Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

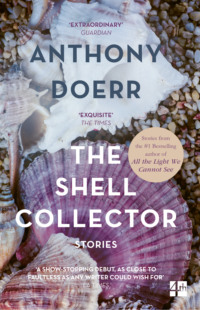

Kitabı oku: «The Shell Collector»

The Shell Collector

Anthony Doerr

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by Flamingo 2002

This eBook edition published by 4th Estate 2016

Copyright © Anthony Doerr 2002

Anthony Doerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

This collection of stories is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All but one of the stories in this collection have appeared elsewhere, in slightly different form: ‘The Hunter’s Wife’ in Atlantic Monthly; ‘So Many Chances’ in the Sycamore Review and Fly Rod & Reel; ‘For a Long Time This Was Griselda’s Story’ in the North American Review; ‘July Fourth’ in the Black Warrior Review; ‘The Caretaker’ in the Paris Review; ‘A Tangle by the Rapid River’ in the Sewanee Review; and ‘The Shell Collector’ in the Chicago Review.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007146987

Ebook Edition © December 2011: 9780007392469

Version: 2018-09-13

Praise

‘These complex, resonant, beautifully realised stories sing. An entire world unfolds in each, memorable and rich; together, they form a remarkable first collection.’

ANDREA BARRETT, author of The Voyage of the Narwhal and Ship Fever

‘Doerr bears witness to history here – not the traditional history of big events or great people, but the small, anonymous corners from which the best stories can be told. Here is that rare and brave thing, a writer who doesn’t succumb to any of the easy temptations, but still manages to make a unique, powerful, and accessible music. Quite simply, this is the best collection of short stories that I’ve read in years.’

COLUM McCANN, author of Dancer

‘An impressive first collection…Doerr’s stories evoke the ecstatic feeling that comes from loving something or someone very much.’

TLS

‘Excellent stories…Doerr makes miraculous happenings seem natural because of his clean, classic style, an impressive achievement.’

Sunday Times

‘This assured literary debut has an almost ethereal quality about it: eerie and otherworldly in atmosphere, yet lucid, crisp and graceful in style. These short stories are linked by the overall themes of the complicated profundities of human emotion, the awe-inspiring beauty of nature and the numinous miracles of love…Doerr’s characters will hang around in your dreams long after you’ve finished the book.’

Venue

‘Doerr is fascinated by the way that the shape of things we can hold in our hands might be analogous to the shape of things we struggle harder to understand: love, loss, memory…When Doerr combines his talent for vivid observation with an understated look at some of the trials of being human he manages to move us far more often than not.’

Hampstead & Highgate Express

‘Loss, estrangement and distance are the collection’s keynotes. Doerr frames and executes these stories with seemingly effortless panache.’

Economist

‘The shell collector of the title is a blind man who roams the beaches of Kenya, feeling his way through the sand in search of smooth prizes. He’s just one of the enigmatic characters who populate the short stories in this strange, beautifully written collection.’

Sunday Tribune

‘Quite simply amazing. Not since Rick Bass’s The Watch has a first collection roamed so far in both language and landscape, presenting the natural and human-made worlds with equal beauty and awe.’

TOM FRANKLIN, author of Poachers

for Shauna

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

The Shell Collector

The Hunter’s Wife

So Many Chances

For a Long Time This Was Griselda’s Story

July Fourth

The Caretaker

A Tangle by the Rapid River

Mkondo

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

THE SHELL COLLECTOR

The shell collector was scrubbing limpets at his sink when he heard the water taxi come scraping over the reef. He cringed to hear it—its hull grinding the calices of finger corals and the tiny tubes of pipe organ corals, tearing the flower and fern shapes of soft corals, and damaging shells too: punching holes in olives and murexes and spiny whelks, in Hydatina physis and Turris babylonia. It was not the first time people tried to seek him out.

He heard their feet splash ashore and the taxi motor off, back to Lamu, and the light singsong pattern of their knock. Tumaini, his German shepherd, let out a low whine from where she was crouched under his sleeping cot. He dropped a limpet into the sink, wiped his hands and went, reluctantly, to greet them.

They were both named Jim, overweight reporters from a New York tabloid. Their handshakes were slick and hot. He poured them chai. They occupied a surprising amount of space in the kitchen. They said they were there to write about him: they would stay only two nights, pay him well. How did $10,000 American sound? He pulled a shell from his shirt pocket—a cerith—and rolled it in his fingers. They asked about his childhood: did he really shoot caribou as a boy? Didn’t he need good eyes for that?

He gave them truthful answers. It all held the air of whim, of unreality. These two big Jims could not actually be at his table, asking him these questions, complaining of the stench of dead shellfish. Finally they asked him about cone shells and the strength of cone venom, about how many visitors had come. They asked nothing about his son.

All night it was hot. Lightning marbled the sky beyond the reef. From his cot he heard siafu feasting on the big men and heard them claw themselves in their sleeping bags. Before dawn he told them to shake out their shoes for scorpions and when they did one tumbled out. It made tiny scraping sounds as it skittered under the refrigerator.

He took his collecting bucket and clipped Tumaini into her harness, and she led them down the path to the reef. The air smelled like lightning. The Jims huffed to keep up. They told him they were impressed he moved so quickly.

“Why?”

“Well,” they murmured, “you’re blind. This path ain’t easy. All these thorns.”

Far off, he heard the high, amplified voice of the muezzin in Lamu calling prayer. “It’s Ramadan,” he told the Jims. “The people don’t eat when the sun is above the horizon. They drink only chai until sundown. They will be eating now. Tonight we can go out if you like. They grill meat in the streets.”

By noon they had waded a kilometer out, onto the great curved spine of the reef, the lagoon slopping quietly behind them, a low sea breaking in front. The tide was coming up. Unharnessed now, Tumaini stood panting, half out of the water on a mushroom-shaped dais of rock. The shell collector was stooped, his fingers middling, quivering, whisking for shells in a sandy trench. He snatched up a broken spindle shell, ran a fingernail over its incised spirals. “Fusinus colus,” he said.

Automatically, as the next wave came, the shell collector raised his collecting bucket so it would not be swamped. As soon as the wave passed he plunged his arms back into sand, his fingers probing an alcove between anemones, pausing to identify a clump of brain coral, running after a snail as it burrowed away.

One of the Jims had a snorkeling mask and was using it to look underwater. “Lookit these blue fish,” he gasped. “Lookit that blue.”

The shell collector was thinking, just then, of the indifference of nematocysts. Even after death the tiny cells will discharge their poison—a single dried tentacle on the shore, severed eight days, stung a village boy last year and swelled his legs. A weeverfish bite bloated a man’s entire right side, blacked his eyes, turned him dark purple. A stone fish sting corroded the skin off the sole of the shell collector’s own heel, years ago, left the skin smooth and printless. How many urchin spikes, broken but still spurting venom, had he squeezed from Tumaini’s paw? What would happen to these Jims if a banded sea snake came slipping up between their fat legs? If a lion fish was dropped down their collars?

“Here is what you came to see,” he announced, and pulled the snail—a cone—from its collapsing tunnel. He spun it and balanced its flat end on two fingers. Even now its poisoned proboscis was nosing forward, searching him out. The Jims waded noisily over.

“This is a geography cone,” he said. “It eats fish.”

“That eats fish?” one of the Jims asked. “But my pinkie’s bigger.”

“This animal,” said the shell collector, dropping it into his bucket, “has twelve kinds of venom in its teeth. It could paralyze you and drown you right here.”

This all started when a malarial Seattle-born Buddhist named Nancy was stung by a cone shell in the shell collector’s kitchen. It crawled in from the ocean, slogging a hundred meters under coconut palms, through acacia scrub, bit her and made for the door.

Or maybe it started before Nancy, maybe it grew outward from the shell collector himself, the way a shell grows, spiraling upward from the inside, whorling around its inhabitant, all the while being worn down by the weathers of the sea.

The Jims were right: the shell collector did hunt caribou. Nine years old in Whitehorse, Canada, and his father would send the boy leaning out the bubble canopy of his helicopter in cutting sleet to cull sick caribou with a scoped carbine. But then there was choroideremia and degeneration of the retina; in a year his eyesight was tunneled, spattered with rainbow-colored halos. By twelve, when his father took him four thousand miles south, to Florida to see a specialist, his vision had dwindled into darkness.

The ophthalmologist knew the boy was blind as soon as he walked through the door, one hand clinging to his father’s belt, the other arm held straight, palm out, to stiff-arm obstacles. Rather than examine him—what was left to examine?—the doctor ushered him into his office, pulled off the boy’s shoes and walked him out the back door down a sandy lane onto a spit of beach. The boy had never seen sea and he struggled to absorb it: the blurs that were waves, the smears that were weeds strung over the tideline, the smudged yolk of sun. The doctor showed him a kelp bulb, let him break it in his hands and scrape its interior with his thumb. There were many such discoveries: a small horseshoe crab mounting a larger one in the wavebreak, a fistful of mussels clinging to the damp underside of rock. But it was wading ankle deep, when his toes came upon a small round shell, no longer than a segment of his thumb, that the boy truly was changed. His fingers dug the shell up, he felt the sleek egg of its body, the toothy gap of its aperture. It was the most elegant thing he’d ever held. “That’s a mouse cowry,” the doctor said. “A lovely find. It has brown spots, and darker stripes at its base, like tiger stripes. You can’t see it, can you?”

But he could. He’d never seen anything so clearly in his life. His fingers caressed the shell, flipped and rotated it. He had never felt anything so smooth—had never imagined something could possess such deep polish. He asked, nearly whispering: “Who made this?” The shell was still in his hand, a week later, when his father pried it out, complaining of the stink.

Overnight his world became shells, conchology, the phylum Mollusca. In Whitehorse, during the sunless winter, he learned Braille, mail-ordered shell books, turned up logs after thaws to root for wood snails. At sixteen, burning for the reefs he had discovered in books like The Wonders of Great Barrier, he left Whitehorse for good and crewed sailboats through the tropics: Sanibel Island, St. Lucia, the Batan Islands, Colombo, Bora Bora, Cairns, Mombassa, Moorea. All this blind. His skin went brown, his hair white. His fingers, his senses, his mind—all of him—obsessed over the geometry of exoskeletons, the sculpture of calcium, the evolutionary rationale for ramps, spines, beads, whorls, folds. He learned to identify a shell by flipping it up in his hand; the shell spun, his fingers assessed its form, classified it: Ancilla, Ficus, Terebra. He returned to Florida, earned a bachelor’s in biology, a Ph.D. in malacology. He circled the equator; got terribly lost in the streets of Fiji; got robbed in Guam and again in the Seychelles; discovered new species of bivalves, a new family of tusk shells, a new Nassarius, a new Fragum.

Four books, three Seeing Eye shepherds, and a son named Josh later, he retired early from his professorship and moved to a thatch-roofed kibanda just north of Lamu, Kenya, one hundred kilometers south of the equator in a small marine park in the remotest elbow of the Lamu Archipelago. He was fifty-eight years old. He had realized, finally, that he would only understand so much, that malacology only led him downward, to more questions. He had never comprehended the endless variations of design: Why this lattice ornament? Why these fluted scales, these lumpy nodes? Ignorance was, in the end, and in so many ways, a privilege: to find a shell, to feel it, to understand only on some unspeakable level why it bothered to be so lovely. What joy he found in that, what utter mystery.

Every six hours the tides plowed shelves of beauty onto the beaches of the world, and here he was, able to walk out into it, thrust his hands into it, spin a piece of it between his fingers. To gather up seashells—each one an amazement—to know their names, to drop them into a bucket: this was what filled his life, what overfilled it.

Some mornings, moving through the lagoon, Tumaini splashing comfortably ahead, he felt a nearly irresistible urge to bow down.

But then, two years ago, there was this twist in his life, this spiral that was at once inevitable and unpredictable, like the aperture in a horn shell. (Imagine running a thumb down one, tracing its helix, fingering its flat spiral ribs, encountering its sudden, twisting opening.) He was sixty-three, moving out across the shadeless beach behind his kibanda, poking a beached sea cucumber with his toe, when Tumaini yelped and skittered and dashed away, galloping downshore, her collar jangling. When the shell collector caught up, he caught up with Nancy, sunstroked, incoherent, wandering the beach in a khaki travel suit as if she had dropped from the clouds, fallen from a 747. He took her inside and laid her on his cot and poured warm chai down her throat. She shivered awfully; he radioed Dr. Kabiru, who boated in from Lamu.

“A fever has her,” Dr. Kabiru pronounced, and poured sea water over her chest, swamping her blouse and the shell collector’s floor. Eventually her fever fell, the doctor left, and she slept and did not wake for two days. To the shell collector’s surprise no one came looking for her—no one called; no water taxis came speeding into the lagoon ferrying frantic American search parties.

As soon as she recovered enough to talk she talked tirelessly, a torrent of personal problems, a flood of divulged privacies. She’d been coherent for a half hour when she explained she’d left a husband and kids. She’d been naked in her pool, floating on her back, when she realized that her life—two kids, a three-story Tudor, an Audi wagon—was not what she wanted. She’d left that day. At some point, traveling through Cairo, she ran across a neo-Buddhist who turned her onto words like inner peace and equilibrium. She was on her way to live with him in Tanzania when she contracted malaria. “But look!” she exclaimed, tossing up her hands. “I wound up here!” As if it were all settled.

The shell collector nursed and listened and made her toast. Every three days she faded into shivering delirium. He knelt by her and trickled seawater over her chest, as Dr. Kabiru had prescribed.

Most days she seemed fine, babbling her secrets. He fell for her, in his own unspoken way. In the lagoon she would call to him and he would swim to her, show her the even stroke he could muster with his sixty-three-year-old arms. In the kitchen he tried making her pancakes and she assured him, giggling, that they were delicious.

And then one midnight she climbed onto him. Before he was fully awake, they had made love. Afterward he heard her crying. Was sex something to cry about? “You miss your kids,” he said.

“No.” Her face was in the pillow and her words were muffled. “I don’t need them anymore. I just need balance. Equilibrium.”

“Maybe you miss your family. It’s only natural.”

She turned to him. “Natural? You don’t seem to miss your kid. I’ve seen those letters he sends. I don’t see you sending any back.”

“Well he’s thirty…” he said. “And I didn’t run off.”

“Didn’t run off? You’re three trillion miles from home! Some retirement. No fresh water, no friends. Bugs crawling in the bathtub.”

He didn’t know what to say: What did she want anyhow? He went out collecting.

Tumaini seemed grateful for it, to be in the sea, under the moon, perhaps just to be away from her master’s garrulous guest. He unclipped her harness; she nuzzled his calves as he waded. It was a lovely night, a cooling breeze flowing around their bodies, the warmer tidal current running against it, threading between their legs. Tumaini paddled to a rock perch, and he began to roam, stooped, his fingers probing the sand. A marlinspike, a crowned nassa, a broken murex, a lined bullia, small voyagers navigating the current-packed ridges of sand. He admired them, and put them back where he found them. Just before dawn he found two cone shells he couldn’t identify, three inches long and audacious, attempting to devour a damselfish they had paralyzed.

When he returned, hours later, the sun was warm on his head and shoulders and he came smiling into the kibanda to find Nancy catatonic on his cot. Her forehead was cold and damp. He rapped his knuckles on her sternum and she did not reflex. Her pulse measured at twenty, then eighteen. He radioed Dr. Kabiru, who motored his launch over the reef and knelt beside her and spoke in her ear. “Bizarre reaction to malaria,” the doctor mumbled. “Her heart hardly beats.”

The shell collector paced his kibanda, blundered into chairs and tables that had been unmoved for ten years. Finally he knelt on the kitchen floor, not praying so much as buckling. Tumaini, who was agitated and confused, mistook despair for playfulness, and rushed to him, knocking him over. Lying there, on the tile, Tumaini slobbering on his cheek, he felt the cone shell, the snail inching its way, blindly, purposefully, toward the door.

Under a microscope, the shell collector had been told, the teeth of certain cones look long and sharp, like tiny translucent bayonets, the razor-edged tusks of a miniature ice-devil. The proboscis slips out the siphonal canal, unrolling, the barbed teeth spring forward. In victims the bite causes a spreading insentience, a rising tide of paralysis. First your palm goes horribly cold, then your forearm, then your shoulder. The chill spreads to your chest. You can’t swallow, you can’t see. You burn. You freeze to death.

“There is nothing,” Dr. Kabiru said, eyeing the snail, “I can do for this. No antivenom, no fix. I can do nothing.” He wrapped Nancy in a blanket and sat by her in a canvas chair and ate a mango with his penknife. The shell collector boiled the cone shell in the chai pot and forked the snail out with a steel needle. He held the shell, fingered its warm pavilion, felt its mineral convolutions.

Ten hours of this vigil, this catatonia, a sunset and bats feeding and the bats gone full-bellied into their caves at dawn and then Nancy came to, suddenly, miraculously, bright-eyed.

“That,” she announced, sitting up in front of the dumbfounded doctor, “was the most incredible thing ever.” Like she had just finished viewing some hypnotic, twelve-hour cartoon. She claimed the sea had turned to ice and snow blew down around her and all of it—the sea, the snowflakes, the white frozen sky—pulsed. “Pulsed!” she shouted. “Sssshhh!” she yelled at the doctor, at the stunned shell collector. “It’s still pulsing! Whump! Whump!”

She was, she exclaimed, cured of malaria, cured of delirium; she was balanced. “Surely,” the shell collector said, “you’re not entirely recovered,” but even as he said this he wasn’t so sure. She smelled different, like melt-water, like slush, glaciers softening in spring. She spent the morning swimming in the lagoon, squealing and splashing. She ate a tin of peanut butter, practiced high leg kicks on the beach, cooked a feast, swept the kibanda, sang Neil Diamond songs in a high, scratchy voice. The doctor motored off, shaking his head; the shell collector sat on the porch and listened to the palms, the sea beyond them.

That night there was another surprise: she begged to be bitten with a cone again. She promised she’d fly directly home to be with her kids, she’d phone her husband in the morning and plead forgiveness, but first he had to sting her with one of those incredible shells one more time. She was on her knees. She pawed up his shorts. “Please,” she begged. She smelled so different.

He refused. Exhausted, dazed, he sent her away on a water taxi to Lamu.

The surprises weren’t over. The course of his life was diving into its reverse spiral by now, into that dark, whorling aperture. A week after Nancy’s recovery, Dr. Kabiru’s motor launch again came sputtering over the reef. And behind him were others; the shell collector heard the hulls of four or five dhows come over the coral, heard the splashes as people hopped out to drag the boats ashore. Soon his kibanda was crowded. They stepped on the whelks drying on the front step, trod over a pile of chitons by the bathroom. Tumaini retreated under the shell collector’s cot, put her muzzle on her paws.

Dr. Kabiru announced that a mwadhini, the mwadhini of Lamu’s oldest and largest mosque, was here to visit the shell collector, and with him were the mwadhini’s brothers, and his brothers-in-law. The shell collector shook the men’s hands as they greeted him, dhow-builders’ hands, fishermen’s hands.

The doctor explained that the mwadhini’s daughter was terribly ill; she was only eight years old and her already malignant malaria had become something altogether more malignant, something the doctor did not recognize. Her skin had gone mustard-seed yellow, she threw up several times a day, her hair fell out. For the past three days she had been delirious, wasted. She tore at her own skin. Her wrists had to be bound to the headboard. These men, the doctor said, wanted the shell collector to give her the same treatment he had given the American woman. He would be paid.

The shell collector felt them crowded into the room, these ocean Muslims in their rustling kanzus and squeaking flip-flops, each stinking of his work—gutted perch, fertilizer, hull-tar—each leaning in to hear his reply.

“This is ridiculous,” he said. “She will die. What happened to Nancy was some kind of fluke. It was not a treatment.”

“We have tried everything,” the doctor said.

“What you ask is impossible,” the shell collector repeated. “Worse than impossible. Insane.”

There was silence. Finally a voice directly before him spoke, a strident, resonant voice, a voice he heard five times a day as it swung out from loudspeakers over the rooftops of Lamu and summoned people to prayer. “The child’s mother,” the mwadhini began, “and I, and my brothers, and my brothers’ wives, and the whole island, we have prayed for this child. We have prayed for many months. It seems sometimes that we have always prayed for her. And then today the doctor tells us of this American who was cured of the same disease by a snail. Such a simple cure. Elegant, would you not say? A snail that accomplishes what laboratory capsules cannot. Allah, we reason, must be involved in something so elegant. So you see. These are signs all around us. We must not ignore them.”

The shell collector refused again. “She must be small, if she is only eight. Her body will not withstand the venom of a cone. Nancy could have died—she should have died. Your daughter will be killed.”

The mwadhini stepped closer, took the shell collector’s face in his hands. “Are these,” he intoned, “not strange and amazing coincidences? That this American was cured of her afflictions and that my child has similar afflictions? That you are here and I am here, that animals right now crawling in the sand outside your door harbor the cure?”

The shell collector paused. Finally he said, “Imagine a snake, a terribly venomous sea snake. The kind of venom that swells a body to bruising. It stops the heart. It causes screaming pain. You’re asking this snake to bite your daughter.”

“We’re sorry to hear this,” said a voice behind the mwadhini. “We’re very sorry to hear this.” The shell collector’s face was still in the mwadhini’s hands. After long moments of silence, he was pushed aside. He heard men, uncles probably, out at the washing sink, splashing around.

“You won’t find a cone out there,” he yelled. Tears rose to the corners of his dead sockets. How strange it felt to have his home overrun by unseen men.

The mwadhini’s voice continued: “My daughter is my only child. Without her my family will go empty. It will no longer be a family.”

His voice bore an astonishing faith, in the slow and beautiful way it trilled sentences, in the way it braided each syllable. The mwadhini was convinced, the shell collector realized, that a snail bite would heal his daughter.

The voice raveled on: “You hear my brothers in your backyard, clattering among your shells. They are desperate men. Their niece is dying. If they must, they will wade out onto the coral, as they have seen you do, and they will heave boulders and tear up corals and stab the sand with shovels until they find what they are looking for. Of course they too, when they find it, may be bitten. They may swell up and die. They will—how did you say it?—have screaming pain. They do not know how to capture such animals, how to hold them.”

His voice, the way he held the shell collector’s face. All this was a kind of hypnosis.

“You want this to happen?” the mwadhini continued. His voice hummed, sang, became a murmurous soprano. “You want my brothers to be bitten also?”

“I want only to be left alone.”

“Yes,” the mwadhini said, “left alone. A stay-at-home, a hermit, a mtawa. Whatever you want. But first, you will find one of these cone shells for my daughter, and you will sting her with it. Then you will be left alone.”

At low tide, accompanied by an entourage of the mwadhini’s brothers, the shell collector waded with Tumaini out onto the reef and began to upturn rocks and probe into the sand beneath to try to extract a cone. Each time his fingers flurried into loose sand, or into a crab-guarded socket in the coral, a volt of fear would speed down his arm and jangle his fingers. Conus tessulatus, Conus obscurus, Conus geographus, who knew what he would find. The waiting proboscis, the poisoned barbs of an expectant switchblade. You spend your life avoiding these things; you end up seeking them out.

He whispered to Tumaini, “We need a small one, the smallest we can,” and she seemed to understand, wading with her ribs against his knee, or paddling when it became too deep, but these men leaned in all around him, splashing in their wet kanzus, watching with their dark, redolent attention.

By noon he had one, a tiny tessellated cone he hoped couldn’t paralyze a housecat, and he dropped it in a mug with some seawater.

They ferried him to Lamu, to the mwadhini’s home, a surfside jumba with marble floors. They led him to the back, up a vermicular staircase, past a tinkling fountain, to the girl’s room. He found her hand, her wrist still lashed to the bedpost, and held it. It was small and damp and he could feel the thin fan of her bones through her skin. He poured the mug out into her palm and folded her fingers, one by one, around the snail. It seemed to pulse there, in the delicate vaulting of her hand, like the small dark heart at the center of a songbird. He was able to imagine, in acute detail, the snail’s translucent proboscis as it slipped free of the siphonal canal, the quills of its teeth probing her skin, the venom spilling into her.

“What,” he asked into the silence, “is her name?”