Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

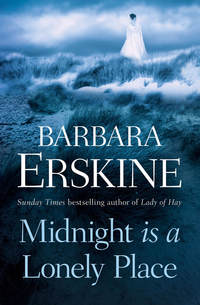

Kitabı oku: «Midnight is a Lonely Place», sayfa 3

V

His nails had cut deep welts into the palms of his hand; the veins stood out, corded, pulsating on his forehead and neck, but his silence was the silence of a stalking cat. Not a leaf crisped beneath his soft-soled sandals, not a twig cracked. Soundlessly, he parted the leaves and peered into the clearing. His wife’s long tunic and cloak lay amongst the bluebells, a splash of blue upon the blue. The man’s weapons, and his clothing, lay beside them. He could see the sword unsheathed, the blade gleaming palely in the leaf-dappled sunlight. He could hear her moans of pleasure, see the reddened marks of her nails on his shoulders. She had never writhed like that beneath him, never uttered a sound, never raked his skin in her ecstasy. Beneath him the woman he adored and worshipped would lie still; compliant, dutiful, her eyes open, staring up at the ceiling, on her lips the smallest hint of a sneer.

He swallowed his bile, schooling himself to silence, watching, waiting for the climax of their passion. His sword was at his waist, but he did not reach for it. Death at the moment of fulfilment would send them to the gods together. It would be too easy, too quick. Even as he watched them he felt the last remnants of his love curdle and settle into thick hatred. The punishment he would inflict upon his wife would last for the rest of her days; for her lover he would plan a death which would satisfy even his fury. But until the right moment came, he would wait. He would welcome her back to his hearth and to his bed with a smile. His hatred would remain, like his anger, hidden.

Watery sunlight filled Roger’s study, reflecting in from the bleak garden, throwing pale shifting lights across the low ceiling with its heavy oak beams. Greg flung himself down in his father’s chair and stared round morosely. He would never be able to paint here. Somehow he had to get Lady Muck out of the cottage – his cottage – so he could go back. She must not be allowed to stay.

The small room was stacked with canvasses and sketch pads. His easel filled the space between the desk and the window; the table was laden with boxes of paints and pencils and the general debris he had fetched down from the cottage; a new smell of linseed oil and white spirit overlaid the room’s natural aroma of old books, Diana’s rich crumbling pot pourri and lavender furniture polish. Thoughtfully he stood up. He leafed through a stack of canvasses and lifted one onto the easel, then he sat down again, staring at it.

The portrait bothered him. It was one of a series he had done over the past two or three years. All of the same woman, they were sad, mysterious; evocations of mood rather than of feature; of beauty by implication rather than definition. This was the largest canvas – three feet by four – that he had tackled for a long time and it had given him the most trouble.

He sat gnawing at the knuckle of his left thumb for several minutes before he glanced round for brush and palette. It was the colours that were wrong. She was too hazy; too indistinct. Her colouring needed to be more definite, her vivacity more pronounced. He stood close to the canvas, leaning forward intently, and stabbed at it with the brush. He had made her too beautiful, the bitch, too seductive. He ought to paint her as she was – a whore; a traitor; a cat on heat.

His tongue protruding a little from the corner of his mouth, he worked furiously at the painting, blocking in the face, shading the planes of the cheeks, sketching lips and eyes, touching in the line of the hair, his anger growing with every brushstroke.

It was a long time before he threw down the brush, wiping his hands carelessly on the front of his old, ragged sweater. He stood back and stared at his handiwork through narrowed eyes, aware that as the sun moved lower in the sky, slanting first across the estuary and then across the bleak winter woods, the light was changing once again and with it her face. He glared down at the palette he had slid onto his father’s desk, aware that the anger was leaving him as swiftly as it had come and wondering, not for the first time, where it came from.

VI

Turning the car off the road Kate found they were bumping along an unmade track through a wood. Before them the sky, laced with shredded, blowing cloud had that peculiar intensity of light which denotes the close proximity of the sea.

‘I hope we don’t have to go far down here,’ she commented, slowing to walking pace as the small vehicle grounded for the second time on the deep ruts. Winding down the window she took a deep appreciative breath of the ice-cold air. It carried the sharp, resinous tang of pine and earth and rotting leaves.

‘I’m afraid it gets worse.’ Bill grimaced. ‘And you’ll have to leave your car at the farmhouse. Roger or Greg will run all your stuff up to the cottage in their Land Rover.’

The track forked. In front of them a rough wooden gibbet held two or three fire brooms – threadbare, broken. She brought the car to a standstill. ‘Which way?’

‘Right. My place is up there to the left – about half a mile. The farmhouse is down here.’ He gestured through the windscreen and cautiously she let in the clutch once more. The track began to descend sharply. They bounced again into the ruts as the wood grew more dense. Pine was interspersed with old stumpy oaks, hazel breaks strung with ivy and dried traveller’s joy and thickets of black impenetrable thorn.

The farmhouse itself stood at the edge of the woods, facing east across the saltings. Behind it a thin strip of field and orchard allowed the fitful sunshine to brighten the landscape before another wood separated the farmhouse gardens from the sea. There was no sign of any cottage.

She halted the car beside a black-boarded barn and sat for a moment staring out. The farmhouse was pink washed, a long, low building, covered in leafless creepers which in the summer were probably clematis and roses. Even in the depths of winter the place looked extraordinarily pretty.

‘What a lovely setting.’

‘Not too wild for you?’ Bill glanced beyond the farmhouse to the mudflats. As far as the eye could see there was nothing but mud and water and grey-green stretches of salting. A stray low shaft of sunlight shone from behind them throwing a sunpath over the mud towards the water. The rich colour lasted a moment and then it had gone.

Bill opened the car door allowing biting, pure air into the warm fug. ‘Come on. It will start getting dark soon. I think we should get you settled in.’

Kate surveyed her hosts as she shook hands with them. Roger and Diana Lindsey were both in their fifties, she guessed. Comfortable, quiet, welcoming. She found herself responding immediately to their warmth.

‘I thought you would like some tea here before you go up to the cottage,’ Diana said at once, ushering her towards the sofa. ‘Make yourself comfy – move those cats – and then I’ll give my son a call. He is going to take your stuff up there for you. It’s a long walk carrying luggage.’

‘And she’s got a heap of it,’ Bill put in. He was standing with his back to the fire, his palms held out behind him towards the smouldering logs. ‘Computers and stuff.’

‘Oh, my goodness.’ Diana frowned. ‘In which case you’ll certainly need help.’

‘Where is the cottage?’ Kate, while enjoying the soporific comfort of the tea and the warmth of the fire, was eager to see it. Over the last couple of days her excitement, though partly dampened by the thought of how much she was missing Jon – a thought she had deliberately tried to erase – had been intense.

‘It’s about half a mile from here. Through the wood. You’re right on the edge of the sea out there, my dear. I hope you’ve brought lots of warm clothes.’ Solicitously Diana refilled Kate’s cup, inserting herself between Kate and the staircase door where she had spotted a movement. The kids were spying. No doubt any moment now they would appear. She sighed. Kids indeed. She meant Alison and Greg. Patrick would no doubt be upstairs by now with his computers and would not reappear until called for supper. It was her elder son – a grown man, old enough to know better – and her daughter, who were, if she were any judge of character, going to cause trouble.

She glanced over her shoulder at Roger. ‘Give Greg a call. I want him to help Miss Kennedy –’

‘Kate, please.’

‘Kate.’ She flashed Kate a quick smile. ‘He could start loading her stuff into the Land Rover.’

‘I don’t want to be a nuisance.’

‘You won’t be.’ Was it Kate’s imagination, or was there a certain grim determination in the way Diana said those words?

Greg, when called, turned out to be a man in his late twenties or early thirties, Kate guessed, which made him around her age or slightly younger. His handsome features were slightly blurred – too many beers and too little care of himself – and his thick pullover was smeared with oil paint. He shook hands with her amiably enough but she sensed a hint of reserve, even resentment in his manner. It was enough to make her question her first impression that here was a very attractive man.

‘I’m sorry. It’s a nuisance for you to have to drive me to the cottage,’ she said. She met his eyes challengingly.

‘But necessary if our tenant is to be safely installed,’ he replied. His voice was deep; musical but cold.

Bill must have felt it too. She saw him frown as he levered himself to his feet from the low sofa. ‘Come on, Greg. I’ll give you a hand. Leave the others to finish their tea, eh?’

As the front door opened and the two men disappeared into the swiftly-falling dusk, a wisp of fragrant apple smoke blew back down the chimney.

‘You can park your car in the barn, Kate,’ Roger said comfortably. He leaned back in his chair, stretching his legs out towards the fire. ‘It’ll be out of the worst of the weather there. Pick it up whenever you want, and if you have any heavy groceries and things at any time give us a shout and we’ll run them over for you. It’s a damn nuisance the track is so bad. I keep meaning to ask our neighbour if he’ll bring a digger or something up here and level it off a bit, but you know how it is. We’ve never got round to it.’

‘I’ve come for the solitude.’ Kate smiled at him. ‘I really don’t want to be rushing up and down. I’ll lay in some stores at the nearest shop and then I’d like to cut myself off from the world for a bit.’ The thought excited her. The great emptiness of the country after London, the sharp, clean air as she had climbed out of the car, had heightened her anticipation.

‘You’ll be doing that all right. Especially if the weather is bad,’ Roger gave a snort which might have been a laugh. ‘There is a telephone over there, however. You might find you’re glad of it after a bit, but if you want peace you’d better keep the number quiet.’ He looked up as the door opened.

‘All loaded.’ Bill grinned at them. ‘I think what I’ll do, if you don’t mind, Kate, is begin to make my way back to my place. It’s quite a walk from here. I’ll leave you to Greg and I’ll wander over tomorrow morning if that’s all right. Then I can show you the way back on foot in daylight, and perhaps we can have a drink together before you drop me off in Colchester to catch the train for London.’

The Land Rover’s headlights lit up the trees with an eerie green light as they lurched slowly away from the farmhouse into the darkness. Kate found herself sliding around on the slippery, hard seat and she grabbed frantically at the dash to give herself something to hold on to, with a worried thought for the computer stored somewhere in the back.

‘Sorry. Am I going too fast?’ Greg slowed slightly. He glanced at her. He had already taken note of her understated good looks. Her hair was mousy but long and thick, her bones good, her clothes expensive, but he got the feeling she wasn’t much interested in them. The undeniable air of chic which clung to her was, he was fairly sure, achieved by accident rather than design and the thought annoyed him. It seemed unfair that she should have so much. ‘I take it you’re not the nervous type. I can’t think of many women who would want to live out here completely alone in the middle of winter.’

Kate studied his profile in the glow of the dashboard lights. ‘No. I’m not the nervous type,’ she said. ‘I enjoy my own company. And I’ve come here to work. I don’t think I’ll have time to feel lonely.’

‘Good. And you’re not afraid of ghosts, I hope.’

It had been Allie’s idea, to attempt to scare her away with talk of ghosts. It was worth a try. At least until he thought of something better.

‘Ghosts?’

‘Only joking.’ His eyes were fixed on the track ahead. ‘This land belonged once to a Roman officer of the legion, Marcus Severus Secundus. There’s a statue of him in Colchester Castle. A handsome bastard. I like to think he strolls around the garden sometimes, but I can’t say I’ve ever seen him.’ He grinned. Not too much too fast. The woman wasn’t a fool. Or the nervous type, obviously. ‘I’m sure he’s harmless.’ He narrowed his eyes, concentrating on the track.

Beside him Kate smiled. Her excitement if anything increased.

The cottage when it appeared at last seemed to her delight to be a miniature version of the farmhouse. It had pink walls and creeper and was, she could see in the headlights as they pulled up facing it, a charmingly rambling small building with a peg-tiled roof and smoking chimney. Beyond it she could see the dull gleam of the sea between towering banks of shingle. Leaving the headlights on, Greg jumped down. He made no effort to help her, instead going straight round to the rear of the vehicle, leaving her to struggle with the unfamiliar door handle. When she at last managed to force the door open and jump down, he straightened, his hair streaming into his eyes in the wind. Before she realised what he was doing, he threw a bunch of keys at her. She missed and they fell at her feet in the dark.

‘Butterfingers.’ The mocking words reached her through the wind. ‘Go and open the front door, I’ll carry this stuff in for you and then I can get back.’

The door had swollen slightly with the damp and she found she had to push it hard to make it open. By the time she had done it Greg was standing impatiently behind her, his arms full of boxes. She scrabbled for a light switch and found it at last. The light revealed a small white-painted hall with a staircase immediately in front of her and three doors, two to the left and one to the right.

‘On the right,’ Greg directed. ‘I’ll dump all this for you and you can sort it out yourself.’

She opened the door. The living room, low-ceilinged and heavily beamed like its counterpart in the farmhouse, boasted a sofa and two easy chairs. In the deep fireplace a wood burning stove glowed quietly, warming the room. The other three walls each had a small-paned window, beyond which the black windy night was held at bay by the reflection of the lamp as she switched it on. She crossed and drew the curtains on each in turn. By the time she had finished Greg had brought in another pile of stuff.

‘Well, that’s it,’ he said at last. He had made no attempt to tidy it or distribute things for her. All were lumped together in a heap in the middle of the rug. ‘If you need anything you can tell us tomorrow.’

‘I will. Thank you.’ She gave him a smile.

He did not respond. With a curt goodnight he turned and ducked out of the front door, pulling it closed behind him. Resisting a childish urge to run to the window and watch him leave she saw the glow of the headlights brighten the curtains for a moment as they swept across them, then they disappeared. She was alone.

Walking out into the hall she pulled the door bolt across and then turned back. The sudden wave of loneliness in the total silence was only to be expected. She sighed, looking round. Somehow she had expected that Bill would be with her this first evening. Or that the new landlord would invite her over for supper.

It had all been such a rush up until now. The packing, the storing of her stuff, borrowing books from the London Library, arranging her new life, separating herself from Jon; she had had little time to think and she had welcomed her exhaustion each evening. It meant she did not dwell on things. Here there would be plenty of time to dwell unless she was very careful. She straightened her shoulders. There would also be plenty of time to work, but first she would explore her new domain.

The cottage was very small. Downstairs there was only the one living room with a small kitchen and even smaller bathroom next to it. Upstairs there were two bedrooms, almost identical in size. Only one had a bed. In that room someone had made an attempt at cosiness. There was a chest of drawers and a small Victorian chair upholstered in rubbed gold velvet, with a couple of soft cushions tossed onto it. There was a new rug on the sloping floor and a wardrobe, which touched the low beamed ceiling. Inside was a row of wire hangers. Kate went downstairs again. Her initial excitement and sense of adventure was slipping away. The silence oppressed her. Taking a deep breath she went into the kitchen and reached for the kettle. While it boiled she lugged her two suitcases upstairs and left them. She would hang up the dresses and two skirts which she had brought with her later. All her other clothes – jeans, trousers, sweaters – she could stuff into the small chest of drawers tomorrow. She did not feel like unpacking this evening.

After sorting out some of her books and papers, stacking them all neatly on the table in the living room, and putting the food and the bottle of Scotch she had brought with her into the kitchen cupboards she felt too tired to do any more. She made herself some tea, selected a couple of tapes and sat down, exhausted, on the sofa near the fire, her feet curled up under her. Her hands cupped around the mug, she sat listening to the strains of Vaughan Williams on her cassette player, strangely aware of the giant heave and swell of the sea outside beyond the shingle bank, even though she could not hear it.

She should have felt pleased with herself. She was in the country at last. She was ready to begin work. She had the peace and quiet she desired – Greg’s attitude had not left her in any doubt that her privacy would be respected – and yet there was a nagging sadness, a feeling of anticlimax which had not a little to do with Jon, curse him. Only three weeks before, she had been living with him, researching the book, settled, a Londoner at least for the foreseeable future, and now here she was in a small cottage on the wild north-eastern coast of Essex with strangers for neighbours, no money, no man, no fixed abode and only Lord Byron for company.

Glancing at the floor where her boxes of books lay in a pool of lamplight she stood up again restlessly. She went over and, groping for her glasses in the pocket of her jeans, she began wearily to tear the sticky tape from the top of one of them. She must stay positive. Forget Jon. Forget London. Forget everything except the book.

The door banging upstairs made her jump. She glanced up at the ceiling and she could feel her heart thumping suddenly somewhere in the back of her throat. For a moment she did nothing, then slowly she straightened.

There was no one in the house so it must have been the wind, but at the foot of the stairs she paused, looking up into the darkness, the thought of Greg’s legionnaire suddenly in the forefront of her mind.

Taking a firm grip on herself she walked up onto the landing. Both doors stood open as she had left them. Switching on the light she peered into the bedroom where earlier she had put her cases side by side near the cupboard. She looked round the room, satisfied herself that nothing was amiss and turned off the light. She repeated the action across the landing, staring round the empty bedroom, her eyes gazing uncomfortably at the two windows which were curtainless. The glass reflected the cold light of the central naked bulb and she was very conscious once again of the blackness of the night outside.

Frowning, she went downstairs. There had been nothing that she could see to account for the noise. She peered into the bathroom and the kitchen and then turned back to the living room.

The room was distinctly chilly. Walking over to the woodburner she peered at it doubtfully and, seeing the reassuring glow from within had disappeared, she stooped and reached for the latch. The metal was hot. She swore under her breath and looked round for something to pad her hands. Finding nothing she tugged at her sleeve and, wrapping the wool of her jersey around her fingers, she jiggled the latch undone and swung the doors open. The stove contained nothing but a bed of embers.

She glanced round but she had already realised that her tour of the cottage had yielded no coal; no log basket. She had grown spoiled living in London; the subject of heating had never crossed her mind. Central heating arrived for her these days at the flick of a switch. The hot water and heating in this cottage, it dawned on her suddenly, probably all depended on this small stove. Why hadn’t Greg mentioned it? Surely the first thing he should have told her was how to heat the place. She shook her head in irritation. The omission was probably deliberate. She would have had to be very dense not to have sensed his hostility and resentment. Teach the townie a lesson. Well, if the townie wasn’t going to freeze to death she would have to find some fuel from somewhere. A swift search produced one box of matches in the kitchen drawer, – thank heaven for that. As a non smoker it had never crossed her mind to bring matches. But there were no fire lighters, and there was no torch. There was nothing for it. Cursing herself for her own stupidity she realised she was going to have to explore outside in the dark.

Firmly putting all thoughts of the unexplained noise out of her head, she pulled on her jacket and gloves and with some reluctance she walked into the hall, unbolted the front door and pulled it open, fastening the latch back as she peered out into the darkness.

The wind caught her hair and pulled it back from her face, searing her cheeks. It was fresh and sharp with the scent of the sea and the pine woods which crowded across the grass towards her. She stood still for a moment, very conscious that she was silhouetted in the doorway. Reminding herself that there was no one watching she stared out at the path of light which ran from her feet in a great splash along the track before it dissipated between the trees. On either side of it the darkness was intense. She could see nothing beyond the muddy track with its windblown grasses and tangle of dead weeds.

Reluctantly, she stepped away from the door and began to walk along the front of the cottage, one hand extended cautiously in front of her touching the rough plastered walls. As her eyes grew used to the dark she could see the stars appearing one by one above her, and patches of cloud, pale against the blackness, and she became aware slowly of the sea shushing gently against the shingle in the distance and the wind sighing in the trees. She was straining her eyes as she reached the corner and peered round. Half way along the wall there was a small lean-to shed which must surely be some kind of fuel store. Moving a little faster as her confidence increased, she felt her feet grow wet in the grass.

Her fingers encountered the boards of the lean-to at last – overlapping, rough, splintery through her gloves. She groped her way around it until she came to the open doorway where she stopped, hesitating. The entrance gaped before her, the darkness intensely black and impenetrable after the luminous dark of the night, but she could smell the logs. Thick, resinous and warm, the scent swam up to her. Stooping, she groped through the doorway. Her hands met nothing but space. She reached out further and suddenly her fingers closed around something ice cold. A handle. Whatever it was slipped from her grasp and fell to the ground with a clatter. She stooped and picked it up. A spade. It was a spade. Leaning it against the wall, she took a cautious step forward, bending lower, and found herself right inside the shed. There at last her groping fingers encountered the tiers of stacked logs, their ends sharp, angled, their sides rough and rounded. Cautiously she pulled at one. The whole pile stirred and she leaped back. ‘From the top, you idiot.’ She found she had actually spoken out loud and the sound of her voice was somehow comforting. Straightening a little, she raised her hands, groping for the top of the pile and one by one she reached down four logs. That was all she could carry. Clutching them against her chest she stumbled out of the shed backwards and retraced her steps towards the corner of the wall. Once there the stream of cheerful light from the hall guided her back to the front door. She almost ran inside and throwing the logs down on the floor she turned and slammed the door shut, shooting the bolt home.

It was only as she looked down at the logs, covered in sawdust and cobwebs that she realised how frightened she had been. ‘You idiot,’ she said again. Shaking her head ruefully she began to pull off her anorak. What had she been afraid of? The silence? The wood? The dark?

She had been afraid of the dark as a child in her own little bedroom next to Anne’s in their Herefordshire farmhouse. Night after night she would lie awake, not daring to move, hardly daring to breathe, her eyes darting here and there around the room, looking – looking for what? There was never anything there. Never anything frightening, just that awful, overwhelming loneliness, the fear that everyone else had left the house and abandoned her. Or died. Had her mother guessed in the end, or had she confessed? She couldn’t remember now, but she did remember that her mother had given her a night light. It was a china owl, a white porcelain bird with great orange claws and huge enigmatic eyes. ‘You’ll scare the child to death with that thing,’ her father, a country doctor with no time for cosseting his own family, had scoffed when her mother produced it from the attic, but Kate had loved it. When the small night-light candle was lit inside it the whole bird glowed with creamy whiteness and its eyes came alive. It was a kind bird; a wise bird; and it watched over her and kept her company and kept the spooks at bay. When she was older the owl had remained unlit, an ornament now, but her fear, tightly rationalised and controlled, had remained. Sometimes, even when she was a student at university, she had lain in her room in the hall of residence, the sheet pulled up to her chin, her fingers clutched in the pillow she was hugging to her chest as she stared at the dark square of the window. The fear had gone now. Only one hint of it remained. She always opened the curtains at night. With them closed the darkness gave her claustrophobia. Jon had laughed at her, but he had conceded the open curtain. He liked it open because he loved to see the dawn creeping across the London roofs as the first blackbirds began to whistle from the television aerials across the city.

Well, that Kate was grown up now, and on her own and not afraid. Pulling herself together, she gathered up the logs and, walking through into the sitting room, she stacked them neatly in the fireplace beside the stove. Opening it again she peered in. The embers were very low. She looked at the logs thoughtfully. If she put one of those in it would just smother the small remaining sparks and put the whole thing out. She had no fire lighters. What she needed was newspaper and some dry, small twigs to rebuild the fire. She stared round.

In the kitchen the vegetable rack in the corner was lined with newspaper. She grabbed it, showering a residue of mud from long gone potatoes over the kitchen boards. There was enough to crumple into four good-sized wads. Stuffing them in around the log she lit it and closing the doors, slid open the damper. The sudden bright blaze was enormously satisfying but she held her breath. Would the paper burn and then leave the log to go out?

She glanced over her shoulder at the room and shivered. It had lost its appeal somehow. Her lap top computer and printer lying on the table rebuked her; the boxes of filing cards, the notebooks, the cardboard boxes full of books. She glanced at her watch. It was eight o’clock. She was hungry, she was tired and she was cold. A boiled egg, a cup of cocoa and a hot bath, if the wood-burner could be persuaded to work, and she would go to bed. Everything else could wait until morning. And daylight.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.