Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Land Rover: The Story of the Car that Conquered the World»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2016

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Text © Ben Fogle 2016

Photographs © Individual copyright holders

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material, the author and publisher would be grateful to be notified of any errors or omissions in the above list that can be rectified in future editions of this book.

Ben Fogle asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

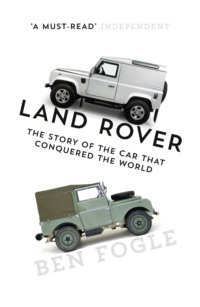

Cover photographs: bottom © Matthew Ward/Getty Images; top © JLR Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008194222

Ebook Edition © October 2016 ISBN: 9780008194239

Version: 2017-05-04

DEDICATION

To Willem

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE

INTRODUCTION

Chapter One: A LOVE STORY

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER – PART I

Chapter Two: THE RANGE OF ROVER

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER – PART II

Chapter Three: RIOT ROVER

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER – PART III

Chapter Four: FIGHTING ROVER

Chapter Five: KAHN AND THE ART OF LAND ROVER MAINTENANCE

Chapter Six: WEIRD ROVER

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER – PART IV

Chapter Seven: CRUISIN’ FOR A BRUISIN’

Chapter Eight: LANDED ROVER

Chapter Nine: DEFENDER OF THE LAND

Chapter Ten: MARLEY AND ME

Chapter Eleven: SEA ROVER

Chapter Twelve: LAND ROVER HEAVEN

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER – PART V

Chapter Thirteen: LANDY WORLD

Chapter Fourteen: THE CONQUERER

Chapter Fifteen: THE AFFAIR

CONCLUSION

EPILOGUE

PICTURE SECTION

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

LAND ROVER

The Series I, II, IIa, III, 90, 110 and Defender are all members of the iconic ‘boxy’ Land Rover genre, first produced in 1948, with the current version called Land Rover Defender. To avoid any confusion, in this book I will sometimes refer to them all using Defender as a collective noun. Please don’t hate me.

Lode Lane, Solihull is a flurry of activity. The brick walls are still covered in camouflage paint to disguise the factory from German air raids. The waters of the Birmingham canal flow close by, ready to extinguish any fires from falling bombs. Nearby a field has been transformed into a ‘jungle track’ to test the vehicles. On the factory floor inside, a team of workers are riveting aluminium plates and fixing axles to chassis on cars in various states of deconstruction. This is the famous Solihull Land Rover factory and the workmen are building some of the most iconic cars ever built, the Land Rover Series I, a car that changed the world. But this is not 1948. It is 2016 and I am watching third-generation factory workers making Series I vehicles on the same patch of land that their grandfathers had once done.

Just a few months before, the world had mourned as the very last Defender, the evolution of the Series I, rolled off the factory line. The lights went out on 67 years of iconic history. It had been the end, but now I was back at the very beginning for the rebirth. Where most evolve and advance, here at Lode Lane, workers were using decade-old tools and technology to regress to a simpler time. To make a vehicle born out of post-war rationing to help a country rebuild. This is the reborn project at Land Rover where buyers can spend more money on a ‘new’ 68-year-old vehicle than a top-of-the-range sports car.

As I bounced, cantilevered and splashed along the very same ‘jungle track’ once used by the Wilks brothers to demonstrate the capabilities of these workhorse vehicles, I couldn’t help but marvel at the ageless charm of these iconic cars. Regressive progression. Nostalgic advancement. The new old. Was this the rebirth? Had the Land Rover ever really died? Or was this really the resurrection we had all dreamed of?

It is an oxymoron but a fitting metaphor for the story of the greatest car ever made.

INTRODUCTION

‘Do not go where the path may lead,

go instead where there is no path and leave a trail’

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

At 9.30am on 29 January 2016, the 2,016,933rd Defender rolled off the production line at Land Rover’s factory at Lode Lane, Solihull, on the outskirts of Birmingham. It marked the end of 67 years of continuous production of the world’s most famous vehicle. The final Defender.

In all those years, the workhorse Defender had served farmers and foresters, armies and air forces, explorers and scientists, construction and utility companies – in fact, everyone who needed a good, honest vehicle that would do a good, honest job anywhere in the world. And there were a lot more people who bought one just for fun, too – for its sheer brilliant off-road ability and austere utilitarian attitude that made it so different to the rest of today’s homogenised, jelly-mould automotive offerings.

‘Jerusalem’ was sung through the factory line as generations of engineers, mechanics and factory line workers paid tribute to the Land Rover Defender. This was a funereal send-off for a much-loved car that had conquered the planet. Media, journalists and film crews had descended from around the world to record this death knell. The world held its breath as the last ever Defender was driven silently out of the building.

This was an end that was marked by tears and sorrow, as Land Rover enthusiasts bade farewell to a familiar friend and the historic production line that had produced it fell silent.

The world mourned. This was the day the real Land Rover, the successor to the Wilks brothers’ 1948 original, died.

It is said that for more than half the world’s population the first car they ever saw was a Land Rover Defender. As quintessentially British as a plate of fish and chips or a British bulldog, the boxy, utilitarian vehicle has become an iconic part of what it is to belong to this sceptred isle. It is a part of the stiff-upper-lipped British psyche; it never complains, and neither do we.

You climb into a Land Rover – literally; in fact some people even need ropes to hoist themselves up into the rigid seats. The doors don’t seal properly, and freezing cold rainwater, overflowing from the car’s gutter (they really do have a gutter) cascades down your neck as the flimsy aluminium door invariably closes on the seat belt that dangles out of the door. The dashboard consists of a series of chunky black buttons and two analogue dials. Without heated seats, climate control options are freeze or fry. The windows ALWAYS mist, even if you hold your breath. I have to pull up a metal antenna from the bonnet to pick up radio, which I can only receive while driving at 30mph. If I crank her up to her limit of 60mph, the noise from the engine, gearbox, transfer box, differentials, tyres and the wind is deafening, and too loud to have a conversation let alone listen to anything from the speakers. There is no coffee-cup holder or hands-free. The gears grind and the seats cannot be tilted.

So on the face of it there is not much going for the Defender. It is noisy, uncomfortable, slow, uneconomical and, according to the USA, dangerous. So why is it that I, along with millions of other people around the world, am so hopelessly, obsessively in love with this car?

The Land Rover is an integral part of the fabric of our society, a part of the furniture. Nothing lasts forever, but some things come close. The Defender has survived the decades largely unchanged. It transcends fashion while somehow epitomising it. It has an ability to neutralise rational thought or expectation, and it has avoided the homogenisation of our vehicles in modern times.

The Defender is a beacon of safety and security, too. It is favoured by the military, the police, the fire service, NGOs, the UN, the Royal Palace, the Special Forces and explorers alike. These vehicles have discovered new regions, won wars and saved lives. Across the world, the Land Rover symbolises durability and Britishness, with her diversity and rigidity. It is estimated that three-quarters of all Land Rovers ever built are still rattling noisily across country somewhere in the world.

The Defender is a national treasure. We are reassured by its understated presence. It inspires a second glance but never a stare. Unshowy, unpretentious and classless, it is the car in which you can arrive at Buckingham Palace, a rural farm or an inner-city estate.

Over the years I have encountered Land Rovers in the farthest corners of the world. From steamy tropical jungles to remote islands, I have bounced across lonely landscapes in dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Land Rovers, many of them decades old.

Around the world, the Land Rover has become as much a part of the African savannah as acacia trees and elephants. The UK was still a colonial power at the Defender’s inception, and the car quickly spread across the Empire; from Tristan da Cunha, where a lone policeman patrols the island’s one-mile road in his trusty Defender, one of only a handful of vehicles on the island, to the Falkland Islands, which boast the world’s highest per capita Land Rover ownership – one for each of the 2000 residents who live there, earning itself the moniker Land Rover Island.

I have driven through the muddy trails of the Amazon basin and across the deserts of Chile in ancient Land Rovers bound together with baler twine. When my young family first came to visit me while I was working in Africa, there was never any question that we would embark on an expedition across the muddy plains of the Serengeti in anything other than a Defender. It always seems incredible that these international workhorses that have crossed some of the most challenging of landscapes in remote corners of the world originated from a former sewing-machine factory in Solihull, near Birmingham. Such an inauspicious birthplace for arguably one of the world’s most iconic vehicles.

When I drive through London in my Land Rover I get stopped not for my autograph or a selfie but for a photograph of my car. I have lost count of the number of notes slipped under the windscreen wiper with offers to buy my beloved car. The children love it. The dogs love it – and so do two million other people in the world.

Everyone from Fidel Castro to the Queen drives a Land Rover Defender. Idris Elba made his entrance at the 2014 Invictus Games’ opening ceremony aboard a trusty Defender. Ralph Lauren, Kevin Costner and Sylvester Stallone all drive the rugged vehicles. And now, after 67 years and two million vehicles, the Land Rover Defender has ceased production. It is ironic that the vehicle is more popular in death than it was in life. Interest has reached fever pitch for this icon of Britishness; it is a vehicle that transcended its original remit to knit itself into the fabric of the nation that created it.

A vehicle that can drag a plough, clear a minefield and carry royalty, the Land Rover Defender transcends the rapidly changing world in which we live. As cars become rounder, curvier and shinier, the Land Rover Defender still looks like a child’s drawing of a car, with its boxy shape. To climb into a Defender is like stepping back in time into a simpler, classier world.

The Defender was a car that didn’t just defy the fickle face of fashion but also changing mechanisation and economics. It was a car that was handbuilt until the end. It took 56 man hours to construct just one vehicle. Two original parts have been fitted to all soft-top Series Land Rovers and Defenders since 1948: the hood cleats and the underbody support strut – but these are just two of the over 7000 individual parts that make up each Defender.

This is a car that is instantly recognisable from its wing mirrors to its wings. Indeed, workers on the Land Rover production line have their own nicknames for parts of the vehicle: for example, the door hinges are known as ‘pigs ears’ and the dashboard is the ‘lamb’s chops’.

So what is it about this vehicle that has spawned such an obsessive, loyal following? How did the Land Rover so successfully take over the world? In some ways the Defender mirrors many of our national traits; stiff-upper-lipped and slightly eccentric. In the spirit of the great British explorers Scott, Shackleton, Cook, Livingstone, Fawcett and Fiennes, the Land Rover was a twentieth-century progression of the age of exploration.

The car has spawned an industry that includes dozens of publications, car shows and even model cars tailored to the passion of those who dedicate their lives to the Land Rover. In order to understand why this car is such a national treasure and excites such passion, I decided to embark on a road trip of my own in my trusty Land Rover to meet the people who live for this marque – the enthusiasts, the designers, the military, the police and the explorers who glory in this bastion of quintessential Britishness.

A Land Rover is a living breathing thing. The vehicles become characters. We name them. We learn their unique quirks and foibles. It is a sort of love affair. I know plenty of men who remember more about their old beloved Land Rovers than they do their ex-girlfriends. These cars seduce us with their charm – they are not supermodels, they are dependable, robust and loyal. There is a unique and almost unquantifiable relationship with a Land Rover. It is an emotional attachment like no other. How can a man-made object have such power over us?

Every Land Rover has its own unique story to tell. Here, in these pages, is the story of the world’s favourite car and how it conquered the planet and the hearts and souls of those who inhabit it … and me.

CHAPTER ONE

A LOVE STORY

You never forget your first Land Rover. It was a rusty grey pick up that seemed to be held together with baler twine. The doors didn’t close properly and baler twine was doing the job of holding them shut. Inside, her seats were ragged and torn, transformed into a fabric reminiscent of Emmental cheese by the farm rats. The front windscreen was cracked and there was a large hole where a stereo had once sat. A thin coat of dust coated the interior and an even thicker layer of mud swamped the footwells. Various gloves and farm tools had been wedged into any spare space. She had a sort of musty, fuely smell that overwhelmed the senses.

On starting, she would rattle and vibrate violently. A thick black cloud of smoke would temporarily envelop the whole car with a toxic cloud of diesel fumes that threatened to choke you as it seeped through the gaping seals where the doors failed to close.

I must have been about 9 or 10 years old; I was on a farm in West Sussex where my parents had rented a tiny cottage, which was next to a working beef and dairy farm that the farmer operated with the help of an ancient Land Rover. I loved that smelly old broken vehicle, built purely for functionality.

So I have a confession to make. My first car was not a Land Rover. My parents didn’t drive one, nor did I learn to drive in one. Truth be told, I’m not even that into cars. I suppose to understand how I have come to write a book about the Land Rover, I should begin by exploring my own history with the automobile.

Our first family car was an ambulance. Not any old ambulance, but an animal one. My father, a vet, bought a Honda camper van that he converted into the ‘Mobile Animal Clinic’, a slogan which was emblazoned down the side in green ink. He wasn’t allowed blue flashing lights so the van had a green one instead. She had a little operating table in the middle and oxygen tanks around the sides. Although she was technically a caravan or a mobile home, she was like a little box fitted behind a tiny cab. The seats in the back were configured around the operating table, which meant that not only could we use it to do our homework on the way home from school but we could play endless games of monopoly during long car journeys. She was, without doubt, the most distinctive vehicle on the school run.

Sad was the day when my father retired our little animal ambulance, to be replaced by the Space Cruiser, with its state-of-the-art electric retractable roof. At the time, Toyota was one of the most advanced vehicle manufacturers in the world. Those were the days when Japanese vehicles were really coming into their own, and I think my father had been seduced by the Japanese during many of his lecturing tours. Everything in the Space Cruiser was electric – windows, sunroof – I can still recall my sisters and I standing on the back seat, with our heads protruding through the open roof as we drove through the country lanes of Sussex. Of course, driving regulations and safety requirements were a little more relaxed in the 70s; this was still the era of non-obligatory seat belts and of rear-facing seats in Mercedes-Benz. My abiding memories were of dozens of children crammed into cars and wedged into seats, often sitting on laps, heads lolling out of the open windows. Ah, those were the days!

Alongside the practical vehicles that our family owned, my mother had a lifelong love affair with the Italian Alfa Romeo. Her first was a blue model which she lovingly drove for nearly 20 years until she replaced it with a red Alfa, complete with spoilers and fins. My father could never understand her passion for the Alfa; they were expensive to run and, in his eyes, they weren’t even particularly good cars. My mother never agreed. She loved her Alfa.

Apart from my mother’s passion for the Alfa, cars were not a Fogle family obsession. They were merely functional; a means of getting from A to B or for transporting wounded animals.

One of my friends had a father who owned a Caterham. I can still remember the joy and exhilaration of being driven down a dual carriageway at more than 100mph with my head sticking out, free in the open air of the convertible. Bugs stung against my cheeks as we sped across Dorset.

When I turned 17, I decided it was time to get my driver’s licence. Looking back, I didn’t go about it in a particularly clever manner, though. Most people think logically about such important milestones and plan it with their family’s help. I was away at boarding school and short of funds so I decided to do one occasional driving lesson at a time, and then do another one once I had saved up enough money. This system worked well at first, but soon having just one lesson a month began to have detrimental effects. I have never been a quick learner and whenever I had a lesson it felt as if I was starting from scratch. This soon became apparent when I failed my first test, and then the second and the third and the fourth …

It took seven tests before I finally passed. I think this story nicely illustrates several points. First, that I am quite a stubborn individual, and second, that I really wasn’t into cars.

For the first year after I passed my test my father kindly lent me the silver-bullet Toyota Space Cruiser whenever I needed transportation. It was without doubt the most uncool car to be seen at the wheel of, but it did the job and I can remember driving piles of friends down to Devon and Cornwall in it. It was, as my father often reminded us, very ‘functional’.

The first car that I owned myself was a grey Nissan Micra. It was the archetypal bland, homogeneous car, but it was a very generous eighteenth-birthday gift from my father, who quite rightly pointed out that it was, as ever, economical and functional. My mother had tied a giant red ribbon into a bow on the roof when they presented it to me. I climbed in immediately and drove it to Hyde Park in Central London – and straight into a red Volvo. Within an hour of getting my first car it was a near write-off and was being towed away by a recovery vehicle. Once repaired, though, my little Nissan Micra served me well. I took that little car everywhere – to Scotland, the French Alps, Spain. She was a trustworthy little vehicle that didn’t break down once in the seven years I drove her.

Despite my early difficulties in learning to drive, I loved driving. As a family we used to drive a lot. Every weekend we would pack up the Mobile Animal Clinic, and latterly the Space Cruiser, with my two sisters, our two golden retrievers and Humphrey, our African grey parrot.

In the summers, my sisters and I would be packed off to live with my paternal grandparents in Canada, where we experienced another approach to driving. My late grandmother, Aileen, was anything but your ordinary grandparent – agile and strong until the day she died, aged 100, she always stood out from the crowd, so it is probably no surprise that her car of choice was a sports car, a green Camaro with a V8 engine.

The ritual packing of the car would continue on the other side of the Atlantic, as Canadian dogs and cousins were all herded into the tiny sports car for the two-hour journey from the city of Toronto out to my grandparents’ little summer cottage on the shores of Lake Chemong.

Land Rovers did not cross my path again in any memorable way until 1999, when I took part in Castaway for the BBC. This programme was a year-long social experiment to see whether a group of urbanites could create a fully self-sufficient society from scratch. For this, we were marooned on an uninhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, in the Western Isles.

It was a remote, rugged place, and we were left there, isolated from the outside world. We had no internet, telephone nor television. It was just us and the windswept landscape of Taransay. The island had once been inhabited, but all that was left of its one-time occupation was a small farmhouse and an animal steading. Dotted around the island were remnants of its earlier history, in the form of black houses, their crumbling ruins a reminder of the crofters that had long ago worked the land.

The island topography was boggy and mountainous. There were no paths, tracks or roads, and crossing the island would involve a yomp through knee-high bogs and up the steep flanks of the hills that dominated the landscape. The absence of roads made the remains of the island’s sole vehicle even more remarkable and curious. Hidden near the animal steading that we had converted into the kitchen and communal area was the rusting body of a Land Rover Series II.

That Land Rover confused me more than almost every other aspect of island life. I couldn’t begin to fathom how such a vehicle would have been used, and why it was there. It wasn’t just the logistics of getting the vehicle onto the island that baffled me; rather, apart from the small area around which we built our settlement – which was about the size of two football pitches – I couldn’t imagine how the Land Rover would get across country. It seemed impossible that any vehicle, even a Land Rover, could make its way through this inhospitable geography.

The car had long since lost its engine, and its skeleton-like remains made a perfect place for the children to play and pretend they were driving somewhere. That island had a strange effect on all of us and even I used to sit in that dilapidated car and imagine I was on a journey, driving across a vast wilderness.

It was then and there that I resolved that I would one day get a Land Rover.

As our only communication with the outside world was via letter, and as the end of the year and the experiment loomed large, I wrote to my father to ask him to help me find a Land Rover for my return. When the end came it was a bittersweet moment. I longed to leave that island but I also worried about adapting to life back in the real world. For a year we had been isolated from the rest of the world, and suddenly, come 1 January 2001, having been stripped of our anonymity, we were about to be thrust back into civilisation – not to mention the public eye. It was a daunting prospect.

We were helicoptered off the island in a carefully choreographed live TV broadcast. I was last to leave. Tears streamed down my cheeks as we crossed that tiny body of turquoise water that separated us from the next main island of Harris.

Several dozen journalists and photographers had braved the Hebridean winter to gather on Horgabost beach ready for our arrival. It was the beginning of a new life in front of the media glare – and it scared me.

We transferred into coaches and began what seemed like a victory drive across the island to the Harris Hotel, where we would begin our decompression. I can’t begin to tell you how strange it was to be back in civilisation. A press conference was convened in the hotel’s dining room and we were thrust into the hungry grasp of the British press. It was quite a revelation. The questions. The spin. The stories. The money offers. The exclusives. Rival newspapers vied to outbid one another to get the scoop. We castaways became pawns in a game about which we knew very little. We didn’t understand the rules and we had very little help to pick our way through the minefield.

We were due to stay in the hotel for a few days to acclimatise and spend time with the show’s psychologist, but I found the whole experience overwhelming.

‘There’s something waiting for you in the car park,’ one of the show’s executive producers told me.

I escaped the claustrophobia and heat of the hotel and strode out into the wind and rain of the small gravel car park. There, tucked away in the corner, was the unmistakable shape of a blue Land Rover Defender. I pulled the handle of the unlocked door and climbed in. A set of keys had been ‘hidden’ beneath the sun visor. A smile enveloped my face. It was the Land Rover smile – more of which later.

I relaxed. It was as if all the fears and worries that had been brewing in that small hotel disappeared. I had my first Land Rover. It may seem strange, but I had no idea how it had got there, who had bought it, how much it cost or even if it really was mine. The world had become such a strange place that it never even occurred to me to ask.

While the rest of the castaways had been booked to fly back to civilisation from Stornoway, I had worried about flying back with my Labrador, Inca. She had only known freedom for a year; she hadn’t worn a collar nor been on a lead in that time and I couldn’t bear the thought of confining her to the hold of a plane in a cage, so driving seemed the natural solution to the problem.

My first night in a proper bed was not the luxury I had been anticipating. I found the central heating stifling and oppressive and the bed was far too soft – even apart from the fact that my mind was spinning and reeling. I was confused and, if I’m honest, I was scared, too.

I’m not sure what came over me or even why it happened, but I woke up in the middle of the night that first night – and left.

In retrospect it was completely out of character. I had planned to spend several more days with the show’s execs and the gathered journalists for interviews and photo shoots, but I was overwhelmed by the new situation I found myself in. So, quietly, I packed the Land Rover with my worldly possessions and Inca and placed the key in the ignition. The engine turned several times and then … spluttered to a stop. Several mysterious lights illuminated the dashboard. I tried again, willing the car to start, then finally the engine choked and spluttered to life. The whole car shuddered and vibrated. Inca sat in the passenger seat, her head lolling out of the window as we rolled out of town on the long journey home.

It was midwinter and sunrise was still hours away. I had been in plenty of Land Rovers through the years but this was the first time I had driven my own one. I felt a freedom that I had been deprived of for more than a year – a sense of liberty and sheer happiness at being able to explore, unfettered. That island had been like a prison, we had been confined by its watery limits, but here, now, aboard my mighty Land Rover, I felt invincible.

We drove past small shops selling newspapers that had my face on the front page as I drove up towards the ferry port of Stornoway. That had to be one of the more surreal experiences of my life.