Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

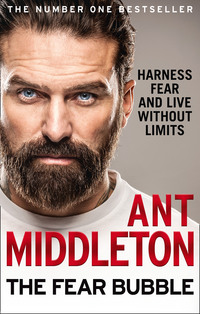

Kitabı oku: «The Fear Bubble»

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

SECOND EDITION

© Anthony Middleton 2019

Cover design by Clare Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Cover photograph © Andrew Brown

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Anthony Middleton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008194680

Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008194697

Version: 2020-03-06

DEDICATION

For my wife and children, who have been there for me without fail: Emilie, Oakley, Shyla, Gabriel, Priseïs and Bligh. You give me the driving force to become the best version of myself and to want to succeed at everything I do. You really are my everything. Never forget that.

CONTENTS

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 PROLOGUE

7 CHAPTER 1: TAMING THE GHOST OF ME

8 CHAPTER 2: HOW TO HARNESS FEAR

9 CHAPTER 3: THE ROAD TO CHOMOLUNGMA

10 CHAPTER 4: THE MAGIC SHRINKING POTION

11 CHAPTER 5: IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE LANKY BEEKEEPER

12 CHAPTER 6: THE FEAR OF SUFFERING

13 CHAPTER 7: THE ICEFALL

14 CHAPTER 8: THE FEAR OF FAILURE

15 CHAPTER 9: DEATH IS OTHER PEOPLE

16 CHAPTER 10: THE FEAR OF CONFLICT

17 CHAPTER 11: CONQUERING THE KING OF THE ROCKS

18 CHAPTER 12: EVERYONE’S SECRET FEAR

19 CHAPTER 13: REVENGE OF THE KING

20 CHAPTER 14: THE OPPOSITE OF FEAR

21 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

22 By the Same Author

23 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivv12345789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585961636465666768697071727374757677787980818283848586878889909192939495969799101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191193195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213215217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237239241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257259261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343ii

PROLOGUE

There were ten of us up there, single file up a narrow track of rock and ice. The going was hard, the incline steep. We’d been up and out of our sleeping bags since dawn, with heavy daypacks strapped to our backs, and were hungry and thirsty and tired. Toes were sore and fingers were numb. The freezing air dried our mouths. I’d never been so high off the ground. The climb was such that we were half-crawling, ankles bent, hands grabbing at anything that looked as if it might take our weight. There wasn’t much time to look around and take in the view, but with every glimpse upwards I took I could sense the world getting bluer and bigger around us as the sky swelled into a high dome. With every movement of arm, leg and lung, we were leaving our everyday lives further behind and inching higher into the heavens. It felt rare and unsettling.

The further we climbed, up towards the mountain’s famous pyramidal peak, the thinner the track became and the slower the going. Nobody was talking any more. There was no laddy banter or gruff words of encouragement among the men, only grunting and panting and the silence of intense concentration. As I pushed on, I kept reminding myself that we were walking in the steps of my mountaineering hero Edmund Hillary, who’d penetrated these glacial valleys, known hereabouts as ‘cwms’, and scaled these icy cliffs more than six decades ago. We were way above the birds, it seemed, intruding into the realm of the gods and playing by their rules. I tried not to focus on the height or the danger, although I could feel the fear as a kind of tense sickness in my gut. This was getting serious. A couple of steps to the right and you were off the mountain. Dead.

A crack. A cry.

‘Shit!’

A rock the size of a cannonball flew past my face, missing my jaw by about half an inch. It was so close I could smell its cold metallic tang as it shot by. I lurched out of the way, skidding on the track, almost following the rock down. Above my head a brown boot scrabbled on the snowy scree for purchase. I looked down to see the rock being swallowed by the abyss, smacking and echoing as it bashed down the mountainside. An icy wind blew around my neck and face.

‘You all right?’ I shouted up.

The lad above me was gripping on to the mountainside, as if the earth itself were shaking. His cheeks were pale, his shoulders slumped, his gaze rigid.

‘Yeah,’ he said. And then, with a little more assurance, ‘Yes, mate.’

I watched him steel himself and try swallow his dread. He turned to carry on.

‘Good man.’

He lifted his leg once again, trying to find a more secure foothold. But then he paused, his boot hovering mid-air. He sucked in tightly through his chapped lips, breath billowing out.

‘I’m coming down,’ he said. ‘It’s, er … I’m, er …’

I thought he was going to lose it. His breathing became rapid and he started looking all around him, as if surrounded by invisible buzzing demons.

‘Just take it slow,’ I shouted up.

As he picked his way past me, I pressed my body into the freezing incline. His fear was infectious. I wanted so badly to go with him. It was safe down there. There was tea and biscuits and shelter. What the fuck was I doing up here? What was the point? What was I trying to achieve? The mountain didn’t want us crawling up it like fleas, it was making that all too obvious. It was trying to shake us off, one by one. Who was I to think I could take it on? Who was I to think I could succeed where Hillary himself had struggled? How was I supposed to know where to put my feet? The guy in front of me had placed his foot on a rock that looked like it had been rooted in place for a thousand years, and it had nearly made him fall off the mountain and taken me with him.

‘What you doing, Midsy?’ came a frustrated voice from below. ‘Come on!’

I had to make a decision, one way or the other. I had to commit. Up? Or down?

Up.

I pushed myself back into a climbing position. The instant my body followed my mind’s instruction, something incredible happened. The entire mountain changed. It wasn’t trying to shake me off any more – it was pulling me towards it. Every rock had been put there, not to trick me, but to help me. When they worked loose from the mountainside and gave way, that wasn’t the mountain trying to kill me, that was the mountain telling me where not to put my feet. These icy gullies weren’t death slides, they were ladders. Look how beautiful it was up there. I’d never seen anything like it. I’d never felt anything like I was feeling, right then. I would achieve this. I would fight the fear. I would use it like fuel. I would make it up there, to the top of the world, to the seat of the gods. I would conquer heaven.

CHAPTER 1

TAMING THE GHOST OF ME

Twenty Years Later

‘Light?’

‘Cheers, buddy.’

I took a few rapid, light puffs of my cigar and heard it crackle into life between my fingers. The smoke that licked the back of my throat was rich and smooth, almost spicy. I took a deeper draw and peered at its glowing end. You could taste that it was expensive. But was this really £400 worth of cigar? That would make it, what, five quid a puff? I settled more deeply into the leather club chair and drew again, this time luxuriating in the experience, allowing the smoke to slide out through my lips gradually and wreathe about my face in silky ribbons. Before it dissipated, I took a sip of the rare single malt whisky my new barrister friend Ivan had also bought me, this time at the bargain price of £60 a shot.

‘So, how are you enjoying your new life?’ he asked me, his accent as cut-glass as the tumbler in my hand.

His wry expression told me he probably wasn’t expecting an answer. After all, wasn’t it obvious? To all outward appearances my new life was going brilliantly. I’d seen my face on billboards, and my latest TV show Mutiny had been broadcast to millions of viewers and enjoyed critical acclaim. If that wasn’t enough, I was in the middle of a sold-out tour of the UK. Every night, in a different town, I’d spend a couple of hours on stage, talking thousands of fans through some of my favourite moments, not just from Mutiny but from two series of SAS: Who Dares Wins. I’d then be whisked away in a black Mercedes with tinted windows to a five-star hotel where an ice-cold beer and twenty-four-hour room service were waiting for me.

And here I was being wined and dined by a top barrister in one of the most exclusive and secretive private members’ clubs in the world. If you’ve not heard of 5 Hertford Street, it’s because the owners like it that way. If you walked past it, you wouldn’t know it was there. It’s set in a warren of closely packed streets in Shepherd Market, Mayfair, a corner of the capital that used to bristle with high-class vice and scandal but now, aside from a red light bulb or two that shines out of an upstairs window, is polished and prim and postcard perfect. Downstairs, I could hear the faint bass throb of music coming from Loulou’s, its nightclub. Next door, the beautiful faces of London high society ate Sicilian prawns or duck with broccoli in the restaurant, their scrubbed and trimmed dogs at their side. This was where billionaires, moguls and the aristocracy of both Hollywood and Britain’s most gilded families went for their Friday-night drinks. And tonight I was among them.

‘So, you’re enjoying it, I take it?’ Ivan asked again.

‘What’s that?’ I said.

‘Is everything all right, Ant? You’re miles away.’

‘Oh, sorry, bud,’ I smiled. ‘Yeah, it’s not bad. It’s OK. I’m bedding in.’

Ivan was one of the elite. He fitted right in to this place, gliding over the sumptuously patterned carpets and past the heavy, gilt-framed paintings with graceful ease. The fact was, with his blue pinstriped Turnbull & Asser suit, his wide pale yellow tie rakishly unknotted and his long fringe swept back, he’d have fitted right in anywhere in the monied world – London, Singapore, Frankfurt or Dubai.

‘Well, yes, I can quite imagine,’ he said. ‘It must be a rather different experience being entertained here than it was back in the mess.’

‘The mess?’

‘That’s right, isn’t it?’ He swirled the golden liquid in his glass and absent-mindedly watched the lights dance across its surface. ‘In the military. Where you ate. The mess. That is what you call it? I’ve always thought that rather odd.’

‘Why odd?’

‘Well, it’s a joke, I take it. Irony. Military humour.’ His eyes flicked up. ‘I mean, you know, are they messy places? One would rather imagine not.’

Between us there was a small mahogany table on which sat a heavy, polished-iron ashtray in the shape of a leaf. I tapped my cigar onto its edge and found myself mentally weighing it. It was big. Hefty.

‘It’s French,’ I told him. ‘From the word “mets”, meaning a dish or a portion of food. It’s not because it’s …’

‘Oh, is that so!’ he said, laughing. ‘Of course. Yes, I should have known. Yes, yes, how silly of me. The French.’ He kind of half-winked in my direction. ‘That was an impressive stab at a French accent there, by the way, Ant. It felt, just for a moment, as if I’d been whisked away to the harbour at St Tropez.’

Yeah, that ashtray had to weigh a good three or four kilos. Maybe more. You could do some proper damage with that. Put a door in. In fact, you could put someone’s head in with that thing. Easily. I’d use the bottom edge. Curl my fingers into the bowl, get some proper purchase on it and wear it like a knuckle-duster. Wallop.

‘I grew up in France, as it happens,’ I told him.

‘In France? Well, I never. Whereabouts?’

‘So I’m fluent in French.’

‘Well, bravo,’ he said, raising his glass. ‘Cheers to you. And I do hope we can come to some arrangement over this company retreat in April. We’ll fly you in first-class. It would be a real morale booster for the firm to have you come along and speak to the troops, even if they’re not of quite the same physical calibre as the troops you’re used to working with. Although, saying that, some of the chaps and chapesses in the office are terribly into the fitness scene – it’s quite impossible to get them out of the gym at lunchtimes. But it gets harder as you get older, doesn’t it? I expect this new phase of your career has come at just the right time for you. Even if you do miss the military life, when you get to our age, it’s … I mean, you’re clearly in very fine shape. I try to keep in reasonably decent order myself. But the selection process. The SAS. Do people our age do it? People in their forties?’

‘Ivan, mate, I’m thirty-seven,’ I said.

‘Of course you are. I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to imply … Of course you could still pass Selection. You’d fly through it. You’ve only got to see your television programmes …’ He was beginning to bluster.

‘Ivan, mate, it’s totally fine,’ I said, laughing. ‘Forget it. Fucking forties! What are you like?’

As he relaxed once again, he began telling me about his own fitness regime. No carbs after 6 p.m., forty-five minutes in his home gym three times a week, a personal trainer called Samson. As I listened, enjoying my cigar, I found myself beginning to wonder, what would happen if it all kicked off in a place like this? What if Isis came through the door? A lone shooter or a guy in a bomb vest? What would Ivan do? How would that waiter over there respond? Rugby tackle him? Go for his legs? Or shit himself and dive under the table? I scanned the people around me. They’d go into a flat panic. Every single one of them.

I know what I’d do. I’d head-dive into cover, down there in the corner, and then I’d come around and try to disarm him. I’d use the ashtray as a weapon. I’d crack it right over him. Right around the fucking face. Smack. Cave in his cheekbone and then go straight into a backswing, push his chin up into his nose. God, I would love to see it kick off in here. That old geezer in the corner in the bow tie just turning around head-butting that fat dude with the pink hanky in his top pocket – landing it perfectly between the eyes, knocking the cunt into the fire. That woman in the lily dress giving the terrorist a proper crack in the jaw, bursting his nose open with that massive jewel on her finger. Some old Duke being kicked down the stairs by a minor royal in stilettos. Yes. Yes! What would it take for this place to go up? I would pay good money to see that.

‘To success!’ said Ivan. Suddenly, I was back in my body. The room instantly reorganised itself back into its hushed, murmuring and peaceful state. There was no blood on the walls or scalp on the carpet. The stairs were empty of violence. I was no longer crouched on that £10,000 rug de-braining a terrorist.

‘Success!’ I replied.

I raised my glass and downed it all.

Success. Is this what it was? Warm rooms and expensive dinners? Small talk with top barristers about personal fitness and fat cheques for corporate events? An hour later, as I strode down to Green Park tube past pubs and art galleries and dark human forms hurrying along the wet pavements, I found myself brooding. When I left the Special Forces in 2011, I had no idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life. What could I possibly achieve that would be better than the buzz of leading a Hard Arrest Team in the badlands of various war zones over two intensely frightening and violent tours of duty? Life back home in Chelmsford, I quickly discovered, was not like life in Helmand Province. I found it difficult to adjust, ending up physically assaulting a police officer and serving time in prison. The easiest thing I could have done, when I hit those lows, was to join my friends and associates in their criminal gangs. It wasn’t as if they hadn’t tried hard and repeatedly to recruit me. Someone with my background, I knew, had enormous value to those kinds of organisations – and I’d be handsomely rewarded. I would certainly have ended up wealthier than I was now. And the excitement? Oh, that would have been there, no doubt about it.

As I reached the end of the dark, narrow corridor of White Horse Street, a young couple were walking in my direction. The girl, her pale face framed in a white parka hood, gave a slight double-take when she saw me. I hunched my shoulders and sent my gaze to the floor. Please don’t ask for a selfie. Not now. When they were safely in the distance I went to cross the road and waited at the kerb. The usually busy lanes of Piccadilly were at a rare lull. I looked left and then right. There were a couple of double-decker buses, one coming in each direction, both trailing a stream of taxis and vans behind them. I waited. And then I waited some more, allowing them to get even closer. At the final instant, just as they were about to roar past my face, I darted out, dodging one and then the other, feeling their fumes billow around me as I danced between them.

I knew only too well why so many former Special Forces operators ended up either on the street, traumatised and addicted, or working for a criminal firm. Because success in civilian life lacks something that we’ve come to crave. You can’t take it out of us. It’s in there for life. And it’s not the fault of the military training, either. You can’t blame that. The fact is, we’re simply those kinds of men. We exist on that knife edge. Go one way, they’ll end up calling you a hero, a protector of the public and the nation. Go just a little in the other direction and you’ll find yourself in prison, an enemy of the same public and the same nation. The extreme forms of training that admittance into the Special Forces demands don’t cause us to be these kinds of people. It just takes what’s already there, hones it, draws it out and teaches us to control it. The problem is, this quality doesn’t simply evaporate when you leave the SAS or, in my case, the SBS. It’s still in there. It’s in your blood. It’s in your daydreams. It’s in how you walk. It’s in the way you scan a room the moment you enter it, looking for entry and escape routes, pockets of cover and potential aggressors.

And it’s also in how you cross the road. I’d noticed myself doing that increasingly over the last few weeks. If I was in London, or in one of the traffic-choked streets in the centre of Chelmsford, and I saw a pedestrian crossing with the green man flashing, I wouldn’t run to catch it like everyone else. I’d slow down. I’d wait until the traffic was fast and raging again, and only then would I cross. I’d never do this in front of my wife Emilie and certainly not in front of my kids. To be honest, I was only half-conscious of doing it myself. I hardly even knew how to explain it, apart from to say that it was that edge I was after, that edge I would go looking for anywhere – a brief moment of danger to keep my heart beating and my spirit alive. That threat, that trouble, that fear. I was constantly looking for opportunities to push myself, test myself and add a little dose of risk to my otherwise overwhelmingly safe days.

So that was it. That was why Ivan had provoked a host of strange and uncomfortable emotions to come bubbling out from deep within me when he’d asked if I was enjoying what he called my ‘new life’. Of course I enjoyed its trappings. Who wouldn’t? It felt great to achieve so much in these areas of popular culture that I’d never have even dreamed of entering just a few years ago. You couldn’t deny I was successful. But this wasn’t my kind of success. I felt as if I were somehow losing my identity. And the problem was, my identity was beginning to fight back. I could feel it punching and kicking, whenever I was in meetings with guys like Ivan or in places like 5 Hertford Street. The warrior inside me would rise out of nowhere and take over my thoughts. I’d find myself daydreaming about terrorist attacks or mass brawls breaking out, building my strategy for dealing with the madness, assessing everyone around me in terms of how much of a threat they’d be and how I could take them out. This could happen to me anywhere – in the ground-floor canteen at Channel 4 or on the set of This Morning, waiting to be interviewed by Phil and Holly in front of millions of viewers. It was like I was being possessed by the ghost of the man who used to be me. And the really worrying thing was, these weren’t waking nightmares that left me in cold sweats. They weren’t PTSD-like moments of dread and horror. They were fantasies. I was willing them to happen.

After the deep orange darkness of London’s November streets, the lights inside Green Park tube station felt too bright, and I squinted a little as I ran down the long flights of stairs towards my platform, racing the people descending the escalators on either side of me. I found a quiet seat at the end of a carriage and jammed my hands into the pockets of my jacket. A few seats away from me a couple of girls sat opposite each other. They looked to be in their early twenties, and were giggling and laughing in that drunk schoolgirl way. One had taken her high heels off, and her bare toes were now blackened from the tube floor. An unopened bottle of WKD Red stuck out of her lime-green handbag. Another, open and half drunk, was clutched in her hands. The other girl wore a tight white mini-dress and had a tattoo of Michael Jackson on her arm. Her faux leather jacket lay on the seat beside her, along with their crumpled Burger King wrappers and boxes.

When I stepped into the carriage they’d been cackling loudly, but once they clocked me they fell into a hushed chatter, interspersed by periodic piggy, nasal snorts of laughter.

‘Here we go,’ I thought. ‘I’ve been spotted.’ But then I checked myself. Maybe not. One of the things about finding yourself unexpectedly well known – among certain parts of the general public, at least – is that it’s easy to become paranoid. You start to think that everyone’s watching you, wherever you go, even though most members of the public would never have even heard of you. Anyone who’s been on the TV for more than ten minutes has an embarrassing story to tell about a stranger coming up to them in the street, and them presenting their finest prime-time Saturday-night smile and preparing to quickly scribble out an autograph, only for that person to ask if they know the directions to the nearest McDonald’s.

The girls were now leaning into each other and whispering intensely. I wondered what they were they doing. Plotting their next assassination? I kept noticing their eyes swivelling out from their dark huddle and looking in my direction. Then they abruptly sat back, now not saying anything. Suddenly a phone appeared. It was in a black case with Michael Jackson picked out in fake diamonds, one hand on his trilby, the other on his crotch. The girl in the mini-dress was holding it directly in front of her face, but some distance away from her, like an old lady squinting at a book. Then it turned slowly in my direction. The girl looked upwards, now apparently closely examining the advert for student home insurance above the window opposite her. There was the faint electronic sound of a shutter being clicked. Her mate snorted with laughter. ‘Shut up!’ the first one hissed.

I wouldn’t mind if they’d asked. I never complain about being recognised or having to pose for selfies, as that would be ungrateful and disrespectful. And I’d hate – more than anything – to be perceived as being rude to anyone. Having said that, I always try to keep my head down when I’m out and about. I never pretend that I’m someone. I hate being in that mindset, thinking that I’m the centre of attention. But more and more, things like this kept happening. I’d leave the house and be reminded very quickly that my existence had changed. There wasn’t much I could do about it. This was the reality of the ‘new life’ that Ivan had been asking about.

It was a life that didn’t come without its own peculiar risks. I only had to walk out of a pub looking unsteady and some newspaper somewhere would print a story that I was an alcoholic. I only had to scowl in someone’s direction and it would be reported that I was in the middle of a heated argument. So I needed to make sure that my behaviour in public wasn’t merely immaculate – it could never even be perceived to be anything less than immaculate, even down to the expression on my face.

Maintaining that level of good behaviour wasn’t easy, especially for someone with a past like mine. It wasn’t a comfortable combination, all those eyeballs, all that stress – and my personality. The more I felt watched, the more that old, raucous version of me wanted to kick back. The intense pressure to behave immaculately – in trains, on the street and within private members’ clubs – taunted that unstable ghost living inside me. It goaded him and mocked him and motivated him to take me over. I felt him writhing around, pushing at me, tempting me to make chaos. As the girl took another photo, and this time barely bothered to pretend she wasn’t, I buried my fists deeper into my pockets and pushed my chin into the collar of my coat, as my left leg bounced up and down in nervous, aggravated motion. ‘I should’ve got a car back,’ I thought to myself. ‘Fuck this. I’m not taking the tube any more. I’m going to stop taking public transport.’

By the time I got to Liverpool Street station I’d done a lot of serious reflecting. What on earth was I thinking? Who was I turning into? Some TV celebrity puffing on £400 cigars who refuses to go on the underground? In that moment with the girls and the photos, it felt as if everything I was, everything I’d fought so hard to become, was at risk of getting lost. I didn’t want to fall head first into this new life, with its new definition of success. It wasn’t just that I was worried I’d change for the worse and become some spoiled ‘celebrity’. I was afraid that if I didn’t grab hold of the situation, the old me would fight back in a way that I couldn’t control. There was a genuine danger that I would revert to finding my buzzes elsewhere. That could be drinking. That could be fighting. That could be getting myself killed by a double-decker bus. Too many people were relying on me these days for that to happen. It wasn’t only my wife and five children. My life had somehow turned into a small industry. There were teams of people making serious parts of their livelihoods off the back of me, and all of them needed me out of prison and off the tabloid scandal pages, not underneath ten tonnes of steel and rubber in the middle of Piccadilly. My success and theirs were intertwined. I felt a responsibility to every single one of them.

But what could I do? How could I exorcise this ghost when I had all these eyeballs on me? Perhaps I could take a spell out of the limelight and go back to West Africa, where I’d carried out some security work before life in the media found me. That might be fun – I’d get into some interesting scrapes – but there was no way I’d get it past Emilie. It was too sketchy. I thought about running a marathon or taking up boxing in a serious way, but neither of these would really test me. I needed that perfect balance, somewhere I could feel fear but actually be relatively safe.

As soon as I had that thought, an incredibly vivid memory came to me. It was so powerful it was like being in a momentary dream, one that took me back all of twenty years, when I was seventeen. It was my first adventure training package in the army, and we’d climbed Snowdon in Wales. Before that day, during basic training, my life in the military had been extremely controlled. We’d been spit-polishing boots, doing drills and press-ups and running around in the mud, all under the instruction of barking troop sergeants, with almost every minute of every day being tightly regimented. Even though I’d been pushed to my limits, it had all been done in an environment of safety. I’d been scared and intimidated, but the only things I’d really had to fear were failure and humiliation – threats to my feelings. It had been fake danger. And then we’d climbed the mountain.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.