Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

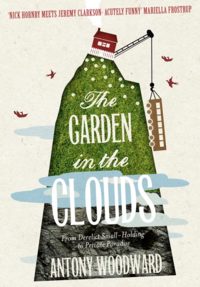

Kitabı oku: «The Garden in the Clouds: From Derelict Smallholding to Mountain Paradise», sayfa 2

2 Tair-Ffynnon

I usually skip topographical details in novels. The more elaborate the description of the locality, the more confused does my mental impression become. You know the sort of thing:—Jill stood looking out of the door of her cottage. To the North rose the vast peak of Snowdon. To the South swept the valley, dotted with fir trees. Beyond the main ridge of mountains a pleasant wooded country extended itself, but the nearer slopes were scarred and desolate. Miles below a thin ribbon of river wound towards the sea, which shone, like a distant shield, beyond the etc. etc. By the time I have read a little of this sort of thing I feel dizzy. Is Snowdon in front or behind? Are the woods to the right or to the left? The mind makes frenzied efforts to carry it all, without success. It would be very much better if the novelist said ‘Jill stood on the top of a hill, and looked down into the valley below.’ And left it at that.

BEVERLEY NICHOLS, Down the Garden Path, 1932

An obligatory requirement for any house in interesting country is a wall-map. Having made the satisfying discovery that Tair-Ffynnon was not only marked on the Black Mountains map, but mentioned by name—we were, literally, ‘on the map’—I wasted no time in pasting one up by the stairs. The map of the Black Mountains is a particularly pleasing one. The many contours make up the shape of a bony old hand, a left hand placed palm down by someone sitting opposite you. Four parallel ridges form the fingers, with the peaks of Mynydd Troed and Mynydd Llangorse constituting the joints of the thumb. At the joint between the second and third fingers is the Grwyne Fawr reservoir, up a long no through road. Between the third and fourth knuckles is the one through route, a mountain road that passes up the Llanthony Valley, past the abbey and Capel-y-Fin (‘the chapel at the end’) and up over the Gospel Pass (at 1,880 feet the highest road pass in Wales), before switchbacking down to Hay-on-Wye.

Hay, at the northern end, with its castle and bookshops and spring literary festival, is one of the three towns that skirt the Black Mountains. Crickhowell is to the south-west, beneath its flat-topped ‘Table Mountain’ (‘Crug Hywel’, from which the town takes its name). With its medieval bridge, antique shops and hint of gentility, Crickhowell is to the Black Mountains what Burford is to the Cotswolds. To the south-east, Abergavenny is the town with the least pretensions of the three, sitting beneath the great bulk of Blorenge (one of the few words in the English language to rhyme with ‘orange’) as Wengen sits beneath the Eiger. Central to our new universe was the Skirrid Mountain Garage, a name which conjured (to me, at least) wind-flayed and hail-battered petrol pumps huddled beneath a high pass, but which, in reality, was a homely establishment facing the mountain, selling everything the rural dweller could need, from chicken feed to homemade cakes.

Until some basic building work allowed us to move properly—installing central heating, replacing missing windows and slates, moving the bathroom upstairs—we were still only visiting Tair-Ffynnon at weekends, armed with drills and paint brushes. Our first night on the hill, after weeks of B&Bs down in the valley, felt as remote and exciting as bivouacking on Mount Everest, especially when we woke to find a hard, blue-skied frost had turned everything white and brought five Welsh Mountain ponies with romantically trailing manes and tails to drink at the bathtub where the spring emerged. The same day we spotted our first pair of red kites, easily distinguishable from the ubiquitous buzzards by their forked tails, elegant flight and mournful, whistled cries: pweee-ooo ee oo ee oo ee oo, pweee-ooo ee oo ee oo ee oo.

Between DIY efforts, we explored. no one who hasn’t moved to a new area can understand the excitement that almost every modest outing brings, be it merely trying out a pub or seeking a recommended shop, and the incidental discoveries the journey brings in the form of new views, a charming farm or enticing-looking walk for some future date. Much of our delight came just from being somewhere we’d chosen to be, as opposed to somewhere foisted upon us by our work or childhood. From growing up in Somerset I knew it was possible to live in a place without feeling the slightest connection with it, and the experience had left me hungry for knowledge of our new locality. Skirrid, Sugar Loaf and Blorenge, as the three triangulation points visible from most places, had to be climbed. The Black Hill and Golden Valley had to be inspected to see if they lived up to their names. Expeditions had to be mounted to walk Offa’s Dyke, and to drive the upland roads where Top Gear tested their supercars, to check out Cwmyoy church’s crooked tower and Kilpeck church’s saucy gargoyles of peeing women. And when we heard that a cult porn classic had been filmed in 1992 exclusively around a particular local farm, naturally we hurried off to see that too. The Revenge of Billy the Kid* (plot: farmer shags goat; monstrous half-goat-half-man progeny returns to kill his family) may not rank directly alongside Kilvert’s Diaries, Chatwin’s On the Black Hill, or Eric Gill’s sculptures (not that Gill’s extra-curricular activities were so far removed) but it still supplied local colour.

After the auction, when I’d shaken hands with the vendor’s solicitor, he’d said: ‘If you’ll be wanting a builder up there, I can recommend a tidy one. Very tidy.’ Any impartial recommendation of a local tradesman was plainly useful, given our newcomer status. And I could see that the notion of a tidy builder—the phrase, after all, was practically an oxymoron—was praiseworthy. But even if the one he was recommending was exceptionally orderly, even if he dusted every finished surface and ran the Hoover round before leaving, was this feature, in itself, sufficient justification for recommendation? Surely the foremost qualities for a builder must be workmanship, diligence, reliability, integrity, value for money, and so on, all before the undoubted bonus of tidy-mindedness?

Having, nevertheless, taken up his recommendation, over the succeeding weeks we heard mention of tidy jobs, tidy places, tidy machines, and it dawned that ‘tidy’, of course, didn’t really mean tidy at all, but was local vernacular for ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. As, in due course, we learnt that ‘ground’ was the term for ‘land’, cwtsh (pronounced ‘cutch’ as in ‘butch’) for cuddle, trow for ‘trough’, ‘by here’ for ‘here’ and so on, my favourite being the localised version of good-bye, the delightful ‘bye now’, as if parting were a mere trifling interruption, that resumption of contact was taken for granted. Phones, too, were generally answered with a joyful ‘’Alloooo’, as if you caught the recipient moments after his lottery win. The accent’s combination of Herefordshire and a hint of West Country, with a sing-song Welsh lilt, made communication easy on the ear, if periodically incomprehensible.

It also highlighted we were not just in a different place but in a different country, with a different language. ‘ARAF’ painted on roads at junctions meant ‘Slow’, while the word ‘HEDDLU’ appeared on the side of police cars. Signposts to bigger villages carried place names in both English and Welsh, however similar. The sign into our local village was large to accommodate (for absolute clarity) both ‘Llanfihangel Crucornau’ and ‘Llanvihangel Crucorney’. Cash machines offered Welsh instructions. Station and Post Office announcements were in Welsh as well as English. All official council, government or civil service documentation was bi-lingual, more than doubling its length. Names of smaller villages and individual properties tended to be in Welsh. In fact such a bewildering profusion of the same words kept cropping up again and again, of Pentwyns and Bettwses and Llanfihangels and Cwm-Thises and Nanty-Thats, that we bought a Welsh dictionary for the car. A new world emerged. In combination with words for ‘big’, ‘little’, ‘over’, ‘under’, ‘near’ or numbers, a poetic topography of landform sprang out.* Yet, despite this, and despite a general allegiance to Wales (especially evident during televised rugby finals), we soon discovered next to no one spoke or even understood Welsh.

The area seemed to be in the grip of a benign, easygoing, low-level identity crisis. Keen to learn a few basics, I spent an afternoon in the local reference library. The three classic guidebooks, A. G. Bradley’s In the March and Borderland of Wales (1905) and P. Thoresby Jones’s Welsh Border Country (1938) and H. J. Massingham’s The Southern Marches (1952), devoted pages simply trying to define where they were talking about. Everywhere there were signs of Welshness, or Englishness, or of a confusion between the two. Despite the unambiguous geophysical boundary of the ten-mile Hatterrall Ridge, the actual border with England ran only part of the way along its length, before descending to make various arbitrary and unpredictable kinks and turns, with the result that a short drive ‘round the mountain’ to Hereford or Hay crisscrossed the border repeatedly. So, not surprisingly, at least as many people seemed to be called Powell and Jones and Davies in neighbouring Herefordshire as in Monmouthshire. It was similarly interesting, if a little bewildering, to be given the option in every newsagent, however small, of nine local papers: the Abergavenny Chronicle, Monmouthshire Beacon, Abergavenny Free Press, Hereford Times, Brecon and Radnorshire Express, Western Mail, Western Free Press, Gwent Gazette and the South Wales Argus. For leisure moments, these were supplemented by the magazines Wye Valley Life, Usk Valley Life, Monmouthshire Life and Herefordshire Life, plus, for the macro view, Welsh Life. Whole sections of most newsagents were set aside for this remarkable array of verbiage. Even Abergavenny’s slogan—‘Markets, Mountains and More’—on signs hanging off lampposts and on its literature, suggested a certain doubt about exactly what it was the place stood for.

This uncertainty was echoed by the physical landscape. Upland or lowland? Sheep or cattle grazing? Hedge country or stone wall country? On the last question, most fields seemed to be a mixture, as if, halfway through walling, the waller had thought: ‘Sod this. Why don’t we just plant a hedge?’ Then, fifty years later when the hedges weren’t doing so well, another generation had said: ‘Hedges here? What were they thinking of? This should be a bloody wall.’ Even the birds seemed confused. At Tair-Ffynnon there were few trees but we had several fat green woodpeckers feeding off ants from the anthills, along with treecreepers and nuthatches. We had mountain birds like red kites and ravens, and moorland ones like red grouse and merlins. Yet we also had farmland birds like redstarts and fieldfares, water birds like yellow wagtails and herons, and garden birds: tits, chaffinches and blackbirds (though no songthrushes, strangely).

It was Border Country alright. Monmouthshire, a county in-between. But tidy, nevertheless.

My father and brother Jonny came to inspect the place. ‘D’you think my car will recover?’ said my father, parking his Fiesta after picking his way up the track. He looked well, but then he always did. Now in his eighties, he hardly seemed to have changed in the time I’d known him. Largely bald with white Professor Calculus-style hair, he’d looked old when he was young, but as his contemporaries aged, he’d just stayed the same. I bent down to kiss him, giving Jonny the usual curt nod. ‘Wonderful view. What a hideous house,’ said my father, fastidiously surveying the yard, taking in the scrap metal and the junk, as I helped him out of the car. ‘And what an appalling mess. What possessed you to buy this place, darling?’

I’d known my father wouldn’t like it. He loathed disorder, crudeness, ugliness. His relationship with the countryside was one of suspicion bordering on revulsion, and I guessed this counted as extreme countryside. I was impressed, frankly, given how bad the track was, he’d attempted it at all.

Although, technically, we’d all grown up in the country, in as much as our house was located in rural Somerset, ours wasn’t a rural existence. My father would vastly have preferred to live in the town. We were there entirely on my mother’s account, because she was obsessed with horses. Although dedicated to his garden, his interest was in abstract, strictly non-productive gardening. Most day-to-day aspects of rural living my father cordially detested. The getting stuck behind tractors and milk lorries. The smell of muck-spreading. The filth and slime with which the lanes steadily filled from December to March. It was a point almost of pride that he possessed not a solitary item of the default green country wear sold by shops with ‘country’ in their name. He was repelled by traditional rural activities such as hunting, shooting and fishing and would not have dreamt of attending an event such as the Badminton Horse Trials, had the latter not been forced upon him by my mother. Visiting churches, distinguished gardens and occasional walks up Crook’s Peak were the extent of his rural ambitions. We kept no animals, other than horses, and grew no fruit or vegetables. He wished for no contact with country people and did not enjoy having it foisted upon him (such as when he answered the door to find Ken, the farmer at the top of our lane, following one of the periodic shoots through the adjacent wood, bearing the unwelcome gift of a brace of pheasants). He made no secret of the fact that he was in the country on sufferance and would have preferred to occupy a terraced house in Bristol or Bath. Maybe it was from him that I acquired the sense of rural root-lessness that had driven me up a Welsh mountain.*

Although, technically, we’d all grown up in the country, in as much as our house was located in rural Somerset, ours wasn’t a rural existence. My father would vastly have preferred to live in the town. We were there entirely on my mother’s account, because she was obsessed with horses. Although dedicated to his garden, his interest was in abstract, strictly non-productive gardening. Most day-to-day aspects of rural living my father cordially detested. The getting stuck behind tractors and milk lorries. The smell of muck-spreading. The filth and slime with which the lanes steadily filled from December to March. It was a point almost of pride that he possessed not a solitary item of the default green country wear sold by shops with ‘country’ in their name. He was repelled by traditional rural activities such as hunting, shooting and fishing and would not have dreamt of attending an event such as the Badminton Horse Trials, had the latter not been forced upon him by my mother. Visiting churches, distinguished gardens and occasional walks up Crook’s Peak were the extent of his rural ambitions. We kept no animals, other than horses, and grew no fruit or vegetables. He wished for no contact with country people and did not enjoy having it foisted upon him (such as when he answered the door to find Ken, the farmer at the top of our lane, following one of the periodic shoots through the adjacent wood, bearing the unwelcome gift of a brace of pheasants). He made no secret of the fact that he was in the country on sufferance and would have preferred to occupy a terraced house in Bristol or Bath. Maybe it was from him that I acquired the sense of rural root-lessness that had driven me up a Welsh mountain.*

Jonny, on the other hand, was in heaven, as he methodically inspected every inch of the place, shed by shed, rusty wreck by rusty wreck. For fifteen years, Jonny’s day job had been as a Formula One motor-racing mechanic, at one time ending up as head of Ayrton Senna’s car—thus maintaining the Woodward tradition of having a job sufficiently specialised to be utterly meaningless to other members of the family. He was so shy, with us at least, he’d never, under any circumstances, contemplate leaving answerphone messages. Yet his spiky handwriting, indenting at least three sheets of paper beneath the one he was writing on, hinted at his determination once he’d set his mind on something. In recent years we’d bonded, bizarrely, over an affection for old farm machinery; the key difference between us being that he was a mechanical genius. Machines in his hands sprang back to life, as plants did in my mother’s, and as they died in my own.

‘Pick-up cylinder off an International B74 baler…radiator off a David Brown…top link arm…link box flap…hitch and footplates off a Super Major. Did you know your hay trailer’s the converted chassis of a Bedford Army Four-tonner?’

I could tell Jonny was as approving as it was possible for him to be.

‘I just do,’ said Jonny.

We went into the house for lunch. ‘What’s going there?’ asked Jonny, indicating the empty space left for the Aga.

‘An Aga.’

‘An Aga? How awful,’ said my father.

‘Oh, I don’t know. I rather like an Aga,’ said my brother. ‘What colour are you getting?’

‘Cream.’

‘Thank goodness for that.’

After lunch, Jonny returned to his inspection outside, exactly where he’d left off.

‘This hay rake’s been converted. Look, you can see where it used to be horse-drawn and they’ve welded a tractor hitch on. See, just there. Bamford’s side delivery rake…mmm, nice.’

‘What’s this called?’ We were standing next to a particularly eccentric-looking appliance which consisted of four huge metal wheels in an offset row, each spoked with sprung metal tines. From seeing it in the fields as a child, I knew it had been used for turning hay.

‘A Vicon Lily Acrobat.’ He enunciated the syllables slowly, ironically. We all smiled.

‘How do you know this stuff?’ said my father.

‘You’ve got three Ferguson ploughs, so whoever was here before you obviously had a Fergie. And a lot of this other kit’s for a Fergie too: the potato ridger, the spring tine cultivator. You can see it all used to be painted grey. Hmm,’ said Jonny, surveying it all. ‘Looks as if you’d better get yourself a tractor.’

Gradually, we began to meet our neighbours. Key amongst them was Ness, darkly beautiful, gypsy-like, striding the hill with a long-legged gait and her sheepdog Molly. She lived in a cottage behind a hedge on the lane and talked with a force and speed I have yet to encounter in another human being, as if life were too short to leave gaps between words. She was also, it soon emerged, a kind of self-appointed guardian of our corner of the National Park, waging a lone battle against what she regarded—aptly, in many people’s view—as mediocrity, idleness, bad taste, stupidity or the general failure of officialdom to discharge its duties adequately. Gratuitous street-lighting, crass development, over-signage—all fell within her remit as unofficial custodian. Early on I’d had the privilege of hearing her in action when I’d dropped in for something. Some ominous big ‘C’s had recently appeared in yellow paint on the trunks and branches of various trees on the lane up the hill, including one on the bole of a mighty, spreading oak. I found her pacing the room with a phone hooked under her chin. ‘So,arewequiteclearonthisMr.—?Ifanything—anything—happenstothattreefollowingthisconversation…IhaveyournameheresoIknowexactlywhotocomebackto.’

It was clear from her tone that her blood was up, that she’d been fobbed off by one jobsworth too many claiming he or she didn’t know what the markings meant, or that they were there in the name of health and safety. I watched agog as, with hurricane-force indefatigability, she worked her way up the hierarchy of plainly shell-shocked and unprepared officials until, when she decided she’d got far enough, she delivered her pièce de résistance: ‘Isthatclear?ForyourinformationIhavebeentaperecordingthisconversation,so,asIsay,Iwillbeholdingyoupersonallyresponsible.Thankyouverymuch.’ She put the phone down. ‘That should stir them up a bit,’ she said cheerfully, lighting a Silk Cut from a lighter marked ‘BUY YOUR OWN FUCKING LIGHTER’. ‘Now,canIofferyouacupofcoffeeord’youwantsomethingstronger?Gladyou’vecalledinbecauseI’vebeenmeaningtoaskyou…’

I need hardly add that the sentenced oak still stands, wearing its yellow death warrant like a badge of honour, a daily reminder that battles with mindless bureaucracy can be won.

Ness became a vital source of information from the start, issuing us with contact sheets of trusted local artisans, sources and suppliers, each accompanied by comprehensive briefing notes. Another was Les the Post. We enjoyed what must be one of the best-value mail services in the British Isles, with Les frequently negotiating two gates and a mile of rough track simply to deliver a flyer promising ‘Anglia Double Glazing now in your area’. He was regularly to be seen chivvying stray sheep back into their fields (being familiar with every local farmer’s markings) where we would just push uncertainly by, often herding them ever further from home. Start a conversation with Les, however, and, as he switched his engine off, you knew it was unlikely to last less than twenty minutes.

In February, we encountered our most exotic and colourful visitors to the hill. We’d had intimations of their presence, in the form of folded five pound notes wedged into cracks of the porch, or neat piles of coins left by the door, which we’d discover on Saturday mornings when we emerged, blinking, into the daylight. On this occasion, a car with long overhanging bundles on its roof-rack came racing up the track. It swept into the yard, and, without slowing, splashed through the muddy gateway to the field. Two figures leapt out and started untying the long bundles. After that, cars started arriving in a more or less steady stream. The wind was in the east. The hang-gliders and paragliders had arrived.

We’d already heard a lot about them. Within moments of getting Tair-Ffynnon at the auction, a man had introduced himself, congratulated us on our success, and explained he’d been the under-bidder, representing a consortium of hang and paraglider flyers. Were we aware, he said, that Tair-Ffynnon was one of the finest paragliding sites in the country? Apparently the Hatterrall Ridge was the first significant geological barrier to east-flowing air after the Urals on the far side of the Russian steppes two and a half thousand miles away. The previous owner had allowed, even encouraged, parking in her field: would we consider doing the same? I mumbled something about being sure we could work something out, only to discover I’d entered a minefield. The site was popular because the combination of the track and parking meant pilots could drive their heavy gear all the way to the take-off point, something few sites allowed. But permitting parking encouraged greater use of the site, sending Ness, for one, crazy from cars driving up and down past her house all day. We decided the best course for the time being was to do nothing.

There’s no doubt they were a dramatic spectacle in the late winter haze. The brightly coloured canopies of the paragliders stood out against the bracken and lichen-covered stone walls, and across the hill drifted the murmur of voices punctuated by the crackles and soft wumphs of air pockets inflating and deflating. We counted thirty in the air simultaneously that day. They brought a note of glamour and contemporaneity to the ancient hillside.

By the third week of February, the Aga still wasn’t installed. We’d ordered one secondhand and it was supposed to have been delivered and fitted by Christmas. After the delivery driver had failed to find Tair-Ffynnon on his first attempt, then declared the track too rough on his second, his third attempt coincided with a hard frost, converting the wet lane into an impassable sheet of ice. A fourth attempt was finally successful, but unfortunately by this time we’d missed our slot with the fitter. The disembowelled cooker was heaped in the lean-to pending his return from his January break. When he finally arrived, fresh and recuperated, he informed us the parts were from Agas of different dates and incompatible. As we’d torn out the existing Rayburn to make way for the Aga, the house was distinctly chilly and unwelcoming without either, so after that Vez declared we should not return to Tair-Ffynnon until the correct Aga parts were ready for assembly.

Then the forecast promised snow in the south of England. During weekdays away from Tair-Ffynnon a curious imaginative process had started taking place. The less we were there, the more romantically unreal the place began to seem. Stuck in London, enduring yet another mild, drearily overcast day, what I wanted to know was: what was it like on the hill, in the high, clear, cold air there? I had no difficulty imagining that a place less than two hundred miles to the west of the capital and a thousand-odd feet higher could be experiencing an entirely different climate. I was convinced a frost in London must mean feet of snow on the hill. Indeed, it would have been but a step for me to believe woolly mammoths bestrode the ridge. I got sidetracked for almost a morning researching what kind of generator would be most suitable for the inevitable power cuts and how much snow chains would be for the car. So when genuine snow was promised—well, that could not be missed.

Thus it was against Vez’s better judgement that we descended off the elevated section of the Westway out of London that Friday afternoon, the car’s temperature gauge hovering at a disappointing +1°C. (I had become a compulsive watcher of the car’s temperature gauge, which routinely indicated a two-, three-, even four-degree difference between the bottom of the hill up to Tair-Ffynnon and the top.) By Reading, however, the digital display showed 0°C and big flakes started coming at us out of the night. Larger and larger, they made a soft, unfamiliar pfffffff…pfffffff…pfffffff…pfffffff…as they settled on the windscreen. The temperature started to drop promisingly…-1°C, -1.5°C, -2°C. ‘This is mad. We’ll never get up the hill. We should go back,’ said Vez.

‘Don’t be silly. What’s the point of having the place? Of course we’ll get up the hill. And if we can’t, I’ll get the Land Rover.’ The Land Rover now lived proudly in one of the sheds at Tair-Ffynnon.

‘We’ve got a four-month-old baby in the car and no supplies.’

‘We’ll be fine.’

By the time we turned off the main road, the countryside was white and so was the tarmac. At the bottom of the hill the temperature gauge showed a satisfying -4°C. As we turned up the unsigned lane it was hard to tell how deep the snow was, but there was enough on the ground to soften the edges between the road and the hedgerow banks. The lane led directly through the yard of a farm and we were about to join the road out the other side when the front wheels began to spin. We lost traction. I reversed back to try and gain momentum, but the wheels spun again. I tried a longer run-up, reversing all the way back to the turning. I could get no further. We were, indubitably, stuck.

Strapping on a backpack, and glowing with manly virtue, I crunched and squeaked my way up the hill through pristine powder snow. The clouds had cleared by this time, revealing a moonlit snowscape beneath an absurdly starry sky. Unfortunately, having reached the Land Rover, I found I had forgotten the keys, necessitating a slightly less satisfying trudge back down the hill to fetch Vez and Maya on foot. At length, however, we were installed in the house.

Next day I got the Land Rover out of its shed, but by then more snow had fallen and it was too deep for us to go anywhere. There wasn’t much to do except pass most of the weekend huddled in bed to keep warm. ‘I hope it was worth it,’ said Vez, a little uncharitably on Sunday, as we crouched over our fourth meal of canned soup, cooked on the old electric cooker, facing the space where the Aga was supposed to be. Eventually we trudged back down the hill to the car and returned to London.

The Aga in which we’d planned to cook our Christmas turkey was eventually installed and working in time for Easter and the spring.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.