Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

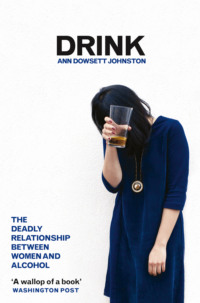

Kitabı oku: «Drink: The Deadly Relationship Between Women and Alcohol», sayfa 2

This is how it begins. You set some rules.

Maybe you switch from red to white (less staining on the teeth).

Or maybe it’s no wine; only beer.

No brown liquids, only clear. (Vodka doesn’t smell, does it?)

Only on weekends.

Never on Sundays.

Never, ever alone.

The problem is: The rules continue to change. Your drinking doesn’t.

You take up running or swimming. (In my case, it was power-walking. People who power-walk can’t be alcoholics, can they?)

You start to wake at four in the morning. (Doesn’t everyone wake at four in the morning?)

You promise to do better tonight, to drink less.

Only you don’t.

In fact, the only commitment you seem able to keep is the diary. It tells a story, and the story is starting to look scary.

Worse still? This is only the beginning of the end.

Like many a drinking diary, mine started off well. For a few days, the monkey stickers began to accumulate: I had kept to my limits. Of course, I kept the diary hidden. (What vice principal pastes monkey stickers into a journal?) But it wasn’t long before those stickers petered out. Alcohol is a formidable enemy: once you name it, it digs in hard.

I said this to the addiction doctor in March. He nodded. “How do you feel about alcohol now?” he asked. “I love it.” He frowned. “And I hate it.” “Be careful,” he warned. “Alcohol is a trickster. And using alcohol to cope is maladaptive behavior.”

One spring evening, I had dinner with the eloquent dean of medicine, Rich Levin. He was newish to McGill, having moved with his wife from New York, and he had had a difficult day.

Rich was a martini drinker, and he ordered one, then another.

“Why did you come to Montreal, Rich?”

“I came here for the waters.”

I fell for it. “The waters?”

“Turns out I was misinformed.”

I looked puzzled.

“Casablanca.”

“Another drink, Rich?”

“Never, my dear. You know what Dorothy Parker says.”

The next time I saw him, Rich pulled a gently used cocktail napkin from his pocket and handed it to me. There were Parker’s words, emblazoned beside a martini glass: “I love a martini—but two at the most. Three I’m under the table, four, I’m under the host.”

That night, I pasted the napkin into my diary. Beside it I wrote: “I am bullied by alcohol. I am hiding behind it.” I knew the jig was up.

Days later, on Father’s Day morning, I learn that my cousin Doug—childhood confidant and best friend—had been killed by a drunk driver, on his way home from his mother’s eightieth-birthday celebration. His young daughter, the youngest of four, was in the front seat. She survived but was severely injured.

It was a sunny Sunday morning, and I remember thinking: “What else do you have to lose to alcohol before you give up?” I had already lost a big part of my childhood, now my cousin—and I was losing myself.

I pulled out a bulletin board and tacked a piece of paper with four handwritten words at the top: “The Wall of Why.” As in, why I needed to give up drinking. Or: why I needed to avoid dying. The diary was no longer working. In fact, it had never worked. For the first time, I was terrified this habit might kill me.

I spent an hour filling the board with images and words I loved. In that condo, I had very few photographs—one of Nicholas with his arm around me, after winning bronze at a rowing regatta; one of Jake casting a line off the houseboat deck; one of my dog Bo. There were so many faces missing. I took out my fountain pen and wrote the names of others on pieces of white paper, pinning them carefully to the board. Then, I added several pieces of prose—Annie Dillard, Simone Weil—and some poetry: “Love after Love,” by Derek Walcott.

Then I got down on my knees and said the only prayer I believed in, words from T. S. Eliot’s “East Coker”:

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith.

But the faith, and the love, and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Within weeks, Jake and I would find our way to a recovery meeting in a church basement. He held my hand while tears rivered down my cheeks. For an hour I listened to a roomful of seemingly happy people share their stories, their faith, their gratitude. As they started to stack the chairs, a tall black stranger in a funky hat came up to comfort me. “Darlin’,” he drawled, “believe me, whatever you did wrong, I did way, way worse.”

Every season has its own soundtrack: that summer, it was Keith Jarrett’s introspective Köln Concert wafting over pink-streaked granite, keeping us company as we drank cranberry juice and soda with our meals. Jake’s precious mother had just died a difficult death. When Jarrett felt too haunting, Jake would toss in a little Frank or Van to keep the tone romantic. “I’m making love to you with my playlist,” he’d call out from his computer, and I’d be enveloped, newly sober, in a fresh cocoon of sound.

But for the rest of the world, the summer of 2007 belonged to the defiant Amy Winehouse: “They tried to make me go to rehab. I said No, no, no!” An earworm if ever there was one. The point wasn’t lost on me as I headed back to McGill, having tallied my first seventeen days of sobriety in the north woods of Ontario. Checking my BlackBerry as I cabbed in from the airport, I found myself humming along. “No, no, no!”

Little did I understand that it would be more than a year before I was able to secure any meaningful sobriety, to put alcohol somewhat solidly in my rearview mirror. It would be three years after that before I regained what could be called a true sense of equilibrium. And it would take all my journalistic skills to put what was killing me—and as it turns out, a growing number of women—into some profound and meaningful context.

In the meantime, I was about to lose many things I cared about: my livelihood, my heart, my gusto. And before things got better, they were going to get as tough as tough could be.

2.

Out of Africa

A FAMILY UNRAVELS

One always learns one’s mystery at the price of one’s innocence.

—ROBERTSON DAVIES

I had a bifurcated childhood, split perfectly down the middle between joy and distress. Most of the latter was alcohol-fueled. My sister and brother will attest to this, and my mother will as well: there was great happiness, despite the extended absences of my peripatetic father, followed by years of terrible despair, years we barely survived.

What we don’t agree on is when it all changed. For me, it split pretty tidily this way: before South Africa—a move we made when I was nine—and after South Africa. South Africa was the hinge experience. Once we had been there, it seemed there was no turning back.

Before we moved, there were many memories, but none so dominant as my mother’s devotion to her parents. Night after night, I fell asleep to the sound of her typewriter keys as she wrote her long letters home. Handel or Beethoven on the record player, clackety-clack. Telling them of her life in a small northern mining town, with three small children, where the whistle blew every evening to signal that the miners’ day had ended. Clackety-clack. Writing of life alone with those small children. My father in Africa or Australia, a geophysicist overseeing exploration in the outback. Clackety-clack. Once in a while she would go to her bridge club. Kissing me when she returned, she smelled of cold air and clean hair and Guerlain’s l’Heure Bleue. But those evenings were rare. Most evenings, I fell asleep to the comforting sound of her keys.

And then glorious silence: come June, the typing would stop and we’d hit the road.

Year after sunburned year—long before people worried about global warming or SPF—we would escape for the entire season. As soon as school was out, my mother would load up the car and head off down the highway. In the trunk would be our tartan cooler, the car rug for picnics, plus an entire suitcase of library books. In the backseat: the dog, my sister, my brother, and I, unencumbered by care—or seat belts, for that matter.

On paper, my mother would say we were Protestants. But in reality, heading to the cottage was our religion: we were the true believers. Not that we worshipped in just one spot. As newlyweds, my parents had honeymooned at my father’s family place, a log cabin on a sheltered teacup of a lake near Algonquin Park, the same lake where iconic Canadian painter Tom Thomson planned to honeymoon before he mysteriously drowned. But after that initial trip, they split their vacation time between their families’ summer homes. And since my father’s holiday time was limited, more often than not we would find ourselves nestled in the bunk beds of my mother’s childhood cottage on a stretch of Georgian Bay, a place where August storms swaggered in at night, tossing sailboats at their moorings, working their bonsai magic on the pines.

Thanks to my two grandfathers—both of whom had fought in the First World War, one as a fighter pilot, the other having his leg shattered at Passchendaele—there were two log cabins we called home. During the 1930s, they and their spunky wives had searched the north country for land, tenting with their children before the cottages were built. In my maternal grandparents’ case, they bought a local farmer’s log home for five hundred dollars in 1930 and had the thick hemlock timbers numbered and transported by horse and wagon to be reassembled by the shores of Georgian Bay. My paternal grandparents, on the other hand, built a tidy one-room log place from scratch, adding little pine bunkhouses along the shoreline as their family grew.

As a result, we gorged on summer in two distinctly different places. At the little lake cabin, we would fall asleep to the mournful call of loons, snug under heavy red Hudson Bay blankets, in flannel pajamas my mother had warmed by the fire, our hair smelling of wood smoke. My sister Cate and I would whisper by the dying light of the woodstove. What was that noise? Was it a bear? Or a ghost? I was sure there were ghosts. Poor Tom Thomson, vengeful in his soggy plaid shirt, rising from his watery grave to return to his never-to-be honeymoon spot, wielding an axe. Always an axe, to give us forty whacks.

Before I knew it, morning would break with a slam, my grandmother’s screen door announcing she was up, coffee on, porridge started. Time for the morning paddle to the lodge to see if the paper had arrived. Within minutes we would be off, her voice ringing clear across the mirrored water: “By the li-i-ight of the sil-ver-eee moo-oo-oon …” Another day had begun, a day of snooping in the woods, racing to the raft, horsing around with the Patterson boys.

At the other cottage, days and nights were different. There I would fall asleep to the sulky rhythm of Georgian Bay and the tinkling sounds of masts, the sweet taste of marshmallow in my mouth and even sweeter comfort of my cousins. By day I’d wake to thick wedges of sunlight on the painted floorboards and the whirrrr-dee-dee-dee of the birds. In a flash, I’d be downstairs, joining Dougie as he cracked open a new variety pack of little boxed cereals, dousing his bowl of Frosted Flakes in chocolate milk because shhh, the mothers were still sleeping. Off we would tramp in our still-damp bathing suits to our secret fort at the Point. Back to the cottage to head out in the Swallow, our bathtub of a homemade rowboat. Adventure after adventure, punctuated only by meals, served by my mother and aunts and grandmother on little birch-bark place mats, ones sold by the “Indians,” said my mother, “when they used to tent on the Point.”

All week long the cottage was a women-and-children affair. But on Friday afternoons the air would begin to crackle. For hours we would line ourselves along the top of the split-rail fence, chirpy faces trained toward the curve, looking for the first sign of a Buick. My mother would head into the bedroom to brush her freshly washed hair, put on lipstick, and emerge transformed: burnished and blond for my dad. I thought she looked like a movie star.

For the next two days there would be laughter: games of charades, rounds of bridge, impromptu skits. Tall shoulders to be tossed from, into the water; strong arms to help us build boats and forts. Handsome men drinking “Hey Mabel, Black Label” beer after splitting logs and stacking the woodpile. Was there too much drinking? I have no idea. All I remember is that most of the adults smoked cigarettes or pipes—and we did, too, sneaking them into our homemade tepee. It was a poor plan. The smoke billowed out the top and we were caught, red-handed, forced to chain-smoke until we turned green.

At night, lying under white sheets, little needles of sunburn prickling our shoulders, our noses peeling for the umpteenth time, my cousin and I would decide that no, we weren’t going to sleep, not when the adults were telling dirty jokes downstairs. And so we would eavesdrop, and then whisper very quietly, because “for the last time, kids,” my uncle had warned, “it’s time to go to sleep!”

Then it would be Sunday night, and we would all wave as the cars, honking, disappeared around the curve, and the cycle would begin again.

Often there was a visitor I loved: the painter A. Y. Jackson, a close friend of my grandparents. A bachelor with an infamous appetite for my grandmother’s jam—jam that would dribble down his sweater vests along with his cigarette ashes when he chuckled at my grandfather’s jokes. Looking at his belly, I knew why Aunt Esther had never married him. “I’ll be away many weeks of the year,” he had warned when he proposed. “Make it fifty-two, and I might agree,” was her response.

Or that’s how the story went. Maybe he never really wanted to get married. Maybe he was afraid of marriage the same way he was afraid of fire. In one of the cottage bedrooms, he had had my grandfather install a thick rope, attached at the windowsill so he could shimmy down it in the event of a blaze. (He never used it, but Dougie did, when we played hide-and-seek.)

Clearly, this was a man who liked to escape, just like my father. He stole my heart because he taught me how to steer a paintbrush with my thumb, and because he painted a naughty little sketch of a Shell station with the S missing. He was just about the only bachelor I had ever met, a rambling guy whose snowshoes hung on the wall beside the fireplace. But I used to think that maybe he’d outfoxed himself, taking all those painting trips and somehow forgetting to get married and have his own little family to go home to.

Year after sunburned year, this was how we lived. If my father was away more than most—and he always was—summers buffered my mother from her pervasive loneliness. She flourished near family, and so did we.

When this chapter ended—when her parents died too young, and her drinking started—I used to think that those summers at the cottage were like money in the bank or gas in the tank: she had accumulated so many good memories for us that it took a long time to get to zero.

Of course, we did get to zero, and far, far beyond in those many years when her drinking was dire, when she seemed to give up eating and sleeping, weaving down the halls like a passenger on a bumpy train, the sound of ice cubes declaring her arrival. But that was much later, after the cottages had been split up and the cousins had scattered, a long time after Africa.

Rural South Africa, 1963

The birth of anxiety.

An outdoor music festival. I am ten years old, about to sing my first solo, “All Through the Night.”

Suddenly, the large Afrikaans woman next to me starts to slap my arm. I can’t understand a word she’s saying. (Turns out, I’m not clapping for her son, my competition, who’s taking a bow.)

Now it’s my turn to take the stage. I freeze.

The audience starts to mumble.

The judge walks over to see what’s wrong. My father comes, too. He talks me into performing. Maybe after the lunch break, suggests the judge. I nod. I can do this, on one condition. I don’t think I can face the crowd. The judge smiles. No, it’s not essential to face forward.

After lunch, I keep my promise. On uncertain legs, I climb the stage. I turn to face my teacher, Mrs. Duplessis, at the piano. My back is to the audience.

At the end of the afternoon, I’m awarded second prize: first for voice, marks off for delivery.

Many years later, as I wrestled with major depression and a serious case of writer’s block, the judge’s verdict would become a constant in my head: “First for voice, marks off for delivery.” Code for: you’re failing.

For decades I forgot this incident. Then it reappeared, just as I was to deliver a cover story on teenage suicide. Frozen at my computer, I would hear the judge’s words, over and over, in my head.

In Montreal, as my world unraveled on the fifteenth floor of the student residence, I heard it again: “First for voice, marks off for delivery.”

What does this story have to do with my drinking?

Everything.

Liquor soothes. It calms anxiety. It numbs depression. Ask any serious drinker: if you want to find your off button, alcohol can seem like an excellent choice.

But not when you’re ten.

Back then, as I sat with my parents on sticky chairs on an unforgiving African afternoon, my confidence was deeply shaken. I was pink with humiliation. And I felt my parents’ confusion at my behavior. I had always been top of my class. I had accelerated at school. I had never blown anything this badly before.

It was a wobbly time for me.

For my parents, our move to Africa was their great romantic adventure. For the first time in their marriage, they had finessed their situation and were truly together in a sustaining fashion: making a home on an acre in Mount Ayliff, a village of a hundred people nestled in the hilly terrain of the Transkei. All of a sudden there was a cook, a maid, a garden boy. Each night, my father would park his Land Rover out front and saunter through the door, darkly handsome in his khaki field clothes. He would light the propane lanterns—there was no electricity—and cast a warm glow through the long-halled house. My mother was delighted.

For me, he was our bachelor father, and everything seemed new. At dinner, when my mother’s back was turned, he’d line his peas on his knife and toss them down his gullet, pressing his finger to his lips: “Shhhh!” “What, John? What did you just do?” We’d giggle. When she wasn’t looking, he’d open the fridge and swig milk straight from the bottle. This guy didn’t seem to know the rules.

At bedtime, he’d read to us: Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. My mother was in love with him, and we were, too: this dad was different than the person I expected, but he made the house hum. My mother was chatty, extroverted, radiant. They entertained, and there was laughter. This was an era of cinch-waisted dresses and “sundowners.”

I knew I was meant to be happy. But for me there was a deep sense of foreboding, a shadow I could not shake. And it went deeper than the obvious disappointment that I was no longer my mother’s primary companion, the eldest with special privileges.

More often than not, I felt like the bad fairy at the birthday party. There was a deep, subterranean rumble I could feel, although I couldn’t put my finger on it. Something was not right.

It started with our trips to the library, back in Canada, when we were busy getting shots and passports. While the librarian was loading my sister’s arms with animal books—books full of lions and poisonous snakes—I was reading stories about violence in the Belgian Congo, murder. I was deeply skeptical about this trip, and my fears seemed justified. When our plane landed for refueling in the Congo, en route to Johannesburg, I thought that the cleaners were boarding to kill us: I ran to the washroom, burst in on a man shaving, and promptly threw up. When my father introduced us to the snakebite kit in the kitchen, my fears were confirmed: this was African Gothic.

I had always loved school. But in Mount Ayliff’s barren two-room schoolhouse—twenty students in eight grades—I couldn’t understand a word being said. This was Afrikaans immersion, and I was lost. For the first time in my life, I was bullied on a regular basis. While two large boys would pin me to the ground, another would hold an insect close to my face, tearing its legs off, yelling at me for speaking English. I didn’t tell my parents: as far as I was concerned, there wasn’t much point. They didn’t know Afrikaans, either.

Of course, in a very short time, my sister and I learned Afrikaans and Xhosa, too, the Bantu language spoken by our servants. I found a defender at school, a much younger English boy named Nicky Hastie, so staunchly loyal that I later named my son after him. My sister and I adopted a pet frog, named him Sam, and carried him to school in a little cardboard suitcase. He lived under my desk, and I’d peek on him when Mrs. Duplessis had her back turned.

In other words, we adjusted. While my mother developed a close relationship with our cook, we learned that the maid had a vicious temper and hated children. When my mother was out, she would threaten us with a hot iron, chasing us down the long halls of the house. On more than one occasion, she burned a hole in my sister’s favorite blue dress.

One Saturday night, we paid her back. Left in her care, we disappeared into our bedroom wardrobe, leading her to believe we had run away. Screaming at the sight of our empty beds, she ran to the servants’ quarters to fetch the cook. By the time she showed up, we were safe and sound. The cook left, and we hopped back in the wardrobe. Later, the maid would get even: when we headed back to Canada, we knew she was planning to chop the heads off our favorite bantam chickens to cook them for dinner. But by then our little pack of three was well established: John and Cate and I were tight as tight could be, and that fact would never change.

On Thursdays, Cate and I would wander by the local jail on our way home from piano lessons, passing hard candies through the fence to the neighbor’s former cook. Rumor had it that she had killed a younger servant, whom she had caught sleeping with her boyfriend, the garden boy. Maybe it was the garden boy she killed. We weren’t concerned: we loved her for the corn bread she had cooked, and for the hugs she gave us when we first arrived in the village. We liked her smile (although I used to imagine her washing the blood off the knife, after she stabbed the person; I thought she must be very brave).

There was a political undercurrent in the village. We knew we were the last whites to live in Mount Ayliff, that soon this would be the first homeland given back to the blacks. One Saturday a group decided to speed up the process: they would burn the whites out of town. They warned two families to leave: ours and the doctor’s. My parents woke us in the middle of the night and told us to get our clothes on: we had to decide whether to evacuate or not. We ended up staying. The crisis was averted, but the anger was real.

At Christmas, my mother gave both Ivy and Evelina presents. And on Christmas night our family joined a handful of others, sitting in church with the black congregation. Soon after there was a visit from the police: presents, they said, were not a good idea. Nor were the mattresses in the servants’ quarters. My feisty mother was unfazed.

On vacations we would visit the Indian Ocean or a game park. Truth be told, I always thought those trips were risky business: I had been chased by a herd of warthogs and was certain it was only a matter of time before we were killed or maimed. While others enjoyed the view, watching monkeys try to pry open the car, I usually had my eyes trained out the back window, checking for a marauding rhino.

On weekends we would head off in our big boat of a Mercedes and end up at the Stanfords’ ranch, where my parents would ride horses into the mountains, coming back with stories of baboons and more. My mother always looked so gorgeous on a horse, her hair windswept, a girlish joy on her face. She loved the adventure, and I thought she was remarkable, going off as she did, facing baboons. Remarkable, and a little reckless.

While they were gone, we would play hide-and-seek with the Stanford girls, discuss what little we knew of the facts of life, and look after our baby brothers. I liked those weekends: it felt like the cottage, with my cousins. I finally felt at home.

And then it was over. Before we headed back to Canada, my father presented my mother with a beautiful double-diamond ring to celebrate their African honeymoon. For two solid months we meandered up through Africa, from Zanzibar to Kenya, on to Egypt and Greece, Italy, Switzerland, and more, traipsing hand in hand like the happy band that we were.

Years and years later, after we were all married, my parents moved back to Africa, spending six years in Botswana. They took a trip one Christmas, down through South Africa, to visit old friends, stopping in at Mount Ayliff on their way. Our house was now a magistrate’s office; the neighbor’s house was lined with broken beer bottles. The garden was long gone. My mother said she was sorry she ever saw our home that way: it broke her heart.

By then it was the 1980s, and everything had changed. My mother’s years of heavy drinking had cast a terrible pall over our entire family. While loneliness, depression, and anxiety would take me down, something took her far, far further. For years, she—like so many other women—added Valium to the mix, and it diminished her. The woman we knew in Africa had disappeared, and in her place was someone full of rage, bitterness, and despair. Most of all, she was completely unpredictable. One minute our mother was present; the next she had transformed into Medusa with a tinkling glass.

I often look at photos of all of us on the trip home from Africa—pictures in Florence and Athens and Cairo—and wonder if anything had started to go wrong. Dad slim and tanned in his Ray-Bans, Mum just steps ahead in linen and pearls, and those Jackie Kennedy shades. Both look inordinately happy. Did Dad know what was about to happen? Did she? Had the drinking turned dangerous already?

I think not. If anything, the time in South Africa was too good: my mother never quite readjusted to her loneliness again, and she never forgave my father for leaving her behind. It was decades before they would have another big shared adventure. And in the intervening years, life was very tough.

Or that’s how I see it. It’s one way I have been able to make sense of the story, to love her through the madness. It’s tough to parse addiction, even when you’ve succumbed to it yourself.

Most of all, I like to remember my parents the way they were in Rome. My father, scooping my mother in his arms, carrying her up the hotel stairs. Her head tossed back, laughing: “Oh, John!”

I never saw her laugh quite that way again. Once her parents died, both from cancer when they were barely into their seventies, and my father resumed his overseas travel, she took her comfort in hard liquor. For years she seemed to live in her nightgown, wandering the halls by night, cursing by day. “This isn’t living, it’s existing,” she would announce, over and over, her eyes belligerent. “I’ve had it up to here”—gesturing to her neck—“and the rest is toilet paper!”

At sixteen, I began my feeble attempts to leave home. If my father was around to hold the fort, I would pack a small bag and head off on foot, aiming for my cousins’ house. I would never make it very far before my father would retrieve me, slowing down beside me in the family car. “Get in, Ann. Your mother needs you.” And back I would go, in tears, to a house that felt like it was on fire, burning with rage.

Perhaps because he knew just how difficult my mother found his absences, and because he loved her, my father stood by her. We often wondered why, and how, he was able to do this.

Only once did he lose his temper in front of us, and the image is seared deeply in all our brains. He has lined us up in the kitchen—my mother, my sister, my brother, and me—making sure we are watching as he smashes all the bottles he has found in the house, breaking them, one by one, over the kitchen faucet. Bottle after bottle in his powerful hands, crashing on that slim bit of curved aluminum, until he punctures it and it begins to spout like a whale. Broken glass, spouting water. And we all stand, dumbfounded, tears of fury and despair rolling down my poor father’s face, tears of contrition pouring down my poor mother’s cheeks, all of us trapped in the hell of a family cursed by addiction, with no escape pending.

For years she was on the phone, drinking and dialing. Sober, she rarely picked up. Drinking? No call was too difficult, including to the police. More than once I had a date interrupted by a cop. “Your mother needs to find you,” they’d say. “There’s a family emergency.” And I’d roll my eyes. If there was one quality I hated most, it was her disinhibition.

The bills added up. Once, my father had the phone cut off, and there we were, having to explain to our friends that ours was a phoneless household. There was no end to the embarrassment.

Years later, when we had all left home and wanted to visit them, my father would rarely warn us if she was on a bender. We’d just arrive, and be back in living hell. Later he learned to give us a tip-off. “Your mother is not feeling very well today,” he would say. It was a feeble bit of code: I used to be angry that he didn’t name it for what it was. But it seemed he could not.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.