Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Between the Sticks»

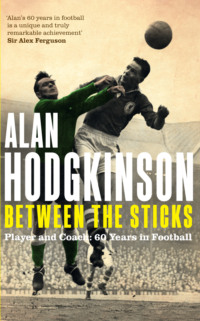

Between the Sticks

Alan Hodgkinson MBE

WHAT THEY SAY ABOUT ‘HODGEY’

For sixty years Alan has operated at the highest level of football. People talk of legends of sport, but often the term is used without the recipient having the credibility and stature to merit such a description. In the case of Alan Hodgkinson there is absolutely no doubt he is truly deserving of the accolade.

Craig Brown

He was not only a great goalkeeper but a county level cricketer and squash player. Alan was one of the great goalkeepers in an era of great goalkeepers. His experience and contacts in the game are second to none. The best goalkeeping coach there is.

Jim Smith

Alan was my goalkeeping coach and played a highly significant role in my career at Manchester United, coaching me and offering me the benefit of his unparalleled expertise and experience. He helped me mature and settle into a much higher grade of football than I had been used to. I shall be forever grateful to him.

Peter Schmeichel

Alan was not only my first professional goalkeeping coach, he was THE first goalkeeping coach. He was instrumental in helping me as a goalkeeper and ultimately as a goalkeeping coach. He is a very special man both on and off the field.

Eric Steele, Senior Goalkeeping Coach, Manchester United

He was more than the club’s goalkeeper, he was part of the match day at Bramall Lane. He was a local lad who knew his audience. He was a remarkable player. His reflexes defied explanation and his bravery was never in question. Few players in the history of Sheffield United are remembered with as much affection as ‘Hodgey’.

Sean Bean, actor

Having worked with Alan at the highest level I consider myself privileged to have witnessed his preparation, organisation and attention to detail. He has been totally dedicated to the art and science of his trade – he’s a one-off.

Gordon Milne

The specialist work Alan did with the Scotland goalkeepers was outstanding. The fact he worked for the Scottish FA for 17 years is testament to his quality of coaching. He transformed top goalkeepers in Scotland. A brilliant goalkeeping coach.

Andy Roxburgh

Alan was one of my boyhood heroes. All these years on, nothing has changed in that respect. He is a modest, warm, fine man and a true Blades legend. He is always welcome at Bramall Lane – his spiritual home.

Kevin McCabe, Chairman, Sheffield United FC

Alan worked for me for several years as goalkeeping coach and was a conscientious worker. He set excellent standards for every goalkeeper he coached based on technique and hard work. His most important role was on deciding the potential of a young Danish goalkeeper. When Alan kept coming back with better and better reports I had to put the question to him, one that had always bothered me regarding Continental goalkeepers, ‘Can he play in the English game?’ Alan replied, ‘He will be an absolute certainty at Manchester United.’ That was Peter Schmeichel – enough said.

Sir Alex Ferguson

Alan was the first professional goalkeeping coach. In 1981–82 when Watford gained promotion to what was then Division One, I made one of my best ever managerial decisions. I appointed him as our goalkeeping coach. He was a top-class goalkeeper who became a top-class coach, but, just as importantly, he is a top-class man.

Graham Taylor

I can never recall Hodgey wearing gloves. Yet the ball stuck to his hands like a Teflon coating to a pan. He was a great goalkeeper in an era when England produced truly great goalkeepers.

Jimmy Greaves

When Alan played at Goodison Park he would often take a young lad from the crowd and invite the lad to ‘keep goal’ with him in the pre-match kick-in. I’m sure the lad never forgot the experience and Everton fans appreciated it too. You can’t imagine such a thing happening these days, football is bereft of such simple, yet wonderful gestures towards ordinary fans.

Jimmy Gabriel, Everton FC

Hodgey was a truly superb goalkeeper. I was recently asked if Alan was better than the goalkeepers we now see in the Premier League. I had to be honest and say, ‘Not quite … then again, Alan has turned 76!’

Tommy Smith

Sixty years in professional football is a truly remarkable achievement. Alan Hodgkinson is unique and the longevity of his career in football may never be bettered.

Michel Platini

Hodgey is the ‘daddy’ of all goalkeeping coaches. He instigated and created the content for the UEFA Goalkeeping Licences. His expertise and experience are respected throughout the world.

Ian Rush

Sixty years in professional football is a phenomenal achievement. Alan has not simply ‘worked with’ the best, his efforts and expertise made those goalkeepers the best.

Paul Ince

It was said I developed into a ‘world class’ goalkeeper. If that’s true, then I owe it all to Alan Hodgkinson. The best goalkeeping coach in the world.

Andy Goram

A superb goalkeeper, Hodgey was not content with that, he went on to become arguably the best goalkeeping coach there has ever been.

Gordon Banks

This book is dedicated to Brenda, the love of my life, and to our loving family.

What They Say About ‘Hodgey’

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘It is a wise man that knows his own child.’

The Merchant of Venice

14 October 1967: George Best at Bramall Lane

In 1967, George Best had it all. There is hardly anything that can be done with a football that Best could not do. He is part of an elite group that includes Pele, Johan Cruyff, Diego Maradona, Stanley Matthews and Lionel Messi, players who have taken their place in the pantheon of the football gods.

Genius is a word bandied around far too often in football, but for George it was wholly appropriate. And he was, of course, unbelievably handsome. Teenage girls worshipped him, and women of all ages adored him. There are some people who look effortlessly stylish and elegant no matter what they wear – dress them in an old potato sack and they’ll still exude elan. George was such a person. It was this heady cocktail of football genius and dashing good looks (along with the fact that he was a really nice guy) that resulted in George being the first footballer to achieve fame outside the game. I remember, how, on a visit to France in the sixties, I saw George on the cover of Paris Match and thought, ‘This lad has really made it.’

It is for his genius as a footballer that I like to remember George. For me, his secret weapon was his acceleration. In all my years in the sport I have never seen a footballer move as fast as Best from a standing start – not Alan Shearer, Thierry Henry, Robin Van Persie; no one. When it comes to leaving your marker for dead, the first three yards are the most important, and the first yard is in your head. Add in the skill, agility and dexterity that throws opponents off balance and George became uncatchable.

I have never come across a player, then or since, who did it all so easily and, apparently, instinctively. George was a superb exponent of the almost lost art of dribbling. He scribbled football history with his feet and it was nothing to see him leave four, even five men standing off-balance and bemused.

Countless words have been written and spoken about George’s genius as a footballer. All of them wholly deserved. One thing I have never heard mentioned, however, was how thick and effective his neck muscles were. The power he generated from the neck enabled him to head a ball as well as the most potent striker or towering centre-back, and he was strong enough to look after himself when the going got tough, as it often did for him.

What is also often overlooked about George’s game is that he was a terrific defender and tackler. It was part of his job to track back and defend, and he did so to tremendous effect. But it was for his audacious attacking flair that he was best known and loved, and it was this skill that left an indelible mark on the minds of all who were lucky enough to see him play.

When George burst onto the international scene as a teenager with Northern Ireland, the former Spurs and Northern Ireland captain Danny Blanchflower was approached outside Windsor Park by Daily Mirror football reporter Vince Wilson and asked for his opinion of the young George Best. Most players would have replied with a list of insipid superlatives. Not the astute, aesthetic and articulate Blanchflower, the Oscar Wilde of Windsor Park.

‘George makes a greater appeal to the senses than Stan Matthews or Tom Finney did,’ said Danny, in characteristic fashion. ‘His movements are quicker, lighter, more balletic. He offers grander surprises to the mind and eye. Though seemingly insouciant on the pitch, he has ice in his veins, warmth in his heart and hitherto unseen timing and balance in his feet.’

Vince Wilson looked up from his notebook, somewhat agitated.

‘Yes, yes, yes, Danny,’ said Vince, pen still poised, ‘but do you rate Best as a player?’

I played against George on numerous occasions and was lucky enough to observe at first hand his development from teenager of outstanding natural talent to a true football genius. In October 1967, following a game at Stoke, I chatted to Gordon Banks about Best, because Manchester United were Sheffield United’s next opponents.

‘United play to his speed,’ Gordon informed me. ‘When we played them, Charlton and Crerand played the ball through the channels between and behind our back four for George to run on to. He times his runs to perfection, so he doesn’t get offside. He’s like lightning. He leaves defenders in his wake. You’re left with a one-on-one with him. He’ll really test you because he’s ice cool, clever, unbelievably skilful and very, very quick.’

I always felt that one of the strongest aspects of my game was when faced one-on-one with an advancing forward. I had, over the years, spent countless hours on the training ground working to improve that ability. In the 1960s clubs did not have specialist goalkeeping coaches. I did the normal daily training with the rest of the first-team squad but felt I needed more. As there was no one at Sheffield United to help me in this, I did it myself, mostly in the afternoons. Keepers at other clubs were also developing their skills, making what, in essence, was a journey of self-discovery, among them Tony Waiters (Blackpool), Peter Bonetti (Chelsea), Alex Stepney (Manchester United), Jimmy Montgomery (Sunderland) and the young-bloods: Peter Shilton (Leicester City) and Pat Jennings (Tottenham Hotspur). They were all working hard to improve their game and, in so doing, the standard of goalkeeping in England.

Though working in isolation we each devised personal training schedules to improve positioning, angles, reflexes, distribution, collecting, punching, dead-ball kicks, dealing with corners and free-kicks, organising the defence and so on. At the time the greatest exponent and the man who can be credited with turning the art of goalkeeping into a science was Banks, widely accepted as the best goalkeeper there has ever been.

You will have heard the phrase, ‘the goalkeepers’ union’. There is, of course, no union as such; it is simply a phrase to explain the bond goalkeepers enjoy with one another. As a specialist position it demands specific skills and attributes, but it also applies pressures that no other position in the team carries. An outfield player can make mistakes and get away with them; he can make a wayward pass and teammates will, more often than not, rectify his error as play unfolds. Not so with a goalkeeper. Mistakes here invariably result in a goal for the opposition. It is the knowledge and pressure of this that invokes in goalkeepers a common bond, and even in the days before teams were requested to shake hands prior to a game, goalkeepers always shook hands when they passed one another after the ritual tossing of the coin before a match.

When the teams met for a drink after a game I always made a point of chatting to the opposing goalkeeper. Quite often he would reveal a little nugget about a player he had encountered and I would try and reciprocate, hence my chat to Banksy about George Best.

Indecision in a goalkeeper gives away more goals than any other flaw, so I always tried to let my defenders know exactly where I was and what I wanted them to do. Nowhere is indecision more catastrophic than in a one-on-one. Quite often a striker is through before the danger can be seen. Call it intuition or instinct, but a goalkeeper must see the opening before a forward and, without hesitation, sprint out to cut down the angle and force the forward wide. It is all about alertness, anticipation and the ability to read a game.

‘You know, as well as I do, what to do in a one-on-one,’ said Banksy, ‘but Best is so quick and skilful, you need a special strategy. Anticipation is the key. You have to be out there, your position and angle spot on when he sets off, because he’s so quick. He’ll weigh you up in an instant, and his ability to change pace and direction is phenomenal. So get out to him as quickly as you can. Stay on your feet and make sure you force him wide to his left. He’s good with both feet, but prefers his right, so get him so the ball is on his left. Jockey him. He’ll twist and turn, but stay on your feet. Just keep jockeying him across to his left, boss it. Eventually he’ll try and switch and give you a glimpse of the ball, and that’s when you go down to collect.’

I thanked Bansky for his advice. It was more or less what I had figured, but hearing it from him made me believe my strategy would be the right one.

Just over an hour into our game against Manchester United at Bramall Lane, Pat Crerand played the defence-splitting ball Banksy had warned me about. George was on it in a flash, but I had taken to my toes a split second before.

George bore down on me. I had taken a position in the left-hand channel of my area, halfway between the penalty spot and the edge of the penalty area, a very good position. I made a half-turn to my right, inviting George across my penalty area. He immediately swerved away to his left, the way I wanted him to go. Excellent. No sooner had he done this than, in more or less the same movement he veered back to his right. I instantly re-adjusted my position. Staying on my feet, I angled my body to force George back onto his left. Got him! I had him switching the ball back onto his left foot, George nudged the ball some nine inches away from his left boot – just what I wanted him to do. I seized my opportunity, went to ground and made a lunge for the ball. I grasped fresh air. In the split second it took for me to hit the deck George switched his right leg across, dragged the ball back with the sole of his right boot, then, with the toe of the same boot, flicked the ball away to his right and my left. Anxious to regain my feet and catch him, I over-balanced and fell backwards onto my backside. Instinctively I stuck out my left arm, but George was gone. I turned in time to see him behind me, in more space than Captain Kirk ever enjoyed. I watched helplessly as he side-footed the ball into the empty net courtesy of his favoured right foot.

George raised one arm in the air and smiled benignly as he walked slowly back towards his rejoicing teammates.

‘Bloody hell, George. You gave me spiral blood,’ I said as he passed me.

‘Ah, you had me going there, Hodgey,’ he replied. A smile as wide as a slice of melon broke across his face. ‘Had a bitta luck.’

Luck didn’t come into it. It was brilliant play on his part. No other player had ever turned me over in a one-on-one with such consummate ease as George did that day. What’s more, no player ever did again.

A couple of months later, I fell into conversation with Banksy after we had played Stoke City at Bramall Lane. During our chat I recalled my experience with George.

‘Did just as you said. To the letter,’ I informed Banksy. ‘Forced him across goal and onto his left foot. Stayed on my feet, forced him further to his left till he gave me a glimpse of the ball. He dumped me on my arse and tapped the ball in the net. Made me look a right Charlie.’

Bansky rubbed his chin with the thumb and forefinger of his right hand.

‘Yeah, thought he would,’ said Banksy, emitting a sigh, ‘he did exactly the same to me.’

* * *

George Best was a football genius and, sadly, there is no true genius without a tincture of madness. I have nothing but fond memories of George and, as I will also later recall, found him to be a very intelligent, immensely witty, amiable and caring guy who, for all his fame and exploits, was surprisingly shy.

I have now reached an age where I increasingly find myself recalling the great players, great games and even the not-so-great names and games that provided the essence to my sixty-year career in professional football. I am, if nothing else, a very lucky guy indeed. To have enjoyed – and I emphasise the word ‘enjoyed’ – sixty years as a player and coach in professional football, is a journey I could never, in my wildest dreams, have envisaged making when I first signed for Sheffield United back in the days when the only thing that came ready to serve were tennis balls, and it was girls that brought me out in a sweat and not tandoori chicken.

Football has been my life and it has blessed me with a treasure trove of memories. Memory tempers prosperity, mitigates adversity, controls youth and, as I am now discovering, delights one in the seasoned years. The true art of memory is the art of attention. During the course of their careers many players never take note or commit to memory the characters, games, unguarded asides, humour, friendships, golden moments and angst they experience – quintessentially what makes football so entertaining and the greatest team game on the planet. I had the presence of mind to document my career: I kept and logged every press report of every game I was ever involved in, from my salad days as a teenage amateur with Worksop Town via Sheffield United and England, to my role as a coach with myriad top clubs and both Scotland and England.

I also kept the match programmes of every game I was involved in. These and my personal collection of scrapbooks and notebooks have proved to be invaluable now that I have decided to commit my story to paper. I have never written a book before but, after sixty years of continuous employment in the game, I felt the time was right.

During the course of my career I have seen football change irrevocably, from a working man’s leisure pursuit to the multi-billion-pound industry that it is today. Self-appraisal is no guarantee of merit, I know, but rather than being one of those former players who believe football past was far better than football present, I would like to believe I have not only moved with the times but, in my field of goalkeeping, have always been an innovator. In recent years the ideas I introduced to my UEFA coaching sessions attended by the likes of José Mourinho, Harry Redknapp, Rafael Benitez and Felipe Scolari have, I would like to think, in some small way enhanced their expertise as coaches in the modern game. Football past was great, but so too is football present. That I have continued to contribute in a positive way to the game I love so much is a constant source of joy to me.

Though now in my eighth decade, I do not feel old. On the contrary, the fact I have continued to work in the game has kept me young of mind and heart. A friend once said to me, ‘How old would you put yourself at, if you didn’t know how old you were?’ It’s a good question. Thanks to my long career in football I would put myself at an age far younger than my actual years. That is just one of the great gifts and benefits football has given me and one of the reasons why I am so grateful to the game that has, and always will have, a special place in the best of all possible worlds.

* * *

I was born on 16 August 1936. Little over two weeks later King Edward VIII abdicated, Nazi troops occupied the Rhineland and civil war broke out in Spain. An unfortunate sequence of events, but I have it on good authority that none of these was due to me having entered the world.

I was born into a hard-working and principled working-class family. My dad, Len, was a loving father, though something of a stickler for discipline. He was also an enigma in our home town of Laughton Common, which is equidistant between Sheffield and Rotherham, being as he was a miner at Dinnington Colliery and also an accomplished concert pianist.

When it comes to playing the piano some people can carry a tune but appear to stagger under the load. Not so Dad. Those strong, gnarled hands that hewed coal for eight hours on a daily basis would suddenly be transformed into deftly gliding fingers that lovingly caressed the piano keys. So popular was he as a pianist that Dad often gave recitals at civic halls and theatres throughout South Yorkshire and, in the summer, entertained holidaymakers at Butlin’s holiday camps. I would listen to him play and be totally transfixed. He not only reproduced the piece perfectly but he seemed to capture its very essence and that of its composer.

Given his talent, I have often wondered whether if he had been born into a middle-class family in, say, the leafy suburbs of Betjeman’s London rather than a working-class family in the South Yorkshire coalfields, his musical destiny would have been different. Dad was born at the turn of the twentieth century, when working people accepted their lot. There was little, if any, recognition of a working person’s musical talent by the great and good of classical music. Dad would never have had the wherewithal nor was he offered the opportunity to develop his talent at a musical college or academy. A great pity, not least because a bill poster proclaiming, ‘The Conservatoire Collier plays Chopin’, would have had a wonderful alliterative ring to it.

Dad began working down the pit at the age of fourteen and continued to do so until he retired at the age of sixty-five. He hadn’t missed a day’s work and, what’s more, in fifty-one years as a miner Dad was never once late. On his retirement, the well-meaning folk at the colliery bought him a clock.

My mum was called Ivy. She was a very loving and attentive mother who, in keeping with most mothers of that era, worked impossibly long hours cooking, washing, ironing, cleaning, mending and shopping for her family. Long before the phrase was invented, women were ‘multi-taskers’, quite simply because their role of looking after the home and children and everything to do with domesticity was labour intensive.

I was fortunate in having a mother and father who took an interest in me, my brothers and sister. I felt Dad knew me and what made me tick. Most of the other dads I knew were also miners but they spent little time with their kids. In the 1940s, as now, a mother knew everything about her children – the scabs, nits, bad teeth, best friends, favourite foods, constipation, shoes that didn’t fit properly, romances, secret fears, hopes and dreams – but most fathers were only vaguely aware of the small people living in the house. Not so my dad.

Home was a two-up-two-down red-brick terraced house on Station Road in Laughton Common. People stayed in their jobs in those days and they stayed in their houses too. It was unheard of for couples to set up home before they were married. Once they had, the vast majority stayed put until the time came for their children to call the funeral director. There were no nursing homes, no managed flats for the elderly. A house was bought or rented and turned into a home by women like my mum. At various times it was also a nursery (though no one ever used the term ‘nursery’ in the 1940s), a hospital, classroom, party function room, music hall stage, a rest home and, in the vast majority of cases, in the end, a chapel of rest for those who had purchased the house in the first place.

Internally and externally, the houses took on the character of their occupants. From either end of Station Road the terraced houses all looked the same, but as a boy I soon learned the subtle individualities of each one. It was the small touches – invariably the mother’s – that gave them their identity. The highly polished brass letterbox on the front door of the Coopers’; the pristine gold-leaf house number on the fanlight over the front door of the Cartwrights’ (as a boy I had no idea why this number had survived intact when all the others had become mottled and flaked with age); the net curtains in the front window of the Thompsons’, gathered rather than hanging straight as in every other home; the red glass vase, no more than four inches high, that balanced precariously on the narrow window ledge in the Smiths’ front window.

Those surnames were all traditional, straightforward, dependable, no-nonsense names, most of which owed their origin to some trade or other. When I was a boy it was said Sheffield boasted more Smiths than anywhere else in England, until, as Dad once joked, the title was taken one weekend by a cheap hotel in Brighton.

Fresh flowers were a rarity in the houses. In the summer, Mum would occasionally give me a threepenny bit (just over 1p) and send me across to the allotments which were, in the main, rented by miners. I would ask the allotment owner, ‘Have you any chrysanths you don’t want?’ Chrysanths – that was all the miners who ran the allotments seemed to grow in the way of flowers. With their football-like blooms (there was even a species called ‘Football Mums’) and tall stems, these flowers dominated the small living rooms of the houses they fleetingly graced.

Keen to make threepence and offload my surplus flowers, I would find myself skipping home with an enormous bunch of earwig-infested chrysanths. Mum would indeed marvel at them before cutting their stems and displaying them in two or often three vases around the house. I only realised their full name, chrysanthemums, when I was in my mid-teens. True, chrysanths runs off the tongue a lot easier but, looking back, there might have been another reason for the shortened name. Chrysanthemum sounds Latin, something only posh kids learned. In Sheffield and Rotherham in the forties such class distinction was as clearly drawn by the working class as it was by the middle and upper classes, and you wouldn’t want to be accused of getting above your station.

Mum organised the house and family life and we functioned to a tried-and-tested routine. We had no bathroom; we washed twice daily at the kitchen sink, usually with cold water. In keeping with every family I knew, Friday night was bath night. Dad would take down the tin bath from its hook in the backyard shed. It would be placed on newspaper in front of the living-room fire and laboriously filled by Dad with kettles of hot water. First to go was Dad, then my sister, followed by my two brothers, then me. Being the fifth user of the same bath water it’s a wonder I didn’t get out dirtier than when I got in.

It seems unbelievable now, but Friday night was the only time in the week when I changed my underpants and vest. Again, we were not unique in this, every family I knew changed underwear weekly. There were no modern labour-saving devices such as washing machines. Mum washed our clothes every Monday, in the kitchen, with a tub and dolly, after which she would hand-rinse everything then put all the washing through a hand-operated wringer before hanging it out to dry, or, in the event of rain, on wooden clothes horses which were dotted around the living room or placed in front of the ‘range’ fire. Come Tuesday they were dry. On Wednesday they were ironed and then put away in wooden drawers that smelled of lavender and mothballs, ready for us to wear again on Friday after our bath, and so the cycle was repeated. Mum’s life must have been as monotonous as mutton, as regular as the roll of an army drum. That my childhood was such a happy one, secure and filled with a warm heart is to her eternal credit.

Saturday was football day, but for the vast majority of Laughton Common women and, I would suggest, women everywhere, it was the day they had their hair done. It was the time of ‘Twink’ perms for women and an entirely different type of perm for the menfolk.

Come the weekend, the women of Laughton Common would buy a Twink perm in their quest to have glamorous hair, if only for a couple of days. I recall my mother and neighbouring women spending most of Saturday with myriad purple plastic grips in their hair which to me looked like small chicken bones. Around these purple ‘bones’ they wrapped strands of hair and tissue paper. I never knew the reason for the tissue paper and still don’t; it was minutiae from a mysterious female world that, for all it touched mine, was to remain beyond my ken.