Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Wonders of the Solar System Text Only»

TEXT ONLY EBOOK EDITION

For Gia, George and Mo, who kept our family together whilst I was away filming Wonders.

Brian Cox

For Anna, Benjamin, Martha and Theo, the true wonders of my solar system.

Andrew Cohen

Contents

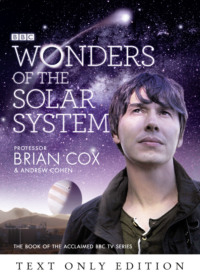

Cover

Title Page

CHAPTER 1 - THE WONDER

CHAPTER 1 - THE WONDER

CHAPTER 2 - EMPIRE OF THE SUN

CHAPTER 2 - EMPIRE OF THE SUN

CHAPTER 3 - ORDER OUT OF CHAOS

CHAPTER 3 - ORDER OUT OF CHAOS

CHAPTER 4 - THE THIN BLUE LINE

CHAPTER 4 - THE THIN BLUE LINE

CHAPTER 5 - DEAD OR ALIVE

CHAPTER 5 - DEAD OR ALIVE

CHAPTER 6 - ALIENS

CHAPTER 6 - ALIENS

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

On a frosty winter’s afternoon the day after New Year 1959, a tiny metal sphere named First Cosmic Ship ascended, gently at first but with increasing ferocity, into a January sky above the Baikonur Cosmodrome a hundred miles east of the Aral Sea. Just a few minutes into her flight the little spacecraft separated from the third stage of her rocket and became the first man-made object to escape the gravitational grasp of planet Earth. On 4 January she passed by the Moon and entered a 450-day long orbit around the Sun somewhere between Earth and Mars, where she remains today. First Cosmic Ship, subsequently renamed Luna 1, is the oldest artificial planet and mankind’s first explorer of the Solar System.

Half a century later, we have launched an armada of robot emissaries and twenty-one human explorers beyond Earth’s gravitational grip and onwards to our neighbouring worlds. Five of our little craft have even escaped the gravitational embrace of the Sun on journeys that will ultimately take them to the stars. No longer confined to Earth, we now roam freely throughout the Empire of the Sun.

Our spacecraft have returned travellers’ tales and gifts beyond value; an explorer’s bounty that easily rivals the treasures, both material and intellectual, from the voyages of Magellan, Drake, Cook and their fellow navigators of Earth’s oceans. As with all exploration, the journeys have been costly and difficult, but the rewards are priceless.

Our first half-century of space exploration – less than a human lifetime – has revealed that our Solar System is truly a place of wonders. There are worlds beset with violence and dappled with oases of calm; worlds of fire and ice, searing heat and intense cold; planets with winds beyond the harshest of terrestrial hurricanes and moons with great sub-surface oceans of water. In one corner of the Sun’s empire there are planets where lead would flow molten across the surface, in another there are potential habitats for life beyond Earth. There are fountains of ice, volcanic plumes of sulphurous gases rising high into skies bathed in radiation and giant gas worlds ringed with pristine frozen water. A billion tiny worlds of rock and ice orbit our middle-aged yellowing Sun, stretching a quarter of the way to our nearest stellar neighbour, Proxima Centauri. What an empire of riches, and what a subject for a television series.

There are worlds of searing heat and intense cold; planets with winds beyond the harshest of terrestrial hurricanes and moons with great sub-surface oceans of water.

When we first began discussing making Wonders of the Solar System, we quickly realised that there is much more to the exploration of space than the spectacular imagery and surprising facts and figures returned by our robot spacefarers. Each mission has contributed new pieces to a subtle and complex jigsaw, and as the voyages have multiplied, a greatly expanded picture of the majestic arena within which we live our lives has been revealed. Mission by mission, piece by piece, we have learnt that our environment does not stop at the top of our atmosphere. The subtle and complex gravitational interactions of the planets with our Sun and the billions of lumps of rock and ice in orbit around it have directly influenced the evolution of the Earth over the 4.5 billion years since its formation, and that influence continues today.

Our moon, unusually large for a satellite in relation to its parent planet, is thought to stabilise our seasons and therefore may have played an important role in allowing complex life on Earth to develop; we probably need our moon.

It is thought that comets from the far reaches of the outer Solar System delivered much of the water in Earth’s oceans in a violent bombardment only half a billion years after our home planet formed. This event, known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, is thought to have been the result of an intense gravitational dance between the giant planets of our Solar System, Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune. Without this chance, violent intervention, there may have been little or no water on our planet; we probably need the comets, Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune.

More worryingly for us today, we have no reason to assume that this often-violent interaction with the other inhabitants of the Solar System has ceased; colossal lumps of rock and ice will visit us again from the distant vaults of the outer Solar System, and if undetected and unprepared for, we may not survive. It is thought that this very real threat is diminished by the gravitational influence of Jupiter on passing comets and asteroids, deflecting many of them out of our way; we probably need Jupiter.

This picture of the Solar System as a complex, interwoven and interacting environment stretching way beyond the top of our atmosphere is one of the central stories running throughout the series. In order to understand our place in space we must lift our eyes upwards from Earth’s horizon and gaze outwards across a vast sphere extending perhaps for a light year beyond the Kuiper belt of comets and onwards to the edge of the Oort cloud of ice-worlds surrounding the Sun.

Reaching for worlds beyond our grasp is an essential driver of progress and necessary sustenance for the human spirit. Curiosity is the rocket fuel that powers our civilization.

Our exploration of the Solar System has also given us very valuable insights into some of the most pressing and urgent problems we face today. Understanding the Earth’s complex weather and climate system, and how it responds to changes such as the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, is perhaps the greatest challenge for early twenty-first century science. This is a planetary science challenge: Earth is one example of a planet with an atmosphere of a particular chemical composition, orbiting the Sun at a particular distance. For a scientist, having only one example of such a vast and interdependent system is less than ideal, and makes the task of understanding its subtle and complex behaviour tremendously difficult. Fortunately, we do have more than one example. Our Solar System is a cosmic laboratory, a diverse collection of hundreds of worlds, large and small, hot and cold. Some orbit closer to our star than we do, most are vastly further away. Some have atmospheres rich in greenhouse gases, far denser than our own, others have lost all but faint traces of their atmospheres to the vacuum of space. Our two planetary neighbours, Venus and Mars, are salient examples of what can happen to worlds very similar to Earth if conditions are slightly different. Venus experienced a runaway greenhouse effect that raised its surface temperature to over 400 degrees Celsius and atmospheric pressure to ninety times that of Earth. Because the laws of physics that control the evolution of planetary atmospheres are the same on Earth and Venus, our understanding of the Greenhouse Effect on Earth can be transferred to and tested on Venus. This provides valuable additional information that can be used to tune and improve those models. The discovery that this benign, blue planet which shimmers brightly and with such beauty in the twilight skies of Earth was transformed long ago into a hellish world of searing temperatures, acid rain and crushing pressure has had a genuine and profound psychological effect because it demonstrates in stark terms that runaway greenhouse effects can happen to planets not too dissimilar from our own.

Similar salutary insights have accrued from our studies of Mars. In the early days of Mars exploration, observations of the evolution of dust storms on the red planet provided support for the nuclear winter hypothesis on Earth. Storms that began in small local areas were observed to throw large amounts of dust into the Martian atmosphere. Over a period of a few weeks, the dust encircled the entire planet, exactly matching the models of the evolution of the dust and smoke clouds that would be created by a large-scale nuclear exchange. When a planet is shrouded in dust, the warmth of the Sun is reflected back into space and temperatures quickly fall, leading to a so-called nuclear winter that could last many decades. On Earth, this could lead to the extinction of many species, including perhaps our own.

The observation of a mini-nuclear winter periodically playing itself out on Mars was a major factor in the acceptance of the theory, and this in turn profoundly influenced the thinking of major players at the end of the cold war. As former Russian president Mikhail Gorbachev said in 2000, ‘Models made by Russian and American scientists showed that a nuclear war would result in a nuclear winter that would be extremely destructive to all life on Earth; the knowledge of that was a great stimulus to us, to people of honor and morality, to act in that situation’.

Wonders is also a story of human ingenuity and engineering excellence. Russia’s First Cosmic Ship began its voyage beyond Earth just fifty-five years after the first powered flight by Orville and Wilbur Wright in December 1903. Wright Flyer 1 was constructed from spruce and muslin, and powered by a twelve-horsepower petrol engine assembled in a bicycle repair shop. By 1969, less than one human lifetime away, Armstrong and Aldrin set foot on another world, launched by a Saturn V rocket whose giant first-stage engines generated around 180 million horsepower between them. The most powerful and evocative flying machine ever built, the Moon rocket stood 111 metres (364 feet) high, just thirty centimetres (twelve inches) short of the dome of Wren’s magisterial St Paul’s Cathedral. Fully fuelled for a lunar voyage, it weighed 3,000 tonnes. Sixty-six years before Apollo 11’s half-a-million mile round trip to the Moon, Wright Flyer 1 reached an altitude of three metres (ten feet) on its maiden voyage. This rate of technological advancement, culminating with our first journeys into the deep Solar System, is surely unparalleled in human history, and the benefits are practically incalculable.

Most importantly of all, Wonders is a celebration of the spirit of exploration. This is desperately relevant, an idea so important that celebration is perhaps too weak a word. It is a plea for the spirit of the navigators of the seas and the pioneers of aviation and spaceflight to be restored and cherished; a case made to the viewer and reader that reaching for worlds beyond our grasp is an essential driver of progress and necessary sustenance for the human spirit. Curiosity is the rocket fuel that powers our civilization. If we deny this innate and powerful urge, perhaps because earthly concerns seem more worthy or pressing, then the borders of our intellectual and physical domain will shrink with our ambitions. We are part of a much wider ecosystem, and our prosperity and even long-term survival are contingent on our understanding of it.

‘Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, “Because it is there.” Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the Moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.’

— John F. Kennedy, Rice University 1962

In 1962, John F. Kennedy made one of the great political speeches at Rice University in Houston, Texas. In the speech, he argued the case for America’s costly and wildly ambitious conquest of the Moon. Imagine the bravado, the sheer power and confidence of vision in committing to a journey across a quarter of a million miles of space, landing on another world and returning safely to Earth. It might have been perceived as hubris at the time, but it worked. America achieved this most audacious feat of human ingenuity within nine years of launching their first manned sub-orbital flight. Next time you glance up at our shimmering satellite, give a thought to the human beings just like you who decided to go there and plant their flag for all mankind.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the Solar System is our civilization’s frontier. Our first steps into the unexplored lands above our heads have been wildly successful, revealing a treasure chest of new worlds and giving us priceless insights into our planet’s unique beauty and fragility. As a species, we are constantly balanced on a knife-edge, prone to parochial disputes and unable to harness our powerful curiosity and boundless ingenuity. The exploration of the Solar System has brought out the best in us, and this is a precious gift. It rips away our worst instincts and forcibly thrusts us into a face-to-face encounter with the best. We are compelled to understand that we are one species amongst millions, living on one planet around one star amongst billions, inside one galaxy amongst trillions. The beauty of our planet is made manifest, enhanced immeasurably by the juxtaposition with other worlds. Ultimately, the value of young, curious and wonderful humanity as we take our first steps outwards from our home world is brought into such startling relief that all who share in the wonder must surely be filled with optimism and a powerful desire to continue this most valuable of journeys.

CHAPTER 2

AN ORDINARY STAR

At the heart of our complex and fascinating Solar System sits its powerhouse. For us it is everything, and yet it is just one ordinary star amongst 200 billion stars within our galaxy. It is a large wonder that greets us every morning; a star that controls each and every world that it holds in its thrall – the Sun. The Sun reigns over a vast empire of worlds and without it we would be nothing; life on Earth would not exist. Although we live in the wonderous empire of the Sun, it is a place we can never hope to visit. However, thanks to the continual advances in technology and space exploration, and through observation from here on Earth, each spectacular detail we see leads us closer to understanding the enigma that is the Sun.

In the north of India, on the banks of the river Ganges, lies the holy city of Varanasi. It is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, and for Hindus it is one of the holiest sites in all of India.

Varanasi, or Banares, to give the city its old name, is a city suffused with the colours, sounds and smells of a more ancient India. Mark Twain famously wrote: ‘Banares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together’.

Each year a million pilgrims visit Varanasi to bathe in the holy river and pray in the hundreds of temples that cover the city. Part of what makes the city so special is the orientation of its sacred river as it flows past; it’s the only place where the Ganges turns around to the north, making it the one spot on the river where you can bathe while watching the Sun rise on the eastern shore. And sunrise over Varanasi is certainly one of Earth’s great sights. The humid, tropical air adds a soporific quality to the light, which in turn lends a fairy-tale quality to the brightly coloured buildings and palaces that line the holy river. It is a misty, pastel-shaded, dream-like experience, as though the city is materialising not from the dawn but from the past.

But on 22 July 2009, at precisely 6.24am, a different type of pilgrim was to be found waiting beside the Ganges to witness one of the true wonders of the Solar System.

At this time, across a small strip of the Earth’s surface, the longest total eclipse of the Sun since June 1991 was about to be visible to a lucky few. For three and a half minutes the Moon would cover the face of the Sun and plunge this ancient city into darkness.

SOLAR ECLIPSES

A total solar eclipse is possibly the most visual and visceral example of the structure and rhythm of our solar system. It is a very human experience, and one that lays bare the mechanics of this system.

At the centre is the Sun, reigning over an empire of worlds that move like clockwork. Everything within its realm obeys the laws of celestial mechanics discovered by Sir Isaac Newton in the late seventeenth century. These laws allow us to predict exactly where every world will be for centuries to come. And wherever you happen to be, if there’s a moon between you and the Sun, there will be a solar eclipse at some point in time.

Eclipses occur all over the Solar System; Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune all have moons and so eclipses around these planets are a frequent occurrence. On Saturn, the moon Titan passes between the Sun and the ringed planet every fifteen years, while on the planetoid Pluto, eclipses with its large moon, Charon, occur in bursts every 12o years. But the king of eclipses is the gas giant Jupiter; with four large moons orbiting the planet, it’s common to see the shadow of moons such as Io, Ganymede and Europa moving across the Jovian cloud tops. Occasionally the eclipses can be even more spectacular. In spring 2004, the Hubble telescope took a rare picture (opposite top) in which you can see the shadows of three moons on Jupiter’s surface; three eclipses occurring simultaneously. Although this kind of event happens only once every few decades, the timing of Jupiter’s eclipses is as predictable as every other celestial event. For hundreds of years we’ve been able to look up at the night sky and know exactly what will happen when. Historically, this precise understanding of the motion of the Solar System provided the foundation upon which a much deeper understanding of the structure and workings of our universe rests. A wonderful example is the extraordinary calculation performed by the little-known Dutch astronomer Ole Romer in the 1670s. Romer was one of many astronomers who attempted to solve a puzzle that seemed to make no sense.

The eclipses of the Galilean moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, by Jupiter were accurately predicted once their orbits had been plotted and understood. But it was soon observed that the moons vanished and reappeared behind Jupiter’s disc about twenty minutes later than expected when Jupiter was on the far side of the Sun (the accurate modern figure is seventeen minutes). When the predictions of a scientific theory disagree with evidence the theory must be modified or even rejected, unless an explanation can be found. Newton’s beautiful clockwork Solar System was on trail.

Romer was the first to realise that this delay was not a glitch in the clockwork Solar System. Instead, it was caused because light takes time to travel from Jupiter to Earth. The eclipses of the Galilean moons happen just as Newton predicts, but we don’t see the eclipses on earth until slightly later than predicted when Jupiter moves further away from the Earth, simply because it takes more time for light to travel a greater distance.

From this beautifully simple observation of the eclipses of Jupiter, fellow Dutch astronomer, Christian Huygens, was able to make the first calculation of the speed of light. The speed of light, we now know, is a fundamental property of our universe. It is one of the universal numbers that is unchanging and fixed throughout the cosmos. Ultimately, an understanding of its true significance had to wait until Einstein’s theory of space and time, Special Relativity, in 1905, but the long and winding road of discovery can be traced back to Romer and his eclipses.

Closer to home, eclipses become even more familiar. In 2004, the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity looked up from the surface of Mars and took possibly the most beautiful picture of any extraterrestrial eclipse (opposite bottom). In this remarkable image you can see Mars’ moon Phobos as it makes its way across the Sun – an image of a partial solar eclipse from the surface of another world.

Eclipses on Mars are not only possible but commonplace, with hundreds occurring each year, but one event we will never see on Mars is a total solar eclipse. Here on Earth, though, humans have the best seat in the Solar System from which to enjoy the spectacle of a total eclipse of the Sun – all thanks to a wonderful quirk of fate.

For a perfect total solar eclipse to occur, a moon must appear to be exactly the same size in the sky as the Sun. On every other planet in the Solar System the moons are the wrong size and the wrong distance from the Sun to create the perfect perspective of a total solar eclipse. However, here on Earth the heavens have arranged themselves in perfect order. The Sun is 400 times the diameter of the Moon and, by sheer coincidence, it’s also 400 times further away from the Earth. So when our moon passes in front of the Sun it can completely obscure it.

With over 150 moons in the Solar System you might expect to find other total solar eclipses, but none produce such perfect eclipses as the Earth’s moon. It won’t last forever, though; The clockwork of the Solar System is such that the raising of the tides on Earth caused by the Moon has consequences. As the Earth spins beneath tidal bulges raised by the Moon, its rate of rotation is gradually, almost imperceptibly, reduced by friction, and this has the effect of causing the Moon to gradually drift further and further away from Earth. This complex dance, in precise accord with Newton’s laws, is also responsible for the fact that we only see one side of the Moon from the Earth – a phenomenon called spin-orbit locking.

The drift is tiny, only around 4 centimetres (1.6 inches) per year, but over the vast expanses of geological time it all adds up. Around 65 million years ago the Moon was much closer to Earth and the dinosaurs would not have been able to see the perfect eclipses we see today. The Moon would have been closer to Earth and would therefore have completely blotted out the Sun with room to spare. In the future, as the Moon moves away from the Earth, the unique alignment will slowly begin to degrade; while drifting away from our planet the Moon will become smaller in the sky and eventually too small to cover the Sun. This accidental arrangement of the Solar System means that we are now living in exactly the right place and at exactly the right time to enjoy the most precious of astronomical events.

IN THE REALM OF THE SUN

Our closest star is the strangest, most alien place in the Solar System. It’s a place we can never hope to visit, but through space exploration and a few chance discoveries our generation is getting to know the Sun in exquisite new detail. For us it’s everything, and yet it’s just one ordinary star among 200 billion starry wonders that make up our galaxy. To explore the realm of our sun requires a journey of over thirteen billion kilometres; a journey that takes us from temperatures reaching fifteen million degrees Celsius, in the heart of our star, to the frozen edge of the Solar System where the Sun’s warmth has long disappeared.

On 14 November 2003, three American scientists discovered a dwarf planet at the remotest frontier of the Solar System. Sedna is a planetoid three times more distant from the Sun than Neptune. Around 1,600 kilometres (1,000 miles) in diameter, Sedna is barely touched by the Sun’s warmth; its surface temperature never rises above minus -240 degrees Celsius. For most of its orbit Sedna is further from our star than any other known dwarf planet. On its slow journey around the Sun, one complete orbit – Sedna’s year – takes 12,000 Earth years. From its frozen surface at least thirteen billion kilometres from Earth, a view of the Sun rising on Sedna would give a very different perspective on our solar system and a clear depiction of how far the Sun’s realm stretches. Sunrise on Sedna is no more than the rising of a star in the night sky: from this frozen place, our blazing sun is just another star.

To travel from the outer reaches of Sedna’s orbit to one of the first true planets of the Solar System we would need to cover over ten billion kilometres. Uranus was the first planet to be discovered with the use of a telescope, in 1781, by Sir William Herschel, and like all the giant planets (except Neptune) it is visible with the naked eye. Even so, sunrise on Uranus is barely perceptible; the Sun hangs in the sky 300 times smaller than it appears on Earth. Only when we have travelled the two and a half billion kilometres past Jupiter and Saturn do we arrive at the first world with a more familiar view of the Sun. Over 200 million kilometres out, sunset on Mars is a strangely familiar sight. On 19 May 2005, the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit captured this eerie view as the Sun sank below the rim of the Gusev crater. The panoramic mosaic image was taken by the rover at 6.07pm, on the rover’s 489th day of residency on the red planet. This sunset shot is not only beautiful, but it also tells us something fundamental about the Martian sky. Repeated observations have revealed that twilight on Mars is a rather long affair, lasting for up to two hours before sunrise and two hours after sunset. The reason for this long slow progression to and from darkness is the fine dust that is whipped up off the surface of Mars and lifted to incredibly high altitudes. At this height the Sun’s rays are scattered by the dust from the sunlit side of Mars around to the dark side, producing the long, leisurely and beautiful journey between day and night. Here on Earth, some of the longest and most spectacular sunrises and sunsets are produced by a similar mechanism, when tiny dust grains are catapulted high into the atmosphere by powerful volcanoes, scattering light into extra-colourful moments on our planet.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.