Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Knitting Circle: The uplifting and heartwarming novel you need to read this year»

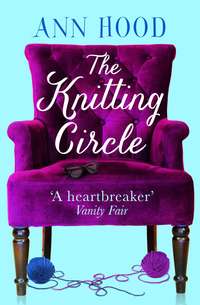

ANN HOOD

The Knitting Circle

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers in 2008

This ebook edition published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2017

Copyright © Ann Hood 2008

Cover layout design © debbieclementdesign.com 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Ann Hood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781847560100

Ebook Edition © September 2008 ISBN: 9780007281848

Version: 2017-08-30

Dedication

For knitters

For friends

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One: Casting On

Chapter One: Mary

Chapter Two: The Knitting Circle

Part Two: K2, P2

Chapter Three: Scarlet

Chapter Four: The Knitting Circle

Part Three: Knit Two Together (K2Tog)

Chapter Five: Lulu

Chapter Six: The Knitting Circle

Part Four: Socks

Chapter Seven: Ellen

Chapter Eight: The Knitting Circle

Part Five: A Good Knitter

Chapter Nine: Harriet

Chapter Ten: The Knitting Circle

Part Six: Sit And Knit

Chapter Eleven: Alice

Chapter Twelve: The Knitting Circle

Part Seven: Mothers And Children

Chapter Thirteen: Beth

Chapter Fourteen: The Knitting Circle

Part Eight: Knitting

Chapter Fifteen: Roger

Chapter Sixteen: The Knitting Circle

Part Nine: Common Suffering

Chapter Seventeen: Mamie

Chapter Eighteen: The Knitting Circle

Part Ten: Casting Off

Chapter Nineteen: Mary

Chapter Twenty: The Knitting Circle

Acknowledgments

The Knitting Circle

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

Daughter, I have a story to tell you. I have wanted to tell it to you for a very long time. But unlike Babar or Eloise or any of the other stories that you loved to hear, this one is not funny. This one is not clever. It is simply true. It is my story, yet I do not have the words to tell it. Instead, I pick up my needles and I knit. Every stitch is a letter. A row spells out “I love you.” I knit “I love you” into everything I make. Like a prayer, or a wish, I send it out to you, hoping you can hear me. Hoping, daughter, that the story I am knitting reaches you somehow. Hoping, that my love reaches you somehow.

PART ONE

Casting On

To knit, you have to have the stitches on one needle. ‘Casting on’ is the term for making the foundation row of stitches. Once you have cast on, you are ready to knit. —NANCY J. THOMAS AND ILANA RABINOWITZ, A Passion for Knitting

1

Mary

Mary showed up empty-handed.

“I don’t have anything with me,” she said, and she opened her arms to indicate their emptiness.

The woman standing before her was called Big Alice, but there was nothing big about her. She stood five feet tall, with a tiny waist, short silver hair, and gray eyes the color of a sky right before a storm. Big Alice had her slight body wedged between the worn wooden door to the shop and Mary herself.

“This isn’t really my kind of thing,” Mary said apologetically.

The woman nodded. “I know,” she said, stepping back so that the door swung open wide. “I can’t tell you how many people have stood right where you’re standing and said that exact thing.” Her voice was soft, British.

“Well,” Mary said, because she didn’t know what else to say.

She never did know what to say these days, or what to do. This was in September, five months after her daughter Stella had died. That stunned disbelief had ebbed slightly, but the horrible noises in her head had grown. They were hospital noises, doctors’ voices, and Stella’s own five-year-old voice saying Mama. Sometimes Mary imagined she really heard her daughter calling out to her and her heart would squeeze tight on itself.

“Come on in,” Big Alice said.

Mary followed her into the shop. Alice wore a gray tweed skirt, a white oxford shirt, a gold cardigan, and pearls. Although the top half of her looked like a schoolmarm, she had crazy-colored striped socks on her feet and pink chenille bedroom slippers with red rhinestone cherries across the tops.

“I’ve got the gout,” Big Alice explained, lifting one slippered foot. Then she added, “I guess you know I’m Alice.”

“Yes,” Mary said.

Like everything else, Mary could easily have forgotten the woman’s name. She’d written it on one of the hundreds of Post-its scattered around the house like confetti after a party. But, like all of the phone numbers and dates and directions, the paper with Alice written on it was gone. Outside the store, however, a wooden sign read Big Alice’s Sit and Knit, and when Mary saw it she had remembered: Alice.

Mary stopped and got her bearings. These days this was always necessary, even in familiar places. In her own kitchen she would stop what she was doing and look around, take stock. Oh, she would say to herself, noting that the television was off instead of tuned to Sagwa, the Chinese Cat; the bowl Stella had made at Claytime with its carefully painted and placed polka dots was empty of the sliced cucumbers or mound of blueberries it used to hold; the cutout hearts with crayoned I love you’s and the construction-paper kite with its pink ribbon tail drooped. Oh, Mary would say, realizing all over again that this was how her kitchen—her life—looked now. Empty and sad.

The shop was small, with creaky wooden floors and baskets and shelves brimming over with yarn. It smelled like sweaters and cedar and Alice’s own citrus scent. There were three rooms: this small one, the room beyond with the cash register and a well-worn couch slipcovered in a pink and red floral pattern, and another larger room with more yarn and a few chairs.

The yarn was beautiful. Mary saw this immediately and touched some as she followed Alice into the next room, letting her fingertips linger a bit over the skeins.

“So,” Alice was saying, “we’ll start you on a scarf.” She held up a finished scarf. Cobalt blue with pale blue tassels. “You like this one?”

“I guess so,” Mary said.

“You don’t like it? You’re frowning.”

“I do. It’s fine. It’s just, I can’t make it. I’m not good with my hands. I flunked home ec. Really, I did.”

Alice turned toward the wall and pulled down some wooden knitting needles.

“A ten-year-old can make that scarf,” she said, a bit impatiently. She handed the needles to Mary.

They felt large and smooth and awkward in her hands. Mary watched as Alice went over to a shelf and grabbed several balls of yarn. The same cobalt blue, and aquamarine, and mauve.

“Which color do you like?” Alice said. She held them out to Mary like an offering.

“The blue, I guess,” Mary said, and the particular blue of Stella’s eyes presented itself in her mind. When she tried to blink it away, she felt tears slide out. She turned her head and wiped her eyes.

“Blue it is,” Alice said, more gently. She pointed to a chair tucked into a corner beneath balls of fat yarn. “Sit down and I’ll teach you how to knit.”

Mary laughed. “Such optimism,” she said.

“A woman came in here two weeks ago,” Alice said, dropping into an overstuffed chair and sticking her feet up on a small footstool with a needlepoint cover. “She’d never knit a thing, and she’s made three of these scarves. That’s how easy it is.”

Mary had driven forty miles to this store, even though there was a knitting shop less than a mile from her house. As she navigated the unfamiliar back roads, it had seemed foolish, coming so far, to knit of all things. But sitting here with this stranger who knew nothing about her, or about what had happened, with these unfamiliar needles in her sweaty hands, Mary knew somehow that it was the right thing to do.

“It’s just a series of slipknots,” Alice said. She held up a long tail of the yarn and demonstrated.

“I was kicked out of the Girl Scouts,” Mary said. “Slipknots are a mystery to me.”

“First home economics. Then the Girl Scouts,” Alice said, tsking. But her gray eyes gleamed mischievously.

“Actually, it was Girl Scouts, then home ec,” Mary said.

Alice chuckled. “If it makes you feel any better, I hated knitting. Didn’t want to learn. Now here I am. I own a knitting store. I teach people to knit.”

Mary smiled politely. Other people’s stories held little interest for her. She used to like to listen to tales of broken hearts and triumphs and the odd twists of life. But her own story had taken over the part of her that was once open to such things. And if she listened out of politeness or necessity—like now—the situation begged for her to talk, to share. She wanted no part in that. There were times when she wondered if she’d ever tell her story to anyone.

“So,” Mary said, “slipknots.”

“Since you’re a Girl Scouts–home economics flunkee,” Alice said, “I’ll cast on for you. Besides, if I stand here and teach you, I’ll be wasting both our time because you’re going to forget.”

Mary didn’t bother to ask what “cast on” meant. Like a magician practicing sleight of hand, Alice made a series of loops and twists, then held out one needle, the blue yarn snaking up it ominously.

“I cast on twenty-two stitches for you, and you’re ready to go.”

“Uh-huh,” Mary said.

Alice motioned for Mary to come sit beside her.

“In here,” Alice said, demonstrating. “Then wrap the yarn like this. And pull this needle through.”

Mary smiled as first one stitch, then another, appeared on the empty needle.

“Okay,” Alice said. “Go ahead.”

“Me?” Mary said.

“I already know how to do it,” Alice said, “don’t I?”

Mary took a breath and began.

2

The Knitting Circle

Here was what Mary still found extraordinary: on the day before Stella died, nothing unusual happened. There were no signs, no premonitions, nothing but the simple daily routine of their life together—she and Dylan and Stella. Her neighbor when she’d lived in San Francisco, on a high hill in North Beach, had been an old Italian woman named Angelina. Angelina always wore a black shawl over her head, and thick-soled black shoes, and a black dress. “People should know you’re in mourning,” she’d told Mary. “When you wear black, they understand.”

Mary hadn’t pointed out to her that everyone wore black these days. She hadn’t rolled her eyes or smirked when Angelina told her that three days before her husband died—and here she’d made the sign of the cross, spitting into her palm at the end— a dog had howled, facing their apartment. “I knew death was coming,” she’d said. Also, two other men from the neighborhood had died in the past few months. “Death,” she’d explained, “comes in threes.” Angelina had a litany of signs, dreams of clear water, of teeth falling out of her mouth; a dead bird on her doorstep; goose bumps in still, warm air.

But Mary had none of this. No dreams or dead birds or howling dogs. What she had was a typical day. A good day. At five, Stella still drank a bottle of milk in the morning and one at bedtime, a secret they kept from her kindergarten friends. Dylan brought her, happily and sleepily sucking her bottle, into bed with them and they cuddled there, Mary and Dylan reading the newspaper and Stella watching Sesame Street.

They knew it was time to get up when Stella came to life. No longer sleepy, she would start to tickle Dylan. Mary wished she could remember what they’d had for breakfast that last morning together, what they talked about over Eggos or cinnamon toast. But so ordinary was that morning that she cannot recall such details.

She knows that Stella wore striped tights and polka-dot clogs and a jumper that was too long, also striped. But she knows this because after Stella died, when they came home from the hospital, these clothes still lay in a crumpled heap, right where Stella had dropped them when she got ready for bed. She knows this because for days she carried them around, pressing them to her nose for the last hints of Stella’s little-girl scent.

Dylan had left that morning while they were still getting ready for school. He always left early, kissing them both on the top of their heads. Stella would yell, “Don’t go, Daddy!” and pout, making Mary a little jealous. It was true, she thought, that the parent who did the most caretaking, the driving around and cooking and bathing, didn’t get the adoration.

She felt guilty now, of course, that she had no doubt grown short with Stella for dawdling that morning. Stella was a dawdler, easily distracted by the sight of her forgotten rain boots or the sparkles on a picture she’d drawn and hung on the fridge. Even while Mary hurried her, Stella hummed and dawdled happily, grinning up at her mother as she rushed her into the car. “We’re going to be late,” Mary probably mumbled that morning, because they were usually late. And Stella probably said, “Uh-huh,” before she returned to her humming.

Mary stopped for coffee that morning, and visited with other mothers at the café, and shared funny stories about their amazing children; she went to work, wasting these last precious hours as a mother with reviews and research and other meaningless tasks; Dylan called her—he always did—to tell her when he’d be home that evening, to ask if Stella had anything special going on; then she raced to pick up her daughter at school, sat in the car, and watched her come out, dreamy and tired, her backpack dragging on the ground. And as she watched her, Mary’s heart soared; it always did when she saw Stella, her daughter, again.

Unlike the rest of that day, the clarity of their last evening together was so strong that it made Mary double over to remember it. All of it. The late afternoon sun in their kitchen. Stella working on her Weekly Reader. Lighting the grill for an early barbecue. Stella drizzling the olive oil on the chicken. Stella scrubbing the dusty outdoor table and chairs, placing the napkins so carefully beside each plate, running into Dylan’s arms when he walked into the backyard, grinning, pleased, and said: “A barbecue! In April!”“Yes,” Stella had said,“we’re eating outside!”

That night, Mary placed the portable CD player in the open window and played Stella’s favorite CD of dance music, the two of them dancing barefoot: the Macarena, the chicken dance, the limbo, and finally Dylan joined them and all three danced to “Shout,” jumping and waving their arms. The sliver of a moon hung above them in the big glorious sky, like a blessing, Mary remembered thinking.

The morning of Stella’s funeral, Mary’s mother called.

“You have so many people with you,” she’d said. “I know you’ll understand if I go back this morning. The later flight gets in after midnight, and you have so many people with you.”

Mary had frowned, not believing what her mother was telling her. “You’re not coming?” she asked. She still wasn’t able to say her daughter’s name in the same sentence as “funeral” or “died” or “dead.”

“You understand, don’t you?” her mother had said, and Mary thought she heard pleading in her voice. While her mother explained about the connection in Mexico City, how far apart the gates were, how confusing Customs was there, Mary quietly hung up.

Her mother had disappointed her for her entire life. She was not the mother who went to school plays or parents’ nights; she gave praise rarely but never gushed or bragged; she had missed Mary’s wedding because of a strike in San Miguel, where she lived, that forced her to miss her flight to the States. “I’ll send you a nice gift,” she’d said. And she had. The next week a set of Mexican pottery arrived, with half of the plates broken in the journey.

But still, in this most terrible time, Mary had expected her mother to be there in a way she had not been able to so far. When Mary studied the faces in the church, saw the neighbors and colleagues and teachers and relatives and friends, disappointment filled her chest so that she couldn’t breathe. She had to sit down and gulp air. Her mother really had not come.

The flower arrangement her mother sent was the biggest of them all. Purple calla lilies, so many that they threatened to swallow the entire room. If Mary had had the energy, she would have thrown it out, that ostentatious apology. Instead, she purposely left it behind.

In the hot sticky summer right after Stella died, Mary’s mother called her. She had called once a week, offering advice. Usually Mary didn’t speak to her at all.

“What you need,” her mother told her, “is to learn to knit.”

“Right,” Mary said.

Her mother’s colonial house in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, had a bright blue door that led to a courtyard where a fountain gurgled and big pink flowers bloomed. She had stopped drinking when Mary was a senior in high school. Now that Mary thought about it, that was when her mother started knitting. One day, balls of yarn appeared everywhere. Her mother sat and studied patterns at the kitchen table, drinking coffee and chewing peppermint candies.

“Here’s what I’m hearing,” her mother said. “You can’t work, you can’t think, you can’t read.”

While her mother talked, Mary cried. Not the painful sobbing that had consumed her when Stella first died, but the almost constant crying that had replaced it. Her world, which had been so benign, had turned into a minefield. The grocery store held only the summer berries that Stella loved. Elevators only played Stella’s favorite song. And everywhere she walked she saw someone she had not seen since the funeral. Their faces changed when they saw her. Mary wanted to run from them and from the berries and the songs and the whole world that had once held her and Stella so safely.

“There’s something about knitting,” her mother said. “You have to concentrate, but not really. Your hands keep moving and moving and somehow it calms your brain.”

“Great, Mom,” Mary said. “I’ll look into it.”

Then she’d climbed back into bed.

When Mary gave birth to Stella, she promised her that very first night that they would be different. Mary was going to be the mother she’d always wished for, and Stella would be free to be Stella, whatever that meant. She had kept her word too. She had spent afternoons making party hats for stuffed animals, letting her own deadlines go unmet. She had let Stella wear stripes with polka dots, orange earmuffs indoors, tutus to the grocery store.

They looked alike, Mary and Stella. The same shade of brown hair with the same red highlights that showed up in bright sunlight or by midsummer. The same mouths, a little too wide and too large for their narrow faces. But it was that mouth that gave them both such a killer smile. It was Mary’s father’s mouth that they’d both inherited, but in his later life it had turned downward, making him look like one of those sad-faced clowns in bad paintings.

Dylan used to joke that Mary hadn’t needed him at all to make Stella. “She’s you through and through,” he’d say. The only thing Stella had that was all her own were her blue eyes. Both Mary and Dylan had brown eyes, but Stella’s were bright blue. Not unlike Mary’s mother’s eyes, she knew, but hated to admit. Still, the overall effect was that Stella was a miniature version of Mary, right down to the long narrow feet. Mary wore a size ten shoe, and surely Stella would have too.

For fun, they would sometimes both dress in all black and Stella would make them stand in front of the mirror on the back of Mary’s closet door and grin together. “You look just like me,” Stella would say proudly. And Mary’s heart would seem to expand, as if it might burst through her ribs. She had done just as she promised. She was a good mother. Her daughter loved her.

As a child, Mary’s life was rigid, structured, and controlled by her mother. Breakfast had all the food groups. Shoes and pocketbooks matched. Hair was pulled into two neat braids, made so tightly that Mary suffered headaches after school until she could free them. Then she would sit and rub her head, wincing.

As she got older, Mary understood that all of her mother’s rules, all of the structure she imposed, were an effort to hide her drinking. When she came home from school, Mary sat at the kitchen table to do her homework, in a desperate need to be near her mother. Her mother would make dinner, sipping water as she cooked, The Joy of Cooking propped up on a Lucite cookbook stand. Mary found it ironic that this was her mother’s cookbook of choice since she seemed to take no joy in cooking or eating.

Still, Mary sat at that kitchen table every afternoon, sometimes asking her mother for help even if she didn’t need it, just so that her mother would come close to her. Mary would study her mother’s beautiful face then, the smooth skin and perfect turned-up nose, the shiny blond hair, and fall in love with this stranger each time. Her mother’s Chanel No. 5 would fill Mary, would make her dizzy.

Sometimes at night, her mother passed out on the sofa, and her father would lift her like Sleeping Beauty into his arms and carry her to bed. “Your mother works so hard,” he’d say when he returned. Mary would nod, even though, other than cleaning, she had no idea what her mother did. Then, that night when she was a sophomore in high school, while she was doing the dishes, Mary pressed her own chapped lips to the rosy lipsticked imprint of her mother’s on the water glass. She could taste the crayon taste of the lipstick, and then, sipping, the shock of vodka. All of those afternoons, her mother cooking with such concentration, those nights when she passed out on the sofa, her mother had been drunk. The realization did not shock Mary. Instead, it simply explained everything. Everything except why a woman so beautiful would drink so much.

That sad summer, time passed indifferently. Mary would lie in bed and think of what she should be doing—putting on Stella’s socks for her, cutting the crust off her sandwiches, gushing over a new art project, hustling her off to ballet class. Instead, she was home not knowing what to do with all of the endless hours in each day.

Mary was a writer for the local alternative newspaper, Eight Days a Week, affectionately referred to as Eight Days. She reviewed movies and restaurants and books. Every week since Stella had died, her boss Eddie called and offered her a small assignment. “Just one hundred words,” he’d say. “One hundred words about anything at all.” Holly, the office manager, came by with gooey cakes she had baked. Mary would glimpse her getting out of her vintage baby blue Bug, with her pale blond hair and big round blue eyes, unfolding her extralong legs and looking teary-eyed at the house, and she would pretend she wasn’t home. Holly would ring the doorbell a dozen times or more before giving up and leaving the sugary red velvet cake or the sweet white one with canned pineapple and maraschino cherries and too-sweet coconut on the front steps.

Mary used to go out several times a week, with her husband Dylan or her girlfriends, or even with Stella, to try a new Thai restaurant or see the latest French film. Her hours were crammed with things to do, to see, to think about. Books, for example. She was always reading two or three at a time. One would be open on the coffee table and another by her bed, and a third, poetry or short stories, was tucked in her bag to read while Stella ran with her friends around the neighborhood playground.

And Mary used to have ideas about all of these things. She used to believe firmly that Providence needed a good Mexican restaurant. She could pontificate on this for hours. She worried over the demise of the romantic comedy. She had started to prefer nonfiction to fiction. Why was this? she would wonder out loud frequently.

How had she been so passionate about all of these senseless things? Now her brain could no longer organize material. She didn’t understand what she had read or watched or heard. Food tasted like nothing, like air. When she ate, she thought of Stella’s Goodnight Moon book, and of how Stella would say the words before Mary could read them out loud: Goodnight mush. Goodnight nothing. It was as if she could almost hear her daughter’s voice, but not quite, and she would strain to find it in the silent house.

She imagined learning Italian. She imagined writing poetry about her grief. She imagined writing a novel, a novel in which a child is heroically saved. But words, the very things that had always rescued her, failed her.

“How’s the knitting?” her mother asked her several weeks after suggesting Mary learn.

It was July by then.

“Haven’t gotten around to it yet,” Mary had mumbled.

“Mary, you need a distraction,” her mother said. In the background Mary heard voices speaking in Spanish. Maybe she should learn Spanish instead of Italian.

“Don’t tell me what I need,” she said. “Okay?”

“Okay,” her mother said.

In August, Dylan surprised her with a trip to Italy.

He had gone back to work right away. The fact that he had a law firm and clients who depended on him made Mary envious. Her office at home, once a walk-in closet off the master bedroom, had slowly returned to its former closet self. Sympathy cards, CDs, copies of books and poems and inspirational plaques, all the things friends had sent them, got stacked up in her office. There was a whole box in there of porcelain angels, brown-haired angels that were supposed to represent Stella but looked fake and trivial to Mary. Stella’s kindergarten teacher had shown up with a shoe box of Stella’s work. Carefully written numbers and words, drawings and workbooks, all of it now in a box in her office.

“I figured,” Dylan had said, clutching the plane tickets in his hands like his life depended on them, “if we’re going to sit and cry all the time, we might as well sit and cry in Italy. Plus, you said something about learning Italian?”

His eyes were red-rimmed and he had lost weight, enough to show more lines in his face. He had one of those faces that wore lines well, and ever since she’d met him Mary had loved those creases. But now they made him look weary. His own eyes were changeable—brown with flecks of gold and green that could take on more color in certain weather or when he wore particular colors. But lately they had stayed flat brown, the bright green and gold almost gone completely.

She couldn’t disappoint him by telling him that even English was hard to manage, that memorizing verb conjugations and vocabulary words would be impossible. The only language she could speak was grief. How could he not know that?

Instead, she said, “I love you.” She did. She loved him. But even that didn’t feel like anything anymore.

They spent a very peaceful two weeks in a large rented farmhouse, with a cook who came each morning with fresh rolls, who made them fresh espresso and greeted them with a sumptuous dinner when they returned at dusk. The time passed peacefully, though mournfully. The change of scene and change of routine was healing, however, and Mary hoped that they might return with a somewhat changed attitude. But, of course, home only brought back the reality of their loss, their sadness returning powerfully.

That first night, as Mary stood unpacking olive oil and long strands of sun-dried tomatoes, the answering machine messages played into the kitchen.

“My name is Alice. I own Big Alice’s Sit and Knit—”

“The what?” Dylan said.

“Ssshhh,” Mary said.

“—if you come in early Tuesday morning I can teach you to knit myself. Any Tuesday really. Before eleven. See you then.”

“Knitting?” Dylan said. “You can’t even sew on a button.”

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.