Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Armenophobia in Azerbaijan», sayfa 5

4. Ban on Armenian names

The custom of banning names is quite common in the world. Such bans have their rationale based on the interests of children, protection of the current ideology and set of values.

Thus, many countries have a strict state-regulated procedure for assigning names to the children by their parents who often chase the tendencies in vogue and choose quite exotic names, such as: Kanalizatsia, Tractor, Lucifer, Number 16 Bus Shelter, Biological Object Human descendant of the Voronins and Frolovs born on June 26, 2002, digital names, etc. For instance, China has long maintained a ban on naming children after representatives of the imperial family, particularly those of the dynasty in power; such names had to be changed. Some countries taboo names related to religious views; for instance, certain countries place a ban on such names as Lucifer and alike.

The restrictions and bans in Azerbaijan have to deal with the ethnic origin of the name.

In 2011, the Academy of Sciences and the Government of Azerbaijan approved a principle of the traffic light, according to which the state authorities themselves determine the list of trustworthy and prohibited names for children that Azerbaijan parents can choose from.

The Director of the Institute of Information Technologies of ANAS, Rasim Aliguliyev, has noted that based on the principle of the traffic light, the names which “correspond to the national, cultural and ideological values of Azerbaijan” will be included in the green list and can be assigned without any restrictions.

The second category will be comprised of names included in the yellow list. These names are neither desirable nor recommended; they cause derision and sound inappropriate in other languages.

Names of the third category will be included in the red list; assigning of these names will not be allowed. “Such names include the names of persons who have perpetrated aggression against the people of Azerbaijan, names whose meaning is offensive in the Azerbaijani language”.141

Armenian names were included in the red list of prohibited names. According to Rasim Aliguliyev, “it is unacceptable in Azerbaijan to name your baby Andranik”.142 That comes to say that if a Lezgin wants to name his son Arsen – a name very popular both among Armenians and Lezgins, or if a Talysh wants to name his son Armin – a name quite popular among both Armenian and Talysh people, he will have to apply to the commission for a special authorization.

Russian names, too, came under attack. According to Sayali Sagidova, the chairman of the Commission, “not every Azerbaijani family would marry their daughter off to somebody named Dmitry”.143 A ban will be also placed on such names as Maria, Ekaterina, Alya and other Russian names.

Also, a special commission of the National Academy of Sciences approved a bill imposing changes in the last names used in Azerbaijan where endings with – ov and – ev would be substituted by their Turkicized variants of – lu, – li, -beyli, etc.

Nizami Jafarov, Chairman of the Azerbaijani Parliamentary Committee on Cultural Issues, when asked how this new law would affect the national minorities of Azerbaijan, such as Lezgins, Talysh, Avars, Tats and representatives of other ethnic groups gave this answer: “The question on the agenda is as follows; every person who considers himself/herself Azerbaijani – and most of the ethnic minorities of Azerbaijan have merged with the Azerbaijani people and consider themselves Azerbaijani – will have to change his/her last n a me”.144

This lays a very interesting groundwork not only for fast-tracking the assimilation processes of the indigenous population of Azerbaijan, but is in direct contravention of the country’s declared set of values, such as tolerance and cultural diversity, the commitment to which the myth of 30,000 Armenians living on the territory of Azerbaijan purports to illustrate.

It appears that the ethnic Armenians who live today on the territory of Azerbaijan are automatically divested of any chance to keep and develop their cultural traditions by naming their children Andranik145, Armen, Hrayr or alike.

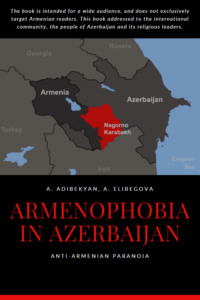

Azerbaijan’s appetite for integration of the Armenian-populated territory of Nagorno-Karabakh inevitably leads to a series of conclusions, such as:

(a) Armenians of Karabakh and citizens of Azerbaijan will be prohibited from using their own ethnic names entered into the red list. This will violate their rights, or they will be outlawed;

(b) Azerbaijan is working out an option of returning Karabakh without Armenians populating its territory which means that they will have to face a forceful assimilation or banishment, which is in contradiction of the promised concept of the widest autonomy possible;

(c) The Azerbaijani power elite have ceased to view Karabakh as an integral part of their country on a subconscious level; therefore, in adopting certain laws, they completely disregard the interests of the population which itself has long lost the feeling of affiliation with Azerbaijan.

It is noteworthy that the Azerbaijanis themselves, despite their claims of individual ethnic identity, lack traditional Azerbaijani ethnic names. These names can be exclusively traced back to: Arabic roots, adapted through Islam (Seid, Seyran, Ali, Vugar, Rasim, Zia, Ilham), Iranian roots (Panah, Nariman, Bahram, Rovshan, Siyavush, Azar) and Armenian roots (Mayis). The Iranian-speaking Talysh people bear ethnic names from pre-Islamic period, such as: Zardusht146, Kadus147, Zabil, Kekul, Shali, Chessaret, Ferin, Revane, and Sherebanu. The practice of using names common for all Turkic people from Altai to Turkey, such as Ogtay, Elnur, Atakhan, Elshan, Altay has been introduced but a few decades ago which is at odds with the concept of genuine ethnic names.

5. Entry ban to Azerbaijan

An extraordinary manifestation of armenophobia and incitement to hatred take form of banning the entry for ethnic Armenians who are not Armenian residents or nationals.

The practice of banning entry is quite common worldwide. Thus, certain conflicting, warring or ideologically opposed countries impose similar bans (Israel and Muslim countries), significantly complicate the entry visa issuing procedure (India and Pakistan) and sometimes go as far as imposing fines or arresting the person concerned (Georgia and Abkhazia or Southern Ossetia).

Azerbaijan, in its turn, has mimicked the practices of other countries amalgamating their methods into an arrangement that above all is in contradiction with its commitment to the principles of tolerance avowed domestically and internationally. The emotional character of this decision along with its chaotic application and insufficient elaboration made the enforcement of this mechanism quite perplexing. This latter circumstance frequently leads to scandals and some singular incidents.

First, the self-ascribed commitment to the principle of tolerance prevents Azerbaijan from placing a legislative ban officially proscribing the entry of ethnic Armenians into the country. Second, the absence of an unambiguous regulatory document such as a law or a sublegislative act lends absurdity to the actions of the Azerbaijani officials. Third, the citizens of Azerbaijan themselves and the officers of international agencies have hard time pinpointing where the denied entry, removal, detainment or deportation of a specific person is legitimate and where it is not so.

Two football players from the Russian club Torpedo of Armavir were deported from Azerbaijan immediately upon their arrival at the airport of the city Ganja in July 2011 on the account of their Armenian origin. Mehman Allahverdiev, the head coach of the Azerbaijani football club Kapaz, had invited Armenian football players for an audition, however, it was reported that he had had no prior knowledge of the Armenian origin of the Russian players. Their arrival drew a great uproar at the airport of Ganja. The officers of the State Border Service returned the Armenian football players who held Russian passports on the same plane in which they had arrived.148

In 2010, the Armenian delegation was unable to board a plane from Moscow to Baku to attend the 64th General Assembly of the European Broadcasting Union due to the wrongful acts of the Azerbaijan’s representative office of Aeroflot Air Company.149

The representatives of the Armenian delegation were about to board the plane when the representative of the Azerbaijani side asked the passengers if there were any Armenians among them. Hearing an affirmative answer, she asked Armenians to hand over their boarding passes and step aside. After all passengers including numerous participants of the EBU General Assembly boarded the plane, the boarding passes of the Armenian representatives were shredded, and they were told that passenger seats in the plane were complete which by definition could not make any sense as the tickets of the Armenian delegation members were in the business class. Moreover, the boarding pass indicates a seat assigned to a specific passenger; therefore, it is virtually impossible to register two passengers for the same seat.

In November 2011, the officers of the passport control service at the airport of Baku denied entry to the interim head of the Public Relations Department of the company Beeline Kazakhstan, Mr. Bayram Azizov on the ground that he had previously been to Yerevan on a working visit;150 incidentally, he was a citizen of Kazakhstan and an ethnic Azerbaijani. The aggrieved person had to spend 48 hours in the transit zone of the Baku airport before his deportation to the country of origin. It is worth mentioning that Mr. Bayram Azizov tried to seek assistance from the head of the Azerbaijani state by posting a message on the Twitter account of the president Ilham Aliyev: “Good day! Please, help me! I’m a citizen of Kazakhstan. It’s almost 48 hours since I have been in the transit zone of the airport of Baku. Border guards have seized my passport, and I don’t understand the reason of my detention. I have to sleep on the floor and feed myself on instant noodle! I’m running out of money! The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan has been made aware of the situation”. Unfathomably, both postings somehow disappeared from Aliyev’s Twitter account.

In reply to a remark from a journalist of Vesti.az news agency to the effect that a person who had visited Armenia would face difficulties in entering Azerbaijan, the aggrieved person said that he had traveled into Georgia approximately a year prior to that and could easily cross Georgian-Armenian border despite his Azerbaijani ethnicity indicated in his passport.151

Reasons for denying entry:

1. Visit to Nagorno-Karabakh Republic through the territory of Armenia;152

2. Visit to Armenia;

3. Armenian origin, existence of Armenian relatives or friends, expressing feelings of sympathy towards Armenia or Armenian people;

4. Incapacity to secure the safety of Armenians visiting Azerbaijan;

5. Suspicions of a terrorist threat;

6. Existence of a law to that effect;

7. Names that arouse suspicions because they sound Armenian, or an alleged relation to Armenians;

8. Persons whose relatives or acquaintances have committed insulting or outrageous acts from the Azerbaijani perspective (a concert by a popular singer Philip Kirkorov was canceled in Baku because at the time his father was helping an Armenian disabled boy153).

Sufian Zhemukhov: The secret of my name was revealed during my visit to an international workshop in Baku, to where I flew from Istanbul. At customs, a good-looking Azerbaijani lady checked my passport. <…> In fact, that lady called an officer of Azerbaijani special services and handed him my passport. The officer joined his colleague at the other end of the hall where they long conferred together and even made some telephone calls. After that, they beckoned me and asked: “This name of yours, what is it?” <…> Then they asked me bluntly: “So, this means it’s not an Armenian name?” Then, it all dawned on me. These cloaked Turkish officers and their simple-minded Azerbaijani colleagues took me for a crafty Armenian trying to sneak into their country! <…> “No, no, Sufian is not an Armenian name”, reassured them I. And I breathed a mixed sigh of relief and anguish. It seemed that the problem was not my name but their anti-Armenian complexes. <…> Later, An American told me that he, too, had had problems at the Azerbaijani customs because his passport had an Armenian visa. Although as it is, it appears that they should never stop bowing, if they take an American passport into their hands. This put my mind in rest about my red-skin passport. Of course, I have heard that Armenians and Azerbaijanis dislike each other, but I never knew that it was that serious.154

Zurab Dvali: The first hassles started when we measured the height of the wall once and then began to build the same scene for the shooting.”But you have already measured the wall, why are you doing it all over again?” asked a cheerless party official sporting a golden signature of H. Aliyev pinned on his lapel. <…> “Oh, no,” groaned the vigilant party leader Abbasov. “You are deceiving us; you have come here to shoot something else!” And precisely at that moment he noticed a book in Georgian that a member of our expedition, geographer Kakhi Jelia was holding in his hands. “What is this?” he asked. “A book on ancient Georgian architecture”. <…> The book published back in 1979 and authored by a famous scientist Ilia Adamia was a bombshell for Abbasov. All of a sudden, he started calling someone and went off into a loud discussion accompanied by an intensive body language. Then, seeing our bewilderment, he finally uttered: “The Armenian finger!” We all exchanged bewildered glances without understanding the meaning of it. Only later did we find out that the party bigwig somehow thought that the last name ‘Adamia’ was an Armenian one. Another ten plain-clothes officers rushed to his ear-piercing scream. We were surrounded, but refused to hand over the book. But our work had to be done, and amid this disapproving buzz of the local populace, we started the shooting. Our every step, our every move around the village was supervised from three cars that accompanied us.

<…> We had no other choice but to give everything up and head for the border. As we were leaving Balakan, we were intercepted by a state security car cutting in front of us and were escorted to the Office of Islam Rzayev, the Chairman of the Executive Committee of Balakan region. The indefatigable party leader kept pointing his finger at our book and finally asked: “Who is Adamia?” “A Georgian scientist”, we replied. He looked at Abbasov. “Georgian? Not Armenian?” asked Rzayev again with a dubious voice. “ADAMIA is a Mingrelian last name”, we all admitted in unison.155

The first point is more or less clear; yet, in the remaining cases, a question stands: is it about the law or security?

Thus, Diana Markosyan, a photo correspondent of Bloomberg agency, a national of the United States and Russian Federation, was deported from Baku to Istanbul on the ground of her Armenian origin in June 2011.156 The press service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan confirmed the deportation of the Bloomberg photo correspondent because of her Armenian descent:

“Markosyan’s stay in Azerbaijan will raise issues related to securing her safety because of her Armenian origin”. It is hard to guess why an accredited journalist, a national of the United States and the Russian Federation may face the need to ensure her protection and security on the territory of a civilized and tolerant state. However, Ali Hasanov, the Head of the Department of Public and Political Issues of the Administration of the President of Azerbaijan, refers to violating a law, which does not exist: “This media company had sufficient other options and they could have sent another photo correspondent. Yet, insisting on the arrival of this specific correspondent is an affront to the laws of the country and is insulting to us. We cannot put up with this”.157

After the scandal with the Russian citizen Sergey Gyurjian158 the Azerbaijani newspaper Yeni Musavat made an attempt to figure out whether the entry ban for Armenian citizens and nationals of other countries with Armenian lineage was official, or the arrangement was enforced informally.159

In October 2011, the representatives of Azerbaijani airlines (AZAL) at Domodedovo Airport prevented the representative of AVTOVAZ OJSC, Sergey Gyurjian, a Russian national, and his colleague Demitri Schuhmacher, an Israeli national and director of LADA International Limited company, from boarding the plane from Moscow to Baku where they went as a part of the delegation to strike a deal for shipment of LADA cars to Azerbaijan.160 An officer of the airline company who handled the registration of boarding documents asked a question about his ethnicity: “What is your ethnicity? Armenian?” To that, Gyurjian replied that he was a citizen of the Russian Federation, and his ethnicity had no bearing on the flight registration. However, Elgar Aliyev, the representative of AZAL Company, refused to proceed with the registration referring to an instruction from his management: “Not to register passengers with Armenian names”.161

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Azerbaijan skirted around a blunt question from the newspapers, and the head of the AZAL press service, Mehriban Safarli stated that their company “only dealt with passenger transportation and not their citizenship”. In her turn, Svetlana Rodionova, the representative of the Domodedovo Airport, stated that “the management of the airport prohibits the registration of Russian citizens of Armenian origin for flights to Baku”.

Unlike the management of AZAL, the head of the press service of the Azerbaijani Railways, Nadir Azmamedov stated that “the entry of Armenian citizens and ethnic Armenians who are nationals of other countries is officially prohibited”.

In relation to the notorious incident with Sergey Gyurjian, a representative of the airline company, Magerram Safarli stated: “It is known that 20 percent of Azerbaijan’s territories162 are occupied by Armenia. Therefore, a trip to Azerbaijan is considered undesirable for ethnic Armenians. For this reason, they can visit the country only as part of international events”, added Safarli.

Nevertheless, international events, too, are far from hassle-free. Thus, the Director of the Regional Studies Center Richard Giragosian was denied an Azerbaijani entry visa in March 2012 for participation in an international conference in Baku on the ground that the nomination of an Armenian expert was “unacceptable”.163 The same lot was reserved for a citizen of Turkey164 who had come to Baku as part of a Turkish delegation and a citizen of Latvia165 who had arrived to Baku as part of the delegation of the Latvian President.

<…> a few days ago, a Turkish singer Sertab Erener arrived in Baku. A musician named Burak Bedikyan, who came with the delegation of the Turkish singer and was a Turkish national of Armenian origin, was denied entry to Azerbaijan and had to return to where he came from. Upon his return to Turkey, Bedikyan made up his mind to give the local press a detailed tearjerker account of his stay at the airport of Baku. He insists that his denied entry to Azerbaijan related to his Armenian roots. Incidentally, this is not the first case when citizens of different countries who are ethnic Armenians are unable to gain entry into our country. On every such occasion, however, it is emphasized in Baku that they see no reason to give any clarification whatsoever as “authorizing or denying entry” is the right of every sovereign state.

<…> Another such incident happened during the visit of the Latvian President to Azerbaijan. Similarly, this time the Latvian delegation included an Armenian citizen of Latvia. “Despite the fact that he had arrived with the Latvian President, he was not allowed entry to our country and had to turn back.

In his commentary on the incident related to Mr. Bedikyan, who was a citizen of the “fraternal Turkey”, a department head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, T. Tagizadeh clarified: “He can even be a citizen of Vatican! Only we can decide who gets the visa and who doesn’t”.166

The absence of a regulated line of conduct can lead to the fact that entry into the country may be barred at three different levels:

• By the attending staff level of airports, airlines, railways or hotels. They may claim to do so at the behest of their superiors.

• By the staff of consular services, embassies and visa departments of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan;

• By the staff of the border guard service.

Forms of denying entry:

• Straightforward communication;

• Procrastination in issuing an entry visa;

• Issuing an entry visa and canceling it upon arrival in Azerbaijan;

• Entering the person’s name into blacklists before arrival or after departure.

A few years ago, the practice of blacklisting was introduced in Azerbaijan. This practice is quite common worldwide and concerns, as a rule, terrorists, internationally wanted criminals, drug lords, persons who have repeatedly violated visa procedures and recently has come to include corrupted public officials (Magnitsky List). This practice involves procedures, parameters, techniques and legislative instruments that have long been elaborated and are perfectly intelligible. Azerbaijan, however, has such a list, but it lacks a principle for entering and removing names.

In the beginning, such blacklist targeted persons who had ever visited Nagorno-Karabakh. Further, such lists were extended to include persons of Armenian lineage (Svetlana Loboda,167 Avraam Russo).

The impulsive and chaotic practice of blacklisting signals a lack of consistency, where people in identical situations may be penalized selectively.

On certain occasions, the press service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan issues threats to “investigate” and “keep in focus” numerous visits of international delegations to Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. Frequently, the results of these investigations by the Azerbaijani foreign office never surface, thereby making the selection criteria for blacklisting a specific political figure or journalist completely unfathomable.

For instance, Joseph Simitian, the American Senator of Armenian origin, visited Baku as part of the Parliamentary Commission of the U.S. Senate. His Armenian descent was no secret in Baku, still, no issues occurred in relation to “securing his safety” or “flouting the law” as was the case with the representative of a leading Russian automaker Sergey Gyurjian or the reporter of the Bloomberg network Diana Markosyan. Moreover, as reported by Musavat newspaper,168 the spiritual leader of Azerbaijan, Sheikh ul-Islam Allahshükür Pashazadeh, addressed to the Armenian Simitian a request to assist him with obtaining an entry visa for another trip to the United States.

After the Senator’s departure from Baku and his visit to Nagorno-Karabakh, he was immediately blacklisted, while other people who had been to Karabakh on numerous visits were spared this sanction.

In 2011, in the wake of a scandal over the visit to Karabakh by a journalist Sergey Buntman and his subsequent blacklisting, a fellow journalist from Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow) radio station was invited to Baku; it was the first deputy of the editor-in-chief Vladimir Varfolomeyev169 who had also been to Nagorno-Karabakh Republic back in 2003. Two years later, in 2013, after his visits to Stepanakert and Baku, Varfolomeyev too saw his name in the list.170

The astronauts Charles Duke (USA) and Claude Nicollier (Switzerland), who set foot on Moon and in Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, were also included in the blacklist of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan.171 In case of the Washington Post reporter Will Englund,172 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan announced that it was well aware of his visit to Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and had no objection. Nevertheless, despite the assurances of E. Abdullayev173 that “foreign nationals who seek official authorization from the Azerbaijani side to visit occupied territories of the country will not be included in the list”, the awareness of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan failed to save Englund’s name from appearing in the blacklist. Will Englund, in his turn, stated that in his coverage of Nagorno-Karabakh, he gave an impartial commentary on the issue and a truthful account of what he personally saw, and the capital city of Nagorno-Karabakh Republic for decades has borne the name of Stepanakert and not Khankendi, as claimed by the Azerbaijanis174.

In May 2013, a Georgian journalist Margarita Akhvlediani was detained at the airport of Baku and not allowed to enter the country, while the citizens of Great Britain who were accompanying her were allowed to gain free entry into Azerbaijan.

“Indeed, yesterday I arrived in Baku by plane at the invitation of Avaz Hasanov, Head of Society for Humanitarian Research, to hold trainings among refugees and internally displaced persons. However, I could not make it through the passport control as I was simply not allowed to pass. I had to spend almost 24 hours at the airport of Baku, without hearing any explanation. Only later did I find out that I was denied entry to Azerbaijan because of my visit to Nagorno-Karabakh. Yet, my passport contains no stamps or seals attesting my visit to Karabakh. I’m a journalist and may visit any country in my professional capacity. Interestingly, British nationals who accompanied me and had also paid a visit to Karabakh faced absolutely no claims. I studied the legislation of Azerbaijan, and unlike Georgian legislation, it does not provide for any penalty or sanction for visiting Nagorno-Karabakh. This incident is currently handled by the Embassy of Azerbaijan to Georgia, and I am also waiting for explanations from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan”, concluded M. Akhvlediani in her interview.175

The journalists from Euronews TV channel who visited Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and produced some footage covering the real daily life of the local population could also avoid blacklisting. To be fair, they were required to make amends and shoot a similar film from the Azerbaijani perspective. Peter Barabas who is the chief editor of the TV channel agreed to prepare an equivalent report from Azerbaijan but “on the same terms which we solicited from the Armenian Government, i.e. the report will be based exclusively on our editorial policy and guiding principles”, stated P. Barabas.176

It is possible to be blacklisted for a single use of the word Karabakh. A popular Daghestani singer Timur Temirov was blacklisted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan after he recorded a song named Our dear Caucasus, in which he confessed his love for Armenia and sang of its sights, including Artsakh. In his interview to Vesti.az, Timur Temirov stated that after the airing of the music video, he was denied entry to Azerbaijan: “Last year, they turned me back, and I don’t want that it happening again”.177

There have been recorded cases of removing a name from the blacklist. The removal procedure is also quite obscure and opaque; yet, past experience indicates that it takes showing some remorse and asking for forgiveness, although in certain cases, it is enough to admit verbally that the person in question visited Karabakh unknowingly or was tricked into going there (“they didn’t say where they were taking us”). However, it does not always work with everyone. Or you can hail Azerbaijan preferably by showing your dislike of Armenia; however, this requirement may be dispensed with.

After the Russian singer Katya Lel gave a concert in Karabakh and was subsequently blacklisted, she gave an interview to the Azerbaijani information agency AzerTAc where she expressed a wish to have her name off the blacklist of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan; she was allowed to give a free concert in Baku.178 A famed French actor Gerard Depardieu and Head of the Georgian Writers Union Makvala Gonashvili179 had their names removed from the blacklist after they publicly repented.

Journalists from Zerkalo newspaper set a goal of finding out what are Azerbaijan’s requirements for removing a name from the blacklist.180 To believe the press secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs E. Polukhov, there are absolutely no requirements. He clarified that placing a person’s name on the list of undesirables was not the Ministry’s responsibility: “Once we receive information that a specific person has visited Nagorno-Karabakh, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs forwards this information to the appropriate public bodies which are authorized to ban entry to the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The border guard service which is responsible for defending the country’s frontier has such a list”.

This being said, it is still unclear who makes the decision on removing a specific name from the list. E. Polukhov suggested that journalists might seek clarification on issues of their interest at law enforcement authorities, i.e. Azerbaijan’s Ministry of National Security and the State Border Service.

Following Polukhov’s advice, the journalists turned to the Ministry of National Security of Azerbaijan for an elucidation. However, the Ministry’s Head of Public Relations, Arif Babayev stated that this matter was beyond the scope of their Ministry. Next, the journalists asked the Ministry of Interior Affairs of Azerbaijan to comment on the issue. According to the Ministry’s press service represented by Orhan Mansurzadeh, their Ministry did not handle the placement or removal of names on the list of undesirables. The State Border Service of Azerbaijan communicated through the officer of its press service, Jabrail Aliyev that the name of a person was removed from the list of undesirables by the same organization which had placed the name on the list.