Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Harold Wilson», sayfa 5

When Wilson became Prime Minister, much was made of his lowly origins. Yet he was by no means the first non-public school boy to reach No. 10 Downing Street. Five twentieth-century predecessors had not attended a famous school, and two – Lloyd George and Ramsay MacDonald – had not been to university either. But one peculiarity did mark him out. He was an English provincial.

Amongst other prime ministers not of upper- or upper-middle-class origin, only one – H. H. Asquith – came from an English town, coincidentally the same as Wilson’s. But Asquith received only his early education in the North. At the age of eleven he was sent to board at the City of London School, and to acquire the speech and habits of mind of a Southerner. Asquith went to Balliol, was called to the Bar and represented Scottish seats for the Gladstonian Liberal Party: he became an honorary gentleman. Wilson, by contrast, wore his roots like a badge, continuing to speak in a Yorkshire accent which made some people feel, by a contorted logic, that the experience of Oxford and Whitehall ought to have ironed out the regional element, and the fact that it had not done so reflected a kind of phoniness. The truth was that, for all his other conceits, Wilson was the least seducible of politicians in social terms, remaining imperturbably close in his tastes and values – as in his marriage – to the world in which he had grown up. It was a bourgeois world, of teachers, clerks and nurses: an existence which drew its strength from patterns of work, orderliness, routine, respectability, thrift, religion, family, local pride, regard for education and for qualifications. It was a world from which luxury, party-going, fashion, drink, sexual licence, art and culture were largely absent.

The Prime Minister whose social background Wilson’s most resembles is not Edward Heath or John Major, still less Jim Calla-ghan (all Southerners from differing tribes), but Margaret Thatcher. In key respects, the early lives of the two leaders were remarkably similar. Both were brought up in or near middling English industrial towns. Both came from disciplined, Church-based families and had parents who valued learning, while having little formal education themselves. Both were given more favourable attention than an elder sister, their only sibling, who, in each case, entered a worthwhile career of a lesser-professional kind (Margaret’s sister became a physiotherapist, Harold’s a primary school teacher).

Both were Nonconformists. The Robertses were Methodists. In his biography of Mrs Thatcher, Hugo Young writes: ‘[Alfred Roberts] was by nature a cautious, thrifty fellow, who had inherited an unquestioning admiration for certain Victorian values: hard work, self-help, rigorous budgeting and a firm belief in the immorality of extravagance.’ Margaret spent every Sunday of her childhood walking to and from the Methodist church in the centre of Grantham. We have already discussed the role played by Milnsbridge Baptist Church in the Wilsons’ family life. Harold’s own memoirs speak of ‘regular chapel-going and a sense of community’ and his parents’ ‘capacity for protracted hard work …’33

Both future premiers followed the same pattern in their education. After attending a council primary school, both won places at grant-aided grammar schools, their fees paid by county scholarships. There they worked and played with a dedication brought from their homes. By coincidence, Margaret’s subject, the highly practical one of chemistry, was also Herbert’s and Marjorie’s. Their levels of attainments were similar. Both passed into Oxford (a glittering prize for any grammar school pupil), but each did so by a narrow margin. Neither was regarded as brilliant at school. For both, university was a critical launching-pad.

The early political training of the two future leaders also contains a parallel. In both families, political achievement was considered the acme of success. ‘Politics infused the atmosphere in which she was reared,’ writes Young. ‘… A political family handed down the tradition of political commitment from one generation to the next.’34 Harold’s comment that politics had been ‘in my family for generations before me’, will be recalled. Harold, like Margaret, had an alderman in his family, Alderman Thewlis of Manchester, in addition to an Australian state legislator. Both Alfred and Herbert began in the Liberal Party, the characteristic political home of provincial Nonconformity, before moving in contrary directions when the Liberals fell apart in the 1920s.

The Wilsons were better educated than the Robertses and, some of the time, slightly richer. In Western Road they lived in a semidetached house with an indoor lavatory: Alderman Roberts lived over his grocer’s shop, with the lavatory in the yard. The Wilsons took more holidays, and there was the unusual adventure of the Australian trip, which Margaret’s family could scarcely have contemplated. Moreover, the psychological roles of husband and wife in the two families were to some extent the reverse of each other: Ethel, a teacher, was the strongest character in the Wilson household, whereas Margaret’s mother (as portrayed by Young) was colourless and downtrodden. Herbert lacked the steel of Alfred, a local dignitary.

Yet the similarity of the early years of the two overlapping party leaders – inhabitants of No. 10 Downing Street for nineteen years between them – in class, wealth, standard of living, interests, habits, attainment and upbringing, is such that if they had grown up at the same time in the same town they would almost certainly have known each other. There were probably several Margaret Hilda Robertses at Royds Hall, and many must have played tennis at the Brotherton’s club. It is noteworthy that one of Gladys’s cousins, Tom Baldwin, kept a grocer’s shop – like Margaret’s father.35

There were, however, two differences which greatly influenced the outcome. First, Harold and Margaret were not contemporaries. Margaret was nine and a half years Harold’s junior, and from that gap huge differences in outlook arose. Second, Alfred Roberts was a self-employed businessman, while Herbert was an employee.

Harold spent his adolescence and early manhood during the worst years of the depression. The collapse of world markets, and the failure or inability of governments to soften the impact on British manufacturing industry, came close to breaking Herbert’s spirit and destroying his career. Harold’s family was uprooted, and his education interrupted, by the effects of unemployment. By contrast, Margaret entered her teens and became politically conscious only as the depression came to an end. Alfred Roberts suffered during the hard times, but never badly. Where Harold’s youthful experience was of financial uncertainty caused by factors outside the family’s control, Margaret’s memory was of a solid security, the product, as she believed, of her father’s efforts and prudence.

After his illness, Harold continued to thrive at Royds Hall, while his father looked for work. But the atmosphere at home was sometimes close to despair. ‘The adjustment, not only of the wage- or salary-earner and his wife, but also of the children in a house struck by unemployment, is hard to describe,’ Wilson later recalled, ‘… I shall never really know how the family survived … Our food became more simple, although my mother always managed to keep me adequately fed … I concentrated with ever more determination on my schooling.’36 This was a state of affairs which Margaret never had to face in fully employed, Second World War Grantham.

Politicians like to emphasize their own childhood hardships, and Harold certainly made full use of his father’s periods of joblessness as a credential (just as Mrs Thatcher made use of her father’s corner shop and outside privy). Yet the fact of Herbert’s unemployment was real and so was the typical pattern of humiliation, self-recrimination, loss of professional dignity, and fear for the future which accompanied it. For Harold, the atmosphere at home was a powerful motivator, with Herbert cursing his lack of qualifications and transferring his own frustrated hopes onto his talented son. At Oxford, Harold took a professional interest in the trade cycle and the demand for labour. Later, as a politician, the prevention of unemployment became a primary aim. Unlike some of his Conservative opponents, who regarded joblessness as a form of weakness and saw the remedy in individual initiative, Harold always believed that state intervention was a necessity.

There was also a personal legacy. Herbert had imbued in his son a determination that, whatever happened, he would not end up at the mercy of his employers. The fear of sudden dismissal and exclusion stayed with Harold throughout his life, and his political career cannot be understood without seeing it as a central thread.

3

JESUS

In Oxford terms, the small college of Jesus was a backwater, which did not attract the ablest pupils from the most prestigious schools. Harold was told before he went up that it was ‘despised in Oxford’.1 Even Wirral Grammar School regarded it as second best. Its strongest traditional link was with Wales, though there were also many boys like Harold – especially among award-winners – who came from the North.2 Expectations among Jesus men were appropriately modest. Many became clergymen, schoolmasters or provincial lecturers. The ablest joined the Civil Service (the Home, not the Diplomatic), though the number of such entrants was barely more than a trickle, and averaged only one per annum in the inter-war years.3 The college’s best-known pre-war alumnus was the legendary T. E. Lawrence, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. Wilson is the only inter-war Jesus student to have achieved a general fame.

The unpretentiousness of Jesus made it relatively easy for the product of a provincial grammar school, and a relatively humble home, to adjust to the life of a tradition-bound university. It also meant that Wilson did not automatically rub shoulders with Oxford’s undergraduate élite. In this respect, his experience was different from that of some others who became Labour politicians after the Second World War, for whom Oxford was an entry-ticket to the governing class, if they were not members of it already. Hugh Gaitskell, Douglas Jay, Richard Crossman (all at New College), Frank Pakenham, Patrick Gordon Walker, Christopher Mayhew (at Christ Church), Denis Healey and Roy Jenkins (at Balliol) shared staircases and ate dinners from their very first term with well-connected, well-off young men who already had a confident view of their own place in the world. Harold did not find himself in such society and did not seek it. Throughout his days as an undergraduate, he was singularly indifferent to its activities.

Instead, he remained contentedly part of the other Oxford: the Oxford treated contemptuously by Evelyn Waugh in Decline and Fall and ignored completely in Brideshead Revisited. There are very few novels about Harold’s Oxford. Perhaps there should be more. Harold’s friends, however, did not end up writing novels. The other Oxford was dedicated to essays, marks, exams, chapel-going, sport and college societies at which learned papers were read and discussed. It was the Oxford of the overwhelming majority of undergraduates, not just at Jesus but in most other colleges as well. Harold differed from fellow members of this Oxford only in the ferocity of his determination to do well academically, and the remarkable extent of his success.

Harold’s letters home to his family, of which many survive from his first two years, provide a fascinating glimpse of the preoccupations of his early manhood years. They are not dramatic: what is noteworthy about them is how little they contain that is unusual, or might not have been written by hundreds of contemporaries who disappeared, after graduation, into anonymous staff rooms and parsonages. They reveal a highly conventional young man deeply absorbed in the formal experiences of university life. They show him stirred, sometimes movingly, by the intellectual ambitions, and casual presumption, of Oxford, and the opportunities the university provided for him to stretch his own capacities. They do not indicate any need or desire to stray beyond the bounds of officially approved learning.

What is going on in a young man’s head and what he tells his parents need not, of course, be the same thing: but there is no guile in his writing, much of which has a child-like quality. The letters deal mainly with wants, and how he is coping. They are about money – how much he has, how much he needs, how much things cost, and how he is making ends meet, often down to the last penny. They are about food and other provisions, to be purchased at Wirral rather than Oxford prices, to supplement meagre college rations; about tutors, lectures, societies, sport, his own unquenchable thirst for parental letters; and they are about Gladys. They are, by turns, warm, generous, demanding, winsome, boastful, witty, self-possessed. Though they are sometimes lonely, they are never anxious. They are forever looking ahead, planning moves in Harold’s own life, and organizing his parents to do things on his behalf, in the confident knowledge that they will comply. They are uncomplicated and loving. They present Harold as, already, a man content with who he is, where he comes from, and the upward direction in which he is heading, fighting battles on his own, with no need for backing other than the support he takes for granted from his family.

At first he was homesick. Unlike Gladys, with her experience of boarding-school, Harold had never lived away from his parents, except during his illnesses and at Scout camp. His early letters – lengthy and poignant, stressing the lack of home comforts – are full of characteristic symptoms. The contents of Harold’s laundry feature prominently: it had been agreed that he would send this back to Bromborough to save money. ‘I think that for the first fortnight’, he wrote on arrival, ‘I’ll just send my collars, hankies, vests, pants and socks.’4 He explained: ‘The reason there are so many hankies is that I have a bad cold.’5 Another letter suggested: ‘It might pay to send butter (it is very dear here) next week with washing, also two oranges.’6 To Marjorie he wrote: ‘Will you please send me a 6d. meat pie? I’ll send you the cash in my next letter.’ Was he all right, were the other chaps OK? asked his sister. He was happy, he replied. ‘That’s the answer to I of your questions,’ and to the other, ‘Yes, very decent set. No snobbery.’7 He had been placed in a first-floor room with a young Welsh Foundation Scholar, A. H. J. Thomas of Tenby. ‘He’s an exceptionally nice fellow & we seem to have similar tastes’, wrote Harold, ‘– both keen on running, neither on smoking or drinking, and have similar views on food, etc.’8 To illustrate the satisfactoriness of the Wilson–Thomas set-up, Harold drew a careful sketch-map of their joint room, showing its furnishings, and with a numbered key.

In search of company and familiar surroundings, Harold responded to an invitation to join the University Congregational Society, and got to know Dr Nathaniel Micklem, Principal of Mansfield, the Congregationalist Theological College. He also took an interest in the evangelical Oxford Group, which had many Nonconformist members. ‘Am enjoying the Group, it’s the only thing I’ve seen more than skin-deep,’ he wrote at the end of October, having had little luck with the political clubs.9 Both the Group, which offered secular as well as religious discussions, and Mansfield, became focal points. He often attended Sunday morning services in Mansfield Chapel, as well as evensong at Jesus. Later on, he sometimes accompanied a friend to Sunday evening concerts in Balliol chapel to hear the undergraduate Edward Heath (whom he did not yet meet) play the organ.10

Voluntary chapel-going, beyond what his own college required, became a reassuring part of his weekly routine. ‘There was a deeply religious element in his make-up which influenced much of his political thinking in later years,’ considers Eric Sharpe, a friend and contemporary at Jesus who attended services with him and later became a Baptist minister.11 Harold made much the same claim. ‘I have religious beliefs, yes’, he told an interviewer in 1963, ‘and they have very much affected my political views.’12 Mary does not quite agree. ‘Religion was part of his tradition,’ she says. ‘He never questioned it, but he did not think much about wider religious questions. When he did, he believed that people should translate Christianity into good works.’13 Labour colleagues, mainly atheist or agnostic, viewed Harold’s piety with cynicism. Set against his cat-like manoeuvrings at Westminster, it looked like humbug. Nevertheless, religious worship was part of the mould which formed him, his political outlook, and his idiom.

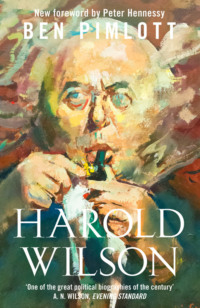

Harold’s sketch-map of his room at Jesus College, and its location.

At Oxford, religion and politics were often mixed. He used to go to a Congregationalist discussion group called the Dale Society on Sunday afternoons, to hear speakers who examined the link between faith and action. He frequently intervened. ‘He spoke with clarity and force,’ recalls another Jesus contemporary, Professor Robert Steel, who matriculated also as an exhibitioner in the same year. ‘He could put a case in a very persuasive manner, and unless you felt strongly you accepted what he said.’ One popular topic at the Dale Society was the colonies – in modern terms the Third World, a topic in which Harold took a special interest. ‘If someone gave a talk on the race problem, the chances were he would go to it,’ says Steel.14 He took an active interest in college discussion societies, becoming president of a couple of them. The college magazine records that in 1936 he addressed the Henry Vaughan Society in Jesus on ‘The Last Depression and the Next’ and caused offence to a former president of the society by referring to ‘“mugs” on the Stock Exchange’.15

Harold’s greatest solace was work. As a history undergraduate, he had to take prelims at the end of his first term, based on set books which included works in medieval Latin, and an economics textbook, Public Finance, by a former LSE lecturer called Hugh Dalton. Though the pass standard was not high, the quantity of material was large. ‘I doubt if I have worked so hard in my life,’ he said later.16 He was an early riser. Steel used sometimes to meet him in the bath house before breakfast – he would be conscious of Harold’s presence because his friend would sing the same songs repeatedly, at the top of his voice. He also used to see him regularly at dinner, where they sat together at the exhibitioners’ table. ‘Harold used to study a great deal, and then have a glass of beer,’ recalls Steel. ‘We all knew that he coped very well with essay writing and that he read voraciously.’17

Apart from the occasional beer, there was little time for anything else, except sport. At school he had been a keen long-distance runner. At Oxford he played football in the college second team, and tennis, even in winter. But athletics was his real passion. He ran on the Iffley Road track most afternoons. ‘He had an obsession about physical fitness,’ says Sharpe.18 He was a half-miler, though he sometimes ran longer distances as well. One such occasion, described in a letter, occurred in his second term. ‘I’ve some very good news,’ he wrote to his parents:

Just after breakfast this morning (Saturday) the cross-country captain came in & asked me to run for the Varsity Second Team v. Reading A. C. (I tried to send you a p.c. so you would know Saturday night, but couldn’t catch the post).

Well I ran: I started badly & after 2 miles was 14th out of a field of 16. After we had topped Shotover Hill, I got my second wind & moved a lot better. I caught up 7 places in the last mile – & finished 7th (the third Oxford man home…)…

After that we were taken in a motor coach to the city & had tea in a very posh restaurant – all of us on one table in a private room: the captains made speeches etc. I felt very thrilled about it all. So I’ve represented the Varsity. If I could only get my cross-country really well up, I might get my half-blue next year.

… Still feeling very thrilled; hope you’re also duly thrilled.19

Active politics – the precocious dream of his adolescence – had a lower priority. Nevertheless, the interest was still there. In his first week, he joined the League of Nations Union, and was approached by the Secretary of the University Labour Club, ‘a very decent fellow from Wallasey’. ‘I think I shall join the Lab. Club’, he wrote home, ‘– the sub’s only 2/6. I shan’t go to many meetings, just to those addressed by G. D. H. Cole and Stafford Cripps I think – both this term.’ He joined the Oxford Union on similar grounds, ‘partly on account of debates, hearing important men – Cabinet Ministers etc.’, but more because of the library.20

He made extensive use of the Union to take out books and as a place to work, and attended debates without taking part in them. The Labour Club, however, was a bitter disappointment. His first experience of it put him off. It struck him, he wrote home after attending a meeting a few weeks after going up, ‘as very petty: squabbling about tiffs with other sections of the labour party instead of getting down to something concrete’.21 Many years later, as a well-known politician, he elaborated on this point, maintaining that he ‘could not stomach all those Marxist public school products rambling on about the exploited workers and the need for a socialist revolution’.22 This became his standard excuse for not having taken part in Labour politics as a student. It was also a way of indicating to people who equated Bevanism with Communism that he had never belonged to the fellow-travelling left wing, while giving a side-swipe at the Labour Party’s upper-middle-class intellectuals, many of whom had started on the Left before moving rightwards.

The obvious explanation for Harold’s lack of political involvement in his first term was that he was not sufficiently interested and, with an exam a few weeks away, he had too much to do. These points are made in a very early, pencil-written note home, which accompanied his first laundry parcel, before he had yet attended a single Labour meeting. ‘Cole is speaking at the Labour Club to-night but I don’t think I’ll go,’ he wrote. ‘I’ll wait till next term for that sort of thing.’ He added a sentence which indicated the first call on his attention, after work: ‘I’ve been running twice at Iffley Road – nice track.’23 Yet the reason he gave later is also convincing. For his arrival at Oxford happened to coincide with a moment in undergraduate politics when the student Left was as febrile, and as out of touch with reality, as it ever became in the course of a heady decade. The Labour Club in 1934 was the crucible of fashion. But fashion was something to which Harold, sometimes to the irritation or scorn of contemporaries, was unusually immune.

‘In recent months there have been unmistakable signs of an increase of political consciousness amongst the undergraduates of Oxford and Cambridge,’ one observer noted at the beginning of 1934, before Harold went up, adding that political activity had been ‘largely confined to socialists and, to an increasing degree, to communists.’24 By the time of Harold’s arrival, a fertile generation of left-wing undergraduates that had included Barbara Betts (later Castle), Anthony Greenwood, Richard Crossman, Patrick Gordon Walker and Michael Stewart – all future members of Harold’s Cabinets – was just ending. But the memory of them was fresh. ‘Consciousness’ was the vogue word. ‘Oxford was very, very politically conscious,’ recalls a friend of Barbara Betts.25 An important raiser of consciousness, and prophet of Oxford socialism, was G. D. H. Cole, an ascetic thinker whose First World War semi-syndicalist ideas had given way to a Fabian, pragmatic approach, though still with a Utopian goal. In 1930–1, Cole had gathered together a group of young disciples at Oxford which included Hugh Gaitskell, a WEA lecturer who had recently graduated from New College, to help set up two closely linked ginger groups or (as they would now be called) think tanks: the New Fabian Research Bureau and the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (which in October 1932 merged with the pro-Labour rump of the old ILP to form the left-wing Socialist League). There was much excitement over these developments in Oxford, where Cole’s admirers were encouraged to see themselves as the vanguard of Labour’s intellectual revival.

The MacDonald and Snowden betrayal, and the subsequent Labour collapse, acted as the spur. ‘While the events of autumn 1931 lost thousands of voters to the Labour Party in the country as a whole’, recorded two young chroniclers of the University’s politics a couple of years later, ‘in Oxford the rapid growth of socialist opinion suffered no comparable set-back.’ By the end of 1932 the Labour Club had attained a record membership of almost five hundred, and a ‘Socialist Dons’ Luncheon Club’, with thirty or forty members, was meeting weekly.26 The upward curve of left-wing activity continued in 1933 and 1934, the year of Harold’s arrival at Jesus. As interest increased, however, so the orientation changed, away from the careful programme-building of Cole, and towards the international vistas and harsh dogmatism of King Street and Moscow.

Communism began to be important in Oxford in 1931, when some undergraduates set up the October Club, a Communist-front body whose secret aim was to control as much of Oxford left-wing politics as possible. Within a year, the Club had a membership of 300, which included many people who were also in the Labour Club. When Harold went up in 1934, the October Club was at the peak of its recruiting zeal: one of Harold’s first decisions on taking up residence was to reject the overtures of an Octobrist who wanted him to join, explaining politely but firmly (as Harold related in a letter to Marjorie), ‘I didn’t want to.’27 Many others, however, became members of both the October and the Labour Clubs, either gullibly or sympathizing with the Communist point of view.

When Harold went to his first meeting of the Labour Club, the ‘Marxist public school products’ were about to stage a Communist takeover. Anthony Blunt, the KGB spy, later described how Marxism ‘hit Cambridge’ (by which he meant smart, sophisticated Cambridge) early in 1934.28 It hit Oxford a few months later. An important development for Marxists in both universities, as for Communists generally, was an alteration in Moscow’s international tactics, occasioned by Soviet concern about a resurgent Germany. The switch was not sudden: rather, there was a gradual change of approach away from the former ‘Class against Class’ line to the ‘Popular Front’, officially adopted by the Comintern at its Seventh Congress in 1935. The new line meant that democratic socialists were no longer to be denounced as social fascists; instead they were to be coaxed into alliance in a ‘popular front’, or coalition of left-wing forces. This was the theory: in practice, it meant that Communists were supposed to use every wile to subvert Labour Party citadels. In Oxford it gave zealous Octobrists a motive for a fifth-column assault on the Labour Club, in the name of a ‘popular front’.

The merger between the two Clubs was brought about by secret Communists early in Harold’s undergraduate career. Christopher (now Lord) Mayhew, Harold’s exact Oxford contemporary and a Labour activist in the University, remembers that some two hundred Communist undergraduates ‘dominated the fifteen hundred members of the Labour Club, using techniques that are familiar enough today but frequently caught us off our guard then’. It emerged that, for some time, Labour Club elections had been rigged by the simple expedient of conducting a ballot and then falsifying the results.29 Philip Toynbee – who made his name as a public school runaway before going up to Oxford and becoming Communist President of the Union – later boasted that every member of the Labour Club executive was a secret member of the Communist Party, except Mayhew who ‘never seemed to have grasped that all the others were’.30 Mayhew’s own claim is that, though duped for a time, he eventually saw through the ploy.31 Later, Mayhew led a breakaway Democratic Socialist Group – anticipating the Social Democrat split in the national Labour Party half a century later, in which some of the same people were involved, taking the same sides. Mayhew himself was the first Labour MP to cross over to the Liberals, while the leader of the 1981 Gang of Four, Roy Jenkins, had also been an Oxford Democratic Socialist. Denis Healey, on the other hand, stayed with Labour in 1981 as he had done in the late 1930s when, although a Communist, he had been elected Chairman of the Labour Club.

It was fun to be a Communist at Oxford in the 1930s, if you had the money and the leisure to sustain the lifestyle. Toynbee claimed that when membership of the Party reached its peak in 1937 of 200 or so (eighty per cent of whom were undercover members, passing for ordinary supporters of other parties) it was far from being a public school preserve: at least half its membership came from grammar schools.32 This was not, however, the more vociferous half, and there was some justice in the comment of a critic in Isis, the undergraduate magazine, who wrote after a notable Union debate that if the Communists wanted to take power, ‘they really should insist that everyone is sent to a public school’. Oxford socialism had become an exclusive society with its own code and rituals. Labour Club members called each other ‘comrade’, not just in meetings, but also in private conversation. Isis noted that any serious office-hunter at the Union had to denounce capitalism. A socialist who wore the customary evening dress for debates needed to ensure that his bowtie was a ready-made one, ‘to show his contempt for bourgeois prejudices’.33