Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

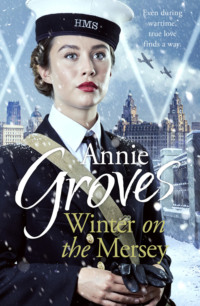

Kitabı oku: «Winter on the Mersey: A Heartwarming Christmas Saga», sayfa 2

Kitty had sat up straighter. Adding that to Marjorie’s crammer courses in French and German, this was a strong hint that her friend was going to be sent abroad – and that must mean it was very hush-hush. There were rumours of young women being sent on secret missions into enemy territory. Now maybe her friend was to be one of them.

‘Really?’ Kitty was impressed and filled with trepidation on Marjorie’s behalf. ‘And you are happy about it?’

Marjorie’s chin went up and her eyes were alight. ‘Yes, absolutely,’ she’d said. ‘I can’t tell you what I’m doing, Kitty – but I can tell you I’m pretty darn good at it.’

Kitty nodded. Coming from someone else it could have sounded like boasting, but Marjorie had never been like that. For all her social awkwardness to begin with, she’d never had any doubts about her academic abilities. She’d had to fight her family for the chance to use those talents as a teacher and now she was turning them to good use in the service of her country.

Kitty had grinned. ‘Well, good luck then.’ She’d raised her tea cup. ‘And let’s hope wherever it is there’ll be some dishy airmen to fill your leisure hours.’

Marjorie beamed. ‘Suppose there might be. It’s hard to say – they never brief you on all the really important things like that. If I’m really lucky there’ll be some fair-haired ones. That’ll take my mind off work very nicely indeed.’

‘Marjorie!’ Kitty pretended to be shocked, but she knew there was nothing Marjorie liked better than being whirled around the dance floor by a fair-haired pilot, particularly if he’d promised her a martini. It didn’t hurt to dream. Though there might not be many cocktails for her friend in the near future.

They’d parted shortly after, with hugs and promises to keep in touch if possible, and neither had given in to the thought that Marjorie was going into danger and they might never see one another again. Kitty picked sadly at the bedspread now, wondering what was in store for her friend. She didn’t doubt she had reserves of courage and resourcefulness, but she had seemed so small as she’d waved her goodbye on the train platform. ‘I haven’t been able to see Laura,’ Marjorie had said. ‘I’ll write of course, but if you see her, will you tell her I was thinking of her?’

‘Of course,’ Kitty had promised. Laura was the third of the group who’d bonded so closely during the initial weeks of training. She was still in London, working as a driver, horrifying her very well-to-do family with her willingness to get her hands dirty fixing engines rather than sitting in their ancient pile in Yorkshire making polite conversation.

Clearly Marjorie was so close to being sent off to do whatever it was that she couldn’t even make it up to London; if that was the case, perhaps Kitty could go in her stead. She brightened at the thought. She’d see when she next had leave and if it coincided with Laura being able to take some time off. That would be something to look forward to.

Danny Callaghan drew the rickety wooden chair closer to the fireplace. He had lit the kindling when he’d got in from work, and now he poked it and added a few pieces of coal, just enough to take the chill off the room which had been empty all day. He warmed his hands and then reached into his pocket for the letter he’d picked up off the worn doormat. The writing was familiar, scrappy and uneven, clearly done in a hurry.

Ripping open the envelope he was curious to see what his young brother Tommy had to say for himself. Tommy wrote often but never at great length. He had been evacuated to the same farm as their neighbour Rita’s children, where he’d soon taken to the life. Seth the farmer had been delighted as, having no son of his own, he had begun to struggle with all the daily tasks once his young farmhands had been called up. Tommy had become a real help. The arrangement suited everyone. In the past Tommy had been a proper handful, and had nearly got himself killed in a burning warehouse down at the docks, where he had had no business being in the first place. His older siblings had been at their wits’ end trying to work out how to keep him safe at home, and so sending him to the farm had been the best solution all round.

Danny drew out the single sheet of paper and scanned it quickly, then looked again more carefully. He’d been expecting more of the same sort of news that Tommy had been sending for the past couple of years: what fences he’d helped to mend, if the fox had managed to get into the hen house, what treats Joan, Seth’s wife, had baked. There was some of that, but the main reason Tommy had written was he wanted to come back to Bootle.

Danny groaned. Of course his little brother was growing up. He was thirteen now and would soon turn fourteen. It hadn’t escaped Tommy’s notice that this meant he could leave school. So he thought the best thing would be for him to move back in with Danny and then see if he could help the war effort in any way – he had heard that boys of fourteen could join the Merchant Navy.

‘Oh no,’ Danny breathed, knowing full well the sort of life that would mean. Plenty of the men and boys he knew who’d grown up around the docks had joined the Merchant Navy, and of course Eddy Feeny would come home with tales of what it was like, so Tommy knew all about it – or at least the tales of adventure, dodging U-boats, mixing with seamen of all nations, all working for a common cause. It would appeal to any boy. But Danny didn’t want his little brother to be in danger like that. He groaned aloud once more.

‘Danny! Whatever’s the matter?’ Sarah Feeny pushed open the back door and set down a scratched enamel pot on the hob in the back kitchen. ‘Mam made extra stew and thought you might like some. Don’t get your hopes up; it’s nearly all potato and beans, hardly any meat in it. Seriously, what’s wrong? You haven’t taken bad again, have you?’ Her animated face was etched with sudden concern.

‘No, no, nothing like that.’ Danny shook his head and his thick black hair glinted in the firelight. ‘You shouldn’t have.’ He nodded at the pot. ‘Thank your mam for me, she spoils me.’

‘She likes to,’ Sarah said with a grin, pulling up another chair. ‘So, tell me what’s happened.’ She shivered and drew her nurse’s cloak more tightly around her.

Danny let out a long sigh. ‘It’s our Tommy. This arrived today. He’s reminding me that he’s going to be fourteen soon and won’t have to go to school any more. He says he wants to join the Merchant Navy.’

Sarah gasped. Like Danny, she thought of Tommy as the young tearaway who’d settled down once he was given responsibility on the farm, and although if she’d added it up rationally she would have known how old he was, it was still a shock to realise he was well on the way to becoming a young man. ‘It doesn’t seem possible, Danny. Surely you don’t want that.’ She tried not to let her anxiety show, not only for Tommy but for Danny too. She knew better than anyone what he struggled so hard to keep hidden. Although technically now part of the Royal Navy, Danny had never gone – and could never go – to sea. All of the armed forces had turned him down, despite his obvious courage and willingness to sign up, as rheumatic fever had left him with an enlarged heart. Any extreme physical activity would put him at risk. They’d only found out when he’d stood in for a fallen fireman at a vast blaze down at the docks. Danny had taken the man’s place without hesitation but had collapsed afterwards. Sarah had rescued him but the news had got out. When it came to fighting for his country, Danny Callaghan was damaged goods.

By a stroke of luck, Danny had shown an uncommon aptitude for solving puzzles and crosswords while recuperating, and this had led to him being recruited to join Western Approaches Command, as they were in desperate need of that rare kind of skill to help decipher enemy signals. Frank Feeny worked there as a naval officer, and had recommended his old friend, against some opposition from the more traditional superior officers. Danny had only ever worked down on the docks up till then and had been a tearaway himself when in his teens.

This was exactly what was on Danny’s mind as he reread his little brother’s letter. He recognised that feeling of wanting to join up, do his bit, and also see the world and test himself against the odds, take a risk and worry about the consequences later. It was precisely why he wanted to protect Tommy from it. Now he was older, he wished he’d paid more attention at school, but at the time he couldn’t be bothered, couldn’t wait for it to end so he could get out and live his own life. It had meant that his work at Derby House had been extra hard to begin with as he’d had to learn so much from scratch. He could see with hindsight how he would have benefited from listening to his teachers when they’d insisted he could have gone further. All right, the family had needed him to go out and earn his keep – but he’d wasted the last year in the classroom. He wanted better for Tommy.

Now he looked across at Sarah, with her sleek brown hair pulled back away from her caring face, knowing that she’d be worried for him. He didn’t want his anxieties to burden her. ‘No, I’d much rather he stayed where he is. At least we know he’s safe there, and well fed.’

‘And Michael and Megan look up to him,’ Sarah said. ‘They’d miss him if he came back.’

‘It’s been good for him to be like a big brother to them,’ Danny agreed. ‘The trouble was, we all let him get away with murder because he was the youngest and he could wind us round his little finger. Now he’s had to grow up a bit.’

‘Sounds like he’s started to grow up a lot,’ Sarah said ruefully, getting to her feet and opening a cupboard. ‘Here, Danny, I’ll put this on a plate so you can have it now while it’s still warm. News always feels better after a full meal.’

She knew her way around the Callaghan kitchen as well as her own, as – ever since Kitty had left – Dolly would often make a bit extra for Danny and have Sarah take it across the street. ‘There you are.’ The delicious smell filled the small room, and Danny tucked in gratefully.

‘Thanks, Sar.’ Finally he pushed the plate away. ‘You’re right. You can’t make good decisions on an empty stomach.’

‘I wonder what Kitty thinks?’ Sarah replied. ‘Do you think he’ll have written to her as well? It’s not up to just you, is it?’

‘She’ll have to know,’ Danny said. ‘Even if he hasn’t asked her, I’m going to tell her. Sometimes he listens to her. She can persuade him to stay at the farm better than I can.’

‘Not much she can do about it from wherever it is she is down south,’ Sarah pointed out. ‘All the same, you’d better write to her. And she’ll want to know all about the new baby. Mam sent everybody a letter to say Ellen had been born but didn’t have time to give any details.’

Danny looked sceptical. ‘That’s more your sort of thing, isn’t it? I don’t know what Kitty will want to know. I’m glad for Rita, of course I am, but all babies look the same to me.’

‘Danny!’ Sarah gave him a straight look. ‘That’s your niece you’re talking about. Honestly, you men, you’re hopeless sometimes.’ Her expression was affectionate though. She could never be truly cross with Danny. He was too good a man for that. She knew he was just teasing – in that special way he seemed to reserve just for her.

‘You tell me what she’ll want to know, then,’ he grinned. He had realised long ago that Sarah knew him better then he knew himself. ‘Better still, write a note and I’ll put it in with my letter about Tommy. That’ll sweeten the pill.’ He grew serious again. ‘Sar, just think of it, young Tommy wanting to put his life on the line like that. I can’t have that. It’s too much. Somehow, we have to stop him.’

CHAPTER THREE

Frank Feeny held the heavy door open for Wren Sylvia Hemsley as they made their way out of Derby House at the end of their shifts. It was unusual for them both to finish work at the same time and he thought they should make the most of it, so earlier when they’d met at tea break he’d suggested going to the cinema. She had said she’d think about it, but wasn’t sure if she would have to stay late to cover for a sick colleague.

Now, though, luck was on their side. Sylvia had been able to get off on time, and they emerged into the early spring evening. Liverpool city centre had taken a pounding earlier in the war and the ruined buildings stood testament to the bombing raids, but also to the indomitable spirit of the people, who had refused to be cowed. At first everyone had been hesitant to walk through the damaged streets, and there had been real danger from falling debris and potholes opening up, especially as there could be no street lighting. They’d got used to it now, though, and the area was beginning to come to life again. The evenings were slowly lengthening and a feeling of optimism was in the air. There had been no major raids over the city for some time, and there was a tangible sense of the tide of war being on the turn. The Allies had won the battle at El Alamein in North Africa and were making inroads into Italy. The attacks by U-boats on vessels in the North Atlantic had dropped considerably, much to the relief of many in the city, whose fathers, sons and brothers sailed that route, as members of the Royal Navy, Merchant Navy or Fleet Air Arm. Frank knew that many of the gains in the North Atlantic were down to what went on in the two levels of basement rooms in Derby House and the nearby Tactical Unit, all plotting the enemy’s positions, working out the best way to intercept and destroy them.

He looked at Sylvia and grinned. They deserved their evening off. ‘What do you fancy seeing?’ he asked.

Sylvia smiled back. ‘How about Casablanca again?’

Frank shrugged. He’d have preferred to go to something new, but Sylvia was a big fan of Humphrey Bogart. ‘I don’t mind,’ he said. ‘It’s on near your billet, isn’t it?’

Sylvia beamed at him. ‘Yes, and we’ll just have time to get there. I’d love to see it again.’ She began to sing as they walked along. ‘Ta da ta da ta … as time goes by …’

Frank raised an eyebrow. Sylvia was a dedicated Wren and highly skilled at her job, very pretty and great company, but even her nearest and dearest couldn’t claim she was musical. She couldn’t hold a tune to save her life. He told himself not to be so judgemental – she had plenty of other fine qualities. But he’d been brought up with music in the house, as Pop was always playing his accordion as they grew up, and many a time he’d taken it down to the Sailor’s Rest and joined in when someone else was on the piano. The children would gather outside and join in the words of any songs they knew. Frank couldn’t remember how old he had been the first time he’d gone along, it was so much a part of his childhood. He had never questioned it – keeping in tune was just what you did. He realised he should count himself lucky that he could hold a note without thinking about it.

Involuntarily his mind flashed back to one occasion when Kitty had been there, singing along in her schoolgirl voice, perfectly in rhythm and in key. She was another one who’d never had to work out how to sing, she just did it naturally. He wondered where she was now – somewhere down south, Danny Callaghan had said, living out in the sticks. Frank gave a small smile. She would hate that.

‘What are you laughing about?’ Sylvia demanded, catching sight of his expression. She turned to face him. ‘Are you making fun of my singing? It’s all right, I know you do that; you’re not the first.’ She sighed. ‘We can’t all be Vera Lynn, or what’s her name, your friend from round here? Gloria Arden. Some of us have to make do with the talents we were born with.’

‘Of course I’m not making fun of you,’ Frank assured her hurriedly. He didn’t want to have a row on this rare occasion of sharing an evening off. ‘One Gloria in the world is quite enough. All right, she’s got a great voice, but she can’t bake a Woolton pie like you can. She never was keen on spending time in the kitchen.’

Gloria Arden was now one of the country’s best-loved singers, riding high in the public’s esteem, her golden voice offering entertainment and comfort in equal measure, and was often to be found touring with ENSA, the Entertainments National Service Association. She’d started her life in Empire Street, though, daughter of the landlord and landlady of the Sailor’s Rest, and had been his sister Nancy’s best friend – still was Nancy’s best friend, in fact, and whenever a tour brought Gloria back to the north of England, she would make a point of seeing her. Even before she made it big, Gloria had never had any domestic inclinations. She’d worked in a factory before she got her lucky break, singing at the Adelphi in the city centre when they had a vacant slot.

‘Bet she can’t mend a uniform jacket like I can either,’ Sylvia went on. ‘Or type as fast.’

‘Or type at all, as far as I know,’ Frank added dutifully. He carefully put his arm around Sylvia’s shoulder – not because he thought she might object, but because he had to be mindful of his balance. He’d lost a leg back in the early days of the war and had used a false one ever since. He could manage most day-to-day things, although his reign as a boxing champion was over, but any sudden movement could be a problem. It meant he couldn’t be as spontaneous as he’d like to be. He’d met Sylvia long after the accident and she’d always said she didn’t mind, but sometimes he wondered. While they were very fond of each other, if pressed he would have to say they were ‘in like’ and not ‘in love’. Then again, he reasoned that the war distorted all relationships. Some couples flung themselves at each other, in case one or both of them weren’t here tomorrow. There had been plenty of over-hasty affairs and marriages, some of which were lasting and others that had already crumbled. Other couples chose to tread much more cautiously, wary of enforced separations or the heightened emotions that inevitably came with prolonged fighting conditions. He suspected that was what had happened to them. Before his accident he had been anything but cautious, but that and the war had matured him, and now he had the added responsibility of being a lieutenant, responsible for training many of the new recruits at Western Approaches Command. He couldn’t be seen gadding about in the streets, even if it was with a highly respected young Wren.

‘Glad to hear it,’ said Sylvia sparkily. ‘I like to know I’m appreciated.’

‘Oh, you are,’ said Frank warmly, and meant it. He brushed her dark curls where they were coming loose from the base of her uniform cap. ‘I’m a lucky man and I know it. It’s not every old crock who has a beautiful young woman on his arm.’

‘Old crock – get away with you.’ Sylvia punched him on the arm. She’d known about his leg from the start and it had never bothered her, though she sensed it still troubled him far more than he let on. All she could do was carry on as normal and hope that one day he’d believe her that it really didn’t matter. He was devastatingly good-looking, he was widely respected at work, and she knew she was the envy of most of the female members of staff at Derby House to be walking out with him. Fair enough, he might not be able to take her dancing at the Grafton, but in all other respects he was just what she’d always wanted. If only he could believe that. Sometimes she wondered if he ever would.

‘Let’s get the bus,’ she suggested, rounding the corner and not even registering the damage to what had once been the large John Lewis department store, so familiar was it in its wrecked state. ‘We don’t want to miss the beginning. That’s the moment I like best – when the lights begin to go down.’ She looked up at him brightly, and winked.

Frank squeezed her shoulder. They halted by the bus stop, busy with workers returning to the outskirts of the city, many in uniforms of the various armed forces. There was a hum of chatter, and Frank thought for a moment how much he loved his home city, with everyone pulling together and getting on with what needed to be done, despite the horrendous bomb damage all around. The people of Merseyside were bigger than the attacks of the Luftwaffe. This is what they were fighting for – the spirit of the place and the people who lived there. He was proud of his uniform, and Sylvia’s, and could see that other people were looking at them approvingly. His earlier qualms seemed unjustified and silly now.

‘Come on, this is ours.’ Sylvia stepped onto the bus and Frank let her choose where to sit. Miraculously there were two seats together, but this was near the start of the route, and later on it would be standing room only. He was secretly glad – he’d of course get up and offer his place to anyone who needed it, but standing for any length of time in a moving vehicle was something he’d rather avoid. As more passengers got on he was pressed closer to Sylvia and he noticed yet again how her cleverly altered uniform jacket curved around her shapely body. No wonder the men in the bus queue had looked at him with envy.

‘What shifts are you on this weekend?’ he asked, his mouth close to her ear as yet another group of passengers squeezed inside. ‘I’m off on Sunday. Shall we make a day of it?’

Sylvia sighed and turned towards him. ‘Oh, Frank, I’d love to, but I didn’t know you’d have any free time. I’ve got both days off for once and I promised I’d go to see my parents. It’s been ages, and they worry if I don’t visit them now and again. They think I’ve wasted away or something.’

‘Ah well, never mind.’ Frank knew that was true. Sylvia came from the Lake District, and even though it was in theory in the same corner of England, the journey was often complicated and took ages. He couldn’t blame her for grabbing the chance to spend some time at home. He was lucky – he only had to travel along the Mersey to Bootle to see Dolly and Pop. He couldn’t begrudge her this opportunity to see the parents he knew she missed dearly, even if she rarely admitted it. He reached down and squeezed her hand. ‘You’ll enjoy that. Give them my best.’

‘I will.’ Sylvia had been nervous at first to introduce Frank and her parents, never fully sure how he felt about her, but after they’d officially been a couple for six months she’d taken the plunge. Of course, they had loved him, and now they never stopped asking her when he was going to pop the question, but Sylvia couldn’t answer that one. If these had been normal times, things might have been different – and yet without the war, she and Frank would never have met at all. ‘Mum will probably load me up with her home-made jam for you.’

‘I’ll use it to sweeten my landlady,’ Frank laughed. ‘It’s about the only thing that works.’ He’d chosen to live in a service billet rather than go back to the little house on Empire Street, as that was already full to bursting, but his landlady was taciturn at best and mostly plain sour. He didn’t complain – he wasn’t there for entertainment.

‘Excuse me,’ said a trembling voice from behind his shoulder, ‘I hate to ask but …’

Frank swivelled round in his seat and saw an old woman, leaning on a walking stick, making her way unsteadily along the aisle. He stood up immediately. ‘Please. My pleasure.’ He took a firm grip of the well-worn metal pole so he wouldn’t embarrass himself by falling as the bus jerked back into action along the potholed road, and the lady sagged in relief as she sat down. Sylvia shuffled along the seat a little to make room.

Frank noticed that slight movement and reminded himself how caring she was and how little fuss she made about it. Some women might have made a song and dance about having to share a seat with someone other than their boyfriend, but not Sylvia. She was simply good-natured like that. She was kind, and very attractive, and she wanted to be with him – so why was he hanging back from committing himself more fully?

‘Is she sleeping?’ Violet leant over the little cot to see Ellen’s tiny face. ‘What beautiful eyelashes she has, Rita. She’s going to be a model in a magazine when she’s grown up.’ She straightened again and tugged at the sleeves of her old cardigan. They must have shrunk again in a too-hot wash, but it was one of the very few she had left.

Rita sat up on the couch, gazing adoringly at her new daughter. ‘She’s been like that for half an hour. I managed to nod off myself, just for a quick nap. I ought to be getting ready for tea but somehow I needed the rest.’

‘Don’t you worry yourself about that,’ Violet tutted. ‘I’ll see to it. You put your feet up while you can. You’ve a lot of rest to catch up on, running round like you did practically until that child was born. Is Ruby minding the shop?’

Rita glanced towards the internal door that led to the shop. ‘Yes, she’s getting better all the time. I think it’s because beforehand she always knew that if things went wrong you or I would be there to sort it out. Now I’ve got Ellen to see to, and you’ve been over at the victory garden, it’s all been down to her. I stick my nose in now and again when you aren’t around, but she’s been forced to speak to people and she’s found they don’t bite after all.’

Violet shook her head in disbelief. ‘It’s been a long time coming, that has. I’ll just put my nose round the door and see if she’s happy with Spam fritters.’ She carefully shut the door to what used to be Winnie Kennedy’s breakfast room, which Rita had turned into a cosy sitting room now her ex-husband’s mother was dead. The once stuffy, over-formal space was now warm and inviting, as Rita had collected scraps of fabric and made patchwork cushions and rag rugs, even if there was no new furniture to be had. She had stored away Winnie’s favoured dark, heavy pieces and kept only the softer, lighter ones, and had begged some tins of paint off Danny Callaghan to brighten the walls and woodwork. Danny, in his former occupation down on the docks, had been able to get hold of the most surprising items, and he still had the odd few tucked away. Usually Rita disapproved; but for this – making a home fit for her new baby – she’d made an exception. Ruby had as much of a claim to the place as she did, but hadn’t objected. Hardly anyone knew but Ruby was actually Winnie’s unacknowledged daughter, but the mean old woman had gone to her grave keeping the secret of who the father was. Charlie had never so much as indicated he’d known this was his sister, either. He’d gone to his own grave despising Ruby as much as Winnie, their mother, had.

Violet pushed open the door to the shop and saw Ruby was out in front of the counter, not hiding in the account books for a change. There was a man there, not young but not elderly either, in a faded brown overall and peaked cap. He looked familiar but Violet couldn’t place him.

‘Oh … oh, hello, Violet.’ Ruby jumped back. She was a little red in the face. Violet supposed it had taken a considerable effort for the shy young woman to talk to the customer, and forgave her the nervousness.

‘Ruby, I’ve just come to see what you’d like for your tea,’ Violet said directly. She turned to the man. ‘I’m sorry, I can’t quite place …’

The man stepped forward and she could now see that he must be about forty. His hair, or what was visible of it, was beginning to grey and he had wrinkles around his eyes, but his expression was friendly. ‘James. Reggie James. It’s Mrs Feeny, isn’t it? My dad told me about you.’

Violet nodded as the penny dropped. This must be the son of old Mr James who’d been so helpful when they’d first started work on the victory garden and hadn’t really known what they were meant to be doing. There behind him were some boxes of vegetables. He must have brought them to be sold in the shop. ‘Very pleased to meet you,’ she said. ‘Your father was very kind to us, you know. We would have been stumped without him. Has Ruby been sorting you out?’

‘Oh … yes. Yes, she has.’ The man seemed suddenly at a loss for words and Violet wondered if he was one of those men who didn’t know what to say to women – some didn’t like to see women running a business, even if it was a corner shop and all the men had been called up or kept in reserved occupations like down on the docks. She noticed he didn’t stand quite straight and wondered why that was. He saw her looking and got in his explanation before she could ask.

‘I was wounded at El Alamein,’ he said, slightly self-consciously, rubbing the top of his leg like a reflex. ‘Some folks think I took a Blighty, but it wasn’t like that. I’d never have dodged my duty by deliberately injuring myself, but it means I can’t go back into active service.’ He smiled sheepishly. ‘I wasn’t as young as most of them and it takes that bit longer to heal at my age, you see. Anyway, now I’m up on my feet again I’m going to help Dad out on the allotment, and do a little sideline in vegetables when I can.’

‘Oh, I’m sure that’s a good idea,’ said Violet hurriedly, a little embarrassed to have been caught staring. She couldn’t imagine for one moment that any son of trustworthy old Mr James could have hurt himself on purpose to avoid further action in the war. ‘We can always sell fresh vegetables, can’t we, Ruby?’

Ruby nodded mutely, seeming to have regressed now that there was someone else to do the talking.

Violet remembered why she’d come in the first place. ‘So, Ruby, Spam fritters for your tea tonight?’

Ruby looked at her feet and then appeared to snap out of it. ‘Yes please. Thank you, Violet.’

‘I’ll leave you two to it then,’ said Violet, turning back towards the living quarters, but not before registering the glance that Ruby exchanged with Reggie James. Then she told herself not to be silly. Ruby had hardly any friends, and sometimes could scarcely say hello to people she’d known for years, she was so withdrawn through sheer habit. She would be far too hesitant to make a new friend of an unfamiliar acquaintance. It must just be that she was pleased with the new business arrangement. Ruby liked the numbers to be in order. That could be the only explanation.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.