Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

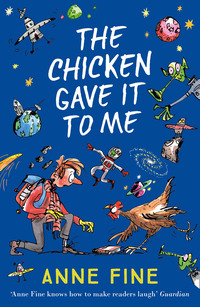

Kitabı oku: «The Chicken Gave it to Me»

Also by Anne Fine

For Clare Druce

Contents

1 A tiny little book

2 The True Story of Harrowing Farm

3 Harpoon . . . Harpsichord . . . Harridan

4 I go chicken-dippy

5 Penguins or cheetahs, whales or sharks

6 I show myself to be naturally chicken-hearted

7 ‘Not today, thank you.’

8 Chicken no longer

9 Just a toy

10 Green sky. Green earth. Green wind. Green sand.

11 ‘No fear!’

12 Chicken of history

13 Been done before

14 Chat show chicken

15 In front of frillions

16 Chicken celebrity

17 Out it came

18 Surprises, surprises!

19 The last few words

20 Close them all

1

A tiny little book

Andrew laid it on Gemma’s desk. A cloud of farmyard dust puffed up in her face. The first thing she asked when she stopped sneezing was:

‘Where did you get that?’

‘The chicken gave it to me.’

‘What chicken? How could a chicken give it to you? It’s a book.’

It was, too. A tiny little book. The cover was just a bit of old farm sack with edges that looked as if they had been – yes – pecked. And the writing was all thin and scratchy and – there’s no way round this – chickeny.

‘This is ridiculous! Chickens can’t write books. Chickens can’t read.’

‘The chicken gave it to me,’ Andrew repeated helplessly.

‘But how?’

So Andrew told her how he’d been walking past the fence that ran round the farm sheds, and suddenly this chicken had leaped out in front of him in the narrow pathway.

‘Pounced on me, really.’

‘Don’t be silly, Andrew. Chickens don’t pounce.’

‘This one did,’ Andrew said stubbornly. ‘It fluttered and squawked and made the most tremendous fuss. I was quite frightened. And it kept pushing this book at me with its scabby little foot – just pushing the book towards me whichever way I stepped. The chicken was absolutely determined I should take it.’

Gemma sat back in her desk and stared. She stared at Andrew as if she’d never even seen him before, as if they hadn’t been sharing a desk for weeks and weeks, borrowing each other’s rubbers, getting on one another’s nerves, telling each other secrets. She thought she knew him well. Had he gone mad?

‘Have you gone mad?’

Andrew leaned closer and hissed rather fiercely in her ear.

‘Listen,’ he said. ‘I didn’t choose to do this, you know. I didn’t want this to happen. I didn’t get out of bed this morning and fling back the curtains and say to myself, “Heigh-ho! What a great day to walk to school down the path by the farm sheds, minding my own business, and get attacked by some ferocious hen who has decided I am the one to read his wonderful book –”’

‘Her wonderful book,’ interrupted Gemma. ‘Hens aren’t him. They’re all her. That’s how they get to lay eggs.’

Andrew chose to ignore this.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘That’s what happened. Believe me or don’t believe me. I don’t care. I’m simply telling you that this chicken stood there making a giant fuss and kicking up a storm until I reached down to pick up her dusty little book. Then she calmed down and strolled off.’

‘Not strolled, Andrew,’ Gemma said. ‘Chickens don’t stroll. She may have strutted off. Or even –’

But Andrew had shoved his round little face right up close to Gemma’s, and he was hissing again.

‘Gemma! This is important. Don’t you see?’

And, all at once, Gemma believed him. Maybe she’d gone mad too. She didn’t know. But she didn’t think Andrew was making it up, and she didn’t think Andrew was dreaming.

The chicken gave it to him.

She picked it up. More dust puffed out as, carefully, she stretched the sacking cover flat on her desk to read the scratchy chicken writing of the title.

Opening it to the first page, she slid the book until it was exactly halfway between the two of them.

Together they began to read.

2

The True Story of Harrowing Farm

It was a wet and windy night, so wet you could slip and drown, so windy no one would hear your cries. Only a snake or a toad would choose to be away from shelter on such a night. And that is why only the snakes and the toads saw the gleaming green light pouring down from the black sky.

We chickens saw nothing, of course. How could we? There are no windows in the chicken shed. If we had windows, our lives could not be ruled so well by the electric light that decides when we wake and when we sleep and when we lay our eggs. After – oh, yes, of course, after – some of the hens in the cages by the door said that they’d heard the soft hum of the engines over the howling of the wind. But the rest of us think they were boasting. On that black night, the spaceship landed without a sound. And it was not until the shed door flew open, flooding us with an eerie green light, that most of us chickens woke with a flutter and a squawk.

Little green men.

And they spoke perfect Chicken. (Later we found out they spoke Pig and Cow and Crow and pretty well everything. It’s one of the ways in which they are, as they put it, ‘superior’. They can speak any language they happen to meet. But on that first night we were amazed that they spoke perfect Chicken.)

Not that they were polite with it.

‘Chickens!’ said the spindliest and greenest, and it was almost like a groan. ‘Travel a frillion miles, and what do you find when you arrive? A chicken!’

The others flicked the catches of our cage doors with their willowy green fingers.

‘Out, out!’ they called. ‘Wakey, wakey! Make room! Out you get! Clear off! Go and make your own nests! The party’s over!’

The party’s over? We chickens couldn’t believe our luck. We’d been locked in those cages almost since we were born. Nothing to do. You can’t even stretch your wings. You just stand there on a wire rack (ruining your feet) for your whole life. And the one thing they want you to do – laying your egg – you’d far rather do in private.

The party’s over! I can’t describe to you the din as we all fluttered clumsily down, and scrambled unsteadily for the door.

The little green men were even ruder now.

‘Call themselves chickens? I’ve seen finer specimens on other planets begging to be put down!’

‘Look at them! Twisted feet. Bare patches all over. And look at their beaks!’

‘Disgusting!’

‘Leave the door open as you go, please. This shed needs some fresh air.’

Fresh air! And we were out in it for the first time in our lives. We weren’t going to hang around shutting the shed door. No fear. We were away. The last I heard as I went hobbling off on my poor feet into the night was one of the little green men scolding the stragglers.

‘Hurry up. Out of those cages, please! We need tham for others.’

With one last shudder and a flutter, I was off.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.