Kitabı oku: «Urban Protest», sayfa 2

Structure

This book describes the development of a spatial perspective on mass protests, a model which has been applied to three case studies: Kyiv, Minsk, and Moscow. It consists of ten chapters, divided into three main parts, one theoretical, one practical, and one concluding.

Part I opens in chapter 2 with a contextualisation of space and its central position in human society since the prehistoric era. It outlines a history of contention in urban public spaces, and explains why public spaces in the East Slavic region form the topic of this book.

Having established that urban public space has both a historic and a contemporary relevance, chapter 3 provides a systematic review, in two sections, of the existing research on protests and space. The first section (3.1) includes general theories within sociology and political science, and research on the specific conditions necessary for a collective action or revolution to occur. The second (3.2) looks at the various research on public (philosophy), physical (architecture, urban planning, geography), and contested space (urbanism). In the third section (3.3), an existing gap in the available research is identified. Even if connections between space and protest are discovered in the research literature, and from a variety of perspectives, none of the publications surveyed provide a systematic and generalised approach to the analysis of this causal relationship.

Chapter 4 continues the discussion of chapter 3 by providing two key definitions of mass protests (4.1) and urban public space (4.2), before stating the primary and secondary research questions of this book in full (4.3).

The theorising and development of the spatial perspective, from the conception of an idea to a complete theoretical model, are described in chapter 5. This includes the theory and approaches to theorising applied during the various stages of the model’s development (5.1), and some of the ethical considerations taken into account during the process (5.2), as well as my main reservation about developing a theory with a focus on geography. From this starting point, the development of the model is traced from its beginnings (5.4) through different stages of theorising and testing (5.5) to a description of the causal chains between urban space and mass protests employed in the final model (5.6). The project’s three case studies were written in parallel with the model’s development, and thus also reflect the various stages of the process. The first case is described as a prestudy (5.5.1), the second as a transitional study (5.5.3), and the third as the main study, demonstrating how the spatial perspective can be applied in its current form (5.7).

The causal mechanisms described in chapter five are explicated in chapter 6, including the model’s independent (6.1), intermediary (6.2), and dependent variables (6.3).

Part II consists of three chapters, each based to a large extent on the cases described in chapter 5: The prestudy of Maidan in Kyiv (chapter 7); the transitional study of October Square and Independence Square in Minsk (chapter 8); and the main study of Swamp Square in Moscow (chapter 9).

The single chapter of Part III—chapter 10—provides a final demonstration of the spatial perspective as applied to Republic Square (Place de la République), Paris, during a demonstration there on 6 January 2019 by the Yellow Vests (Fr.: Mouvement des gilets jaunes). The case study is used to demonstrate how the research questions outlined in chapter 4 have been answered, and forms the basis for arguing that the model can be used as a tool and a language to discuss spaces of contention and to provide new insights into the study of social movements and mass protests. Following a brief review of the contents, findings, and utility of this book, I then suggest a few ways in which the spatial perspective can be developed further.

1 The Ukrainian Ministry of Health later announced that the actual number of those killed was 82 (Ukrainian Ministry of Health 2014).

Part I

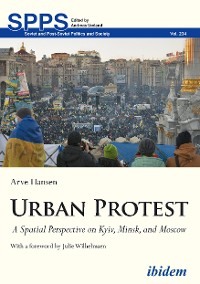

Figure 3: Maidan, Kyiv, December 2013

Photo: Arve Hansen

2 Space in Context

Human beings are cognitive creatures. We experience the world around us through our external sensory input, such as touch, smell, and sight, which our brains interpret based on our experiences, memory, and thoughts. One fundamental aspect of the experienced world is space and, consciously or subconsciously, we never stop interpreting the physical environment around us. This does not imply that we are necessarily aware of how this analysis is done, or even that it is being done in the first place. We often are unable to appreciate the full extent and impact of it or to explain how it works to a third party. Nevertheless, we are instinctively aware of our surroundings, sense their uses, opportunities, dangers, and risks, and adapt our behaviour accordingly.1

This keen sense of place has probably played a vital part in the survival of our species. When our early hominid ancestors, millions of years ago, entered new ground, instincts would be activated to provide information about the possibilities and dangers that particular space might provide. Exploring a new location, an individual would be sensitive to whether the space made them feel relaxed and safe, or alert and uneasy.

Over time, as the human capacity for social interaction evolved, space would come to be perceived not just as a place that might provide food and a chance to eat (or, conversely, a threat of being attacked and eaten), but also as a location for the increasingly complex social interactions between individuals within a group. Thus, the instinctive human perception of space would come to include information about other people and about the social interactions and relations occurring in that space. A newly arrived individual would, for example, soon sense whether this was a place to eat, relax, converse, and mate, or to be on its guard against other individuals in the group. It would know—with little conscious effort—where its allies and friends were, find the possible exits, sense whether it belonged in the group, and locate itself strategically according to its position in the social hierarchy: whether funny, loud, and boastful at the centre of the group, or reserved, quiet, and humble near one of the exits. Individuals who were oblivious to such social space would probably end up as outcasts, or worse, killed.

According to the Australian anthropologist Terrence Twomey (2014), our discovery and domestication of fire hundreds of thousands, perhaps even over a million years ago (Gowlett 2016) probably facilitated the evolution of human cooperation. Twomey explains how making a fire and keeping it going was a costly endeavour, yet the result was a good from which all the individuals in a group could greatly benefit. Hence, the domestication of fire would stimulate cooperation (Twomey 2014). We could therefore imagine that, for groups of hunter-gatherers in prehistoric times, the campfire would become one of the first dedicated spaces for social interaction. Here, people would flock together not only to eat and sleep in the relative safety from predators, insects, and cold weather, but also to process past events, discuss gains and risks, and make a plan of action for the day to come.

After the Neolithic Revolution of approximately 10 000 BCE, humans gradually started to live in fixed settlements and the new agricultural technology laid the foundation for explosive population growth (Bellwood and Oxenham 2008). In the new and increasingly urban setting, the locations of social interaction and planning would probably move from the campfire into urban spaces, such as marketplaces, town squares, or other focal points of growing villages and cities. We can find archaeological evidence from the Bronze and Iron ages, for instance, which indicate that social and deliberative spaces were valued to such an extent that they were rganizati as various forms of political institutions. Popular assemblies in urban space could be found in the Ancient Greek Agora (Anc. Greek.: ἀγορά), the Roman Forum Romanum, and the Slavic Veche (Rus.: вече); or, conversely, in the outskirts of settlements, such as the Scandinavian Thing (Icel.: þing).

However, urban spaces have some significant limitations as formal places of deliberation and public administration. Notably, the central plaza of a large city may not have enough physical space available for all people to attend, and large groups of people are often at risk of being affected by demagoguery. For these and other reasons, in most societies, public rganization moved into the remit of formal political institutions. Yet the cities’ urban spaces have remained as necessary parts of the landscape, needed in order for people to move from one place to another. Additionally, they function as places for trade, recreation, and social interaction. Urban spaces are often the location of joyful activities such as festivals and public entertainments, but also, sometimes, of floggings and executions. Some rulers might use the city’s focal point to display their might, too—for instance, in the form of army drills and parades. Moreover, although the majority of formal decisions now occur in buildings, the potential use value of urban space for people to discuss, deliberate, and decide on a course of action has not gone away.

Throughout human history, people have tended to congregate in central places in times of trouble. Such gatherings sometimes occur on the initiative of rulers to collectively find a solution to a shared problem (such as how to respond to an imminent invasion or the death of a prince). Yet, every so often, the ruling elites are themselves perceived as the problem, and the urban squares and marketplaces might be seized by the people and turned into arenas of opposition.

Figure 4: Althing, Iceland

Iceland’s form of popular assembly (Icel.: Alþingi) was first located on Thingvellir (the Assembly Fields, Icel.: Þingvellir)/Lögberg in the tenth century CE. Photo: Andrei Rogatchevski

2.1 Complexities of Urban Contention

Urban contention has a large number of aspects, and several of these are discussed in the next chapter. But there are three ways to look at and categorise urban collective actions that should be mentioned here to provide the reader with a sense of the complexity of the phenomenon: 1) the various forms of urban contention, 2) the motivations people have for action: and, 3) the local, regional, and global tendencies or waves of contention of which the collective action is part.

2.1.1 Form

One form of urban contention is the violent mob, wholly or partially controlled by powerful individuals such as politicians, religious leaders, and oligarchs. The mob has often been used as a tool to incite violence in cities against political opponents and so change the political landscape. In the Ancient Roman Republic, for example, groups of discontented plebeians often became an important force in the frequent (and often violent) transitions of power (Brunt 1966). Another example might be the veche (popular assembly) of the Medieval East Slavic Novgorod Republic (1136–1478), where the crowd were often more powerful than their prince. Historical chronicles recount how the Novgorodians, under heavy influence from wealthy boyars, sometimes removed ineffective leaders by force (Paul 2008; Evtuhov, Goldfrank, Hughes, and Stites 2004, 88–89).

Urban contention can also be seen in the uncontrolled violent crowd which, under pressure, stands up to the ruling elites and overthrows them in violent riots, uprisings, and revolutions. The French Revolution (1789–1799) is a particularly prominent example because it shows how space can both foster discontent and provide a suitable environment for insurgencies.2

Conversely, urban discontent can manifest as nonviolent protests, such as the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. (Lumsden 2000), or the 1919 May Fourth Movement at Tiananmen Square in Beijing (Wasserstrom 2005).

2.1.2 Motivation

Another way to look at urban contention is by considering the motivation for the action. The US is a fitting example to illustrate that urban contention can have a wide range of different motives, ranging from a wish to improve living conditions, e.g. the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 (De-Michele 2008), to the many movements against wars and military interventions (see for example the protests against the war in Vietnam [History.com 2019], and in Iraq [Chan 2003]). Cities in the US have also seen multiple protests for the equal rights of oppressed groups in society, such as the 1969 Stonewall Riots and the birth of the Gay Rights Movement (Kuhn 2011), the feminist movements of the 1970s (Spain 2016), and the more recent Black Lives Matter protests (Karduni 2017); collective actions aimed at causing harm, such as racially motivated violence in Southern US cities (Olzak 1990); religiously inspired protests, such as the Washington for Jesus rally in 1980 (Flippen 2011, 1–23), and social movements against economic inequality, such as the 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest movement (Gillham, Edwards, and Noakes 2013).

2.1.3 Waves

A third approach to urban discontent is to see it as waves that come and go, sweeping through periods in history, changing power structures and the layout of societies. A large number of such waves of contention have occurred throughout history in cities across the globe. In Eastern Europe, for example, we can identify at least four waves, shown here together with their political aftermath:

1917

Eastern Europe did not become part of the three European waves of revolution of the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s that followed in the aftermath of the French Revolution. But the radical new ideas of European thinkers, combined with the grievances of war and deep inequality in society, turned into a series of urban uprisings in the Russian Empire and eventually into the October Revolution of 1917. The Soviet Union was created in the aftermath of this revolution.3

1950s and 1960s

The second wave of urban discontent in Eastern Europe started during the period of thaw introduced by Nikita Khrushchev in the aftermath of Stalin’s death in 1953. A series of mass protests against poor standards of living and political repressions broke out in the streets and squares of major cities in the Eastern Bloc. Notably, uprisings and demonstrations occurred in 1953 on Leipziger Straße in Berlin (Ostermann and Byrne 2001, 163–165), in 1956 on Adam Mickiewicz Square in Poznań (Grzelczak n.d., 98–101) and on Kossuth Lajos Square in Budapest, also in 1956.4 The public spaces of cities in several of the Warsaw Pact countries also featured in the worldwide protest movements of 1968, four years after the thaw ended. 5

1985 to 1991

From the second half of the 1980s, triggered by the 1986 glasnost (transparency/openness) and perestroika (restructuring) reform policies, urban protests started to appear in the Eastern Bloc. In the Baltics, for example, protesters actively used music in what would later be known as the Singing Revolution of 1987–1991 (Smidchens 2014). Opponents of the Soviet regime rganized numerous concerts in city centres and formed a human chain between the three capitals, Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius, to demonstrate their unity in their discontent with the USSR (2014, 249). These actions inspired similar protests, notably in Ukraine (Hansen, Rogatchevski, Steinholt and Wickström 2019, 36–37). Between 1989 and 1991, the Warsaw Pact gradually fell apart as series of both nonviolent and violent anti-communist revolutions occurred in capital cities across the Eastern Bloc. Notable events include masses of East Germans tearing down the Berlin Wall in November 1989, and the failed military coup of August 1991, which was partly stopped by the masses of people who went out into the public spaces of Moscow and other Russian cities (Marples 2004, 84). The Soviet Union was dissolved later that same year.

2000s

Following a somewhat chaotic decade in the 1990s,6 a new wave of social movements and mass protests hit the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia in the 2000s (see fig. 5). Inspired by the Eastern European protests of the late 1980s, the demonstrators used nonviolent means to occupy central public squares in capital cities. The protests were often triggered by election fraud, and they demanded (and often achieved) the resignation of the elites that had managed to hold on to power after the breakup of the Eastern Bloc. The social movements of the 2000s are usually known as colour revolutions, with reference to the bright colours and symbols employed by the protesters. Although not in the former Soviet Union, the Yugoslavian Bulldozer Revolution, which overthrew President Slobodan Milošević in 2000, is often regarded as the first of the colour revolutions (e.g. by Tucker 2005).

Figure 5: Notable protests and colour revolutions in post-Soviet states in the 2000s

| Year | Country | Focal point | Name(s) | Result |

| 2003 | Georgia | In front of the Parliament (Tbilisi) | Rose Revolution | Resignation of President Shevardnadze, new parliamentary elections. |

| 2003–2004 | Armenia | Freedom Square (Yerevan) | 2003–2004 Armenian Protests | Forceful removal of protesters, legal retributions against protesters and protest organisers. |

| 2004–2005 | Ukraine | Maidan (Kyiv) | Orange Revolution | New presidential elections. |

| 2005 | Kyrgyzstan | Ala-Too Square (Bishkek) | Tulip Revolution | Resignation of President Akayev, new presidential elections. |

| 2005 | Azerbaijan | Gelebe/Galaba Square (Baku) | 2005 Azerbaijani Protests | Some concessions. “[O]fficial results for 7 or 8 of 125 parliamentary seats [were] annulled.” (Chivers 2005) |

| 2006 | Belarus | October Square (Minsk) | Kalinowskyi Square/Jeans Revolution | Forceful removal of the protest camp, legal retributions against protesters and protest organisers. |

| 2008 | Armenia | Freedom Square (Yerevan) | 2008 Armenian Protests | Forceful removal of the protest camp, protesters killed, legal retributions against protesters and protest organisers. |

| 2009 | Moldova | Great National Assembly Square (Chișinău) | Twitter Revolution | New parliamentary elections, resignation of President Voronin. |

The above three categories (form, motivation, waves) are not intended to be exhaustive, but to illustrate that “urban contention” is a multifaceted term with historic and contemporary relevance to most regions in the world. The following section serves two purposes: 1) to provide a justification for choosing Kyiv, Minsk, and Moscow as case studies for the three articles in this study; and 2) to show that space and protests are important factors which have affected, and continue to affect, the political situation in the East Slavic area.