Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Harold Wilson», sayfa 2

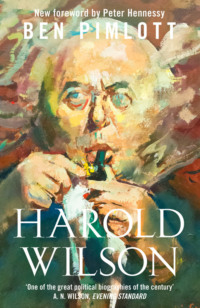

It is not surprising, therefore, that when he finally announced he was standing down, just days after his sixtieth birthday, he was worn out – if still chirpy in his pawkier moments – having sat almost continually on Labour’s front bench since the late summer of 1945. His longevity at or near the top of his party, his temperament, his gifts, his cockiness combined with social edginess – the sheer variety of Harolds he could put on display according to need or taste – made him the richest of characters for the biographer’s art. And in Pimlott on Wilson, subject and biographer were supremely well met.

Rereading his Harold Wilson serves only to remind us what a huge loss Ben Pimlott was to the historians’ trade and to political commentary. Tracing the Buchanite curves of contemporary British history as we travel them is so much harder without Ben. ‘What would Ben have made of this?’ is a thought that still crosses my mind when an event breaks or a political shift becomes apparent, as, for example, the weekend in September 2015 when Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour leadership race. But, above all, what would Ben Pimlott have made of the Wilson legacy in the centenary year of Harold’s birth? It is a matter of great regret – personal and professional – that this question must go unanswered.

Peter Hennessy, FBA,

Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History,

Queen Mary, University of London.

South Ronaldsay, Walthamstow and Westminster.

December–January 2015–16

Preface

In the old days, writing the life of a public figure was frequently part of a process of canonization. Only after the subject was respectably dead would it be attempted, and then by arrangement between the executors and a suitable admirer, with the implicit purpose of enhancing the reputation of the deceased. A customary part of the ritual was for the author to declare at the beginning of the book that the co-operation of the family had been provided unconditionally, and that no pressure had been exerted whatsoever. Such a work was known as the ‘official’ or ‘authorized’ biography.

This book is neither official nor authorized, but it would be untrue to say that I have not been under any pressure while writing it. Pressure – from Lord Wilson’s former supporters and opponents in politics, from Whitehall and Fleet Street confidants and critics, and from his personal friends and enemies – has been unremitting. At the same time, it has always been courteous, usually charming and often – unless I was very careful – beguiling. Indeed, as a way of getting to know and understand my subject, it has been invaluable, as much for the appreciation of the feelings which he and the politics of his time aroused, as for the details of the arguments that were put to me.

I have a great many debts. The first is to the Wilsons who have been unfailingly kind and helpful. In particular, I have greatly benefited from conversations with Lord and Lady Wilson, and Robin Wilson. I am also most grateful to them for family papers, photographs and other documents.

Several people have helped with the research. I would especially like to thank Anne Baker, who investigated a number of collections of private papers on my behalf with the greatest sensitivity and professional skill. I am also grateful to Andrew Thomas, who conducted interviews in Huddersfield and Huyton, and Gerard Daly, who examined Labour Party papers at the Labour Museum in Manchester. Among the many archivists and librarians who responded to my queries and were generous with their time, I should like to thank, in particular, Stephen Bird, formerly at the Labour Party Library in Walworth Road and now at the National Museum of Labour History; Dr Angela Raspin, at the British Library of Political and Economic Science; Helen Langley, at the Bodleian Library, Oxford; Christine Woodland, at the Modern Records Centre at Warwick University; Dr Correlli Barnett at Churchill College, Cambridge; Caroline Dalton at New College, D.A. Rees at Jesus College and Christine Ritchie at University College, Oxford; and Ruth Winstone, editor of the Tony Benn Diaries. I am grateful to the large number of people who helped me by correspondence or on the telephone. For sending me documentary material, I should like to thank Michael Crick, Francis Wheen, Sir Alec Cairncross, Lord Young of Dartington, Lord Jay, David Edgerton, Mervyn Jones and Ron Hayward. I am most grateful to Lord Jenkins for allowing me to see a manuscript copy of his autobiography, before it was published, and to Tony Benn, for letting me rummage around in his basement archive.

I am grateful to the following for permission to quote copyright material: Jonathan Cape (B. Pimlott (ed.), The Political Diary of Hugh Dalton; P.M. Williams (ed.), The Diary of Hugh Gaitskell), Hamish Hamilton Ltd (J. Morgan (ed.), The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister, 3 Vols.; Richard Crossman, The Backbench Diaries of Richard Crossman), David Higham Associates (Barbara Castle, The Castle Diaries, 2 Vols.), Hutchinson (Mary Wilson, New Poems; Tony Benn, Diaries), Michael Joseph (H. Wilson, Purpose in Politics, and Memoirs: the Making of a Prime Minister), Macmillan Publishers Ltd (Roy Jenkins, A Life at the Centre), and Manchester University Press (M. Dupree (ed.), Lancashire and Whitehall: The Diary of Raymond Streat). For the use of unpublished papers and documents I am grateful to Harold Ainley (Ainley papers), Tony Benn (Tony Benn papers), Bodleian Library (Attlee papers, Lord George-Brown papers, Goodhart papers, and Anthony Greenwood papers), British Library of Political and Economic Science (Beveridge papers, Dalton papers, and Shinwell papers), Lord Cledwyn (Cledwyn papers), John Cousins (Frank Cousins papers), Susan Crosland (Crosland papers), Anne Crossman (Crossman papers), Livia Gollancz (Victor Gollancz papers), the Gordon Walker family (Gordon-Walker papers), Lady Greenwood (Anthony Greenwood papers), Lord and Lady Kennet (Kennet papers), Labour Party Library (Labour Party archives), Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick (Maurice Edelman papers and Clive Jenkins papers), the Warden and Fellows of Nuffield College, Oxford (Cole papers, Fabian Society papers and Herbert Morrison papers), Hon. Francis Noel-Baker (Noel-Baker papers), National Museum of Labour History, Manchester (Parliamentary Labour Party papers), Frieda Warman-Brown (Lord George-Brown papers), Ben Whitaker (Ben Whitaker papers), the Wilson family (Wilson family papers).

I am extremely grateful to the following people, who have talked to me in connection with this book: Harold Ainley, Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, Tony Benn, Sir Kenneth Berrill, H.A.R. Binney, Lord Bottomley, Professor Arthur Brown, Sir Max Brown, Sir Alec Cairncross, Lord Callaghan, Bridget Cash, Baroness Castle, Lord Cledwyn, Brian Connell, John Cousins, Lord Cudlipp, Tam Dalyell, Lord Donoughue, Baroness Falkender, Peggy Field, Michael Foot, Paul Foot, John Freeman, Lord Glenamara, Geoffrey Goodman, Lord Goodman, Joe Haines, Lord Harris of Greenwich, the late Dame Judith Hart, Roy Hattersley, Ron Hayward, Lord Healey, Janet Hewlett-Davies, Lord Houghton, Lord Hunt of Tamworth, Henry James, Lord Jay, Lord Jenkins of Hillhead, the late Peter Jenkins, Jack Jones, Lady Kennet, Lord Kennet, Lord Kissin, David Leigh, Lord Lever, Sir Trevor Lloyd-Hughes, Lord Longford, Lord Lovell-Davies, David Marquand, Lord Marsh, Lord Mayhew, Lord Mellish, Ian Mikardo, Jane Mills, Sir Derek Mitchell, Sir John Morgan, Lord Murray, Sir Michael Palliser, Enoch Powell, Merlyn Rees, William Reid, Jo Richardson, George Ridley, Lord Rodgers, Andrew Roth, A.J. Ryan, Lord Scanlon, Lord Shawcross, Peter Shore, Professor Robert Steel, Sir Sigmund Sternburg, Sir Kenneth Stowe, Lord Thomson of Monifieth, Alan Watkins, Ben Whitaker, Sir Oliver Wright, Lord Wyatt of Weeford and Sir Philip Woodfield. I also interviewed a number of other people who prefer not to be named. Where it has not been possible to give the source of a quotation in the notes, I have used the words ‘Confidential interview’. I apologize for the frequency with which I have had to resort to this formula. Andrew Thomas interviewed Harold Ainley in Huddersfield, and Jim Keight, Ron Longworth and Phil MacCarthy in the North-West. I would like to thank them as well.

I am deeply grateful to Professor David Marquand who has read the whole of my manuscript, and to Dr Hugh Davies who has read the sections which touch on economic questions. Their careful and detailed comments, based on wide experience and expert knowledge, have been an invaluable help. More than is usually the case, however, it needs to be stressed that the opinions expressed in this book are those of the author alone. I am greatly indebted to Anne-Marie Rule, who typed the manuscript with her usual speed, care and professional skill, who I always have in mind as my first audience, and whose many kindnesses are part of the background to my work. I am grateful for secretarial and other much valued assistance, at various stages of the project, to Audrey Coppard, Harriet Lodge, Susan Proctor, Kim Vernon, Terry Mayer and Joanne Winning. I would also like to thank my colleagues and students at Birkbeck, who have provided an intellectual atmosphere, at once stimulating and relaxed, that creates the ideal conditions for research.

I wish to express my gratitude to Stuart Proffitt, the ideal publisher, at HarperCollins; to Rebecca Wilson, my hawk-eyed, perfectionist and tireless editor, who has been a joy to work with; and to Melanie Haselden for imaginative picture research. I would also like to thank Giles Gordon, my friend, literary agent and therapeutic counsellor. It was Giles who – over a very pleasant lunch in 1988 – was pretty much responsible for setting the whole thing in motion.

Other friends have helped in ways too numerous to mention. I should like, however, to express my special gratitude to David and Linda Valentine, and to Susannah York, who – with immense kindness – lent me their respective houses on the Ionian island of Paxos, where a large part of this book was written.

Most of all I wish to thank my wife, Jean Seaton, my cleverest and most inspiring critic, about whom I do not have words to say enough. Her insight and her passion for ideas have been vital to this book, as to everything I write.

Ben Pimlott

Gower Street

London WC1

September 1992

Part One

1

ROOTS

When James Harold Wilson was born in Cowersley, near Huddersfield, on 11 March 1916, his father Herbert was as happy and prosperous as he was ever to be in the course of a fitful working life. The cause of Herbert’s good fortune was the war. Nineteen months of conflict had turned Huddersfield into a boom town, putting money into the pockets of those employed by the nation’s most vital industry, the production of high explosives for use on the Western Front. Before Harold had reached the age of conscious memory, the illusion of wealth had been destroyed, never to return, by the Armistice. Harold’s youth was to be dominated by the consequences of this private set-back and by a defiant, purposeful, family hope that, through virtuous endeavour, the future might restore a lost sense of well-being.

Behind the endeavour, and the feeling of loss, was a sense of family tradition. Both Herbert and his wife Ethel had a pride in their heritage, as in their skills and their religion, which – they believed – set them apart. When, in 1963, Harold Wilson poured scorn on Sir Alec Douglas-Home as a ‘fourteenth Earl’, the Tory Prime Minister mildly pointed out that, if you came to think about it, his opponent was the fourteenth Mr Wilson. It was one of Sir Alec’s better jokes. But it was also unintentionally appropriate. The Wilsons, though humble, were a deeply rooted clan.

They came originally from the lands surrounding the Abbey of Rievaulx, in the North Riding of Yorkshire. The connection was of very long standing: through parish records a line of descent can be traced from a fourteenth-century Thomas Wilson, villein of the Abbey lands.1 The link with the locality remained close until the late nineteenth century, and was still an active part of family lore in Harold’s childhood: as a twelve-year-old, Harold submitted an essay on ‘Rievaulx Abbey’ to a children’s magazine. Herbert knew the house near to the Abbey where his forebears had lived. In his later years in Cornwall, he called his new bungalow ‘Rievaulx’,2 and Harold included the name in his title when he became a peer.

‘When Alexander Lord Home was created the first Earl of Home and Lord Dunglass, in 1605’, researchers into Harold’s ancestry have pointed out, ‘there had already been seven or eight Wilsons in direct line of succession at Rievaulx.’3 Through many generations, Wilsons seemed to celebrate the antiquity of their family in the naming of their children. Herbert and Ethel called their son Harold, after Ethel’s brother Harold Seddon, a politician in Australia. But Harold’s first name, James, belonged to the Wilsons, starting with James Wilson, a weaver who farmed family lands at Helmsley, near Rievaulx, and died in 1613.4 Thereafter James was the most frequently used forename for eldest or inheriting sons. Thus James the weaver begat William, whose lineal descendants were Thomas, William, William, James, John, James, James, John, James, James, John, James, before James Herbert, father to James Harold, whose first son, born in 1943, was named Robin James, and grew up knowing that there had been James Wilsons for hundreds of years. Indeed, Harold was not just the twentieth or so Mr Wilson, but the ninth James Wilson in the direct line since the accession of the Stuarts.

Wilsons did not stray more than a few miles from the Abbey for several centuries. The religious upheaval of the Civil War in the mid-seventeenth century brought a conversion from Anglicanism to Nonconformity, an affiliation which the family retained and retains. Otherwise there were few disturbances to the pattern of a smallholding, yeoman existence, in which meagre rewards from farming were eked out by an income from minor, locally useful, crafts. Not until the nineteenth century did the importance of agriculture as a means of livelihood decline for the Wilson family.

It was Harold’s great-grandfather John, born in 1817, who first loosened the historic bond with the Abbey garth. John started work as a farmer and village shoemaker, taking over from his father and grandfather the tenancy of a farm in the manor of Rievaulx and Helmsley, and living a style of life that had altered little for the Wilsons since the Reformation. John married Esther Cole, a farmer’s daughter from the next parish of Old Byland, close to Rievaulx. (During Harold’s childhood, Herbert took his family to visit Old Byland, where they stayed with Cole cousins who ran the local inn.) In the harsh economic climate of the 1840s, however, it became difficult to make an adequate living from the traditional family occupations. At the same time, the loss of trade that had thrown thousands out of work and onto the parish in many rural areas of England, created new opportunities of a securely salaried kind. John Wilson had the good fortune, and resourcefulness, to take one of them.

In 1850, Helmsley Workhouse was in need of a new Master and Relieving Officer (for granting ‘outdoor’ relief). The incumbent had been forced to resign after an enquiry into his drunkenness and debts. At first, John Wilson agreed to take his place for a fortnight, pending the choice of a successor. The election which followed was taken with the utmost seriousness by the Helmsley Parish Guardians. An advertisement in the local newspaper produced fourteen husband-and-wife teams for the joint posts of Master and Matron of the Workhouse, which took both male and female paupers. References were submitted, all fourteen were interviewed and six were shortlisted. The ensuing contest, by the exhaustive ballot system, was tense. Though Wilson was well known locally, and had the advantage of being Master pro tem, there was strong opposition to his appointment. After the first vote, he was running in third place. After the second, with four candidates still in the race, Wilson tied with a Mr Jackson at 14 each. In the run-off, Wilson and Jackson tied again. Fortunately, Wilson was still owed two weeks’ salary by the previous Master, for the period in which he had replaced him. This tipped the scales. The minutes of the meeting record that the Chairman gave his casting vote in favour of Wilson, and declared John Wilson and Esther his wife duly elected.5 It was scarcely an elevated appointment. The accommodation was so restricted that the new Master and Matron were permitted to take only one of their children in with them. Yet, it was a decisive turning-point.

John was a man of restless ambition. He continued to farm the lands at Helmsley, and the appointment was partly a way of supplementing a small income. But there was more to it than that, as his later career shows. John not only became the first Helmsley Wilson to take a public office: he was also the first of his line with a vision of a future that extended beyond the parish. In 1853 he and his wife applied for and obtained posts as Master and Matron at the York Union Workhouse, Huntingdon Road, York, at salaries of £40 and £20 each, with the prospect of an increase to £50 and £30 after a year. This was appreciably more than the £55 in total which they had received at Helmsley, though it involved moving away from the small community, and the lands, which Wilsons had farmed for centuries.

The Wilsons’ desire to better themselves did not stop there. Two years after arriving at York Union, they felt secure enough to bargain their joint salaries up from £80 to £100. With this they were prepared to rest content, turning the York Union into a family undertaking, in which one of their daughters was also involved as Assistant Matron. They retired in 1879 when John Wilson became seriously ill. He died two years later. Esther survived him, and lived in York until her own death in 1895. Both she and her husband had received a pension in recognition of twenty-six years at the Workhouse in which they had ‘most efficiently, successfully and to the satisfaction of this Union discharged their duties …’6

John and Esther’s son James, Harold’s grandfather, was the last of Harold’s forebears to be born at Rievaulx. James finally severed the ancient link, becoming the first to give up the husbandry of the lands around the Abbey ruins. He moved to Manchester in 1860, at the age of seventeen, apprenticed as a draper, and later worked as a warehouse salesman. He was also the first to wed out of the locality. It was a significant match: his marriage to Eliza Thewlis was a socially aspirant one. Eliza’s father, Titus Thewlis, was a Huddersfield cotton-warp manufacturer who employed 104 workers (including, as was later revealed, some sweated child labour). This might have meant a generous dowry. Unfortunately for the Wilsons, however, Eliza was one of eight children.7 The James Wilsons themselves had five children and were never well off.

Though the Thewlis connection brought little money, it provided a new influence, with a vital impact on the next generation: an interest in political activity. ‘Why are you in politics?’ Harold was asked in an interview when he became Labour Leader. ‘Because politics are in me, as far back as I can remember,’ he replied. ‘Farther than that: they were in my family for generations before me …’8 Harold was not the fourteenth political member of his family, but he was far from being the first. According to Wilson legend, Grandfather James had been an ardent radical who celebrated the 1906 Liberal landslide by instructing the Sunday school of which he was superintendent to sing the hymn, ‘Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea/Jehovah hath triumphed, his people are free.’9

There were Labour, as well as Liberal, elements in the family history. Herbert Wilson’s brother Jack (Harold’s uncle), who later set up the Association of Teachers in Technical Institutions and eventually became HM Inspector of Technical Colleges, had an early career as an Independent Labour Party campaigner. In the elections of 1895 and 1900, he had acted as agent to Keir Hardie, the ILP’s founder. The most notable politician on Herbert’s side of the family, however, was Eliza Wilson’s brother, Herbert Thewlis, a Manchester alderman who became Liberal Lord Mayor of the city. Harold’s great-uncle Herbert happened to be constituency president in northwest Manchester, when Winston Churchill fought a by-election there in 1908, caused by the need to recontest the seat (in accordance with current practice) following his appointment as President of the Board of Trade. Alderman Thewlis assisted as agent, and Herbert Wilson, Harold’s father, helped as his deputy. It was a famous battle rather than a glorious one. Churchill lost the seat, and had to find another in Dundee. Nevertheless, the Churchill link was a source of gratification in the Wilson family, as the fame of the rising young politician grew, and Harold was regaled with stories about it as a child.

Herbert Wilson’s main period of political involvement had occurred before the Churchill contest. Herbert’s story was one of promise denied. Born at Chorlton-upon-Medlock, Lancashire, on 12 December 1882, he had attended local schools, and had been considered an able pupil, remaining in full-time education until he was sixteen – an unusual occurrence for all but the professional classes. There was talk of university, but not the money to turn talk into reality. Instead, he trained at Manchester Technical College and entered the dyestuffs industry in Manchester. Though he acquired skills and qualifications as an industrial chemist, it was an uncertain trade. In the early years of the century fluctuations in demand and mounting competition brought periods of unemployment. It was during these that Herbert became involved in political campaigning.10

In 1906, at the age of twenty-three, Herbert Wilson married Ethel Seddon, a few months his senior, at the Congregational Church in Openshaw, Lancashire. Ethel also had political connections, though of a different kind. Her father, William Seddon, was a railway clerk, and she had a railway ancestry on both sides of her family. The working-class element in Harold’s recent background, though already a couple of generations distant, was more Seddon than Wilson: Ethel’s two grandfathers had been a coalman and a mechanic on the railways, and her grandmothers had been the daughters of an ostler and a labourer.11

Where Wilsons had been individualists, Seddons were collectivists. William Seddon was an ardent supporter of trade unionism, and so was his son Harold, the apple of the family’s eye. Ethel’s brother, of whom she was immensely proud, had emigrated to the Kalgoorlie goldfields in Western Australia, worked on the construction of the transcontinental railway, and made his political fortune through the Australian trade union movement.12 As tales of Harold Seddon’s prosperity filtered back in letters, other Seddons joined him, including his father William, who got a job with the government railways.13 During Harold Wilson’s childhood, Ethel’s thoughts were always partly with the Seddon relatives, to whom she was devoted, and who, in her imagination, inhabited a world of sunshine and plenty.

Such links with the world of public affairs – actively political uncles on both sides – added to the Wilsons’ sense of difference. Yet there was nothing grand about the connections, and there was no wealth. Social definitions are risky, because they mean different things in different generations. The Wilsons, however, are easy enough to place: they were typically, and impeccably, northern lower-middle-class. Their stratum was quite different from that of Harold’s later opponent, and Oxford contemporary, Edward Heath, whose manual working-class roots are indisputable.14 But Herbert and Ethel did not belong, either, to the world of provincial doctors, lawyers and headteachers. In modern jargon, they were neither C2S nor ABs, but CIS.

On 12 March 1909, a year after the Churchill excitement, Ethel gave birth to her first child, Marjorie. Herbert’s political diversions now ceased, and for seven years the Wilsons’ attention was taken up by their cheerful, intelligent, rotund only daughter. Perhaps it was the unpredictable nature of the dyestuffs industry which deterred them from enlarging their family. At any rate, in 1912 the vagaries of the trade uprooted them from Manchester – the first of a series of nomadic moves that punctuated their lives for the next thirty years. Herbert’s search for suitable employment took him to the Colne Valley, closer to Wilson family shrines. Here he obtained a job with the firm of John W. Leitch and Co. in Milnsbridge, later moving to the rival establishment of L. B. Holliday and Co. Milnsbridge was one mile west of the boundary of Huddersfield. Herbert rented 4 Warneford Road, Cowersley, a small terraced house not far from the Leitch works and adequate for the family’s needs: with three bedrooms, a sitting-room, dining-room, and lavatory and bathroom combined, as well as small gardens back and front.15

The chemical industry was already fast expanding in Huddersfield and the outlying towns. Established early in the nineteenth century, local manufacturing had been built up partly by Read Holliday (founder of L. B. Holliday) and partly by Dan Dawson (whose successors were Leitch of Milnsbridge), who developed the use of coal tar. By 1900 Huddersfield was proudly claiming to be the nation’s chief centre for the production of coal-tar products, intermediates and dyestuffs. There were a score of factories servicing the woollen and worsted mills, providing a series of complex processes which went into the dyeing of cloth, including ‘scouring, tentering, drying, milling, blowing, raising, cropping, pressing and cutting’.16

Huddersfield, like other industrial towns, felt the disturbing impact of German rivalry in the years before the First World War. What seemed a threat to the area in peacetime, however, became a golden opportunity as soon as the fighting began. Dyestuffs were needed for the textile and paper industries. With German supplies no longer available, British production had to increase. ‘It was not until after War had broken out with Germany’, a Huddersfield handbook observed, and the humiliating fact of our too great dependence upon that country for many valuable, nay, vital products, became unpleasantly manifest that the general British public, and even Government circles, began to realize how essential to the life of a great nation was a well-organized and highly developed coal tar industry.’ There was also another, fortuitous aspect: namely, that most high explosives used in modern warfare, in particular picric acid, trinitrotoluene (TNT) and trinitrophenylmethylmitramine (tetryl), were derivatives of coal tar, whose use and properties were familiar to the dyestuffs industry. Thus, Herbert’s first employer in Milnsbridge, Leitch and Co. (which described itself as a firm of ‘Aniline Dye Manufacturers and Makers of Intermediate Products, and Nitro Compounds for Explosives’) claimed to have been the first makers of TNT in Britain, having started to manufacture the substance as early as 1902.

H. H. Asquith, Liberal Prime Minister in 1914, was a Huddersfield man. By leading his government into the Great War, he transformed the economy of his home town. As the importance of artillery bombardment during the great battles in Flanders and northern France grew, so the demand for high-explosive shells became insatiable. Production in Huddersfield increased tenfold, with John W. Leitch and Co. a major beneficiary. By the summer of 1915, when Harold was conceived, both the firm and the town were booming (the word seems particularly appropriate) as never before.17

Herbert Wilson was in charge of the explosives department of Leitch and Co. Before the war, this was a job of limited importance and modest pay. The starting wage of £2.10s. per week provided for the Wilsons’ needs, but permitted few luxuries. The sudden boost in production changed all that, and Herbert’s value to the firm, and his salary, rapidly increased. By 1916 Herbert was earning £260 per annum, plus an annual profit bonus of £100. Herbert and Ethel responded to their good fortune in two ways. They decided to have another child, partly in the hope (as it was said) of a son to carry on the family name, for Herbert’s married brother only had daughters. They also decided to move to a better neighbourhood. A year after Harold’s birth, as the big guns before the Somme threw into the German trenches the best that Huddersfield and Milnsbridge had to offer, Herbert, Ethel, Marjorie and Harold moved to 40 Western Road, Milnsbridge, a more salubrious address and a larger, semidetached house with a substantial garden. Such was the Wilsons’ new-found affluence that Herbert became an owner-occupier, paying £440 for the house – £220 from savings, the rest on a mortgage.18

For Ethel and Marjorie, it seemed like a gift from heaven. Marjorie had a large room of her own. There was a cellar, where Ethel did the laundry, and a spacious attic, which in due course became Harold’s lair, with ample room to set up his Hornby train. It was, as a school-friend says, a middle-class dwelling in a middle-class area.19 The peak of Herbert’s success, however, had not yet been reached. Eighteen months after the move, and doubtless anticipating the changed pattern of production after wartime needs had ceased, Herbert accepted a job as works chemist in charge of the dyes department at L. B. Holliday and Co., the nation’s biggest supplier of dyestuffs, at a salary of £425 per annum.20 Prices had risen during the war, but even allowing for inflation, the mortgage and the baby, the Wilsons were now very much better off than they had been in 1914. At the age of thirty-six, Herbert had reached a plateau from which there would be no further ascent. His move to Holliday and Co. coincided almost exactly with the ending of the war. A contraction of the chemical industry followed, long before the onset of the national depression – placing a pall of uncertainty over all who worked in it. Yet there was no immediate cause for concern. Though demand for explosives fell sharply, it was some time before the dyestuffs industry faced pre-war levels of competition.