Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Cops and Robbers», sayfa 2

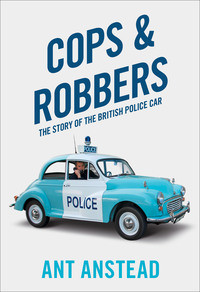

This book was written in order to share not only my passion for the Great British police car but as a nod back to those proud and amazing years I spent serving the British public.

This is a Hertfordshire Vauxhall Astra Mk3 just like the one I started my policing career driving, only mine didn’t have a bonnet box. It wasn’t fast, but it was a faithful servant and I loved it at the time.

CHAPTER ONE

CREATING THE BLUE LINE: THE BIRTH OF THE BRITISH POLICE FORCE

In modern times we take the police for granted, don’t we? Politicians wrangle about bobbies on the beat, budgets or efficiency savings (which even in my time in the force was a euphemism for cuts!), and if a serious crime happens we’re used to seeing the police going about their business on the news. We all know we should pull over for a police car rushing to an emergency on ‘blues and twos’, and we take this sight for granted, because it is now expected that in a civilised democracy we will have a police service that will enforce the rule of law on the criminal few for the good of the law-abiding many.

However, it wasn’t always like this, and although this book will concentrate on the service cars, some background to the police is both instructive and interesting, especially when you learn how the police first dealt with the early motorists on the roads! The story starts long before the famed ‘Peelers’; although they are often seen as the origin of the British police, in fact local areas had, from the earliest days of society, utilised some form of law either by force or consent. The Roman conquest of Britain, which began in 43 AD and lasted until around 420 AD, brought with it a monetary system and a form of organised policing. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms also had a police service of sorts, based on the regional system known as a hundred or (and I love this word) ‘wapentake’. The first Lord High Constable of England was established during the reign of King Stephen, between 1135 and 1154, and those who filled this position became the king’s representatives in all matters dealing with military affairs of the realm.

The Statute of Winchester in 1285, which summed up and made permanent the basic obligations of government for the preservation of peace and the procedures by which to do this, really marks the beginning of the concept of nationwide policing in the UK. Two constables were appointed in every hundred, with the responsibility for suppressing riots, preventing violent crimes and apprehending offenders. They had the power to appoint ‘Watches’, often of up to a dozen men, or arm a militia to enable them to do this. The Statute Victatis London was passed in the same year to separately deal with the policing of the City of London, and, amazingly, today the City of London Police, dealing only with the ‘square mile’, remain a separate entity to the larger Metropolitan Police. The current City Police Headquarters is built on part of the site of a Roman fortress that probably housed some of the London’s first ‘police’, and these ‘square mile’ officers can be distinguished out on the streets by the red in their uniform and by their red cars.

By the end of the thirteenth century the title ‘Constable’ had acquired two distinct characteristics: to be the executive agent of the parish and a Crown-recognised officer charged with keeping the king’s peace. This system reached its height under the Tudors, then the oath of the Office of Constable was formerly published in 1630, although it had been enacted for many years previous to that. Sadly, this arrangement disintegrated somewhat during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and nationally nothing replaced it fully until the Victorian era. However, all police officers still hold the Office of Constable, and when I was appointed as a Constable, in 1999, I too had to take a similar oath in a rather splendid passing-out parade.

London led the way in the development of policing because by 1700 one in ten of England’s population lived in the metropolis, and the population of the area would rise to over a million before the century was out. Sir Thomas de Veil, a silk merchant-turned-soldier-turned-political lobbyist, became a Justice of the Peace in 1729 and worked out of his office in Scotland Yard. He conducted criminal hearings, moving to Bow Street in 1740, and as the first magistrate to set up court there effectively created the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court. His ideas for curtailing crime were ambitious, and, following his death in 1746, the novelist Henry Fielding was appointed Principal Justice for the City of Westminster in 1748 together with his brother, Sir John Fielding. They appointed a group of ‘thief takers’ as they were initially called, who were paid a retainer to apprehend criminals on the orders of the magistrates. These men soon became known as the Bow Street Runners; by 1791 they had adopted a uniform, and by 1830 over 300 officers were based in Bow Street, some using horses in the battle against crime.

A similar process happened in Scotland, where the first body in Britain to actually be called a police force was set up by Glasgow magistrates in 1779. It was led by Inspector James Buchanan and consisted of eight officers, but by 1781 it had failed, through lack of finance. However, the force was revived in 1788 and each of its members was kitted out with uniforms with numbered ‘police’ badges on, in return for lodging £50 with magistrates to guarantee their good conduct. The force of eight provided 24-hour patrols (supplementing the police watchmen, who were on static points throughout the night) to prevent crime and detect offenders. Their list of duties, which would fit comfortably into the basic duties of policing today, included:

• Keeping record of all criminal information.

• Detecting crime and searching for stolen goods.

• Supervising public houses, especially those frequented by criminals.

• Apprehending vagabonds and disorderly persons.

• Suppressing riots and squabbles.

• Controlling carts and carriages.

Thus Glasgow had established the concept of preventative policing, and it’s hard not to wonder just how much knowledge of this Robert Peel had or how much inspiration he perhaps took from Glasgow’s pioneering force when he brought this idea into Parliament forty years later. On 30 June 1800, the Glasgow Police Act 1800 received Royal Assent, and John Stenhouse, a city merchant, was appointed Master of Police in September 1800. He immediately set about organising and recruiting a force, appointing three sergeants and six police officers and dividing them into sections of one sergeant and two police officers to each section – to some extent copying military practice while also pioneering a line of command that is not unfamiliar today.

However, in order to understand the history of policing in England we must also look at the most efficient freight vehicles of the eighteenth century – boats. The modern police service has its roots in a river security force that was set up by Patrick Colquhoun in 1798. He persuaded fellow merchants to pay into the scheme, which was designed to combat the epidemic of cargo thefts in the Pool of London (a stretch of the Thames), and which, in 1799 remember, amounted to over half a million pounds. The area was so congested it was said to be possible (most of the time) to walk across the Thames simply by stepping from ship to ship. The government absorbed this service in 1800 and renamed it the Thames River Police.

When reformist Robert Peel (whose Christian name is the reason why police are still commonly referred to as bobbies) became Home Secretary in 1822, his initial attempts to create a national police force failed. However, he succeeded in putting through the Metropolitan Police Act in 1829, creating a force with just over a thousand officers. Peel was determined to establish professional policing in the rest of England and Wales, and the Special Constables Act of 1831 allowed Justices of the Peace (JPs) to conscript men as special constables to deal with riots, and this was built on by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which established regular police forces under the control of new democratic boroughs, 178 in all. It was not a great success and was often ignored; however, the later County and Borough Police Act 1856 built on the idea, committed proper financing and decreed that a rural police force was to be created in all counties; it was one of these, the county force of Hertfordshire, that I joined.

At this point in history there was still a way to go to achieve the police force that we have today, but the beginnings of our modern policing system could be seen in the counties and in Glasgow. By the 1860s a nationwide force of separate bodies acting to one set of rules and connected by transport links (horse-drawn initially, but increasingly using the railway system, which was expanding rapidly by 1850) existed. The car would eventually be invented in 1885, but police forces all over the world simply weren’t ready to manage this new and politically divisive mode of transport. Britain was no exception.

The Office of Constable: the basis of UK policing

On appointment, each police officer makes a declaration to ‘faithfully discharge the duties of the Office of Constable’, and all officers in England and Wales hold the Office of Constable, regardless of rank. They derive their powers from this and are servants of the Crown, not employees. The oath of allegiance that officers swear to the Crown is important as it means they are independent and cannot legally be instructed by anyone to arrest someone; they must make that decision themselves. The additional legal powers of arrest and control of the public that are given to them come from the sworn oath and warrant, which is as follows:

‘I do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that I will well and truly serve the Queen in the office of constable, with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, upholding fundamental human rights and according equal respect to all people; and that I will, to the best of my power, cause the peace to be kept and preserved and prevent all offences against people and property; and that while I continue to hold the said office I will to the best of my skill and knowledge discharge all the duties there of faithfully according to law.’

This is the oath that I myself took.

CHAPTER TWO

THESE DEVILISH MACHINES SCARE THE HORSES, YOU KNOW

On Monday 20 January 1896, Mr Walter Arnold, who worked for his family’s agricultural machine-engineering concern in East Peckham, Kent, was driving along the Maidstone Road through the neighbouring village of Paddock Wood at an estimated 8mph, 4mph or so below the maximum speed of the ‘Arnold Motor Carriage Sociable’ (a Benz copy produced under licence) that he was driving. Local constable J.C. Heard, of the Kent County Constabulary, saw this outrageous behaviour from the front garden of his cottage and set off in hot pursuit on a single-speed bicycle. In that one moment the relationship between the UK police and the motorist was, partially at least, set.

The speed limit in the area was a mere 2mph, so Arnold was thus exceeding it fourfold – although how Constable Heard measured this accurately enough to definitely state this is, of course, unknown. Arnold was chased (on the bicycle) and eventually caught by the presumably quite fit local bobbie after a five-mile pursuit! It is recorded, with some understatement I suspect, that Constable Heard had to pedal at his hardest for quite some time (at 8mph that’s just under 40 minutes’ pedalling time) before catching the unfortunate Mr Arnold. Arnold was charged with four offences; three pertaining to the Locomotives Act and one offence of speeding. The case went to trial, and although Arnold’s barrister, a Mr Cripps, argued that the law shouldn’t apply to the new lightweight ‘autocars’ and that Arnold had a carriage licence (a system designed for horse-drawn carriages), Arnold was found guilty on all counts and ordered to pay a total fine of £4 6 shillings, of which only a 1 shilling fine and 9 shilling costs was for the speeding offence. When you take into account that his car sold for £130, this fine seems quite paltry, but remember that cars back then were a luxury, and the average weekly wage was less than £1 for a 56-hour working week.

Arnold was not only the first motorist fined for speeding in the UK, but it is believed that he was the first person in the world to claim this dubious honour. The car as a concept was young, and, much like laws surrounding the internet in the early twenty-first century, the legislators took some time to draft new laws that applied to these vehicles. Some eminent politicians of the time even felt it wasn’t worth the bother, as they deemed that these horseless carriages were bound to be just a phase, the attitude being that they would be short-lived as they frightened the horses for goodness sake!

Arnold probably wasn’t too unhappy with the publicity that his case generated, because he was in fact one of the country’s first car manufacturers and dealers. His career began by selling new, imported Benz cars from Germany, then between 1896 and 1899 he manufactured a licensed copy of the Benz called the Arnold Motor Carriage. At this point demand for these newfangled machines was high and Arnold is quoted as saying in a newspaper report towards the end of 1896 that, ‘if we had twenty in stock they could be disposed of in a week’. No documents exist hinting in any way that he deliberately drove through Kent intending to get caught, but you have to wonder, don’t you? If he did do it deliberately he was a marketing genius and well ahead of his time. He apparently sped past the Constable’s house, and as a local himself he would surely have known where the local bobbie lived. If he did get caught deliberately, he exhibited an understanding of the media and the gentle art of car marketing at least fifty years ahead of his time – secretly, I kind of hope he knew exactly what he was doing, and thus Arnold placed down a permanent marker for all car sales people to follow. Take a bow, my man.

Arnold kept a scrapbook of press cuttings about his cars and their exploits that still belongs to the owner of the very car that he was driving when he was apprehended, so it’s a real possibility that this was a deliberate act. Having said that, that scrapbook also shows that he and other family members committed similar offences at least twice more, so perhaps they just considered this the price paid for the freedom to ‘motor’ at will. This was certainly the prevailing wisdom among motoring pioneers of the time, and the pages of the first editions of The Autocar (which began circulation in 1895) are full of motorists testing the judicial system in one way or another, using their new machines. Newspapers also picked up on this, carrying drawings of ‘future townscapes’ showing horseless carriages and stating that science had made this possible but the law was preventing it happening.

Arnold Motor Carriage Sociable, Chassis Number 1, MT20

Engine: 1200cc single cylinder with open crank case and separate water jacket.

Power: 1.5bhp@650rpm.

Range: 60–70 miles on one tank of ‘Benzoline’ oil, as early petrol was called. This cost 2s 6d per gallon in 1896.

Ignition: Electric, with enough current stored in two 2-volt accumulators to run the car for approximately 600 miles. The concept of a charging system was not initially included.

Max speed: Approximately 12mph, able to average 10mph comfortably.

Transmission: Fiat belt with movable bearings to take up slack.

Production: 12 examples made between 1896 and 1898, plus a small number of related vans.

After being development-tested in Ireland in order to avoid further persecutions by the local constabulary, Arnold Number 1 was sold to engineer H. J. Dowsing and became the first car ever fitted with an electric starter motor, called a Dynomotor. Amazingly, this was originally designed as an electric ‘help motor’ to give the car greater power when needed for hills. Yes, the concept of the petrol-electric hybrid so trumpeted by the Toyota Prius in recent years was in fact invented in 1897 by Dowsing, although its development was not pursued at that time.

Remarkably, this original car has still only had five owners from new: the Arnold Company, Dowsing, a Captain Edward de W. S. Colver, RN (Rtd), who partially restored the car after buying it from Dowsing in 1931 and whose family sold the car to the Arnold family at auction in 1970. In the mid-1990s it was sold to Tim Scott, who retains ownership today and uses it regularly on the London to Brighton run and other events.

With pollution from cars a regular topic in the TV news, and even a consideration in political campaigning, it seems counter-intuitive to say that the car was bound to catch on because it was so much cleaner than the alternative, but that’s exactly what happened. The alternative, which had existed for many years, consisted of wading through a horse-manure-based, and extremely pungent, soup. Period dramas on TV skim over this, but it was definitely a factor in the growth of motor-car use, and compared to getting horse manure all over your skirt or trousers, car exhausts must have seemed amazingly clean and green!

However, UK legislation initially made the technical and physical progress of mechanised transportation difficult, whether powered by gasoline (the word petrol did not enter use until it was patented by Messrs Carless, Capel and Leonard of Hackney Wick in 1896), steam, electricity or even coal dust. In 1865 the Locomotive Act (Red Flag Act) had introduced a speed limit of 2mph in towns and villages and 4mph elsewhere. It stipulated that self-propelled vehicles should be accompanied by a crew of three: the driver, a stoker, and a man with a red flag walking 60 yards ahead of each vehicle. The man with a red flag or lantern (when dark) enforced a walking pace, and warned horse riders and horse-drawn traffic of the approach of a self-propelled machine. After centuries of animal training and use, both the politicians and general population trusted a well-trained horse far more than these newfangled steam-driven road locomotives!

Parliament thus effectively framed legislation that trusted the established system, horse-drawn wagons, and prevented the scaring of horses, which were then the backbone of commerce. The country’s legislators put more trust in the behaviour of horses than in the safety of human-designed and built machinery … This seems amusing to modern sensibilities, but perhaps they were right to create these laws, for these early machines weighed an enormous amount, had little in the way of brakes and made all sorts of scary clanking and hissing noises which could spook even the best-trained horse. However, the development of smaller petrol and electric carriages made this law outdated by 1890, and it was this law that was most often tested by pioneer motorists who claimed they could use an Autocar on a standard (horse-drawn) carriage licence rather than the much more restrictive Locomotive Licence. Arnold also claimed this and was convicted of this offence as well as speeding. This Arnold chap is my type of guy. I like to think we would have been friends.

Although the use of motor cars was growing in the 1890s, the horse was king and would effectively remain so (at least in volume terms) until after World War I, which was, like so many conflicts, the catalyst that drove change technically, economically and socially.