Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

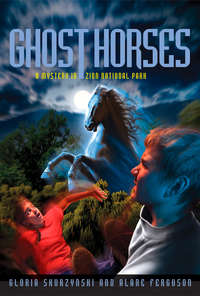

Kitabı oku: «Mysteries In Our National Parks: Ghost Horses: A Mystery in Zion National Park»

Ghost Horses

GLORIA SKURZYNSKI AND ALANE FERGUSON

Text copyright © 2000

Gloria Skurzynski and Alane Ferguson

All rights reserved.

Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents is prohibited without written permission from the National Geographic Society, 1145 17th Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036.

Cover illustration and design by Matthew Frey, Wood Ronsaville Harlin, Inc.

Photo insert credits: Indian dancer, James Amos; wild mustangs,

© John Eastcott/Yva Momatiuk; water trap, courtesy Bureau of Land Management; Angels Landing, Jamal D. Green; The Narrows, Frank Jensen

Endsheet maps by Carl Mehler, Director of Maps; Thomas L. Gray, Gregory Ugiansky, and Martin S. Walz, Map Research and Production

Running horse art by Stuart Armstrong

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to living persons or events other than descriptions of natural phenomena is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Catalog Number 00-027730

ISBN: 978-1-4263-0969-4

Version: 2017-07-07

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank Denny Davies,

Chief Naturalist, Zion National Park;

Donald A. Falvey, Superintendent, Zion National

Park; Tom Haraden, Assistant Chief Naturalist,

Zion National Park; and Gus Warr, Wild Horse

and Burro Specialist at the Cedar City Field

Office, Bureau of Land Management.

Our very special thanks go to our patient

friend and fellow writer Lyman Hafen, Executive

Director of the Zion Natural History Association,

and to Art Tait, Cedar City Field Office Manager,

Bureau of Land Management, who introduced us

to Mariah and who spent so many hours driving

us across the Chloride rangeland to educate

us about wild mustangs.

For Kristin and Matt

We wish you a lifetime of happiness.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Afterword

About the Authors

A rough branch drilled into his chest, like a skeleton’s finger, but the man knew he couldn’t change his position. Even the smallest flicker of movement would let them know he was there, and the man had spent too much time setting the trap to tip them off now. Behind him he heard the rustling of flanks against juniper trees. He held his breath when he saw it—a flash of silvery white, so pale it seemed as if a piece of moon had dropped from the desert sky. A Ghost Horse.

As he watched it move closer to his trap, the man tried not to think of the strange stories he’d heard, tales of white horses that whinnied a language of their own, caught between this world and the next. The mustang, ghostly white, stepped inside the trap. The man leaped out of the blind and slammed the gate shut. He had his prize.

Again and again the mustang hurled itself against the rails, rearing up before slamming into them in an explosion of sound. It gave a strange, ghostly cry that echoed back from the hills. Then he heard the pounding of hoofs. Frightened, the man turned and ran.

CHAPTER ONE

War cries cut the air in quick, high-pitched bursts until Jack’s ears rang with the sound. In front of him, 200 Native Americans from dozens of tribes danced through the arena, some with spears in their hands, others clutching eagle feathers as they swirled and pulsated in a dizzying, rainbow-hued parade. Jack had never before been to a powwow. He wished he could go out there and dance to the pounding of the drums instead of just sitting with his sister, Ashley, on hard bleachers.

“Isn’t this great, Jack?” Ashley enthused.

“Yeah. Great.” He meant it. It just wasn’t cool to sound as gushy as his sister.

There was so much motion and color that Jack had to keep switching his gaze, from the gate where more and more dancers swept in, to the far side of the grounds, where horses pawed and snorted, held in check by wildly dressed warriors. The Indian riders looked strong and fierce, with their faces painted and their headdresses bristling with feathers that made them seem larger than life. One carried a yellow shield decorated with buffalo images and red feathers. Another, wearing a black vest and beaded armbands, swung a war club above his head; yet another raised a spear as he galloped his horse in tight circles. How would it feel, Jack wondered, to be a part of something that had been passed down from one generation to another, so far back that no one could remember where it began? To know about your ancestors—unlike Jack, who didn’t even know the name of his own grandfather.

“Can you see Ethan or Summer?” Ashley asked, straining to catch a glimpse of their new foster children in the crowd of dancers.

“Right over there. On the other side of the circle, by the sign that says Eastern Shoshone Indian Days.”

Shading her eyes, his sister strained to see. With her own dark hair braided into long ropes and her end-of-summer tan, Ashley could have fit right in with the rest of the dancers. Jack, whose hair was blond and straight like his father’s, felt a little bit out of place, since there were almost no other Anglos sitting close by.

“I still don’t see them,” Ashley pressed. “Where are they?”

“Ethan’s next to the chief with the humongous headdress. Summer’s in the middle of the circle next to the lady in the buckskin. See where Dad’s standing underneath the sign taking pictures?” Jack pointed. “They just went past him.”

“Oh, yeah,” Ashley nodded. “There they are. Wow, Ethan’s dancing like crazy. Look at him go!”

Dressed in a bright blue vest and chaps edged with an eight-inch fringe, Ethan Ingawanup whirled in circles so fast that the fringe stood straight out from his body. A wheel of feathers three-quarters as tall as Ethan was attached to his back, like a fanned-out peacock’s tail. His feet moved as though they had a life of their own, furiously beating against the dirt so that it churned up in tiny puffs. Twenty-three different tribes were taking part in the Shoshone Indian Days celebration, all dressed in ceremonial regalia. Each footfall of the dancers hit the ground like a hammer blow timed to the beat of the drums. One dancer, half his face painted in a white mask, spun in front of Jack. The bronze skin of his naked torso rippled with muscle as he moved close to the earth before reaching for the sky, up and down, like a bird soaring and diving through the air.

Summer, Ethan’s younger sister, danced in the inner circle. Her dress was encrusted with silvery, cone-shaped jingle bells that made a tinkling sound as she moved in tiny, mincing steps.

“I’d like to dance like that,” Ashley said. “But I’d rather do the dance Ethan is doing, because Summer’s hardly moving. Wouldn’t you like to learn that warrior dance?”

“Maybe. Yeah, I guess.”

“Do you think Ethan would teach us?”

“I doubt it,” Jack muttered.

Ashley’s dark eyebrows edged up her forehead as she asked, “What’s your problem, Jack? You’re acting like you don’t like Ethan.”

Jack just shrugged. He didn’t want to get into it with his sister, even though he knew her well enough to figure she wouldn’t drop the subject. He took a swig of Coke from his can and tried to get back into the spell of the dancing, until he felt a tug on his arm.

“You ought to try, you know. Liking him, I mean.” Ashley moved closer to Jack on the bleacher, so that the toe of her tennis shoe pushed against his. “There’s lots we could do together with them, especially since Ethan’s your age and Summer’s mine, instead of the other way around. It’s perfect.”

Coolly, Jack studied his ten-year-old sister. He’d always found it a bit hard to deal with the foster kids who spun in and out of their lives like shoppers flung out of a revolving door. “Emergency care” kids, that’s what they were called—children who needed sheltering for a short time. Ashley enjoyed them more than Jack did, but he’d managed to make it work somehow. He’d pretty much decided he could get along with anyone, until that morning when they’d picked up the two newest foster kids from Indian Child Welfare. They were different.

Summer, a ten-year-old Shoshone girl, had been as quiet as a ghost, watching their every move with a sad moon face that never changed expression. If they were only supposed to take care of Summer, Jack wouldn’t have worried. It was her brother, Ethan, 12 going on 13, Jack didn’t know what to make of. From the moment they’d met, Jack had noticed the anger flashing behind Ethan’s dark eyes, the way he’d stared at Jack as if he were the enemy. Even though they’d been together only a couple of hours, it was enough for Jack to make his own conclusion: Ethan was going to be trouble.

“Look—if you want Ethan to teach you to dance, then ask him yourself,” Jack said, taking a fierce bite of his Indian fry bread. “I plan to stay out of his way.”

Ashley crossed her thin arms over her Indian Days T-shirt. “Oh, great, Jack. go on, act like a toad.”

“Hey, Ethan’s the one, not me.”

“At least he’s got a reason,” Ashley said, boring her eyes into his. “How’d you like it if you were Summer or Ethan?” Inside, Jack groaned as Ashley held up her hand and ticked points off on her fingertips. “First”—her index finger went up—“their parents die in a car crash. Then”—her middle finger shot into the air—“the grandmother who raised them gets put in a nursing home. Now”—Ashley finished with her ring finger—“they’ve got to leave their reservation and go off with strangers—you and me, Mom and Dad—who they never even met before today.”

“I know all that,” Jack snapped. “I’m just saying there’s something really weird about that Ethan.”

“Like what?”

“Like, I don’t know—lots of things. When we were waiting in the lobby at Social Services, I gave him a piece of gum. You know what he did with it?”

Ashley shook her head, causing her braids to bounce against her back like black ropes.

“He threw it in the garbage. He didn’t chew it, didn’t even open it—he just dumped it. Then he looked right at me, like he was daring me or something.”

“Maybe he doesn’t like gum.”

“That’s not it.” Jack raised his voice to be heard over the beat of a nearby drum. “He’s got some kind of attitude, you know? And the worst part is that we’re stuck taking them to Zion National Park with us tomorrow. They could ruin our trip, which really ticks me off. Especially since Dad and I are going on a great photo shoot in The Narrows, just him and me. There’s no way I’m gonna let that get ruined. I wish we’d never gotten Ethan.”

“That’s dumb. How could he ruin your trip?”

“Who knows? Anything can get screwed up when you’re dealing with a punk like him.”

“The key to Ethan and Summer,” a voice from behind them broke in, “is time. You just need to give them time.” When Jack whirled around, he saw Vivian Swallow, the social worker who had placed Ethan and Summer in the Landons’ care.

Jack could feel the heat rush to his cheeks. Caught! Caught mouthing off. If Vivian Swallow told Jack’s mother and dad what he’d just said, he’d be in real, heavy-duty, industrial-size, no-way-out trouble. “I…I didn’t…,” he stammered.

“It’s OK, Jack,” Vivian said, placing a hand on his shoulder. Right away Jack knew this woman wouldn’t tell. She was as warm and forgiving as Ethan was cold and hostile.

Half Shoshone, Vivian had high cheekbones, wide-set eyes flecked with green, and hair streaked with honey-colored strands. She’d dressed up for the powwow in an elkhide sheath beaded with brilliant Indian patterns. Two long fur pelts were attached to the ends of her braids; they hung down below her knees. Leather moccasins made her footsteps so soft that Jack hadn’t heard her coming up next to them.

“I see your dad over there, but where’s your mother?” Vivian asked.

“She’s standing in line waiting for the food,” Ashley answered.

Vivian turned to Jack. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but I couldn’t help overhearing what you said about the Ingawanup kids. Is it OK if I sit here with you two?”

“Sure, I guess,” Jack told her, scooting away from Ashley to make room. His cheeks still felt hot from embarrassment.

Vivian turned to Jack, her large eyes resting on his. “So you’re not real happy about Ethan. No, it’s OK.” She stopped Jack as he began to apologize.

“Jack thinks Ethan’s mean. Is he?” Ashley asked.

Vivian smiled, revealing perfect white teeth. “I like how you get right to the point, Ashley. Maybe Ethan might be, well, just a little less than friendly. Let me explain.” Flipping the long fur braid decorations behind her back, Vivian looked from Jack to Ashley, then back to Jack. “Here on the Wind River Reservation, most people watch out for their own. Families take care of families. But unfortunately, right now there’s no one who can offer a home to Ethan and Summer. Which means I had to place them outside the reservation. Those two are leaving the only life they’ve ever known, and that’s tough.”

“What about their sister?” Ashley asked. “Mom said there was a big sister who’s going to be their guardian.”

“That’s right, but Tamara won’t be back for five more weeks. She wants to finish out her college semester before returning to Wind River.”

Ashley pressed, “You still didn’t say why he doesn’t like us.”

“Well, it could be because there’s been…trouble…between Ethan and some of the town boys outside our reservation.”

“You mean Ethan fought with the white kids?”

Vivian nodded and patted Ashley on the knee. “You’re a smart one, aren’t you?”

“So Ethan thinks we’re like them, right? Like the kids who fought him.”

“Maybe.” Vivian nodded again, this time more slowly.

Jack leaned forward so that he could see Vivian’s face better. “But, I don’t get it. If Ethan doesn’t like Anglos, then why did you put him with us? I mean, isn’t that the worst thing you could do?”

“Two reasons. First of all, right now there’s no one else. I was going to try to pull a lot of strings to keep them at Wind River, but then I hit on the second reason.”

“What’s that?” Jack asked.

“Well, I figured putting Ethan with kids—good kids like you and your sister—might help him more than anything else.”

The music stopped and the dancers began to scatter, like bright leaves in the wind. Vivian looked off into the distance. Her voice softened as she added, “Ethan needs to see people as people. Maybe we all do.” Straightening, she said, “Well, looks like the food line’s starting to move. Let’s get over there with your mother. Has either one of you ever tasted buffalo before?”

“Never,” Jack answered as Ashley cried, “No way! Is that what they’re giving us to eat? Buffalo? Yuck!”

“Really, it’s great!” A tiny smile bent the corners of Vivian’s mouth. “Looks like Ethan and Summer aren’t the only two who’ll be experiencing something new!”

CHAPTER TWO

When they left the powwow, the sun was still high above the horizon, a pale yellow disk against a flat, washed-out sky. As Jack looked through their car window, the reservation land appeared bleached. All around him, small buildings the color of sand blended into grassless hills that disappeared into nothing. After all the color of the dances, the area beyond the powwow seemed to have dried up and faded.

“Aren’t you going the wrong way, Dad?” Jack asked when he realized his father had left the main highway and was now heading north on a dusty ribbon of road.

“We can make it from Wind River to Jackson Hole in”—his father, Steven, glanced at his watch—“two hours, which means we can stop at Sacagawea’s grave and still get home with plenty of time to pack for our big trip to Zion.” Looking at Ethan’s reflection in the rearview mirror, he said, “You have an advantage on us, Ethan, since your suitcase is already loaded up. We Landons still have to get our act together.”

Silence.

“So, have you ever been on an airplane?”

Ethan pressed his forehead into the glass and said nothing. His long hair covered his face like a waterfall, shutting them out.

“How about you, Summer?” Steven asked, his voice still jovial.

Summer just shook her head no.

Great, Jack told himself. He could see it now—an entire vacation filled with his parents fussing over Ethan and Summer while the two of them sat like stone. Sighing, he read a road sign, a small rectangle that looked as unassuming as a tag at a rummage sale. It pointed to the cemetery. A moment later they pulled into the tiny parking strip.

As Jack got out of their Jeep, he thought how Vivian Swallow had been both right and wrong. She’d been right about the feast: The roast buffalo tasted wonderful. It was a lean, tender meat without a gamey flavor. Even Ashley liked it. Of course, she’d also piled her plate high with sweet corn and ripe watermelon and beans and salad and a dessert that looked like a cherry cobbler. The feast had definitely been worth staying for.

But Vivian had been dead wrong about Ethan. He hadn’t said a word—not during the feast, not when they’d said good-bye to Vivian, not when Jack’s mother, Olivia, told him how happy she was to be taking the Ingawanup kids to Zion, not even when Jack’s father, Steven, tried to draw him out by telling him about the years he’d spent as a foster child himself. No matter what the Landons tried, nothing worked. Ethan answered everything with a stony silence, as if the only thing that would make him and his sister happy would be to have the Landons disappear.

Now Steven and Olivia hung back beside the Jeep, their heads close together as they spoke in low voices—talking about Ethan and Summer, Jack figured. His father kept rubbing the back of his neck with his hand, a sure sign that he was worried.

Jack felt awkward just standing there at the cemetery entrance, so he finally called out, “Come on, Mom and Dad, what are you waiting for? Let’s go.”

“Why don’t you kids go on ahead?” his mother answered. “Your father and I need to talk for a minute.” Wisps of dark, curly hair escaped from underneath a baseball cap Olivia had pulled low on her forehead. She often wore T-shirts with pictures of animals on them. Today, she had on a green shirt with the footprints of different extinct species scattered across it.

“Go on, son,” Steven told Jack. “Ask Ethan and Summer to show you the Sacagawea monument. We’ll join you in a bit.”

Great, just great, Jack fumed. Well, the faster he went, the faster he could get this whole thing over with. “Summer, do you know where the grave is?”

She looked up at him, her dark eyes wide. Jeez, she can’t even answer a simple question, Jack thought.

“I’ll take you.” Spinning on the tips of his running shoes, Ethan led the way. Now that Ethan was out of his dancing regalia and in a white T-shirt and jeans, Jack could tell how compact yet strong he really was. His arms moved loosely at his sides as he hurried up the hill, so fast Jack and Ashley had to scramble to keep up. As he moved, shoulder-length black hair flew off his face, revealing a strong jaw set in a hard line. Although Summer looked delicate in her yellow-flowered sundress, she had enough energy to follow her brother with no apparent problem.

“Slow down,” Ashley called out, but Ethan kept moving at top speed up the narrow path. Determined not to let them beat him, Jack began to jog up the incline, leaving his sister to tag behind. Gravestones dotted the wild grass like scattered teeth, some of them tipped to one side, others with the surface worn to a smooth polish, the letters rubbed bare. Many of the markers were simple slabs of wood. Although some seemed neglected, most of the graves were adorned with bright plastic flowers in every color of the rainbow, as though someone had scattered a giant bag of candy across the barren ground. It was a wind-blown, dusty place. Hardly what he expected to see as the final resting place of someone as famous as Sacagawea.

Ethan and Summer had stopped in front of the largest tombstone. More plastic flowers adorned the grave, along with nickels, dimes, and quarters that had been pressed into the baked earth. The coins caught the sunlight and threw it back like tiny mirrors.

Casting a wide shadow, the large rectangle of granite showed the probable dates of Sacagawea’s birth and death, along with a bronze plaque that detailed her life.

“Thanks for waiting, Jack,” Ashley panted when she joined him.

“Sorry.”

“It’s OK. Wow, here it is. I’ve heard so much about her, how she was the guide for the Lewis and Clark expedition even though she was really young. I can’t believe I’m standing right at Sacagawea’s grave.” Ashley took a breath and added, “She was a Shoshone too, right?”

“Yes. But she’s not buried here,” Summer answered in a small voice. “Sacagawea died in the mountains. No one knows where her body lies. They made this to honor her.”

Ashley shot Jack a triumphant look that seemed to say, “See, she talks!” Placing her hand on Summer’s arm, Ashley said eagerly, “I think Sacagawea was a real hero.”

“To you,” Ethan said sharply. “Not to me. Not to my sister.”

Jack and Ashley looked at Ethan in surprise. “Why don’t you think she was great?” Ashley asked.

Ethan’s thick brows knit together. “She helped the white man, and the white man took all our land. My grandmother said Sacagawea should not have helped anyone but her own people.”

Nodding, Ashley tried to get him to keep talking. “I bet your grandmother taught you a lot of things, didn’t she?”

“Yes. She taught us the old ways,” Summer answered for him. “She taught us the traditional way to dress. She taught us how to cook and hunt and even how to dance, like we did today.”

Ashley beamed, triumphant over the fact that Ethan and Summer Ingawanup were finally opening up. “Do you think sometime, maybe later, you could teach Jack and me how to dance like that? I’d really like to learn.”

Ethan snickered loudly. His eyes rolled to the sky as he muttered, “I’m not teaching no white guys.”

That did it. Jack felt irritation surge through him. “Look, Ethan, whether you like it or not, the four of us are stuck together. Do you think it would kill you to stop being a jerk for a couple of weeks?”

“Jack—don’t—” Ashley began, but Jack didn’t care. He moved right in front of Ethan, staring him down, eye to eye. “You know, we didn’t ask for you to stay with us, but you’re here with our family. So why don’t you give up the attitude, OK? Then maybe we can get through this until your big sister comes back, and then you can go home and forget about us white people.”

Ethan stood with his legs spread apart, his arms crossed over his chest, his eyes hard. Wind began to blow over the hill, bending the grass toward the ground like stalks of wheat, moving Summer’s hair in dark wisps across her face. Jack wasn’t about to back down, and neither, it seemed, was Ethan. Finally, like clouds parting, Ethan’s face cleared. With what looked almost like a smile, he said, “OK.”

Nothing Ethan could have said would have taken Jack more by surprise. “OK…what?” he asked, still not believing Ethan’s turnaround.

“OK, I’ll try to be friends.” Smiling slyly, he said, “So you want to learn how to dance?”

“Sure,” Ashley answered, nodding eagerly.

“Then I’ll teach you. I’ll teach you and your brother the Ghost Dance.”

Summer pushed the hair off her face, saying, “No, Ethan—”

“Yes. It’s a good dance, very old. Gotta be danced around a cedar tree.” Ethan looked completely different when he smiled. His teeth were white and square in his dark face, but the smile didn’t make it all the way up to his eyes—they still glittered coldly. “Don’t worry,” he told them. “You’ll like the Ghost Dance.” Without another word Ethan spun around and began running through the gravestones, higher and higher in the cemetery grounds until he veered off at the top of the hill. Summer followed him, glancing nervously over her shoulder as she went.

“I guess we’re supposed to go after them,” Ashley said.

“Except there’s no way I’m going to dance. Not here. Not with Ethan.”

Ashley’s voice rose half an octave. “What do you mean? We can’t tell Ethan ‘no’ when he’s finally trying to be nice. You’ve got to.”

“You dance. I’ll watch.”

“No way!” Grabbing the edge of his sleeve, Ashley tugged hard. “Please!” she begged. “Maybe it’ll make us all friends! Besides, at the powwow you said you wished you could dance like them.”

“That’s not the same thing. They had costumes and drums. Out here I feel stupid!”

“No one will see! Besides, our whole trip to Zion will be ruined if we don’t get along with them.”

That much was true. He looked around the cemetery. His parents, still talking, were finally making their way up to Sacagawea’s marker, but beyond them the grounds were completely empty. Jack heaved a sigh. “OK. But if any stranger shows up, I quit. And let go of my sleeve. You’re stretching my shirt.”

As they climbed toward the Ingawanups, Jack noticed that Ethan seemed to be searching for something. After a few minutes he began kicking rocks away from the ground around a small green tree that stood no more than two feet high.

“Hey, watch where you’re kicking those things,” Jack yelled. “One of them nearly hit my sister.”

Summer murmured, “Ethan, maybe we shouldn’t do the Ghost Dance…”

Her brother ignored her. “I just needed to clear some space around this cedar tree. I told you that’s what we’re supposed to dance around—a cedar tree.” Impatiently, he gestured for Jack and Ashley to come closer. “Go ahead,” he told Summer, who asked him, “You sure, Ethan?”

When Ethan nodded, Summer said in her soft voice, “Stand around the tree. Boy, girl, boy, girl. Take hands.” Jack grasped Summer’s hand as if in a handshake, but she shook her head and said, “No, like this,” and twined thin fingers through his.

Since there were only four of them, the circle was small—Summer, Jack, Ashley, Ethan. His voice low, Ethan began to sing:

I’yehe’ Uhi’yeye’heye’

I’yehe’ ha’dawu’hana’ Eye’de’yuhe’yu!

Ni’athu’-a-u’ a’haka’nith’ii

Ahe’yuhe’yu!

Tugging Jack’s hand, Summer moved in a circle from right to left, left foot first, followed by the right one, barely lifting her feet above the ground as they moved. Awkwardly, Jack stumbled along; on his other side, Ashley had caught the motion perfectly and danced as though she’d always done it that way. Ethan’s voice grew louder, pounding each note like a beat on a tom-tom. Jack guessed he was singing the same song over and over, although the words sounded so strange that Jack couldn’t tell whether they were being repeated or not.

He glanced down the hill to the Sacagawea monument, where his mother and father stood looking up at the kids and smiling, probably thinking how sweet it was that the four of them were doing a little circle dance together. Probably figuring that everything was all right now. But was it?

His attention was jerked back to the dance, because Ethan had stopped his chant and Summer began to speak. Her voice soft, her eyes half shut, she murmured, “Grandmother’s grandmother saw the big fire on the mountaintop. Our people were dancing the Ghost Dance. They danced. They danced. The fire burned higher.” Summer spoke in a monotone, her voice neither rising nor falling, but for some reason it made Jack’s scalp prickle.

“Grandmother’s grandmother saw the smoke. It rolled down the mountain. It covered the earth and the people and the animals. No one could see, but they kept dancing. The smoke got thicker. It hid the sky. It hid the earth. It hid the horses, and turned them into ghosts.”

Now Summer spoke in a singsong. “After two days the smoke was gone. After two days the horses were gone. They became ghost horses. But sometimes, when the people danced, the ghost horses returned.”

While she told the tale, Summer’s eyelids drooped lower and lower, while Ashley’s eyes widened until the whites showed. As for Jack, he caught the smell of—no, that was crazy. He couldn’t be smelling smoke—there wasn’t a wisp of it showing anywhere, nothing rising into the perfect blue sky, and from that high on the hill he could see all around. Then Ethan began to sing once more, louder than before,

I’yehe’ Uhi’yeye’heye’

I’yehe’ ha’dawu’hana’ Eye’de’yuhe’yu!

Ni’athu’-a-u’ a’haka’nith’ii

Ahe’yuhe’yu!

By that time, Steven and Olivia had climbed closer to where the kids danced around the little cedar tree. They were still 20 feet away when Ethan stopped abruptly and pulled his hands away from Ashley’s and Summer’s.

“Oh, don’t stop,” Olivia begged. “That was just—charming.”

Ethan turned into stone man again. He didn’t say a word.

“I loved it!” Ashley exclaimed. “Can we do it again? Maybe when we get to Zion National Park? Ethan says we need a cedar tree; I bet there’s lots of cedars in Zion. You’ll do it again, too, won’t you, Jack?”

Jack didn’t know whether he wanted to dance the Ghost Dance again. It made him feel off balance, and not just because of the strange rhythmic words that he couldn’t understand. It was something more, something he couldn’t quite wrap his thoughts around.

But the dance could be a way to keep things smooth between himself and Ethan, and for that reason alone he should agree to do it once more. What did it matter, anyway, if he shuffled around in a circle while Ethan sang, or chanted, or whatever you called it—Jack didn’t know whether the words had any meaning at all.

That part about the horses, though, that Summer told—that part was different. Ghost horses. Ghost horses moving across the empty plains in search of—what? He shivered a little, even though the mid-September sun felt warm on his arms.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.