Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

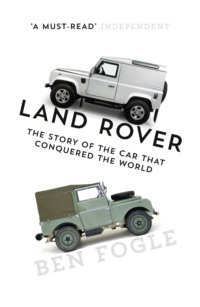

Kitabı oku: «Land Rover: The Story of the Car that Conquered the World», sayfa 2

Within hours of leaving the hotel, Inca, my trusty Land Rover and I were sailing away from the Hebrides and into the unknown of Scotland. I didn’t have a plan; all I had was my dog, a credit card and my Land Rover. Although I longed to see my friends and family, I wasn’t ready to return home just yet.

Aimlessly we drove through the Scottish Highlands. That Land Rover brought with it such a freedom. For more than twelve months I had been restricted to Taransay and now I had a wanderlust that was difficult to shake. Apart from the dizzying euphoria of movement, it was also a fear of stopping that overwhelmed me. If I were to stop I wasn’t really sure what would happen or if I would ever get moving again.

We drove until nightfall, when I pulled over to the side of the road and Inca and I curled up in the back of the Land Rover and went to sleep.

And so it was that I disappeared into the Scottish Highlands for a week. It seems strange now, but I don’t remember much about that time. I don’t recall where I went or even where I stayed. My Defender was like a ghost vehicle, winding its way through the mountains.

That Land Rover was my saviour. It offered so much more than just freedom; it also offered me opportunity and hope. And in many ways, this is the essence of the Land Rover spirit.

I kept that blue Land Rover for the best part of four years, but eventually the loan deal came to an end and I had to buy my own car. I’m not sure what came over me, but I bought a Jeep.

A Jeep? I hear you say. How did someone who had spent their life coveting a Land Rover end up with an American Jeep? It gets worse. It was a special Orvis edition pimped out with black leather seats and tinted windows. I am still genuinely puzzled by my decision to get that car. I wasn’t looking for it, it just sort of came into my life at a roundabout near Lord’s cricket ground.

You see, I am an experimenter. I like to experiment and test. I don’t like repeating myself. Perhaps it was a case of having spent four years bouncing and rattling around Britain in a Land Rover Defender that persuaded me to convert … to an American car.

To be fair, it was a cool car. Apart from the tinted windows – I hated those. Believe it or not, I didn’t notice those until after I had bought it. They didn’t stand out in the showroom and it wasn’t until I parked it outside my house and my sister commented on my new Gangsta credentials that I became aware of them.

I drove that Jeep for a year before I had a calling. I had been working on BBC’s Countryfile for several years when I rolled up to a Woad farm one day. ‘I thought you’d be more of a Land Rover man,’ smiled the farmer. It was like seeing the light. ‘But I am a Land Rover man,’ I replied, to the farmer’s confusion.

The Jeep was sold and I decided to do the unthinkable, what very few true Land Rover aficionados ever do: I bought a NEW one.

What was I thinking? We all know that buying a brand-new car off the factory line is like chucking money down the drain. The car depreciates as soon as the wheels leave the threshold of the showroom. I don’t think my parents had ever bought a new car. Not a brand-new one. The Fogles had always been rather sensible with money and we all knew that buying a brand-new car was a waste of money, but for some inexplicable reason I found myself in a Land Rover dealership on the A40 in West London putting in an order.

Buying the Land Rover was a big deal. Sure, I had been lucky enough to have cars of my own before, but this was different. I had worked hard for several years and I had saved up some cash. I have never been an extravagant spender (although my wife will probably disagree with that, but in truth it’s more that she is the spendthrift …!). All my life I had dreamed of walking into a showroom and picking out a Land Rover Defender, and here, finally, was my chance to do it. I can remember that day like it was yesterday; the excitement combined with a slight fear of the recklessness and extravagance of buying myself a new car.

The spec was really rather simple. The short wheelbase Defender 90 in silver. I wanted a silver Land Rover. Why silver? I don’t know. Car colour is a strange thing. I included some chequer body plating and three seats in the front. Now this is important – the three seats in the front is part of the Land Rover Defender’s DNA. If we look back to the early Series I and II they all had three seats in the front. It was part of the Land Rover design, but in the latter-day vehicles came the option to add a glove box in the middle.

I am always surprised by the number of Land Rovers that have gone for this configuration. I love the three seats in the front; it is the height of sociability. I remember peering into a McLaren once; the driver sits in the middle while the two passengers sit either side – the industry joke is that they are the seats for the wife and the mistress. With the Land Rover they are more likely to be for the wife and the calf. Next time you are in your car, have a look around at other vehicles and tell me how many have three passengers in the front. There are very few marques that do this – mostly vans. Have a look. Every van will inevitably have three grown men all sitting shoulder to shoulder. Sometimes there is a dog on one of the seats in place of a person, but you get my point.

There is something rather egalitarian about three seats in the front. It takes away the whole hierarchy thing for a start. What is it about the front seat? When I was a child it was like a throne. The front seat was the holy grail of seats and it was always allocated to a strict and unspoken rule of hierarchy, which was usually dictated by age. When Mum and Dad were both in the car there was never any question that they would sit in the front and we children, dogs and parrot would go in the back, but when it came to the school run and only one parent in the car, it became a war zone. ‘Shotgun!’ we would cry as we left the house and raced to the front door. Bickering and arguments would invariably ensue, followed by frosty sulking from the ‘backees’.

The three-seat configuration in the front gives all three passengers the same experience. It is much more inclusive, but of course there is a catch. Have you ever sat in the middle seat of a Land Rover?

A little like everything else about the Defender, it is not the most comfortable experience, indeed, some might call it uncomfortably intimate. The gear stick has to go somewhere, and in the case of the Defender it is located in front of the middle seat. While vans often have the same scenario, they are blessed with slightly more legroom and width. Not so the humble Land Rover, where the long gear stick is positioned between the middle passenger’s legs. Gears three and four are fine, but anything else requires full bodily contact with both gear stick and hand. It helps if you know and feel comfortable with the unfortunate passenger, but where’s the fun in that? I have lost count of the number of people I have taxied around in the middle seat of the Land Rover, their bodies contorted in a kind of twirl in order to avoid all physical contact.

Two months later, my Land Rover was ready. I couldn’t sleep the night before I collected her. I was surprised by my own emotions at the prospect of collecting a new car. She was a thing of beauty, with that unique factory smell that is impossible to replicate once it is lost. I can honestly say I didn’t stop smiling from the moment I stepped foot in that vehicle.

It still amazes me the power of a Land Rover to elicit emotion. Driving suddenly became fun again, and I don’t mean in a ‘pop to the shops as an excuse to get in your new car’ kind of way, but a ‘drive to Cornwall and back in a day’ kind of way. By this point I was working on a number of UK-based shows and I was covering more than 30,000 miles a year. My Silver Bullet went everywhere; although my growing green feelings erred on the side of train travel, I preferred the freedom and anonymity provided by my trusty steed.

Together we covered most of the British Isles. With my beloved Labrador Inca at my side we would drive the length and breadth of the UK to cover rural affairs for Countryfile. A great test of early girlfriends was to see if they could endure a Defender journey to Scotland and back – and I don’t just mean to the border, I mean right up to the Highlands and Islands. I’ll admit it, they were arduous journeys; the shaking and the noise left one feeling slightly frazzled. I must have done that trip a dozen times in a Defender. With nowhere to put a coffee cup or even a bottle of water and too much noise to listen to the radio, they weren’t the easiest journeys, but therein lies the sheer joy of Land Rover travel.

The beauty of the Land Rover lies partly in its characterful imperfections. No matter how noisy or bone-shockingly jarring a journey, I always smiled. She always left me feeling fulfilled. You see, a Land Rover really is so much more than just a vehicle – it becomes an extension of you. You begin to know and understand the nuances and quirks of your car. You can recognise every tiny feature of them. They become something so deeply personal that a criticism of your Land Rover is almost a criticism of you.

It is a well-known fact that the car of choice for the Chelsea mother is a 4×4. Indeed, the characterisation has led to its own term: the Chelsea Tractor. Drive past any school in London’s Kensington and Chelsea between 8am and 9am and you will see an ocean of 4×4s.

Now I will admit that living in Kensington and Chelsea and driving a ubiquitous 4×4 sometimes left me feeling a little guilty. ‘But I use it mostly in the country,’ I would invariably argue when confronted about it by one of my green-conscious friends. Indeed, the Silver Bullet probably saw more of the UK countryside than most Land Rovers, but she still retained an air of urban sophistication that meant she stood out just as much in the countryside. I would often deliberately drive up a couple of verges and through some muddy puddles before arriving at any farms or country fairs. I became conscious of her shiny metallic silver body that jarred against the standard-issue Land Rovers favoured by farmers.

All good things must come to an end, though, and in this case it really was self-inflicted.

Shortly before I rowed the Atlantic in 2005, I had started seeing a beautiful girl, Marina, who would later become my wife. In the early days of our relationship I decided it would be a good idea to drive her down to Devon in the Silver Bullet. It would be the early death knell for the Defender.

Soon after rowing the Atlantic I proposed to Marina. Our lives were amalgamated and Marina gently suggested that the Defender was no longer the most ‘suitable’ family car.

Now, this is far from unique. It is a time-honoured tradition that when a man gains a wife, he loses a car. Some of us fight for both, but one of them usually goes, and in my case I relented, but we wouldn’t lose the marque. We went for a Land Rover Discovery.

Before we took delivery of our black Discovery I had to decide what to do with the Silver Bullet. We didn’t need and couldn’t afford to keep two cars, so the Defender had to go.

I had let go of cars before, of course, but this was different. She really had become a part of me. Together we had been through so much. We had travelled the country together, she had towed my Atlantic rowing boat, we had been ‘papped’ together more times than I can recall (although I do remember the time we were papped on the phone together – me and the car, that is).

If I had had the means and wherewithal to keep her safe somewhere for the future, I would have done it in a flash, but she had to go.

I called some Land Rover dealerships to see if they wanted her and eventually settled on one just outside of Oxford. That final journey was like a funeral cortège. There was an overwhelming sadness as I found myself looking mournfully over her bonnet as we drove up the A40.

It may seem strange to mourn a car, and it had certainly never happened to me before, but there was a sense of finality when I handed over her keys. It was like closing a whole chapter of my life. This was the car I had dreamed of owning, and now that dream was over. It was like splitting up from a girl you still really like.

Now, don’t for a moment blame my wife. She was quite right. The Defender had served me well as a bachelor, but we needed something more suitable for the two of us. We were a partnership, after all, and it was a case of choosing a vehicle that met both our needs.

Marriage is all about compromise. Much is made about being ‘under the thumb’ and forced to make decisions you would never normally have made, but in our case it was about twinning our lives. I know of friends who had the same issues with their sports cars, who similarly mourned the loss of their beloved Porsche or Aston Martin on marriage.

Although it was time for the Defender to go, I resolved that one day I would once again drive the noisiest and most uncomfortable car.

The Discovery was a spaceship by compassion. It was like swapping from a Cessna aircraft to a Learjet. She was brimming with shiny lights, buttons and technology that the Defender could only ever dream of. But here’s the thing: the perfection obliterated the character and charm of her predecessor. I will admit that longer journeys took on a more comfortable edge, but I’ll be honest here, it never felt quite the same as getting into my old Defender. Without the quirks and the imperfections the Discovery became just a tiny bit bland. To use a male dating analogy, it would be like leaving an averagely pretty girl with a great personality for a supermodel. The supermodel is great for a while until you begin to miss character.

It is this that drives the world of the Land Rover aficionado. It is its spirit that we often talk about. The Defender is brimming with character and quirkiness. Each vehicle is different. Each one has its own tale to tell.

HISTORY OF THE LAND ROVER

PART I

The story of the Land Rover begins way back in the dark days of the Second World War. Although the Amsterdam Motor Show of April 1948 is regarded as the birthplace of the marque, it was actually conceived much earlier. The vehicle that started it all had a very long gestation period, brought about by fate – and the war. Look closely at the red-brick walls of the office block at Land Rover’s famous factory in Solihull, on the outskirts of Birmingham, and you can still see traces of the camouflage paint applied during the 1939–45 conflict. The idea behind this paint job was to confuse Luftwaffe bombers, and presumably it worked, because while nearby Coventry was flattened the Solihull factory survived intact.

Rover had been building cars in Coventry since 1901, but the war changed its fortunes. In 1940, after the Coventry factory was destroyed by the German Luftwaffe’s blanket bombing of that city, Rover continued production of aero engines for the war effort at a government shadow factory – a few miles away at Solihull. The company was so successful that after the war the factory looked for new, civilian projects to keep its staff employed.

Steel was required to rebuild a war-torn world, but it was in short supply. Like everything else in post-war Britain, this metal was strictly rationed. What the country desperately needed was earnings from exports; to get steel, companies had to export 75 per cent of what they manufactured. That was a tall order, even for a successful car manufacturer like Rover, which had earned a comfortable living by selling plush saloon cars to the middle classes on the domestic market in the pre-war years. Now, although new models were planned, its 1930s designs were outdated and didn’t appeal to British motorists, let alone overseas buyers. It seemed that Rover had little chance of persuading the government to allocate the all-important steel it needed. But there was, on the other hand, mountains of aluminium left over from the aircraft industry, if only somebody could find a use for it …

Although quirky four-wheel-drive cars had been in existence since the early years of the twentieth century, it was in the late 1930s, with the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Japan’s imperial ambitions, and when war looked inevitable, that a go-anywhere utility vehicle became a necessity. The Americans realised that they were eventually likely to get involved in the European conflict, so the US government invited tenders for the 4×4 military vehicle that would eventually become the Jeep (designed by the American Bantam Car Co and Willys-Overland, but eventually built by both the latter company and, under licence, Ford).

The Jeep played a major part in resolving the war in the Allies’ favour, and when peace was declared in 1945 there was no shortage of takers for the vehicles that had inevitably been left behind in Europe, now surplus to military requirements. These all-terrain vehicles were particularly popular with farmers – and gentleman-farmer Maurice Wilks was no exception.

In the overgrown graveyard of St Mary’s Church at Llanfair-yn-y-Cwmwd, on the Isle of Anglesey, North Wales, is the weathered gravestone of Maurice Wilks, which reads: ‘A much-loved, gentle, modest man whose sudden death robbed the Rover company of a chairman and Britain of the brilliant pioneer who was responsible for the world’s first gas turbine driven car.’

Like the man himself, the inscription is modest, for it fails to mention the invention for which he is best known – the Land Rover.

Wilks died in 1963, aged just 59. In his all-too-short life he also helped to develop Frank Whittle’s original jet engine, but he will forever be remembered for creating the motor car that took the world by storm. Nobody back in the 1940s, 50s and 60s could have predicted how the utilitarian little 4×4 would one day become the car of the stars. When Wilks died, even his family underestimated the importance of the Land Rover. They thought he’d be best remembered for his contribution to Rover’s ill-fated gas turbine car, which is why that got mentioned on his gravestone and the Land Rover didn’t.

Maurice, engineering director at the Rover car company, owned a rugged 250-acre coastal estate at Newborough, on the island of Anglesey, which was made more accessible thanks to his own ex-US Army Jeep. The truth was, he thoroughly enjoyed the experience of 4×4 off-road driving. Old home movies still in the possession of the Wilks family show him driving it at every opportunity. Whenever he was able to escape the hustle and bustle of the Rover factory for the wilderness of Anglesey, the man and his machine were seldom parted.

One day, his brother Spencer, Rover’s managing director, asked him what he would do when the battered warhorse eventually wore out. ‘Buy another one, I suppose – there isn’t anything else,’ was his fateful reply.

Legend has it that the Wilks brothers were relaxing on the beach at the time – at Red Wharf Bay in Anglesey, to be precise – and Maurice began drawing a picture of his ideal 4×4 in the sand. Unsurprisingly, it looked very much like his Jeep. It wasn’t long before the rough sketch became reality, though, for the brothers reckoned there was a definite niche for a civilian version of the Jeep, and they decided to build it at Solihull.

Again, circumstances played their part. With steel strictly rationed, Rover decided to create the new vehicle’s bodywork from Birmabright aluminium alloy panels. The steel box-section chassis was born of necessity, with strips of steel cast-offs hand-welded together to create a ladder frame. As well as being cheaper to install than a heavy press or expensive sheet steel, it also achieved the level of toughness appropriate for an off-road utility vehicle. Astonishingly, the same basic ladder-frame chassis was used throughout the production of the Series Land Rovers, as well as the Defenders, right up until the manufacture of the last cars in January 2016. The ladder-frame chassis was also the backbone of the first- and second-generation Range Rovers (1970–2002), Discovery 1 and 2 (1989–2003) and the various military specials and forward controls produced at Solihull.

The new 4×4 planned by the Wilks brothers also had great export potential. In 1947, British schoolchildren still toiled in classrooms in which a map of the world took pride of place on the wall, one that showed more than half of the land mass coloured pink – denoting countries that were either British colonies or former colonies (by then part of the British Commonwealth). The sun had not yet set on the British Empire and there were plenty of colonial outposts in the developing world where Rover’s projected new all-terrain vehicle would prove an invaluable mode of transport. So although the first Land Rover was designed with the British farmer in mind, its versatility meant that it would be a brilliant workhorse anywhere on the planet where the going was likely to get tough. (And it still is. For example, in the remote Cameron Highlands of Malaysia, extremely battered Land Rover Series Is are even today the main mode of transport in the tea plantations, including some very early 80-inch models, which would be worth a fortune as ‘garage finds’ in the UK!)

The introduction of the Land Rover marked a fresh start at the company’s new Solihull premises, and the enthusiasm of the management for the vehicle was such that it even axed its plans for its projected ‘mini’ car, the M1 (which had reached prototype stage by 1946), in favour of the newcomer.

The first Land Rover prototype was built in the summer of 1947. Its chassis came from a Willys Jeep, as did the axles, wheels and leaf-spring shackles. It is believed that other components, such as the springs, shock absorbers, bearings, brakes and brake drums, were also of Jeep origin, along with the transfer box and several transmission parts, including propshafts, universal joints and handbrake. The engine was an under-powered 1389cc unit from a Rover saloon. The car differed from the Jeep in that it had a more cramped driving position, because Rover wanted to provide the largest possible payload area in the back and so moved the driver’s seat forwards three inches to achieve it. Comfort was extremely rudimentary: just a plain cushion in the middle of the metal seat box, which also covered the fuel tank. With the export market in mind, the vehicle had a tractor-like, centrally-mounted steering wheel to save building separate left- and right-hand-drive models. Thus it became known as the Centre-Steer.

Today, the Centre-Steer prototype is the Holy Grail to many Land Rover enthusiasts. That’s because apparently no trace of it exists; although some very respected Land Rover experts are convinced it does. In fact, some believe several Centre-Steers are secreted away somewhere.

The official line is that this very first 1947 Land Rover was abandoned to rot in a shed somewhere in the Rover works at Solihull and was eventually thrown away during a spring-clean. It had certainly disappeared completely a few years later. Some say its remains were shovelled ignominiously into a skip and went for scrap. Others believe an employee with a better sense of history than his bosses succeeded in spiriting away the remains for preservation.

Either way, the Centre-Steer, cobbled together mainly out of Jeep parts, is actually a bit of a red herring when it comes to the genesis of the Land Rover that would eventually go into production. Rover’s engineers quickly realised that the Centre-Steer wasn’t a viable proposition and opted instead for the conventional wisdom of separate right- and left-hand-drive vehicles. Although the development engineers borrowed some ideas from the Jeep – notably the 80-inch wheelbase – the parts for the new vehicle were all designed and built by Rover. Work continued through 1947 and in February 1948 they began to build the first pilot prototypes. It had been decided that the new vehicle – by now christened the Land-Rover (note the hyphen between ‘Land’ and ‘Rover’, which wasn’t lost until a decade later) – would be launched at the Geneva Motor Show in early March, but it soon became clear that the prototypes wouldn’t be completed in time, so it was decided that it would launch at the Amsterdam Motor Show instead.

Thus it was, in the Dutch capital, on 30 April 1948, that the Land Rover legend was born. Two prototypes – left- and right-hand-drive variants – were on public display. One was a standard model, the other equipped by PTO (power take-off)-driven welding equipment, to demonstrate the versatility of the strange-looking little vehicle.

The initial 80-inch wheelbase Land Rovers that were sold to the general public remained very agricultural in every respect. Heaters were non-existent, as were passenger seats, door tops and roofs, but that hardly mattered because cabs and hard tops were yet to be introduced and Solihull’s new arrival was intended to be very much open plan, with the driver exposed to the elements. Nothing unusual there; contemporary tractors, combine harvesters and other farm machinery of that era didn’t have modern comfortable cabs either.

Nobody minded the Spartan comforts anyway once they had encountered the new vehicle’s amazing capabilities. They didn’t even bat an eyelid when the original purchase price of £450 was jacked up to £540 in October 1948. The first year’s production was 3048, but this more than doubled to 8000 the following year, doubling again to 16,000 in 1950. What had been seen as a stop-gap exercise, cobbled together from Rover car components and other bits copied from the original Jeep, was now a very important vehicle in its own right, and one that would eventually outsell – and indeed outlive – Rover cars. The company clearly had a success story on its hands.

Land Rover plodded on. There were developments aplenty in the following years, but they were evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Today, more than 60 years on, you can stand one of the last Defenders alongside the earliest Series I and there’s no mistaking the family resemblance.

The first prototypes were powered by a 1398cc engine, which developed a mere 48bhp. This, however, was deemed inadequate, so the production vehicles were equipped with the 1595cc side-valve unit that had been designed for the Rover P3 60 saloon car. Various drivetrain and axle changes along the way were also dictated by contemporary saloon variants until, in August 1951, the vehicle received the very welcome 1997cc overhead valve engine, which delivered a 26 per cent increase in torque at low engine speeds.

In 1953, the wheelbase was extended to 86 inches, and a long wheelbase version at 107 inches was also introduced. In 1956, these were further extended to 88 and 109 inches to accommodate the bigger 2052cc diesel engine, which became available for the first time a year later.

The very earliest Land Rovers were available in light green only. Legend has it that the company managed to secure a bulk purchase of war surplus paint used to decorate the interiors of RAF bombers, and it was only when that ran out that Land Rovers were sold in the familiar dark green (known as Bronze Green) now synonymous with the marque. It was some years before further colour options – blue and grey – became available.

Although the choice of paintwork was limited, the sky was the limit as far as other options went. The simple, bolt-together construction of the vehicle and its generous provision of power take-off points meant that it could be readily adapted for industrial as well as agricultural use. In fact, a fire-engine variant had been included among the original prototypes, proving that the company was on the ball from the start. Mobile compressors and welders were among the special vehicles available direct from Solihull, but like the 1948 coach-built Tickford Station Wagon, they were not a financial success. Also, many modified variations on the Land Rover theme were – and still are – produced by independent specialists. Today, these are mainly luxury, bespoke variants created by companies like Nene Overland (who produced my own distinctive set of wheels).

The Tickford Station Wagon, Land Rover’s first foray into comfortable transport, failed because of the eye-watering levels of purchase tax imposed by the government on luxury goods in the immediate post-war years. However, the company returned to the abandoned Station Wagon theme late in 1954 with a seven-seater on the short wheelbase 86-inch chassis, and accommodation (albeit rather cramped) for ten in the long wheelbase 107-inch version. Alloy-framed bodies replaced the expensive wooden frames of the earlier Tickford version and, although the long wheelbase model in particular looked for all the world as though it had been assembled from a Meccano set, both were an immediate and enduring success.

Enthusiasts love the rugged simplicity of the Series I. Its lack of creature comforts and austere lines give it an aesthetic purity unrivalled by any other motor vehicle, before or since. But it is also a brilliantly practical vehicle for travel in the most remote parts of the world, and, like many early Land Rovers, much revered and much sought-after.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.