Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir»

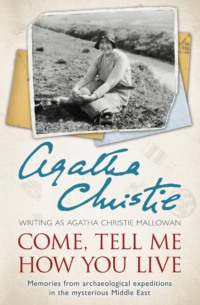

AGATHA CHRISTIE MALLOWAN

Come, Tell Me How You Live

With an Introduction

by Jacquetta Hawkes

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by

William Collins Sons & Co Ltd 1946

Copyright © Agatha Christie Mallowan 1946

Agatha Christie® copyright © Agatha Christie Limited. All rights reserved.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Cover photograph© Christie Archive Trust 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008129460

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 9780007487202

Version: 2017-04-11

To my husband, Max Mallowan; to the Colonel, Bumps, Mac and Guilford, this meandering chronicle is affectionately dedicated

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

A-Sitting on a Tell

Foreword

CHAPTER 1: Partant Pour la Syrie

CHAPTER 2: A Surveying Trip

CHAPTER 3: The Habur and the Jaghjagha

CHAPTER 4: First Season at Chagar Bazar

CHAPTER 5: Fin de Saison

CHAPTER 6: Journey’s End

CHAPTER 7: Life at Chagar Bazar

CHAPTER 8: Chagar and Brak

CHAPTER 9: Arrival of Mac

CHAPTER 10: The Trail to Raqqa

CHAPTER 11: Good-Bye to Brak

CHAPTER 12: ’Ain el ’Arus

Epilogue

Plate Section

Back Ads

Footnotes

Index

Also by Agatha Christie Mysteries

About the Publisher

Introduction

There are books that one reads with a persistent inner smile which from time to time becomes visible and occasionally audible. Come, Tell Me How You Live is one of them, and to read it is pure pleasure.

It was in 1930 that a happy chance had brought a young archaeologist, Max Mallowan, together with Agatha Christie, then already a well-known author. Visiting Baghdad, she had met Leonard and Katharine Woolley and accepted their invitation to stay with them at Ur where they had been digging for several seasons. Max, their assistant, was charged to escort Agatha homeward, sight-seeing on the way. Thus agreeably thrown together they were to be married before the end of the year and so to enter their long and extraordinarily creative union.

Agatha did not see her own renown as any bar to sharing in her husband’s work. From the first she took a full part in every one of Max’s excavations in Syria and Iraq, enduring discomforts and finding comedy in all such disasters as an archaeologist is heir to. Inevitably her personal acquaintance, who knew nothing of the mysteries of digging in foreign lands, asked her what this strange life was like—and she determined to answer their questions in a light-hearted book.

Agatha began Come, Tell Me How You Live before the war, and although she was to lay it aside during four years of war-work, in both spirit and content it belongs to the thirties. Like the balanced, bien élevée bourgeoise that she was, she did not think the tragedies of human existence more significant than its comedies and delights. Nor at that time was archaeology in the Middle East weighed down with science and laborious technique. It was a world where one mounted a Pullman at Victoria in a ‘big snorting, hurrying, companionable train, with its big, puffing engine’, was waved away by crowds of relatives, at Calais caught the Orient Express to Istanbul, and so arrived at last in a Syria where good order, good food and generous permits for digging were provided by the French. Moreover, it was a world where Agatha could make fun of the Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, Turks and Yezidi devil-worshippers who worked on the excavations as freely as she could of Oxford scholars, of her husband and herself.

The author calls her book, ‘small beer… full of everyday doings and happenings’ and an ‘inconsequent chronicle’. In fact it is most deftly knit together, making a seamless fabric of five varied seasons in the field. These began late in 1934 with a survey of the ancient city mounds, or tells, studding the banks of the Habur in northern Syria—its purpose being to select the most promising for excavation.

Max showed his sound judgement in choosing Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak out of the fifty Come, Tell Me How You Live examined, for both, when excavated during the four following seasons, added vastly to our knowledge of early Mesopotamia. Agatha, on her side, showed characteristic discipline by denying herself all archaeological particularities in her book, so preserving its lightness and consistency.

In the primitive and culture-clashing conditions of the time and place ‘everyday doings and happenings’ were sufficiently extraordinary to occupy the reader: men and machines were equally liable to give trouble, and so, too, did mice, bats, spiders, fleas and the stealthy carriers of what was then called Gippy tummy. Not only is episode after episode most amusingly told, but there emerges from the telling some excellent characterisation. If Agatha Christie the detective writer can be said to have taken characters out of a box, here in a few pages she shows how deftly she could bring individuals to life.

One interesting subject which the author, in her modesty, has not sufficiently emphasized is the very considerable part she played in the practical work of the expeditions. She mentions in passing her struggles to produce photographs without a darkroom and her labelling of finds, but that is not enough. When, later, I was fortunate enough to spend a week with the Mallowans at Nimrud, near Mosul, I was surprised how much she did in addition to securing domestic order and good food. At the beginning of each season she would retire to her own little room to write, but as soon as the pressure of work on the dig had mounted she shut the door on her profession and devoted herself to antiquity. She rose early to go the rounds with Max, catalogued and labelled, and on this occasion busied herself with the preliminary cleaning of the exquisite ivories which were coming from Fort Shalmaneser. I have a vivid picture of her confronting one of these carvings, with her dusting brush poised and head tilted, smiling quizzically at the results of her handiwork.

This remembered moment adds to my conviction that although she gave so much time to it, Agatha Christie remained inwardly detached from archaeology. She relished the archaeological life in remote country and made good use of its experiences in her own work. She had a sound knowledge of the subject, yet remained outside it, a happily amused onlooker.

That Agatha could find intense enjoyment from the wild Mesopotamian countryside and its peoples emerges from many of the pages of Come, Tell Me How You Live. There is, for one instance, her account of the picnic when she and Max sat among flowers on the lip of a little volcano. ‘The utter peace is wonderful. A great wave of happiness surges over me, and I realize how much I love this country, and how complete and satisfying this life is…’ So, in her short Epilogue looking back across the war years to recall the best memories of the Habur she declares: ‘Writing this simple record has not been a task, but a labour of love.’ This is evidently true, for some radiance lights all those everyday doings however painful or absurd. It is a quality which explains why, as I said at the beginning, this book is a pure pleasure to read.

JACQUETTA HAWKES

1983

A-SITTING ON A TELL

(With apologies to Lewis Carroll)

I’ll tell you everything I can

If you will listen well:

I met an erudite young man

A-sitting on a Tell.

‘Who are you, sir?’ to him I said,

‘For what is it you look?’

His answer trickled through my head

Like bloodstains in a book.

He said: ‘I look for aged pots

Of prehistoric days,

And then I measure them in lots

And lots of different ways.

And then (like you) I start to write,

My words are twice as long

As yours, and far more erudite.

They prove my colleagues wrong!’

But I was thinking of a plan

To kill a millionaire

And hide the body in a van

Or some large Frigidaire.

So, having no reply to give,

And feeling rather shy,

I cried: ‘Come, tell me how you live!

And when, and where, and why?’

His accents mild were full of wit:

‘Five thousand years ago

Is really, when I think of it,

The choicest Age I know.

And once you learn to scorn A.D.

And you have got the knack,

Then you could come and dig with me

And never wander back.’

But I was thinking how to thrust

Some arsenic into tea,

And could not all at once adjust

My mind so far B.C.

I looked at him and softly sighed,

His face was pleasant too…

‘Come, tell me how you live?’ I cried,

‘And what it is you do?’

He said: ‘I hunt for objects made

By men where’er they roam,

I photograph and catalogue

And pack and send them home.

These things we do not sell for gold

(Nor yet, indeed, for copper!),

But place them on Museum shelves

As only right and proper.

‘I sometimes dig up amulets

And figurines most lewd,

For in those prehistoric days

They were extremely rude!

And that’s the way we take our fun,

’Tis not the way of wealth.

But archaeologists live long

And have the rudest health.’

I heard him then, for I had just

Completed a design

To keep a body free from dust

By boiling it in brine.

I thanked him much for telling me

With so much erudition,

And said that I would go with him

Upon an Expedition…

And now, if e’er by chance I dip

My fingers into acid,

Or smash some pottery (with slip!)

Because I am not placid,

Or if I see a river flow

And hear a far-off yell,

I sigh, for it reminds me so

Of that young man I learned to know—

Whose look was mild, whose speech was slow,

Whose thoughts were in the long ago,

Whose pockets sagged with potsherds so,

Who lectured learnedly and low,

Who used long words I didn’t know,

Whose eyes, with fervour all a-glow,

Upon the ground looked to and fro,

Who sought conclusively to show

That there were things I ought to know

And that with him I ought to go

And dig upon a Tell!

Foreword

This book is an answer. It is the answer to a question that is asked me very often.

‘So you dig in Syria, do you? Do tell me all about it. How do you live? In a tent?’ etc., etc.

Most people, probably, do not want to know. It is just the small change of conversation. But there are, now and then, one or two people who are really interested.

It is the question, too, that Archaeology asks of the Past—Come, tell me how you lived?

And with picks and spades and baskets we find the answer.

‘These were our cooking pots.’ ‘In this big silo we kept our grain.’ ‘With these bone needles we sewed our clothes.’ ‘These were our houses, this our bathroom, here our system of sanitation!’ ‘Here, in this pot, are the gold earrings of my daughter’s dowry.’ ‘Here, in this little jar, is my make-up.’ ‘All these cook-pots are of a very common type. You’ll find them by the hundred. We get them from the Potter at the corner. Woolworth’s, did you say? Is that what you call him in your time?’

Occasionally there is a Royal Palace, sometimes a Temple, much more rarely a Royal burial. These things are spectacular. They appear in newspapers in headlines, are lectured about, shown on screens, everybody hears of them! Yet I think to one engaged in digging, the real interest is in the everyday life—the life of the potter, the farmer, the tool-maker, the expert cutter of animal seals and amulets—in fact, the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker.

A final warning, so that there will be no disappointment. This is not a profound book—it will give you no interesting sidelights on archaeology, there will be no beautiful descriptions of scenery, no treating of economic problems, no racial reflections, no history.

It is, in fact, small beer—a very little book, full of everyday doings and happenings.

AGATHA CHRISTIE MALLOWAN

CHAPTER 1

Partant pour la Syrie

In a few weeks’ time we are starting for Syria!

Shopping for a hot climate in autumn or winter presents certain difficulties. One’s last year’s summer clothes, which one has optimistically hoped will ‘do’, do not ‘do’ now the time has come. For one thing they appear to be (like the depressing annotations in furniture removers’ lists) ‘Bruised, Scratched and Marked’. (And also Shrunk, Faded and Peculiar!) For another—alas, alas that one has to say it!—they are too tight everywhere.

So—to the shops and the stores, and:

‘Of course, Modom, we are not being asked for that kind of thing just now! We have some very charming little suits here—O.S. in the darker colours.’

Oh, loathsome O.S.! How humiliating to be O.S.! How even more humiliating to be recognized at once as O.S.!

(Although there are better days when, wrapped in a lean long black coat with a large fur collar, a saleswoman says cheeringly:

‘But surely Modom is only a Full Woman?’)

I look at the little suits, with their dabs of unexpected fur and their pleated skirts. I explain sadly that what I want is a washing silk or cotton.

‘Modom might try Our Cruising Department.’

Modom tries Our Cruising Department—but without any exaggerated hopes. Cruising is still enveloped in the realms of romantic fancy. It has a touch of Arcady about it. It is girls who go cruising—girls who are slim and young and wear uncrushable linen trousers, immensely wide round the feet and skintight round the hips. It is girls who sport delightfully in Play Suits. It is girls for whom Shorts of eighteen different varieties are kept!

The lovely creature in charge of Our Cruising Department is barely sympathetic.

‘Oh, no, Modom, we do not keep out-sizes.’ (Faint horror! Outsizes and Cruising? Where is the romance there?)

She adds:

‘It would hardly be suitable, would it?’

I agree sadly that it would not be suitable.

There is still one hope. There is Our Tropical Department.

Our Tropical Department consists principally of Topees—Brown Topees, White Topees; Special Patent Topees. A little to one side, as being slightly frivolous, are Double Terais, blossoming in pinks and blues and yellows like blooms of strange tropical flowers. There is also an immense wooden horse and an assortment of jodhpurs.

But—yes—there are other things. Here is suitable wear for the wives of Empire Builders. Shantung! Plainly cut shantung coats and skirts—no girlish nonsense here—bulk is accommodated as well as scragginess! I depart into a cubicle with various styles and sizes. A few minutes later I am transformed into a memsahib!

I have certain qualms—but stifle them. After all, it is cool and practical and I can get into it.

I turn my attention to the selection of the right kind of hat. The right kind of hat not existing in these days, I have to have it made for me. This is not so easy as it sounds.

What I want, and what I mean to have, and what I shall almost certainly not get, is a felt hat of reasonable proportions that will fit on my head. It is the kind of hat that was worn some twenty years ago for taking the dogs for a walk or playing a round of golf. Now, alas, there are only the Things one attaches to one’s head—over one eye, one ear, on the nape of one’s neck—as the fashion of the moment dictates—or the Double Terai, measuring at least a yard across.

I explain that I want a hat with a crown like a Double Terai and about a quarter of its brim.

‘But they are made wide to protect fully from the sun, Modom.’

‘Yes, but where I am going there is nearly always a terrific wind, and a hat with a brim won’t stay on one’s head for a minute.’

‘We could put Modom on an elastic.’

‘I want a hat with a brim no larger than this that I’ve got on.’

‘Of course, Modom, with a shallow crown that would look quite well.’

‘Not a shallow crown! The hat has got To Keep On!’

Victory! We select the colour—one of those new shades with the pretty names: Dirt, Rust, Mud, Pavement, Dust, etc.

A few minor purchases—purchases that I know instinctively will either be useless or land me in trouble. A Zip travelling bag, for instance. Life nowadays is dominated and complicated by the remorseless Zip. Blouses zip up, skirts zip down, ski-ing suits zip everywhere. ‘Little frocks’ have perfectly unnecessary bits of zipping on them just for fun.

Why? Is there anything more deadly than a Zip that turns nasty on you? It involves you in a far worse predicament than any ordinary button, clip, snap, buckle or hook and eye.

In the early days of Zips, my mother, thrilled by this delicious novelty, had a pair of corsets fashioned for her which zipped up the front. The results were unfortunate in the extreme! Not only was the original zipping-up fraught with extreme agony, but the corsets then obstinately refused to de-zip! Their removal was practically a surgical operation! And owing to my mother’s delightful Victorian modesty, it seemed possible for a while that she would live in these corsets for the remainder of her life—a kind of modern Woman in the Iron Corset!

I have therefore always regarded the Zip with a wary eye. But it appears that all travelling bags have Zips.

‘The old-fashioned fastening is quite superseded, Modom,’ says the salesman, regarding me with a pitying look.

‘This, you see, is so simple,’ he says, demonstrating.

There is no doubt about its simplicity—but then, I think to myself, the bag is empty.

‘Well,’ I say, sighing, ‘one must move with the times.’

With some misgivings I buy the bag.

I am now the proud possessor of a Zip travelling bag, an Empire Builder’s Wife’s coat and skirt, and a possibly satisfactory hat.

There is still much to be done.

I pass to the Stationery Department. I buy several fountain and stylographic pens—it being my experience that, though a fountain pen in England behaves in an exemplary manner, the moment it is let loose in desert surroundings it perceives that it is at liberty to go on strike and behaves accordingly, either spouting ink indiscriminately over me, my clothes, my notebook and anything else handy, or else coyly refusing to do anything but scratch invisibly across the surface of the paper. I also buy a modest two pencils. Pencils are, fortunately, not temperamental, and though given to a knack of quiet disappearance, I have always a resource at hand. After all, what is the use of an architect if not to borrow pencils from?

Four wrist-watches is the next purchase. The desert is not kind to watches. After a few weeks there, one’s watch gives up steady everyday work. Time, it says, is only a mode of thought. It then takes its choice between stopping eight or nine times a day for periods of twenty minutes, or of racing indiscriminately ahead. Sometimes it alternates coyly between the two. It finally stops altogether. One then goes on to wrist-watch No. 2, and so on. There is also a purchase of two four and six watches in readiness for that moment when my husband will say to me: ‘Just lend me a watch to give to the foreman, will you?’

Our Arab foremen, excellent though they are, have what might be described as a heavy hand with any kind of timepiece. Telling the time, anyway, calls for a good deal of mental strain on their part. They can be seen holding a large round moon-faced watch earnestly upside down, and gazing at it with really painful concentration while they get the answer wrong! Their winding of these treasures is energetic and so thorough that few mainsprings can stand up to the strain!

It therefore happens that by the end of the season the watches of the expedition staff have been sacrificed one by one. My two four and six watches are a means of putting off the evil day.

Packing!

There are several schools of thought as to packing. There are the people who begin packing at anything from a week or a fortnight beforehand. There are the people who throw a few things together half an hour before departure. There are the careful packers, insatiable for tissue paper! There are those who scorn tissue paper and just throw the things in and hope for the best! There are the packers who leave practically everything that they want behind! And there are the packers who take immense quantities of things that they never will need!

One thing can safely be said about an archaeological packing. It consists mainly of books. What books to take, what books can be taken, what books there are room for, what books can (with agony!) be left behind. I am firmly convinced that all archaeologists pack in the following manner: They decide on the maximum number of suitcases that a long-suffering Wagon Lit Company will permit them to take. They then fill these suitcases to the brim with books. They then, reluctantly, take out a few books, and fill in the space thus obtained with shirt, pyjamas, socks, etc.

Looking into Max’s room, I am under the impression that the whole cubic space is filled with books! Through a chink in the books I catch sight of Max’s worried face.

‘Do you think,’ he asks, ‘that I shall have room for all these?’

The answer is so obviously in the negative that it seems sheer cruelty to say it.

At four-thirty p.m. he arrives in my room and asks hopefully:

‘Any room in your suitcases?’

Long experience should have warned me to answer firmly ‘No,’ but I hesitate, and immediately doom falls upon me.

‘If you could just get one or two things—’

‘Not books?’

Max looks faintly surprised and says: ‘Of course books—what else?’

Advancing, he rams down two immense tomes on top of the Empire Builder’s Wife’s suit which has been lying smugly on top of a suitcase.

I utter a cry of protest, but too late.

‘Nonsense,’ says Max, ‘lots of room!’ And forces down the lid, which refuses spiritedly to shut.

‘It’s not really full even now,’ says Max optimistically.

He is, fortunately, diverted at this moment by a printed linen frock lying folded in another suitcase. ‘What’s that?’

I reply that it is a dress.

‘Interesting,’ says Max. ‘It’s got fertility motifs all down the front.’

One of the more uncomfortable things about being married to an archaeologist is their expert knowledge of the derivation of the most harmless-looking patterns!

At five-thirty Max casually remarks that he’d better go out and buy a few shirts and socks and things. He returns three-quarters of an hour later, indignant because the shops all shut at six. When I say they always do, he replies that he had never noticed it before.

Now, he says, he has nothing to do but ‘clear up his papers’.

At eleven p.m. I retire to bed, leaving Max at his desk (never to be tidied or dusted under the most dire penalties), up to the elbows in letters, bills, pamphlets, drawings of pots, innumerable potsherds, and various match-boxes, none of them containing matches, but instead odd beads of great antiquity.

At four a.m. he comes excitedly into the bedroom, cup of tea in hand, to announce that he has at last found that very interesting article on Anatolian finds which he had lost last July. He adds that he hopes that he hasn’t woken me up.

I say that of course he has woken me up, and he’d better get me a cup of tea too!

Returning with the tea, Max says he has also found a great many bills which he thought he had paid. I, too, have had that experience. We agree that it is depressing.

At nine a.m. I am called in as the heavy-weight to sit on Max’s bulging suitcases.

‘If you can’t make them shut,’ says Max ungallantly, ‘nobody can!’

The superhuman feat is finally accomplished by the aid of sheer avoirdupois, and I return to contend with my own difficulty, which is, as prophetic vision had told me it would be, the Zip bag. Empty in Mr Gooch’s shop, it had looked simple, attractive, and labour-saving. How merrily then had the Zip run to and fro! Now, full to the brim, the closing of it is a miracle of superhuman adjustment. The two edges have to be brought together with mathematical precision, and then, just as the Zip is travelling slowly across, complications set in, due to the corner of a sponge-bag. When at last it closes, I vow not to open it again until I get to Syria!

On reflection, however, this is hardly possible. What about the aforementioned sponge-bag? Am I to travel for five days unwashed? At the moment even that seems preferable to unzipping the Zip bag!

Yes, now the moment has come and we are really off. Quantities of important things have been left undone: the Laundry, as usual, has let us down; the Cleaners, to Max’s chagrin, have not kept their promises—but what does anything matter? We are going!

Just for a moment or two it looks as though we aren’t going! Max’s suitcases, delusive in appearance, are beyond the powers of the taximan to lift. He and Max struggle with them, and finally, with the assistance of a passer-by, they are hoisted on to the taxi.

We drive off for Victoria.

Dear Victoria—gateway to the world beyond England—how I love your continental platform. And how I love trains, anyway! Snuffing up the sulphurous smell ecstatically—so different from the faint, aloof, distantly oily smell of a boat, which always depresses my spirits with its prophecy of nauseous days to come. But a train—a big snorting, hurrying, companionable train, with its big puffing engine, sending up clouds of steam, and seeming to say impatiently: ‘I’ve got to be off, I’ve got to be off, I’ve got to be off!’—is a friend! It shares your mood, for you, too, are saying: ‘I’m going to be off, I’m going, I’m going, I’m going…’

By the door of our Pullman, friends are waiting to see us off. The usual idiotic conversations take place. Famous last words pour from my lips—instructions about dogs, about children, about forwarding letters, about sending out books, about forgotten items, ‘and I think you’ll find it on the piano, but it may be on the bathroom shelf’. All the things that have been said before, and do not in the least need saying again!

Max is surrounded by his relations, I by mine.

My sister says tearfully that she has a feeling that she will never see me again. I am not very much impressed, because she has felt this every time I go to the East. And what, she asks, is she to do if Rosalind gets appendicitis? There seems no reason why my fourteen-year-old daughter should get appendicitis, and all I can think of to reply is: ‘Don’t operate on her yourself!’ For my sister has a great reputation for hasty action with her scissors, attacking impartially boils, haircutting, and dressmaking—usually, I must admit, with great success.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.