there were many of them. It was impossible for the pioneers to rally in sufficient strength to protect every position. The savages, emerging unexpectedly from the wilderness, could select their own point of attack, and could thus cause a vast amount of loss and misery. For a long time it had been unsafe for any individual, or even small parties, unless very thoroughly armed, to wander beyond the protection of the forts. Under these circumstances, a convention was held of the leading men of Kentucky at the Danville Station, to decide what measures to adopt in view of the threatened invasion. It was quite certain that the movement of the savages would be so sudden and impetuous that the settlers would be compelled to rely mainly upon their own resources.

The great State of Virginia, of which Kentucky was but a frontier portion, had become rich and powerful. But many weary leagues intervened, leading through forests and over craggy mountains, between the plains of these distant counties and Richmond, the capital of Virginia. The convention at Danville discussed the question whether it were not safer for them to anticipate the Indians, and immediately to send an army for the destruction of their towns and crops north of the Ohio. But here they were embarrassed by the consideration that they had no legal power to make this movement, and that the whole question, momentous as it was and demanding immediate action, must be referred to the State Government, far away beyond the mountains. This involved long delay, and it could hardly be expected that the members of the General Court in their peaceful homes would fully sympathize with the unprotected settlers in their exposure to the tomahawk and the scalping knife.

Several conventions were held, and the question was earnestly discussed whether the interests of Kentucky did not require her separation from the Government of Virginia, and her organization as a self-governing State. The men who had boldly ventured to seek new homes so far beyond the limits of civilization were generally men of great force of character and of political foresight. They had just emerged from the war of the Revolution, during which all the most important questions of civil polity had been thoroughly canvassed. Their meetings were conducted with great dignity and calm deliberation.

On the twenty-third of May, 1785, the convention at Danville passed the resolve with great unanimity that Kentucky ought to be separated from Virginia, and received into the American Union, upon the same basis as the other States. Still that they might not act upon a question of so much importance without due deliberation, they referred the subject to another convention to be assembled at Danville in August. This convention reiterated the resolution of its predecessor; issued a proclamation urging the people everywhere to organise for defence against the Indians, and appointed a delegation of two members to proceed to Richmond, and present their request for a separation to the authorities there.

"The Legislature of Virginia was composed of men too wise not to see that separation was inevitable. Separated from the parent State by distance and by difficulties of communication, in those days most formidable, they saw that Kentuckians would not long submit to be ruled by those whose power was so far removed as to surround every approach to it with the greatest embarrassment. It was, without its wrongs, and tyranny and misgovernment, the repetition of the circumstances of the Crown and Colonies; and with good judgment, and as the beautiful language of the Danville convention expressed it, with sole intent to bless its people, they agreed to a dismemberment of its part, to secure the happiness of the whole."6

It is not important here to enter into a detail of the various discussions which ensued, and of the measures which were adopted. It is sufficient to say that the communication from Kentucky to the Legislature of Virginia was referred to the illustrious John Marshall, then at the commencement of his distinguished career. He gave to the request of the petitioners his own strong advocacy. The result was, that a decree was passed after tedious delays, authorising the formal separation of Kentucky from Virginia. On the fourth of February, 1791, the new State, by earnest recommendation of George Washington, was admitted into the American Union.

It does not appear that Colonel Boone was a member of any of these conventions. He had no taste for the struggles in political assemblies. He dreaded indeed the speculator, the land jobber, and the intricate decisions of courts, more than the tomahawk of the Indian. And he knew full well that should the hour of action come, he would be one of the first to be summoned to the field. While therefore others of the early pioneers were engaged in these important deliberations, he was quietly pursuing those occupations, congenial to his tastes, of cultivating the farm, or in hunting game in the solitude of the forests. His humble cabin stood upon the banks of the Kentucky River, not far from the station at Boonesborough. And thoroughly acquainted as he was with the habits of the Indians, he felt quite able, in his bullet-proof citadel, to protect himself from any marauding bands which might venture to show themselves so near the fort.

It seems to be the lot of humanity that life should be composed of a series of storms, rising one after another. In the palace and in the cottage, in ancient days and at the present time, we find the sweep of the inexorable law, that man is born to mourn.

"Sorrow is for the sons of men,

And weeping for earth's daughters."

The cloud of menaced Indian invasion had passed away, when suddenly the sheriff appears in Boone's little cabin, and informs him that his title to his land is disputed, and that legal proceedings were commenced against him. Boone could not comprehend this. Kentucky he regarded almost his own by the right of his discovery. He had led the way there. He had established himself and family in the land, and had defended it from the incursions of the Indians. And now, in his advancing years, to be driven from the few acres he had selected and to which he supposed he had a perfect title, seemed to him very unjust indeed. He could not recognise any right in what seemed to him but the quibbles of the lawyers. In his autobiography he wrote in reference to his many painful adventures:

"My footsteps have often been marked with blood. Two darling sons and a brother have I lost by savage hands, which have also taken from me forty valuable horses and abundance of cattle. Many dark and sleepless nights have I been a companion for owls, separated from the cheerful society of men, scorched by the summer's sun, and pinched by the winter's cold, an instrument ordained to settle the wilderness."

Agitated by the thought of the loss of his farm and deeply wounded in his feelings, as though a great wrong had been inflicted upon him, Boone addressed an earnest memorial to the Legislature of Kentucky. In this he stated that immediately after the troubles with the Indians had ceased, he located himself upon lands to which he supposed he had a perfect title; that he reared his house and commenced cultivating his fields. And after briefly enumerating the sacrifices he had made in exploring, settling and defending Kentucky, he said he could not understand the justice of making a set of complicated forms of law, superior to his actual occupancy of the land selected, as he believed when and where it was, it was his unquestioned right to do so.

But the lawyers and the land speculators were too shrewd for the pioneer. Colonel Boone was sued; the question went to the courts which he detested, and Boone lost his farm. It was indeed a very hard case. He had penetrated the country when no other white man trod its soil. He discovered its wonderful resources, and proclaimed them to the world. He had guided settlers into the region, and by his sagacity and courage, had provided for their wants and protected them from the savage. And now in his declining years he found himself driven from his farm, robbed of every acre, a houseless, homeless, impoverished man. The deed was so cruel that thousands since, in reading the recital, have been agitated by the strongest emotions of indignation and grief.