Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

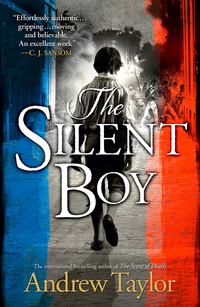

Kitabı oku: «The Silent Boy»

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 2014

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Cover photographs © Julian Elliott / Getty Images (street);

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy (back); Henry Steadman (boy)

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical fact, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007506576

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2014 ISBN: 9780008132781

Version: 2017-05-10

Dedication

For James

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

About the Author

By the same author

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Say nothing. Not a word to anyone. Whatever you see. Whatever you hear. Do you understand? Say nothing. Ever.

Tip-tap. Like cracking a walnut.

Now and always Charles sees the blood. It runs down his cheek and soaks into his shirt. He licks his dry lips and tastes it, salty and metallic and forbidden.

He has fallen as he ran down the steep stairs. He’s lying on his back. He looks up. It is raining blood from a black sky striped with yellow. Blood glistens in the light of the lantern on the table.

There’s shouting and banging outside.

Inside, the blood is crying out. It’s screaming and shouting and grunting. The sound twists through his skull. It cuts into bone and splinters into a thousand daggers that draw more blood.

He scrambles to his feet. His shoes are by the door. He slips his feet into them.

There are no words for this, all he has heard and seen. There are no words for anything. There must never be any words.

Awake and asleep, here and anywhere, now and always. Never any words.

Charles lifts the latch and drags open the heavy door. No more words.

Hush now. Say nothing.

Tip-tap.

Charles darts out of the cottage and pulls the door shut. The cobbled yard is in darkness. So are the workshops and the big house beyond. Above the rooftops, though, the air flickers orange and yellow with the light of torches. The noise is deafening. He wants to cover his ears.

The tocsin is ringing. There are other bells. Their jangling fills the night and mingles with the host of unnatural sounds. The street on the far side of the house is as noisy as by day – much noisier, with shouts and screams, with barks and explosions, with the clatter of hooves and the grating of iron-rimmed wheels.

Someone begins to knock at a door – not with a hand or a knocker. These blows are slow and purposeful. They make the air itself tremble. Glass shatters. Someone is shrieking.

Wood splinters. They are breaking down the door of the main house. In a matter of minutes they will be in the yard.

Charles stumbles towards the big gates beyond the cottage. Two heavy bars hold them shut, sealing the back of the yard. In one leaf is a little low wicket.

At night the wicket is secured by two bolts. He fumbles for them in the darkness, only to find that they are already open.

Of course they are.

He pushes the gate outward. Nothing happens. Locked, not bolted? In desperation he tugs it towards him. The gate slams into him with such force that he falls on the slippery cobbles.

The cottage door is opening.

Panic surges through him. He is on his feet again. The lane outside the gate is in darkness. He leaps through the wicket. The lane beyond runs parallel to the street. The warm air stinks of decay. The city is so hot it has gone mad.

In the confusion, he is dimly aware that the hammering from the house has stopped. There are lights on the other side of the yard. Shutters are flung open. The windows fill with the light of hell.

Chains rattle, bolts slide back. A dog is barking with deep, excited bellows.

Through the open wicket he sees the house door opening. He glimpses the black shape of a huge dog in the doorway.

Charles covers his mouth with his hand to keep the words inside from spilling out. He turns and runs.

There is so much confusion in the world that no one gives Charles a second glance. They push past him. They cuff him out of their way as if swatting a fly.

He is of no interest to them. He is nothing. He is glad to be nothing. He wants to be less than nothing.

He shrinks back into a doorway. He sees blood everywhere, in the gutters, on the faces and clothes of the men and women hurrying past him, daubed on the wall opposite.

At the corner of the street, the crowd has surrounded a coach. They are pulling out the man and the woman inside and throwing out their possessions. A hatbox falls open and the hat rolls out. A man stamps on it.

The woman is crying, great ragged sobs. The gentleman is quite silent. His eyes are closed.

The baker’s assistant, who is a burly fellow half a head taller than everyone else, tugs at the woman’s dress. He paws at the neck. The thin fabric rips.

Charles slips from the doorway. He does not know where he is going but his feet know the way. He has nothing with him except the shirt he was sleeping in, his breeches and the shoes on his feet.

The sign of the Golden Pheasant hangs above the shop that sells poultry. Someone has draped a petticoat over it.

Old Barbon, the porter of the house five doors down, is lying on the ground. He is pouring wine into his mouth and the liquid runs over his cheeks. Barbon once gave him a plum so sweet and juicy that Marie said it came from the angels.

Madame Pial, who keeps the wine shop in the next street, is dragging a sack along the road. She has lost her hat and her cap. Her grey hair flows in a greasy tide over her shoulders.

The Rue de Richelieu is seething with people. Their faces are twisted out of shape. They are no longer human. They are ghouls in a nightmare. Charles pushes through them in the direction of the river. The street ends at the Rue Saint-Honoré. He means to turn left and cross the river at the Pont Royal. But the crowd is even denser here, clustering around the Tuileries like wasps round a saucer of jam. He will not be able to force his way through.

Besides, lying on the road not three yards away from him is one of the King’s Swiss Guards. The man has no head and he has lost his boots and breeches. His entrails coil out of his belly, gleaming in the torchlight, still twitching.

Charles slows. He weaves eastwards towards the Île du Palais. He crosses the river at the Pont Neuf. National Guards are on both sides of the river and also on the Île du Palais itself. But they are taking no notice of the people who stream north over the river towards the Tuileries. He slips among them, against the flow of the tide. He smells sweat and excitement and anger.

There are fewer people on the Rive Gauche. But the noise is almost as bad. The sound of artillery and musket fire near the Tuileries. The screams and shouts. The clatter of wheels and hooves.

On the Quai d’Orsay and the Quai Theatines people are watching the battle on the other side of the river as if it is a firework display.

In the Rue Dauphine, his mind clears, not much but enough to realize where he is going. He has been here only once before, and then it was daylight and everything was normal. It takes him nearly an hour to find his way, casting to and fro in the near darkness, avoiding the crowds, avoiding the people who try to sweep him into their lives.

At last, not far from the Café Corazza, he stumbles on the narrow mouth of the alley. It leads to a paved court. The only light comes from an oil lamp on a second-floor windowsill. The lamp casts a faint dirty-yellow fragrance. The court has trapped the sun’s warmth during the day. It is even hotter than the street.

For a moment he listens. He hears nothing nearby except the scramble of rats, a sound grown so familiar he barely notices it.

He finds the door with the help of his fingertips not his eyes.

The wood is old and scarred and as dry as a desert. Charles hammers on it until his knuckles bleed. He hammers on it until it opens.

Marie is not much taller than he is. She is almost as wide as she is tall. She looks like a bull in a faded blue dress and carries with her a smell of sweat, garlic and woodsmoke, mingled with a sour, milky quality that is hers alone. Her smell is as familiar to Charles as anything in the world.

She draws him over the threshold and squeezes him in her arms so tightly that he finds it hard to breathe.

‘What happened?’ she says. ‘Where is Madame?’

She asks him questions over and over again and he cannot answer any of them. In the end she gives up. She brings water and a cloth and rinses the blood from his face and hands.

The only light in the room comes from the stump of a tallow candle and a rushlight on the unlit stove. That is why she does not see the clotted patches of blood in his hair. But her fingers find them. She makes the smacking noise with her lips that signifies her disapproval of something. With sudden violence, she strips off his breeches and his stained shirt. She drags him, white and naked, into the court.

There is a pump in one corner. She holds him under it with one hand and sluices water over him with the other. She runs her fingers through his wet hair, over every surface and into every crack and cranny of his slippery body. She rinses him again. With a hand on his neck, she pushes him in front of her into the room and bars the door behind them.

Despite the heat, Charles is shivering. She wraps him in a blanket, makes him sit on a stool and lean against the wall. She brings him water in a beaker made of wood.

He drinks greedily. She is humming quietly. She often does this, the same three notes, la-la-la, low and soft, over and over again.

He is glad that Luc is not there. Luc is Marie’s brother. He is a kitchen porter. He has only one eye, owing to a frightful accident in the slaughterhouse where he used to work. Though she did not witness it herself, Marie has described the accident to him many many times in graphic detail.

Charles’s one visit to this house, nearly a year ago, was so that he might see in person the angry red crater that was the site of Luc’s lost left eye. It was not as impressive in reality as in imagination. For the sake of his hosts, he acted out a polite pantomime of shock and horror. In truth, however, he was disappointed.

When Marie took him home again, he left a sou on the stove, because he knew that she and Luc were poor. Marie was Charles’s nurse when he was very young and later stayed as a maid. But then she was dismissed and the boy cried himself to sleep for nearly a week.

Now the brother and sister live in one room. Their bed is in a curtained alcove by the stove.

When Charles has had all the water he can drink, she brings in the chamber pot and watches him urinate. Afterwards she makes him kneel by the bed. She kneels beside him and says the prayer to the Virgin that she always says before he goes to sleep.

He knows that he is meant to join in. When he does not, she looks sharply at him and pokes him in the ribs. When she begins the prayer again, he moves his lips, mouthing shapes which have no words to them.

She watches him closely but does not seem to mind. Perhaps she does not know the difference between words that have shapes and words that do not.

Marie puts him into bed, blows out the candle and climbs in beside him. The mattress sinks beneath her weight. His body has no choice but to sink towards her and to mould its contours to hers.

It is very hot and it grows hotter. Now he is big he does not care for the way she smells or the way she looms over him like a mountain of flesh.

Soon she drifts into sleep. She snores and twitches.

The snoring stops. ‘Tell me,’ she whispers. ‘What happened? Where is Madame?’

He does not answer. He must never answer. Say nothing. Not a word.

Marie prods him again with her finger. ‘What happened?’

Tip-tap. Like cracking a walnut.

When he does not answer, she sighs noisily and turns her head away.

He listens to her breathing. He closes his eyes but then he sees what he does not wish to see. He opens them again and stares into the night.

Luc does not come back for three days. When he does, he is drunk with blood and brandy. The single eye is bloodshot.

He does not see the boy at first. He calls for wine. He calls for food. Marie tries to press her brother into the chair but he resists.

Charles is in the alcove, in the bed. He rolls a little to the left, hoping to conceal himself behind the half-drawn curtains. But Luc’s single eye catches the movement.

‘What the devil is that?’ he says in a voice so hoarse he can barely raise it above a whisper.

‘Madame von Streicher’s boy. He came the other night.’

‘Who brought him?’

‘No one.’

Luc advances towards the alcove and stares at Charles, who looks back at him because he doesn’t know what else to do.

‘Where’s your mother?’ Luc demands.

The boy says nothing.

‘I don’t know,’ Marie says. ‘He was covered with blood.’

‘Take him back. We don’t want him here.’

‘I tried,’ Marie says. ‘I sent a message to the Rue de Grenelle but Madame isn’t there any more. The concierge said she and the boy moved out a month ago.’

‘They are traitors,’ Luc says suddenly. ‘She’s been arrested. If we shelter him, they’ll arrest us too. You know where that ends.’ Luc makes a blade of his right hand and chops it down on the palm of his left.

He means the guillotine. Charles has heard his mother and Dr Gohlis talking about the machine, and Dr Gohlis said that it is a humane way to execute criminals. But, he said, the people do not like it because it is too swift and too clean a way to die. They prefer the old ways – hanging on wooden gallows, or death by sword or breaking on the wheel. They last longer, Dr Gohlis said, and they are more entertaining.

‘They’ve set up the machine at the Tuileries now. At the Place du Carrousel.’

Marie pours her brother wine. She stands, hands on hips, in front of the alcove, with the boy behind her.

Luc takes a long swallow of wine and wipes his mouth on the back of his hand. ‘Throw him out. In the gutter. Anywhere.’

‘I can’t. He’s only a child.’

‘If they find out he’s here, it’ll be enough to bring us before the Tribunal.’

‘But he couldn’t hurt a—’

Luc throws the beaker of wine at his sister, catching her on the face. She gives a cry and turns. Charles sees the blood on her cheek.

‘You will do as I say,’ Luc says. ‘Or I’ll break every bone in his body, and in yours.’

Chapter Two

Marie holds tightly to Charles’s arm. She pulls him from the shadowy, urine-scented safety of the alleyway leading to the court and into the crowded street.

She tugs him along, jerking his arm to hurry him up. He is a fish on a line, pulled through a river of people.

It is the first time he has been outside since the night he came to Marie’s. Everything is brighter, louder and noisier than it should be – the clothes, the cockades, the soldiers, the checkpoints, the swaying, seething parties of men and women. There is urgency in the air, an invisible miasma that touches everyone. He wants to be part of it.

Before they came out, Marie combed his hair. He is wearing his shirt and breeches, which she washed the day before, though her best efforts could not remove all the blood from them. They do not go north towards the river but west. They pass Saint-Sulpice and turn into the Rue du Bac.

Marie drags him across the street, threading their way through the coaches and wagons by force of personality and a steady stream of oaths. She stops outside a great house with black gates, studded with iron.

The black gates are shut. Marie mutters under her breath and tugs on the bell handle with her free hand. She does not let go of Charles with the other hand. She grips his wrist so tightly he fears it will snap.

The bell clangs on the other side of the gates but no one comes. Marie bounces up and down on her little feet. She rings the bell again. A passer-by jostles Charles, wrenching him from Marie’s grasp. He sprawls in the gutter and grazes his knees. Marie swears at the man and hauls him to his feet. She pulls the bell a third time, for longer and harder than before.

A shutter slides back in the wicket. A man’s eyes and nose are revealed in the small rectangle.

‘The house is shut up,’ he says. ‘Go away.’

‘Where’s Monsieur the Count?’ Marie demands.

‘Gone. All gone.’

The shutter slams home. Marie rings the bell again. She hammers on the door. Nothing happens.

She knocks again. By now a crowd has gathered, watchful and silent.

Marie turns from the gates and asks the bystanders what they think they’re staring at. Such is the force of her authority, of her anger, that they drift away, shamefaced.

Muttering under her breath, Marie leads Charles away from the gates in the direction of the Grand École. He starts to cry.

A slim gentleman is coming towards them on foot. His left leg drags behind him. He is dressed plainly in a dark green coat. Charles recognizes him and so does Marie.

She leaps forward into the man’s path and pushes the boy in front of her. ‘Monseigneur!’ she cries. ‘Monseigneur!’

He stops, frowning, his face suddenly wary. ‘Hush, hush – I am plain Monsieur Fournier now. You know that.’

‘Monsieur, you came to Madame von Streicher’s.’

He frowns at Marie. ‘I am sorry. There is nothing I can do for you. Whoever you are.’

‘Monsieur.’ She shoves the boy forward, so forcefully that he bumps against Monsieur Fournier’s arm. ‘This is Madame’s son. This is Charles. You must remember him.’

Monsieur Fournier has large brown eyes that open very wide as if life is a matter of endless astonishment to him.

‘This?’

‘Yes, monsieur, I swear it. On my life.’

Fournier motions them to move to one side with him. They stand by the outer wall of the great house. The passers-by ebb around them.

Fournier takes Charles’s chin in his hand and angles it upwards. ‘Yes, by God, you’re right.’ He bends closer, bringing his head almost on a level with the boy’s. ‘What happened? Are you hurt?’

Charles says nothing.

‘He won’t speak, monsieur,’ Marie says.

‘Of course he can speak.’ Monsieur Fournier touches Charles’s shoulder with a long white forefinger. ‘You know me, don’t you?’

‘He won’t say anything, monsieur. Not since that night.’

‘Are you saying he was actually there? When …?’ His voice tails away, rising into an unspoken question.

‘Have you seen Madame?’ Marie says. ‘Is she …?’ She runs out of words, too.

Fournier looks at her. ‘You weren’t there yourself?’

‘No, monsieur. I was at my – my brother’s house. Charles came to me in the night. He was …’

‘He was what?’ demands Fournier.

‘There was blood all over him.’ She paws at the faded stains on Charles’s shirt. ‘See? Everywhere. On his clothes, in his hair.’

‘Dear God.’

Her voice rises. ‘He won’t even tell me what happened. He won’t tell me anything. I can’t keep him at home. My brother will throw him out.’

‘You did well to bring him.’ Monsieur Fournier takes out a handkerchief and wipes his face. ‘We can’t talk here. Follow me.’

He sets off in the direction he came from, walking so rapidly despite his limp that Charles and Marie have to break into a trot to keep up. He takes the next turning, a lane running along the side of the house. There are no windows on the ground floor, only small ones high up in the wall, far above Charles’s head. These windows are protected by heavy grilles of iron bars, painted black like the gates.

They turn another corner into a narrow street parallel to the Rue du Bac. Here is another, much smaller gate set in the wall of the house.

Monsieur Fournier looks up and down the lane. There is no one else about. He knocks twice on the gate, pauses, knocks once, pauses again and then knocks twice again.

The shutter slides back. Nobody speaks. On the other side of the gate there is a rattling of bars. The key turns. The gate opens – not to its full extent, merely enough to allow a man to pass through.

Fournier is the first to enter. Marie pushes the boy after him. As she does so she ruffles his hair.

They are in a cobbled yard with a well in one corner. A fat old man in a dirty brown coat stares open-mouthed at them. Fournier limps towards the great grey cliff of the house. The old man jerks with his head towards the house, which means that Charles must follow.

Charles breaks into a run. Behind him, he hears the gate closing.

It is only when he is inside the house, when he is following Monsieur Fournier up a long flight of stone stairs that he realizes Marie is no longer there. She has stayed on the other side of the black gate.

The room is almost as large as a church. Despite the sunshine outside, it is gloomy, for the shutters are still across the windows. Light filters through the cracks. One of the shutters is slightly open and a bar of sunlight streams across the carpet to a huge desk.

The desk is made of a dark wood ornamented with gold which sparkles in the sunshine. Its top is as big as his mother’s bed and it has many drawers. It is covered in papers – some in piles, some lying loose as if blown by a gust of wind.

Behind the desk, facing into the room, is a stout gentleman whose face is in shadow. He looks up as Monsieur Fournier enters, and Charles recognizes him.

‘I thought you’d be halfway to—’ The gentleman sees Charles behind Monsieur Fournier. He breaks off what he is saying.

‘This is more important,’ Fournier says.

‘What the devil do you want with that boy?’

Fournier advances into the room with Charles trailing behind him. One of the piles of paper is weighted down with a pistol. Charles wishes that he were back with Marie, lying in her bed against her great flank and smelling her strange, unlovely smell.

‘You don’t understand. He’s Madame von Streicher’s son.’

Charles knows that this man is very important. He is Count de Quillon, the owner of this house, the Hotel de Quillon, and so much else. The Minister, Maman says, the godson of the King and once the King’s friend. He sometimes came to see Maman, though more often he would send a servant with a message and Maman would put on one of her best gowns and go away in his great coach.

Only now, when the Count rests his elbows on the desk, does the sunlight bring his face alive. He is a broad, heavy man, older than Fournier, with a small chin, a big nose and a high complexion.

‘This is Augusta’s son?’ the Count says. ‘This? Are you sure? Absolutely sure?’

‘Quite sure, despite the dirt and the rags.’

‘How does he come here?’

‘He ran away and went to an old servant’s. She brought him a moment ago.’

‘So was he with his mother when—’

Fournier interrupts: ‘I don’t know. He was covered in blood when he turned up at the old woman’s house.’

‘It is of the first importance that we discover what happened. Where is the servant? She must know something.’

‘She ran off as soon as we came through the gate.’

The men are talking as if Charles is not there. He might be invisible. Or he might not even exist at all. He cannot grasp this idea. Nevertheless, part of him quite likes it.

‘Come here, boy,’ says the Count.

Charles steps up to the desk. He makes himself stand very straight.

‘What happened at your house that night? The – the night you ran away?’

Charles does not speak.

‘Don’t be shy. I can’t abide a timid boy. Answer me. Who else was there? I must know.’

‘The woman said he simply won’t speak,’ says Fournier. ‘No reason why he shouldn’t, of course – he’s perfectly capable of it. I remember him chattering away ten to the dozen.’

‘Answer me!’ the Count roared, rearing up in his chair. ‘You will answer me.’

Tears run down Charles’s cheeks. He says nothing.

Fournier shifts his weight from his left leg. ‘Give the lad time to get his bearings,’ he suggests. ‘Gohlis can see him.’

‘We don’t have time for all that,’ the Count says. He adds rather petulantly, ‘Anyway, he’s not some lad or other – his name is Charles. I should know.’ He beckons Charles closer and studies the boy’s face. ‘Were you there? Did you see what happened to—’

‘My friend, I think this—’

The Count waves Fournier away. ‘Did you see what happened to your mother? Did you see who came?’

Charles stares at the pistol on the pile of papers. Is it loaded? If you cocked it and put it to your head and pulled the trigger, then would everything stop, just like that? Everything, including himself?

‘It is most important that you tell us,’ the Count says, raising his voice. ‘A matter of life and death. Answer me, Charles. Who was there?’

But Charles is still thinking about the pistol. If he shot himself, would St Peter take one look at him and send him down to the fires of hell? Or would there simply be nothing at all, a great emptiness with no people in it, living or dead?

‘Oh for God’s sake!’ the Count snaps.

The boy recoils as if he has been slapped.

‘Very well, then.’ The Count tugs the bell pull behind him. ‘We’ll talk to him when he’s past his absurd shyness. Someone will look after him and give him some food.’

Fournier rests a hand on Charles’s shoulder. ‘But what about later? If we leave?’

‘Then he comes with us.’ Monsieur de Quillon bends his great head over his papers. ‘Naturally.’