Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

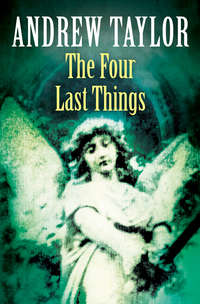

Kitabı oku: «The Four Last Things»

ANDREW TAYLOR

THE FOUR LAST THINGS

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Epilogue

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

‘In brief, we all are monsters, that is, a composition of Man and Beast …’

Religio Medici, I, 55

All his life Eddie had believed in Father Christmas. In childhood his belief had been unthinking and literal; he clung to it for longer than his contemporaries and abandoned it only with regret. In its place came another conviction, another Father Christmas: less defined than the first and therefore less vulnerable.

This Father Christmas was a private deity, the source of small miracles and unexpected joys. This Father Christmas – who else? – was responsible for Lucy Appleyard.

Lucy was standing in the yard at the back of Carla Vaughan’s house. Eddie was in the shadows of the alleyway, but Lucy was next to a lighted window and there could be no mistake. It was raining, and her dark hair was flecked with drops of water that gleamed like pearls. The sight of her took his breath away. It was as if she were waiting for him. An early present, he thought, gift-wrapped for Christmas. He moved closer and stopped at the gate.

‘Hello.’ He kept his voice soft and low. ‘Hello, Lucy.’

She did not reply. Nor did she seem to register his use of her name. Her self-possession frightened Eddie. He had never been like that and never would be. For a long moment they stared at each other. She was wearing what Eddie recognized as her main outdoor coat – a green quilted affair with a hood; it was too large for her and made her look younger than she was. Her hands, almost hidden by the cuffs, were clasped in front of her. He thought she was holding something. On her feet she wore the red cowboy boots.

Behind her the back door was closed. There were lights in the house but no sign of movement. Eddie had never been as close to her as this. If he leant forward, and stretched out his hand, he would be able to touch her.

‘Soon be Christmas,’ he said. ‘Three and a half weeks, is it?’

Lucy tossed her head: four years old and already a coquette.

‘Have you written to Santa Claus? Told him what you’d like?’

She stared at him. Then she nodded.

‘So what have you asked him for?’

‘Lots of things.’ She spoke well for her age, articulation clear, the voice well-modulated. She glanced back at the lighted windows of the house. The movement revealed what she was carrying: a purse, too large to be hers, surely? She turned back to him. ‘Who are you?’

Eddie stroked his beard. ‘I work for Father Christmas.’ There was a long silence, and he wondered if he’d gone too far. ‘How do you think he gets into all those houses?’ He waved his hand along the terrace, at a vista of roofs and chimneys, outhouses and satellite dishes; the terrace backed on to another terrace, and Eddie was standing in the alley which ran between the two rows of backyards.

Lucy followed the direction of his wave with her eyes, raising herself on the toes of one foot, a miniature ballerina. She shrugged.

‘Just think of them. Millions of houses, all over London, all over the world.’ He watched her thinking about it, her eyes growing larger. ‘Chimneys aren’t much use – hardly anyone these days has proper fires, do they? But he has other ways in and out. I can’t tell you about that. It’s a secret.’

‘A secret,’ she echoed.

‘In the weeks before Christmas, he sends me and a few others around to see where the problems might be, what’s the best way in. Some houses are very difficult, and flats can be even worse.’

She nodded. An intelligent child, he thought: she had already begun to think out the implications of Santa Claus and his alleged activities. He remembered trying to cope with the problems himself. How did a stout gentleman carrying a large sack manage to get into all those homes on Christmas Eve? How did he get all the toys in the sack? Why didn’t parents see him? The difficulties could only be resolved if one allowed him magical, or at least supernatural, powers. Lucy hadn’t reached that point yet: she might be puzzled but at present she lacked the ability to follow her doubts to their logical conclusions. She still lived in an age of faith. Faced with something she did not understand, she would automatically assume that the failure was hers.

Eddie’s skin tingled. His senses were on the alert, monitoring not only Lucy but the houses and gardens around them. It was early evening; at this time of year, on the cusp between autumn and winter, darkness came early. The day had been raw, gloomy and damp. He had seen no one since he turned into the alleyway.

Traffic passed in the distance; the faint but insistent rhythm of a disco bass pattern underpinned the howl of a distant siren, probably on the Harrow Road; but here everything was quiet. London was full of these unexpected pools of silence. The streetlights were coming on and the sky above the rooftops was tinged an unhealthy yellow.

‘You look as if you’re going out.’ Eddie knew at once that this had been the wrong thing to say. Once again Lucy glanced back at the house, measuring the distance between herself and the back door. Hard on the heels of this realization came another: perhaps she wasn’t afraid of Eddie but of outraged authority on the other side of that door.

He blurted out, ‘It’s a nice evening for a walk.’ Idiotic or not, the remark seemed to have a relaxing effect on Lucy. She turned back to him, peering up at his face.

He rested his arms along the top of the gate. ‘Are you going out?’ he asked, politely interested, talking as one adult to another.

Again the toss of the head: this time inviting a clash of wills. ‘I’m going to Woolworth’s.’

‘What are you going to buy?’

She lowered her voice. ‘A conjur—’ The word eluded her and she swiftly found a substitute: ‘A magic set. So I can do tricks. See – I’ve got my purse.’ She held it out: a substantial oblong, made for the handbag not the pocket; designed for an adult, not a child.

Eddie took a long, deep breath. Suddenly it was hard to breathe. There always came a point when one crossed the boundary between the permissible and the forbidden. He knew that Angel would be furious. Angel believed in careful preparation, in following a plan; that way, she said, no one got hurt. She hated anything which smacked of improvisation. His heart almost failed him at the thought of her reaction.

Yet how could he turn away from this chance? Lucy was offering herself to him, his Christmas present. Had anyone ever had such a lovely present? But what if someone saw them? He was afraid, and the fear was wrapped up with desire.

‘Is it far?’ Lucy asked. ‘Woolworth’s, I mean.’

‘Not really. Are you going there now?’

‘I might.’ Again she glanced back at the house. ‘The gate’s locked. There’s a bolt.’

The gate was a little over four feet high. Eddie put his left hand over and felt until he found the bolt. He had to work it to and fro to loosen it in its socket; it was too stiff for a child of Lucy’s age, even if she could have reached it. At last it slid back, metal smacking on metal. He tensed, waiting for opening doors, for faces at the windows, for dogs to bark, for angry questions. He guessed from her stillness that Lucy too was waiting. Their shared tension made them comrades.

Eddie pushed the gate: it swung into the yard with a creak like a long sigh. Lucy stepped backwards. Her face was pale, intent and unreadable.

‘Are you coming?’ He made as if to turn away, knowing that the last thing he must seem was threatening. ‘I’ll give you a ride there in my van if you want. We’ll be back in a few minutes.’

Lucy looked back at the house again.

‘Don’t worry about Carla. You’ll be back before she notices you’re gone.’

‘You know Carla?’

‘Of course I do.’ Eddie was on safer ground here. ‘I told you that I worked for Father Christmas. He knows everything. I saw you with her yesterday in the library. Do you remember? I winked at you.’

The quality of Lucy’s silence changed. She was curious now, perhaps relieved.

‘And I saw you at St George’s the other Sunday, too. Your mummy’s called Sally and your daddy’s called Michael.’

‘You know them too?’

‘Father Christmas knows everyone.’

Still she lingered. ‘Carla will be cross.’

‘She won’t be cross with either of us. Not if she wants any Christmas presents this year.’

‘Carla wants to win the Lottery for Christmas. I know. I asked her.’

‘We’ll have to see.’

Eddie took a step down the alleyway. He stopped, turned back and held out his hand to Lucy. Without a backward glance, she slipped through the open gate and put her hand in his.

1

‘Who can but pity the merciful intention of those hands that do destroy themselves? the Devil, were it in his power, would do the like …’

Religio Medici, I, 51

‘God does not change,’ said the Reverend Sally Appleyard. ‘But we do.’

She stopped and stared down the church. It wasn’t that she didn’t know what to say next, nor that she was afraid: but time itself was suddenly paralysed. As time could not move, all time was present.

She had had these attacks since childhood, though less frequently since she had left adolescence behind; often they occurred near the start of an emotional upheaval. They were characterized by a dreamlike sense of inevitability – similar, Sally suspected, to the preliminaries to an epileptic fit. The faculty might conceivably be a spiritual gift, but it was a very uncomfortable one which appeared to serve no purpose.

Her nervousness had vanished. The silence was total, which was characteristic. No one coughed, the babies were asleep and the children were quiet. Even the traffic had faded away. August sunshine streamed in an arrested waterfall of light through the windows of the south-nave aisle and the south windows of the clerestory. She knew beyond any doubt that something terrible was going to happen.

The two people Sally loved best in the world were sitting in the second pew from the front, almost directly beneath her. Lucy was sitting on Michael’s lap, frowning up at her mother. On the seat beside her was a book and a small cloth doll named Jimmy. Michael’s head was just above Lucy’s. When you saw their heads so close together, it was impossible to doubt the relationship between them: the resemblance was easy to see and impossible to analyse. Michael had his arms locked around Lucy. He was staring past the pulpit and the nave altar, up the chancel to the old high altar. His face was sad, she thought: why had she not noticed that before?

Sally could not see Derek without turning her head. But she knew he would be staring at her with his light-blue eyes fringed with long sandy lashes. Derek disturbed her because she did not like him. Derek was the vicar, a thin and enviably articulate man with a very pink skin and hair so blond it was almost white.

Most of the other faces were strange to her. They must be wondering why I’m just standing here, Sally thought, though she knew from experience that these moments existed outside time. In a sense, they were all asleep: only she was awake.

The pressure was building up. She wasn’t sure whether it was inside her or outside her; it didn’t matter. She was sweating and the neatly printed notes for her sermon clung to her damp fingers.

As always in these moments, she felt guilty. She stared down at her husband and daughter and thought: if I were spiritually strong enough, I should be able to stop this or to make something constructive out of it. Despair flooded through her.

‘Your will be done,’ she said, or thought she said. ‘Not mine.’

As if the words were a signal, time began to flow once more. A woman stood up towards the back of the church. Sally Appleyard braced herself. Now it was coming, whatever it was, she felt better. Anything was an improvement on waiting.

She stared down the nave. The woman was in her sixties or seventies, small, slight and wearing a grubby beige raincoat which was much too large for her. She clutched a plastic bag in her arms, hugging it against her chest as if it were a baby. On her head was a black beret pulled down over her ears. A ragged fringe of grey, greasy hair stuck out under the rim of the beret. It was a warm day but she looked pinched, grey and cold.

‘She-devil. Blasphemer against Christ. Apostate.’ As she spoke, the woman stared straight at Sally and spittle, visible even at a distance, sprayed from her mouth. The voice was low, monotonous and cultivated. ‘Impious bitch. Whore of Babylon. Daughter of Satan. May God damn you and yours.’

Sally said nothing. She stared at the woman and tried to pray for her. Even those who did not believe in God were willing to blame the shortcomings of their lives on him. God was hard to find so his ministers made convenient substitutes.

The woman’s lips were still moving. Sally tried to blot out the stream of increasingly obscene curses. In the congregation, more and more heads craned towards the back of the church. Some of them belonged to children. It wasn’t right that children should hear this.

She was aware of Michael standing up, passing Lucy to Derek’s wife in the pew in front, and stepping into the aisle. She was aware, too, of Stella walking westwards down the nave towards the woman in the raincoat. Stella was one of the churchwardens, a tall, stately black woman who appeared never to be in a hurry.

Everything Sally saw, even Lucy and Michael, seemed both physically remote and to belong to a lesser order of importance. It impinged on her no more than the flickering images on a television set with the sound turned down. Her mind was focused on the woman in the beret and raincoat, not on her appearance or what she was saying but on the deeper reality beneath. Sally tried with all her might to get through to her. She found herself visualizing a stone wall topped with strands of barbed wire.

Michael and Stella had reached the woman now. Like an obliging child confronted by her parents, she held out her arms, giving one hand to Michael and one to Stella; she closed her mouth at last but her eyes were still on Sally. For an instant Michael, Stella and the woman made a strangely familiar tableau: a scene from a Renaissance painting, perhaps, showing a martyr about to be dragged uncomplainingly to the stake, with her eyes staring past the invisible face of the artist, standing where her accuser would be, to the equally invisible heavenly radiance beyond.

The tableau destroyed itself. Stella scooped up the carrier bag with her free hand. She and Michael drew the woman along the pew and walked with her towards the west door. Their shoes clattered on the bright Victorian tiles and rang on the central-heating gratings. The woman did not struggle but she twisted herself round until she was walking sideways. This allowed her to turn her head as far as she could and continue to stare at Sally.

The heavy oak door opened. The sound of traffic poured into the church. Sally glimpsed sunlit buildings, black railings and a blue sky. The door closed with a dull, rolling boom. For an instant the boom didn’t sound like a closing door at all: it was more like the whirr of great wings beating the air.

Sally took a deep breath. As she exhaled, a picture filled her mind: an angel, stern and heavily feathered, the detail hard and glittering, the wings flexing and rippling. She pushed the picture away.

‘God does not change,’ she said again, her voice grim. ‘But we do.’

Afterwards Derek said, ‘These days we need bouncers, not churchwardens.’

Sally turned to look at him combing his thinning hair in the vestry mirror. ‘Seriously?’

‘We wouldn’t be the first.’ His reflection gave her one of his pastoral smiles. ‘I don’t mean it, of course. But you’ll have to get used to these interruptions. We get all sorts in Kensal Vale. It’s not some snug little suburb.’

This was a dig at Sally’s last parish, a predominantly middle-class enclave in the diocese of St Albans. Derek took a perverse pride in the statistics of Kensal Vale’s suffering.

‘She needs help,’ Sally said.

‘Perhaps. I suspect she’s done this before. There have been similar reports elsewhere in the diocese. Someone with a bee in her bonnet about women in holy orders.’ He slipped the comb into his pocket and turned to face her. ‘Plenty of them around, I’m afraid. We just have to grin and bear it. Or rather them. We get worse interruptions than dotty old ladies, after all – drunks, drug addicts and nutters in all shapes and sizes.’ He smiled, pulling back his lips to reveal teeth so perfect they looked false. ‘Maybe bouncers aren’t such a bad idea after all.’

Sally bit back a reply to the effect that it was a shame they couldn’t do something more constructive. It was early days yet. She had only just started her curacy at St George’s, Kensal Vale. Salaried parish jobs for women deacons were scarce, and she would be a fool to antagonize Derek before her first Sunday was over. Perhaps, too, she was being unfair to him.

She checked her appearance in the mirror. After all this time the dog collar still felt unnatural against her neck. She had wanted what the collar symbolized for so long. Now she wasn’t sure.

Derek was too shrewd a manager to let dislike fester unnecessarily. ‘I liked your sermon. A splendid beginning to your work here. Do you think we should make more of the parallels between feminism and the antislavery movement?’

A few minutes later Sally followed him through the church to the Parish Room, which occupied what had once been the Lady Chapel. Its conversion last year had been largely due to Derek’s gift for indefatigable fund-raising. About thirty people had lingered after the service to drink grey, watery coffee and meet their new curate.

Lucy saw her mother first. She ran across the floor and flung her arms around Sally’s thighs.

‘I wanted you,’ Lucy muttered in an accusing whisper. She was holding her doll Jimmy clamped to her nose, a sign of either tiredness or stress. ‘I wanted you. I didn’t like that nasty old woman.’

Sally patted Lucy’s back. ‘I’m here, darling, I’m here.’

Stella towed Michael towards them. She was in her forties, a good woman, Sally suspected, but one who dealt in certainties and liked the sound of her own voice and the authority her position gave her in the affairs of the parish. Michael looked dazed.

‘We were just talking about you,’ Stella announced with pride, as though the circumstance conferred merit on all concerned. ‘Great sermon.’ She dug a long forefinger into Michael’s ribcage. ‘I hope you’re cooking the Sunday lunch after all that.’

Sally took the coffee which Michael held out to her. ‘What happened to the old woman?’ she asked. ‘Did you find out where she lives?’

Stella shook her head. ‘She just kept telling us to go away and leave her in peace.’

‘Ironic, when you think about it,’ Michael said, apparently addressing his cup.

‘And then a bus came along,’ Stella continued, ‘and she hopped on. Short of putting an armlock on her, there wasn’t much we could do.’

‘She’s not a regular, then?’

‘Never seen her before. Don’t take it to heart. Nothing personal.’

Lucy tugged Sally’s arm, and coffee slopped into the saucer. ‘She should go to prison. She’s a witch.’

‘She’s done nothing bad,’ Sally said. ‘She’s just unhappy. You don’t send people to prison for being unhappy, do you?’

‘Unhappy? Why?’

‘Unhappy?’ Derek Cutter appeared beside Stella and ruffled Lucy’s hair. ‘A young lady like you shouldn’t be unhappy. It’s not allowed.’

Pink and horrified, Lucy squirmed behind her mother.

‘Sally tells me this was once the Lady Chapel,’ Michael said, diverting Derek’s attention from Lucy. ‘Times change.’

‘We were lucky to be able to use the space so constructively. And in keeping with the spirit of the place, too.’ Derek beckoned a middle-aged man, small and sharp-eyed, a balding cherub. ‘Sally, I’d like you to meet Frank Howell. Frank, this is Sally Appleyard, our new curate, and her husband Michael.’

‘Detective Sergeant, isn’t it?’ Howell’s eyes were red-rimmed.

Michael nodded.

‘There’s a piece about your lady wife in the local rag. They mentioned it there.’

Derek coughed. ‘I suppose you could say all of us are professionally nosy in our different ways. Frank’s a freelance journalist.’

Howell was shaking hands with Stella. ‘For my sins, eh?’

‘In fact, Frank was telling me he was wondering whether we at St George’s might form the basis of a feature. The Church of England at work in modern London.’ Derek’s nose twitched. ‘Old wine in new bottles, one might say.’

‘Amazing, when you think about it.’ Howell grinned at them. ‘Here we are, in an increasingly godless society, but Joe Public just can’t get enough of the good old C of E.’

‘I don’t know if I’d agree with you there, Frank.’ Derek flashed his teeth in a conciliatory smile. ‘Sometimes I think we are not as godless as some of us like to think. Attendance figures are actually increasing – I can find you the statistic, if you want. You have to hand it to the Evangelicals, they have turned the tide. Of course, at St George’s we try to have something for everyone – a broad, non-sectarian approach. We see ourselves as –’

‘You’re doing a fine job, all right.’ Howell kept his eyes on Sally. ‘But at the end of the day, what sells a feature is human interest. It’s the people who count, eh? So maybe we could have a chat sometime.’ He glanced round the little circle of faces. ‘With all of you, that is.’

‘Delighted,’ Derek replied for them all. ‘I –’

‘Good. I’ll give you a ring then, set something up.’ Howell glanced at his watch. ‘Good Lord – is that the time? Must love you and leave you.’

Derek watched him go. ‘Frank was very helpful over the conversion of the Lady Chapel,’ he murmured to Sally, patting her arm. ‘He did a piece on the opening ceremony. We had the bishop, you know.’ Suddenly he stood on tiptoe, and waved vigorously at his wife. ‘There’s Margaret – I know she wanted a word with you, Sally. I think she may have found you a baby-sitter. She’s not one of ours, but a lovely woman, all the same. Utterly reliable, too. Her name’s Carla Vaughan.’

On the way home to Hercules Road, Michael and Sally conducted an argument in whispers in the front of the car while Lucy, strapped into the back seat, sang along with ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ on the stereo. It was not so much an argument as a quarrel with gloves on.

‘Aren’t we going rather fast?’ Sally asked.

‘I didn’t realize we were going to be so late.’

‘Nor did I. The service took longer than I expected, and –’

‘I’m worried about lunch. I left it on quite high.’

Sally remembered all the meals which had been spoiled because Michael’s job had made him late. She counted to five to keep her temper in check.

‘This Carla woman, Sal – the child minder.’

‘What about her?’

‘I wish we knew a bit more.’

‘She sounds fine to me. Anyway, I’ll see her before we decide.’

‘I wish –’

‘You wish what?’

He accelerated through changing traffic lights. ‘I wish she wasn’t necessary.’

‘We’ve been through all this, haven’t we?’

‘I suppose I thought your job might be more flexible.’

‘Well, it’s not. I’m sorry but there it is.’

He reacted to her tone as much as to her words. ‘What about Lucy?’

‘She’s your daughter too.’ Sally began to count to ten.

‘I know. And I know we agreed right from the start we both wanted to work. But –’

Sally reached eight before her control snapped. ‘You’d like me to be something sensible like a teacher, wouldn’t you? Something safe, something that wouldn’t embarrass you. Something that would fit in with having children. Or better still, you’d like me to be just a wife and mother.’

‘A child needs her parents. That’s all I’m saying.’

‘This child has two parents. If you’re so concerned –’

‘And what’s going to happen when she’s older? Do you want her to be a latchkey kid?’

‘I’ve got a job to do, and so have you. Other people manage.’

‘Do they?’

Sally glanced in the mirror at the back of the sun visor. Lucy was still singing along with a robust indifference to the tune, but she had Jimmy pushed against her cheek; she sensed that her parents were arguing.

‘Listen, Michael. Being ordained is a vocation. It’s not something I can just ignore.’

He did not reply, which fuelled her worst fears. He used silence as a weapon of offence.

‘Anyway, we talked about all this before we married. I know the reality is harder than we thought. But we agreed. Remember?’

His hands tightened on the steering wheel. ‘That was different. That was before we had Lucy. You’re always tired now.’

Too tired for sex, among other things: another reason for guilt. At first they had made a joke of it, but even the best jokes wore thin with repetition.

‘That’s not the point.’

‘Of course it’s the point, love,’ he said. ‘You’re trying to do too much.’

There was another silence. ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ gave way to ‘The Wheels on the Bus’. Lucy kicked out the rhythm on the back of Sally’s seat, attention-seeking behaviour. This should have been a time of celebration after Sally’s first service at St George’s. Now she wondered whether she was fit to be in orders at all.

‘You’d rather I wasn’t ordained,’ Sally said to Michael, voicing a fear rather than a fact. ‘In your heart of hearts, you think women clergy are unnatural.’

‘I never said that.’

‘You don’t need to say it. You’re just the same as Uncle David. Go on, admit it.’

He stared at the road ahead and pushed the car over the speed limit. Mentioning Uncle David had been a mistake. Mentioning Uncle David was always a mistake.

‘Come on.’ Sally would have liked to shake him.

‘Talk to me.’

They finished the journey in silence. In an effort to use the time constructively, Sally tried to pray for the old woman who had cursed her. She felt as if her prayers were falling into a dark vacuum.

‘Your will be done,’ she said again and again in the silence of her mind; and the words were merely sounds emptied of meaning. It was as if she were talking into a telephone and not knowing whether the person on the other end was listening or even there at all. She tried to persuade herself that this was due to the stress of the moment. Soon the stress would pass, she told herself, and normal telephonic reception would be restored. It would be childish to suppose that the problem was caused by the old woman’s curse.

‘Shit,’ said Michael, as they turned into Hercules Road. Someone had usurped their parking space.

‘It’s all right,’ Sally said, hoping that Lucy had not heard. ‘There’s a space further up.’

Michael reversed the Rover into it, jolting the nearside rear wheel against the kerb. He waited on the pavement, jingling his keys, while Sally extracted Lucy and her belongings.

‘What’s for lunch?’ Lucy demanded. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘Ask your father.’

‘A sort of lamb casserole with haricot beans.’ Michael tended to cook what he liked to eat.

‘Yuk. Can I have Frosties instead?’

Their flat was in a small, purpose-built block dating from the 1930s. Michael had bought it before their marriage. It was spacious for one person, comfortable for two and just large enough to accommodate a small child as well. As Sally opened the front door, the smell of burning rushed out to greet them.

‘Shit,’ Michael said. ‘And double shit.’

Before Lucy was born, Sally and Michael Appleyard had decided that they would not allow any children they might have to disrupt their lives. They had seen how the arrival of children had affected the lives of friends, usually, it seemed, for the worse. They themselves were determined to avoid the trap.

They had met through Michael’s job, almost six years before Sally was offered the Kensal Vale curacy. Michael had arrested a garage owner who specialized in selling stolen cars. Sally, who had recently been ordained as a deacon, knew his wife through church and had responded to a desperate phone call from her. The apparent urgency was such that she came as she was, in gardening clothes, with very little make-up and without a dog collar.

‘It’s a mistake,’ the woman wailed, tears streaking her carefully made-up face, ‘some ghastly mistake. Or someone’s fitted him up. Why can’t the police understand?’

While the woman alternately wept and raged, Michael and another officer had searched the house. It was Sally who dealt with the children, talked to the solicitor and held the woman’s hand while they asked her questions she couldn’t or wouldn’t answer. At the time she took little notice of Michael except to think that he carried out a difficult job with more sensitivity than she would have expected.

Three evenings later, Michael arrived out of the blue at Sally’s flat. On this occasion she was wearing her dog collar. Ostensibly he wanted to see if she had an address for the wife, who had disappeared. On impulse she asked him in and offered him coffee. At this second meeting she looked at him as an individual and on the whole liked what she saw: a thin face with dark eyes and a fair complexion; the sort of brown hair that once had been blond; medium height, broad shoulders and slim hips. When she came into the sitting room with the coffee she found him in front of the bookcase. He did not comment directly on its contents or on the crucifix which hung on the wall above.