Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

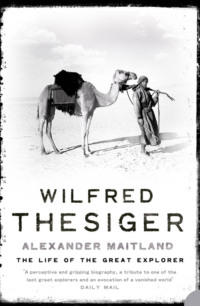

Kitabı oku: «Wilfred Thesiger: The Life of the Great Explorer», sayfa 4

As she read Wilfred Gilbert’s letter aloud, Kathleen must have pictured her husband in his khaki shirt and riding breeches, smoking his pipe in the shade of his fly-tent or under a shady tree; writing with meticulous care on official paper ruffled now and then by the wind; sketching wild animals he described to bring his words alive. His account of shooting a female rhino clearly illustrates the dramatic change in our attitude to wildlife since the days when big game hunting was viewed uncritically (indeed, was strongly justified and admired) as sport. Nor was the episode by any means untypical of hunting adventures at that period. ‘Last night,’ he wrote, ‘two of our soldiers were out at night & they were attacked by an old mummy rhino which had a baby one with her and they had to shoot but they had not many cartridges & did not kill her & then they had to whistle for help & we all took our guns & ran out & daddy shot her and she fell but got up again & we all fired again until she was deaded & then we chased the baby one in the moonlight & tried to catch him but could not as he ran too fast.’42

As a small boy Thesiger was thrilled by stories such as these. As he grew older he memorised tales of lion hunts and of fighting between warlike tribes told by his father’s Consuls. Arnold Wienholt Hodson, a Consul in south-west Abyssinia, hunted big game including elephant, buffalo and lion. Aged six or seven, Thesiger pored over Hodson’s photographs of game he had shot, and listened spellbound to his stories. Later he read Hodson’s books Where Lion Reign, published in 1927, and Seven Years in Southern Abyssinia (1928). Introducing Where Lion Reign, Hodson wrote: ‘In this wild and little-known terrain which it was my mission to explore, lion were plentiful enough to gladden the heart not only of any big game hunter, but of all those whom the call of adventure urges to seek out primitive Nature in her home among the savage and remote places of the earth.’43

By then Wilfred Thesiger was at school in England. As a teenager yearning to return to Abyssinia, his birthplace and his home, he drank in like a potent elixir Hodson’s words, which defined precisely the life he aspired to, the life he was determined one day to achieve.

FIVE Passages to India and England

When war was declared in August 1914, Thesiger’s father was still on leave in England. ‘An accomplished linguist, fluent in French and German,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘he was accepted by the Army, given an appointment as captain in the Intelligence Branch, and sent to France, where he arrived on 23 September. This posting was a remarkable achievement…He was attached to the 3rd Army Corps, and while serving in France he earned a mention in despatches.’1

Wilfred Gilbert’s four-month posting was indeed ‘remarkable’, not only because he had been commissioned (in the British Censorship Staff), whereas many regular officers of various ages, anxious to serve, had failed, but also because his language skills had improved vastly since Cheltenham, where his masters judged he was ‘not a linguist by nature’. His position as British Minister on Foreign Office leave from Addis Ababa perhaps led to his acceptance by the army as a temporary recruit for non-active service. Furthermore, he had evidently been passed as fit, with no mention of the heart problem that affected him as a boy, and would cause his premature death in his late forties.

In May 1914 Wilfred Gilbert had given Kathleen a specially bound Book of Common Prayer. Dedicated to her and to their children, he wrote in it a prayer of his own which ended: ‘Give us long years of happiness together in this life, striving always to do Thy will and content to leave the future in Thy hands.’2 In January 1915, at the end of his Foreign Office leave, Wilfred Gilbert, Kathleen and their three sons went back to Addis Ababa. By then Kathleen was pregnant for the fourth time. On 8 November Roderic Miles Doughty Thesiger was born at the British Legation. Susannah having returned to India in 1913, an elderly nurse, known to the children as ‘Nanny’, had been engaged in England to look after one-year-old Dermot and, in due course, baby Roderic.

At Addis Ababa, Captain Thesiger felt concerned that the still-uncrowned Lij Yasu dreamt ‘of one day putting himself at the head of the Mohammadan Abyssinians, and of producing a Moslem kingdom’ that stretched far beyond the boundaries of Abyssinia’s ‘present Empire’.3 Lij Yasu confirmed this fear when, at the Eid festival in Dire Dawa, swearing on the Koran, he professed himself a Muslim. When this was proclaimed to a meeting of chiefs at Addis Ababa there was a riot and shooting that resulted in many dead and wounded. A second meeting proclaimed Menelik’s daughter, Waizero Zauditu, Empress, and the Governor of Harar, Dedjazmatch (later Ras) Tafari, as heir. Thesiger dedicated his autobiography to Tafari’s memory, as the late Emperor. He had admired Tafari unreservedly, despite his wish to modernise Abyssinia, of which Thesiger surely could never have approved. Meanwhile, Tafari marshalled opposition to the deposed Lij Yasu, whose father, Negus Mikael, led the revolt aimed at restoring him to power. Had the revolt succeeded, Islam might have become the official religion of Abyssinia, where there were already Muslim tribes. Thesiger wrote in 1987, ‘Lij Yasu’s restoration would at least [have constituted] a considerable propaganda success for [Muslim] Turkey,’ and might have brought Abyssinia into the First World War on the side of Britain’s enemies, ‘at a time when we were fighting the Germans in East Africa, the Turks in Sinai, Mesopotamia and the Aden Protectorate; and the Dervishes [led by the ‘Mad Mullah’] in Somaliland’.4

As a six-year-old boy, Thesiger remembered seeing Ras Tafari’s baby son, Asfa Wossen, being carried into the Legation in a red cradle for protection. This ‘most embarrassing proof of their confidence’ created an enduring bond between the Thesigers and Tafari which, directly and indirectly, influenced profoundly the course of Thesiger’s future life. Standing at the Legation’s fence, Billy and Brian saw Tafari’s soldiers stream across the plain below, on their way north to Sagale. ‘It was an enthralling, unforgettable sight for a small, romantically minded boy.’ A few days later, during a morning ride, the brothers heard firing. Galloping home, they were told of Tafari’s decisive victory on the Sagale plain, sixty miles north of Addis Ababa, which ended the revolt of Negus Mikael. ‘Forty-four years later,’ Thesiger wrote, ‘I visited the battlefield and saw skulls and bones in crevices on the rocky hillock where Negus Mikael had made his final stand.’5

The victory parades before the Empress Zauditu on Jan Meda field impressed Thesiger enormously. He devoted two pages of The Life of My Choice to his father’s letter describing them and the sight of Negus Mikael led past, humiliated, in chains. Thesiger wrote: ‘Even now, nearly seventy years later, I can recall almost every detail.’ He remembered, and clearly envied, ‘a small boy carried past in triumph – he had killed two men though he seemed little older than myself’.6 Thesiger said he had been reading Tales from the Iliad, and in Ras Tafari’s victory over Negus Mikael and Lij Yasu he could envision ‘the likes of Achilles, Ajax and Ulysses’ as they passed ‘in triumph with aged Priam, proud even in defeat’. This was a piece of dramatic invention. Although H.L. Havell’s Stories from the Iliad was published in 1916, the same year as the Battle of Sagale, Thesiger was given the book only five years later, in July 1921, as an examination prize by R.C.V. Lang, his preparatory school’s headmaster.

More important than this, the 1916 Jan Meda parades inspired Thesiger as a boy to pursue without compromise the adventurous life he would one day lead as a man. He wrote: ‘I believe that day implanted in me a lifelong craving for barbaric splendour, for savagery and colour and the throb of drums, and it gave me a lasting veneration for long-established custom and ritual, from which would derive later a deep-seated resentment of Western innovations in other lands, and a distaste for the drab uniformity of the modern world.’7

In February 1917 Waizero Zauditu was crowned Empress of Abyssinia. Lij Yasu, meanwhile, supported by Ras Yemer, one of Negus Mikael’s officers, raised a force and occupied Magdala, north of Addis Ababa in Wollo province. Confronted by an army from the province of Shoa, he and his followers escaped, only to be defeated in battle, with heavy losses, near Dessie. From there he fled once more into the Danakil country. Having been detained at Fiche for fourteen years, he again escaped before he was finally captured in 1932 and imprisoned at Harar, where he died ‘a physical wreck’ at the age of thirty-seven.

By the end of 1917 the effort and strain of the previous two years had begun to tell on Wilfred Gilbert, whose heart was further weakened by the effects of Addis Ababa’s altitude of eight thousand feet. In December the Thesigers and Minna Buckle travelled to Jibuti, by the now-completed railway linking Addis Ababa and the coast. From Jibuti, Kathleen, Minna and the children sailed along the coast to Berbera, where they stayed with Geoffrey Archer, the Commissioner of British Somaliland, and his wife Olive. Captain Thesiger meanwhile went on via Aden by HMS Fox to Cairo, for talks with the High Commissioner, Sir Reginald Wingate, about the political future of Abyssinia.

Thesiger wrote: ‘Geoffrey Archer…a real giant…six foot four and broad in proportion…lent Brian and me a .410 shotgun and took us shooting along the shore, and when we got back told his skinner to stuff the birds we had shot; I was thrilled by these expeditions.’8 Archer recalled years later how, ‘Firing at the various plovers and sandpipers…skimming close inshore over a placid sea, the children could observe exactly where their shot struck.’ Although Wilfred Gilbert noted that Billy and Brian ‘each shot several kinds of birds’, Geoffrey Archer remembered, ‘Heartrending were the scenes when Brian, the younger…reported to his mother with tears flowing that he had not succeeded in hitting a single bird, while Wilfred, showing signs of a prowess to come, had bagged at least half a dozen.’9

On 3 January 1918 the Thesigers crossed from Berbera in very rough seas to Aden. Wilfred Gilbert, exhausted by his journey to and from Cairo, had been ill in bed for four out of six days at Berbera. During the crossing, he wrote, ‘we were all ill’. In cooler weather at Aden they soon recovered. In Desert, Marsh and Mountain and The Life of My Choice, Thesiger told how the Resident, Major-General J.M. Stewart, took Wilfred Gilbert, Billy and Brian to Lahej in the Aden Protectorate, where they saw British troops shell lines of Turks who had invaded the Protectorate from Yemen. Thesiger’s memory of the trenches and the puffs of white smoke from exploding shells remained clear, but earned him a reputation as a little ‘liar’ at his preparatory school.10 Strangely, none of his father’s letters from Aden mentioned this event. Instead, Wilfred Gilbert wrote: ‘There seems to have been a week’s cessation of hostilities for Christmas. Our men had sports etc while the Turks took the occasion to celebrate a big wedding on their side of the lines. I wanted to take the two eldest boys out this morning to see the aeroplanes working and our guns firing but they were too tired yesterday and it means an early start from here.’11

Wilfred Thesiger’s childhood photograph album, annotated by his father and mother, shows the Archers’ garden with palm trees and their large, dimly-lit drawing room with its tiled floor, Indian carpets and big game trophies on the walls. There are photographs of Billy and Brian riding camels, and one of a small figure in a sun helmet (perhaps Billy) retrieving a shot bird from the sea.

On 3 January the Thesigers sailed from Aden on board a P&O steamer for Bombay. Wilfred Gilbert assured his mother: ‘Kathleen and the children are all well and I think their month at Berbera has done them good altho’ they rather lost their colour.’12 The children had their portraits taken in a photographer’s studio in Bombay. With his thick brown hair carefully brushed and parted, Billy looked very composed in a plain shirt, silk tie and tiepin.

In The Life of My Choice, Thesiger gave a vivid description of the months he and his family spent in India in 1918 with Frederic Chelmsford, Wilfred Gilbert’s eldest brother. Appointed Viceroy in 1916, Chelmsford had a reputation for hard work, a lack of originality, and prejudices which, one senior official observed, appeared to originate in ideas ‘other than his own’.13 Meeting his uncle for the first time in the awe-inspiring surroundings of Delhi’s Viceregal Lodge, Thesiger recalled that he found Frederic Chelmsford impressive and magnificently remote. Since the government buildings designed by Lutyens were not yet complete, the Thesigers lived in ‘palatial tents luxuriously carpeted and furnished, and were looked after by a host of servants’.14 To the seven-year-old Wilfred Thesiger, camping out on this grand scale, amidst ‘pomp and ceremony’, waited on by elaborately turbaned, splendidly uniformed Indian retainers, gave the still seemingly unreal experience added theatrical glamour.

According to Thesiger, the highlight of the visit came when he and Brian joined their father for a tiger shoot in the forests near Jaipur. Here again, Thesiger’s versions, published sixty or seventy years later, do not quite correspond to Wilfred Gilbert’s contemporary description. In his autobiography Thesiger wrote:

Soon after breakfast we set off into the jungle. We saw some wild boar which paid little attention to our passing elephants, and we saw several magnificent peacock and a number of monkeys; to me the monkeys were bandar log, straight out of Kipling’s Jungle Book. It must have taken a couple of hours or more to reach the machan, a platform raised on poles. We climbed up on to it; someone blew a horn and the beat started. After a time I could hear distant shouts. I sat very still, hardly daring to move my head.

A peacock flew past. Then my father slowly raised his rifle and there was the tiger, padding towards us along a narrow game trail, his head moving from side to side. I still remember him as I saw him then. He was magnificent, larger even than I had expected, looking almost red against the pale dry grass. My father fired. I saw the tiger stagger. He roared, bounded off and disappeared into the jungle. He was never found, though they searched for him on elephants while we returned to the palace. I was very conscious of my father’s intense disappointment.15

In 1979 Thesiger had written: ‘I shall never forget sitting, very still, in a machan, hearing the beaters getting closer. Then a nudge [from my father] and looking down to see the tiger, unexpectedly red, move forward just below us.’16 In 1987 he wrote: ‘Two days later we went on another beat, this time for panther, but the panther broke back and we never saw it. However, a great sambhur stag did gallop past the machan.’ He added for emphasis: ‘Scenes such as this remained most vividly in my memory.’17

Describing the tiger shoot in a letter to his mother written on 12 March 1918, Wilfred Gilbert commented: ‘This went wrong unluckily as the tiger stopped in front of the wrong machan at 50 yards and then came to mine and showed just his head out of the grass at 130 yards. It was no good shooting at that and I only got a moving shot at the same distance, hitting him but not badly. He gave a roar and went on and everyone fired without effect. We followed up on elephants and found blood tracks but unluckily he got clean away. The Maharajah [of Jaipur] promised me another but the beat was a failure and he broke back through the line and we never got a glimpse of him. The same happened with a panther drive which was doubly bad luck.’18

The Maharajah’s shikaris had located a sambhur stag in the nearby hills, and after a ‘good climb’ Wilfred Gilbert saw through his binoculars the sambhur’s horns and one ear ‘twitching to keep off the flies’; the rest of the animal was hidden by grass and scrub. Risking a shot from two hundred yards, across a ravine, Wilfred Gilbert wrote: ‘I had to guess where his chest would be…and dropped him stone dead. This bucked us up a bit…but it was very hard that the only shot I missed at Jaipur was the tiger.’19 ‘Billy and Brian…had the time of their lives. They came blackbuck shooting in bullock carts. I got 3 quite good heads [Thesiger remembered only two]; pigsticking also when they and Mary [Buckle] followed us on elephant.’20 Nowhere, however, did he mention Billy being with him on the machan, tense, motionless, waiting for his father to shoot a tiger.

In view of the fact that Thesiger’s recollections, which even as late as 1987 were so vividly detailed, so precise, were yet different from his father’s, it seems he may have combined a vaguer memory of Wilfred Gilbert’s stories with his own much more recent sightings of tiger at Bandhavgarh, Bhopal, in 1983 and 1984. When Thesiger saw these tigers he was writing The Life of My Choice, and was able therefore to describe a (perhaps partly imagined) scene from his childhood as clearly as if it had only just occurred.

The ‘opulence and splendour’ of Jaipur’s court seemed to equal if not surpass the viceregal splendours of Delhi. To Thesiger as a boy what mattered was ‘the all-important hunting’; he admitted he was too young to appreciate the gorgeously ornate palaces, the Maharajah’s courtiers in sumptuous robes. Far more appealing to Billy and Brian was the return crossing from Aden to Jibuti on board HMS Juno after their voyage by P&O liner from Bombay. A Marine band played and the captain fired one of the ship’s guns ‘after [the children] had been given cotton wool to stuff in [their] ears’.21

Six months later, Captain Thesiger was recalled to London by the Foreign Office to report on Abyssinia. He returned to Addis Ababa in December 1918 via Paris, Rome, Taranto and Cairo. The worldwide epidemic of Spanish influenza that claimed more victims than the war itself had struck Cairo, causing many deaths. At Jibuti, Wilfred Gilbert found letters from Addis Ababa. He wrote: ‘Poor Kathleen must have had an awfully anxious time. 4 doctors out of 6 dead, besides a lot of other Europeans and some 13-20,000 Abyssinians. They died like flies and at last ceased even to bury their dead. Billy, Roddy, Dermot and Mary had had it and the compound [was] all down so that they had at times practically no servants.’22 Thesiger wrote in 1987: ‘Ras Tafari sickened. His detractors might well ponder what would have happened to the country had he died.’23 Thesiger remembered his mother had been reading to him A Sporting Trip Through Abyssinia by Major P.H.G. Powell-Cotton. ‘We had got to where Powell-Cotton was at Gondar, trying to shoot a buffalo, and his servant came running down the hill and frightened the buffalo away. My mother thought I looked a bit flushed. She took my temperature and she popped me into bed.’24

By the end of the year, Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger’s duties at Addis Ababa had come to an end. In April 1919 the family travelled together to England for the last time. For Billy, their final exodus from Abyssinia was bewildering; more than a sad occasion, it had been totally incredible: ‘Until almost the last day I could not believe that we were really leaving Abyssinia for good, that we should not be coming back.’25

SIX The Cold, Bleak English Downs

Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen Thesiger, their four children and Mary Buckle (now twenty-seven) arrived back in England in May 1919. To Billy especially England seemed a foreign land, which he remembered only indistinctly from his second visit in 1914 when he was little more than a baby. In his seventies, he said: ‘I had imagined England was like India. I was very disappointed when my father told me that, in England, there were none of the animals or birds I knew. No hyenas, no oryx, no kites. I thought it sounded a deadly, deadly dull country to live in.’1 Thesiger often quoted his writing in conversation, and presumably phrases that originated in his conversations found their way into his books. In his autobiography he had written that, as a child, ‘I thought what a dull place [England] must be.’2

Since the former rectory Captain Thesiger had bought at Beachley in 1911 had been requisitioned by the navy, the family spent the summer in Ireland. They stayed with Kathleen’s relatives at Burgage, before moving to Ballynoe, a rented house fourteen miles from Burgage on the River Slaney. Wilfred Gilbert wrote: ‘there is good fishing…also rough shooting. The house is very well kept with pretty gardens.’3 Billy shot his first rabbit at the Dyke on the Burgage estate. At Ballynoe he went ferreting. Later that year, at Okehampton on Dartmoor, ‘much to his joy’,4 he shot his first running rabbit, with a double-barrelled Purdey .410 shotgun he and Brian had been given in 1918 by Wilfred Gilbert’s brother Percy. (Wilfred Gilbert had brought the gun back with him from England to Addis Ababa, where the boys used it to shoot pigeons that perched on the roof of the Italian Legation.) Billy enjoyed watching his father paint, or fish for salmon in the Slaney. He ‘became enthusiastic’ when Wilfred Gilbert ‘tried to teach [him] to sketch’5 and thought the boy’s first efforts showed promise.

Friends came to stay, including Billy’s godmother Mrs Curre, and Hugh Dodds who had served under Wilfred Gilbert as a Consul in Abyssinia. At Burgage, Wilfred Gilbert had to ‘stay in bed for breakfast and rest after lunch and in general [take life] very easily’. He continued to rest at Ballynoe, untroubled except by a shortage of water from the well due to an unusually dry summer.6 His posting after Addis Ababa as Consul-General in New York had to be delayed until his health improved. In a ‘private letter’ the Foreign Office had proposed to raise Wilfred Gilbert’s allowances, making his official income £5000 a year, enough to pay for ‘a good deal of entertaining’ and ‘to keep a motor car’, which he emphasised would be ‘essential’. He wrote, ‘Kathleen is quite pleased with the idea of New York now that I am to keep my rank and the pay is to be increased. It is not yet decided how we shall manage affairs but probably I may go out first while she stays over the boys’ first holidays [from school] and would then come on with the babies.’7 Everything depended, however, upon a significant improvement in Captain Thesiger’s health.

In September the family visited Dublin to buy school uniforms for Billy and Brian, and to enable Wilfred Gilbert to consult a heart specialist, who found him ‘perfectly sound and with very low blood pressure’. Wilfred Gilbert wrote: ‘I suppose [this] accounts for the breathlessness and general slackness and he says I must take things quietly. I have I think put on nearly a stone in weight which is probably to the good but it is a long and tiresome business getting fit again…Dr Moorhead…said there was nothing wrong with me organically but that the heart muscles are weak and blood pressure still very low and he added that it would take some time to get over the general strain. He had seen many younger men from the War in the same state and found that it usually took about a year to put right…It is no use trying to go to New York until I am really fit as I should only break up and…might then get a dilation of the heart, whereas if [I] wait and get fit now there won’t be the smallest chance of anything.’8

After leaving Ireland, Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen arranged to stay with Geoffrey and Olive Archer at Horsham in Sussex, then to spend a month or six weeks in Brighton, ‘having a perfectly quiet time’, until Wilfred Gilbert had recovered enough to take up his consular posting in New York. But any hopes of starting work were finally dashed by the Archers’ doctor, who confirmed that Wilfred Gilbert must rest for a year, or risk damaging his heart. Wilfred Gilbert wrote: ‘All the doctors say the same thing so one must accept it. I have told the [Foreign Office] I will come and see them.’9 The Thesigers rented rooms with sea views at number 4 Marine Parade in Brighton, a few minutes’ walk from the beach. Kathleen’s mother, who kept a flat nearby, became a frequent visitor.

In September 1919 Billy and Brian began their first term as boarders at St Aubyn’s, a preparatory school in the village of Rottingdean, three miles along the coast, due east from Brighton. Their parents had visited the school, where some of Wilfred Gilbert’s relatives had been educated, and met R.C.V. Lang, the new headmaster. Thesiger said: ‘My father and mother were evidently impressed by him and this convinced them we should go there. I remember my father took us to Eton about that time. I asked him: “Is this where I am going?”, and he replied, “Yes, one day.” We saw boys rowing on the river and I remember the boats banged into one another and one of the boys hurt his hand.’10

In those days St Aubyn’s ‘Sunday’ uniform, worn by boys travelling to the school and on special occasions, consisted of a three-piece worsted suit and a bowler hat. In these adult clothes Billy and Brian looked very odd indeed. Boys of their age certainly looked, and no doubt felt, more comfortable in the more practical everyday uniform, consisting of grey shorts and a matching grey jersey. When Thesiger visited the school sixty years later, he wrote: ‘Time seemed to have stood still. The boys wore the same grey shorts and jerseys; the band was practising, marching and countermarching on the playing field. I attended morning chapel and neither the seating nor the service had altered.’11

Until the 1970s, during visits to London Thesiger still wore a three-piece suit and a bowler hat, clothes more appropriate for a civil servant than a desert explorer. More to the point, these old-fashioned clothes made him increasingly conspicuous, something he disliked, and claimed he had always avoided. In A Reed Shaken by the Wind, Gavin Maxwell described Thesiger as he first saw him in London in 1954: ‘He was very unlike the preconceived theories I had held about his appearance…The bowler hat, the hard collar and black shoes, the never-opened umbrella, all these were a surprise to me.’12 Thesiger’s response was very reasonable, though predictably tart: ‘When I’m in London I put on a dark suit and I know I’m wearing the right clothes for lunch at The Travellers, or for going out somewhere in the evening. I use an umbrella like a walking-stick and, besides, it’s useful if it rains…I admit, I gave up wearing a bowler because no one else wore one. As for not looking like an explorer: I’d be very interested to know just what an explorer is supposed to look like. Surely I’m not expected to turn up at my club wearing shorts and a bush shirt!’13 Thesiger did concede, however, that Maxwell’s description worked as a literary device by creating a contrast between his appearance in two different worlds: England and the Iraqi marshes.

On his first day at St Aubyn’s, Thesiger tells us that he went round shouting, ‘Has anyone seen Brian?’ instead of ‘Thesiger Minor’. He added: ‘I was not allowed to forget this appalling solecism.’14 His upbringing in Abyssinia had left him quite unprepared for the busy communal life of an English private school. Yet he maintained: ‘You would be quite wrong saying I was desperately unhappy at St Aubyn’s. It was more a feeling of being isolated. They did gang up on me rather…at night in the dormitory. I don’t mean in a physical sense. I could take care of myself that way. It was being out of it all, being isolated. You were only by yourself at night after you went to bed, and getting yourself up in the morning. There were always people, boys, in your room. It’s probably true that I was used to sleeping by myself at Addis Ababa…at St Aubyn’s I didn’t like sleeping in a dorm with the others.’15 ‘My father and mother used to visit us at weekends. Not every weekend, of course, but pretty frequently. They’d watch us playing games and so on, and we rather wished that they wouldn’t.’16

Soon after the brothers first arrived, they had been questioned about their parents and their home life. Thesiger wrote: ‘At first I was a friendly, forthcoming little boy, very ready to talk, perhaps to boast about journeys I had made and things I had seen. My stories, however, were greeted with disbelief and derision, and I felt increasingly rejected.’17 (He remembered boys exclaiming: ‘Have you heard what Thesiger Major says? He says he was in the trenches in the War.’18) ‘As a result I withdrew into myself, treated overtures of friendship with mistrust, and was easily provoked. I made few friends, but once I adapted to this life I do not think I was particularly unhappy. I could comfort myself, especially at night, by recalling the sights and scenery of Abyssinia, far more real to me than the cold bleak English downs behind the school.’19 Billy grew quarrelsome and aggressive. He fought in the gymnasium with a boy named Lucas, grasping him by the throat until he sank down unconscious: ‘This did not increase my popularity.’20 While he remembered being thrashed for various minor offences at St Aubyn’s – and later, at Eton, being caned or birched for idleness – his attack on Lucas apparently went unpunished.

Thesiger’s cousin, the actor Ernest Thesiger, described his own very similar experiences at a private school in his 1927 autobiography, Practically True. Like Wilfred, being outspoken was a major cause of Ernest’s problems. Unlike Wilfred, he was bullied. Ernest wrote: ‘I had never been a particularly happy child. At my private school I had been bullied by my contemporaries and disliked by my masters, both, probably, for the same reason, namely that I possessed a somewhat unbridled tongue combined with an uncomfortable knack of finding out people’s weak spots. This does not make for popularity, and should be held in check by those not physically strong enough to protect themselves.’ Ernest added: ‘To be unusual or unconventional was the one sin not forgiven by the British schoolboy.’21

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.