Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Fools and Mortals»

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2017

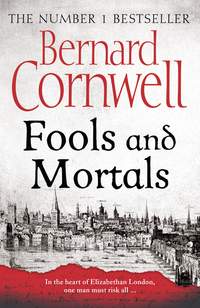

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018. Cover images © World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo (London panorama); Ian Dagnall/Alamy Stock Photo (Shakespeare’s last will and testament).

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Part One illustration: 17th century view of London © Private Collection/Bridgeman Images

Part Two illustration: Elizabethan theatre scene © Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy

Part Three illustration: The Globe Theatre from ‘Old and New London’ by Edward Walford © Montagu Images/Alamy

Part Four illustration: Scene from an Elizabethan playhouse © Chronicle/Alamy

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007504145

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2018 ISBN: 9780007504138

Version: 2018-10-17

Dedication

Fools and Mortals

is dedicated, with affection,

to all the actors, actresses, directors,

musicians and technicians of the

Monomoy Theatre

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part One: Excellent Men

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Part Two: Reason and Love

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Part Three: Things Base and Vile

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Four: A Sweet Comedy

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Epilogue

Historical Note

About the Author

Keep Reading …

Also by Bernard Cornwell

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication)

About the Publisher

Map

PUCK: Lord, what fools these mortals be!

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Act III, Scene 2, line 115

HIPPOLYTA: This is the silliest stuff that ever I heard.

THESEUS: The best in this kind are but shadows; and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them.

HIPPOLYTA: It must be your imagination then, and not theirs.

THESEUS: If we imagine no worse of them than they of themselves, they may pass for excellent men.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Act V, Scene 1, lines 207ff

PART ONE

EXCELLENT MEN

ONE

I DIED JUST after the clock in the passageway struck nine.

There are those who claim that Her Majesty, Elizabeth, by the grace of God, Queen of England, France, and of Ireland, will not allow clocks to strike the hour in her palaces. Time is not allowed to pass for her. She has defeated time. But that clock struck. I remember it.

I counted the bells. Nine. Then my killer struck.

And I died.

My brother says there is only one way to tell a story. ‘Begin,’ he says in his irritatingly pedantic manner, ‘at the beginning. Where else?’

I see I have started a little too late, so we shall go back to five minutes before nine, and begin again.

Imagine, if you will, a woman. She is no longer young, nor is she old. She is tall, and, I am constantly told, strikingly handsome. On the night of her death she is wearing a gown made from the darkest blue velvet, embroidered with a mass of silver stars, each star studded with a pearl. Panels of watered silk, pale lavender in colour, billow through the open-fronted skirt as she moves. The same expensive silk lines her sleeves, the lavender showing through slits cut into the star-studded velvet. The skirt brushes the floor, hiding her delicate slippers, which are cut from an antique tapestry. Such slippers were uncomfortable, as tapestry shoes always are unless lined with linen or, better, satin. She wears a ruff, high at the back and starched stiff, and above it her striking face is framed by raven-black hair, which is pinned into elaborate coils and rolls, all looped with strings of pearls to match the necklace that hangs down her bodice. A coronet of silver, again decorated with pearls, shows her high rank. Her pale face shimmers with a strange, almost unearthly glow, reflecting the light from the flames of a myriad candles, while her eyes are darkened, and her lips reddened. She has a straight back, and throws her hips forward and pushes her shoulders back so that her silk-clad bosom, which is neither too large nor vanishingly small, draws the eye. She draws many eyes that night for she is, as I am frequently told, a hauntingly beautiful woman.

The beautiful woman is in the company of two men and a younger woman, one of whom is her killer, though she does not yet know it. The younger woman is dressed every bit as beautifully as the older, if anything her bodice and skirt are even more expensive, bright with pale silks and precious stones. She has fair hair piled high, and a face of innocent loveliness, though that is deceptive, for she is pleading for the older woman’s imprisonment and disfigurement. She is the older woman’s rival in love, and, being younger and no less beautiful, she will win this confrontation. The two men listen, amused, as the younger woman insults her rival, and then watch as she picks up a heavy iron stand that holds four candles. She dances, pretending that the iron stand is a man. The candles flicker and smoke, but none goes out. The girl dances gracefully, puts the stand down, and gives one of the men a brazen look. ‘If thou would’st know me,’ she says archly, ‘then thou would’st know my grievance.’

‘Know you?’ the older woman intervenes, ‘oh, thou art known!’ It is a witty retort, clearly spoken, though the older woman’s voice is somewhat hoarse and breathy.

‘Thy grievance, lady,’ the shorter of the two men says, ‘is my duty.’ He draws a dagger. For a candle-flickering pause it seems he is about to plunge the blade into the younger woman, but then he turns and strikes at the older. The clock, a mechanical marvel that must be in the corridor just outside the hall, has started striking, and I count the bells.

The onlookers gasp.

The dagger slides between the older woman’s waist and her right arm. She gasps too. Then she staggers. In her left hand, hidden from the shocked onlookers, is a very small knife that she uses to pierce a pig’s bladder concealed in a simple linen pouch hanging by woven silver ropes from her belt. The belt is pretty, fashioned from cream-coloured kidskin with diamond-shaped panels of scarlet cloth on which small pearls glitter. When pricked, the pouch releases a gush of sheep’s blood.

‘I am slain,’ she cries, ‘alas! I am slain!’ I did not write the line, so I am not responsible for the older woman stating what must already have been obvious. The younger woman screams, not in shock, but in exultation.

The older woman staggers some more, turning now so that the onlookers can see the blood. If we had not been in a palace, then we would not have used the sheep’s blood, because the velvet gown was too rich and expensive, but for Elizabeth, for whom time does not exist, we must spend. So we spend. The blood soaks the velvet gown, hardly showing because the cloth is so dark, but plenty of blood stains the lavender silk, and spatters the canvas that has been spread across the Turkey carpets. The woman now sways, cries again, falls to her knees, and, with another exclamation, dies. In case anyone thinks she is merely fainting, she calls out two last despairing words, ‘I die!’ And then she dies.

The clock has just struck nine times.

The killer takes the coronet from the corpse’s hair, and, with elaborate courtesy, presents it to the younger woman. He then seizes the dead woman’s hands, and, with unnecessary force, drags her from view. ‘Her body here we’ll leave,’ he says loudly, grunting with the effort of pulling the corpse, ‘to moulder and to time’s eternity.’ He hides the woman behind a tall screen, which mostly hides a door at the back of the stage. The screen is decorated with embroidered panels showing entwined red and white roses springing from two leafy vines.

‘A pox on you,’ the dead woman says softly.

‘Piss on your bollocks,’ her killer whispers, and goes back to where the audience is motionless and silent, shocked by the sudden death of such dark beauty.

I was the older woman.

The room where I have just died is lit by countless candles, but behind the screen it is shadowed dark as death. I crawled to the half open door and wriggled through into the antechamber, taking care not to disturb the door itself, the top of which can be seen above the rosy screen.

‘Gawd help us, Richard,’ Jean said to me, speaking softly. She brushed a hand down my beautiful skirt that was stained with sheep’s blood. ‘What a mess!’

‘Will it wash out?’ I asked, standing.

‘It might,’ she said dubiously, ‘but it will never be the same again, will it? Pity that.’ Jean is a good woman, a widow, and our seamstress. ‘Here, let me wet the silk.’ She went to fetch a jug of water and a cloth.

A dozen men and boys lounged at the room’s edges. Alan was sitting close to two candles and silently mouthing words he was reading from a long piece of paper, while George Bryan and Will Kemp were playing cards, using one of our tiring boxes as a table. Kemp grinned. ‘One day he’ll stick that knife right through your ribs,’ he said to me, then grimaced, pretending to die. ‘He’d like that. So would I.’

‘A pox on you too,’ I said.

‘You should be nice to him,’ Jean said to me as she began dabbing ineffectually at the sheep’s blood. ‘Your brother, I mean,’ she went on. I said nothing, just stood there as she tried to clean the silk. I was half listening to the players in the great chamber where the Queen sits on her throne.

This was the fifth time I had played for the Queen; twice in Greenwich, twice at Richmond, and now at Whitehall, and folk are forever asking what is she like, and I usually make up an answer because she is impossible to see or describe. Most of the candles were at the players’ end of the hall, and Elizabeth, by the grace of God, Queen of England, France, and Ireland, sat beneath a rich red canopy that shadowed her, but even in the shadow I could see her face white as a gull, unmoving, stern, beneath red hair piled high and crowned with silver or gold. She sat still as a statue except when she laughed. Her face, so white, looked disapproving, but it was evident she enjoyed the plays, and the courtiers watched her as much as they watched us, looking for clues as to whether they should enjoy us or not.

Her bosom was white like her face, and I knew she was wearing ceruse, a paste that makes the skin white and smooth. She wore her dresses low like a young girl enticing men with a hint of pale breasts, though God knows she was old. She did not look old, and she glowed in her expensive fabrics, which were studded with jewels that caught the candlelight. So old, so still, so pale, so royal. We dared not look at her, because to catch her eye would break the illusion we offered her, but I would snatch a glimpse when I could, seeing her paste-white face above the perfumed crowd, who sat on the lower seats.

‘I might have to sew new silk into the skirt,’ Jean said, still talking softly, then she shivered as a gust of wind blew rain against the antechamber’s high windows. ‘Nasty night to be out,’ she said, ‘raining like the devil’s piss, it is.’

‘How long before this piece of shit ends?’ Will Kemp asked.

‘Fifteen minutes,’ Alan said without looking up from the paper he was reading.

Simon Willoughby came through the door from the great hall. He was playing the younger woman, my rival, and he was grinning. He is a pretty boy, just sixteen years old, and he tossed the coronet to Jean then twirled around so that his bright pale skirts flared outwards. ‘We were good tonight!’ he said happily.

‘You’re always good, Simon,’ Will Kemp said fondly.

‘Not so loud, Simon, not so loud,’ Alan cautioned with a smile.

‘Where are you going?’ Jean demanded of me. I had gone to the door leading to the courtyard.

‘I need a piss.’

‘Don’t let the velvet get wet,’ she hissed. ‘Here, take this!’ She brought me a heavy cloak and draped it around my shoulders.

I went out into the yard where rain seethed on the cobbles, and I stood under the shelter of a wooden arcade that ran like a cheap cloister about the courtyard’s edge. I shivered. Winter was coming. There was a deeply arched gateway on the yard’s far side where two torches guttered feebly. Something dark twitched in the arcade’s corner. A rat perhaps, or one of the cats that lived in the palace. A pox on the palace, I thought, and a pox on Her Majesty, for whom time does not exist. She likes her plays to begin in the middle of the afternoon, but the visit of an ambassador had delayed this performance, and it would be a wet, dark and cold journey home.

‘I thought you needed to piss?’ Simon Willoughby had followed me into the courtyard.

‘I just wanted some fresh air.’

‘It was hot in there,’ he said, then hauled up his pretty skirts and began to piss into the rain, ‘but we were good, weren’t we?’ I said nothing. ‘Did you see the Queen?’ he asked. ‘She was watching me!’ Again I said nothing because there was nothing to say. Of course the Queen had been watching him. She had watched all of us. She had summoned us! ‘Did you see me dance with that tall candle-stand?’ Simon asked.

‘I did,’ I said curtly, then strolled away from him, following the cloister-like arcade about the courtyard’s edge. I knew he wanted me to praise him because young Simon Willoughby needs praise like a whore needs silver, but there could never be enough compliments to satisfy him. Other than that he is a decent enough boy, a good actor and, with his long blond hair, pretty enough to make men sigh when he plays a girl.

‘It was my idea,’ he called after me, ‘to pretend the candle-stand was a man!’

I ignored him.

‘It was good, wasn’t it?’ he asked plaintively.

I was at the courtyard’s far side now, deep in the shadows. No hint of the flames guttering in the archway could reach me here. There was a door to my right, barely visible, and I opened it cautiously. Whatever room lay beyond was in even deeper darkness. I sensed it was a small room, but did not enter, just listened, hearing nothing above the wind’s bluster and the rain’s ceaseless beat. I was hoping to find something to steal, something I could sell, something small and easily hidden. In Greenwich Palace I had found a small bag of seed pearls which must have been dropped and lay half obscured beneath a tapestry-covered stool in a passageway, and I had hidden the small bag beneath my skirts, then sold the pearls to an apothecary who ground them small and used them to cure insanity, or so he said. He paid me far less than they were worth because he knew they were stolen, but I still made more money in that one day than I usually make in a month.

‘Richard?’ Simon Willoughby called. I kept silent. The dark room smelled foul, as if it had been used to store horse feed that had turned rotten. I reckoned there would be nothing to steal and so closed the door.

‘Richard?’ Simon called again. I remained silent and did not move, knowing I would be invisible in my dark cloak. I liked Simon well enough, but I was in no mood to tell him over and over how good he had been.

Then a door on the courtyard’s far side opened, letting a wash of lantern-light into the rain-soaked courtyard. At first I thought it would be one of the players, come to let us know we were needed, but instead it was a man I had never seen before. He was young and he was rich. It is easy to tell the rich from their clothes, and this man was dressed in a doublet of shining yellow silk, slashed with blue. His hose was yellow, his high boots brown and polished. He wore a sword. His hat was blue with a long feather, and there was gold at his throat and more gold on his belt, but what stood out most was his long hair, so palely blond that it was almost white. I wondered if it was a wig. ‘Simon?’ the young man called.

Simon Willoughby answered with a nervous giggle.

‘Are you alone?’

‘I think so, my lord.’ Simon had heard me open and close a door, and must have thought I had gone into the palace. Then the far door closed, plunging the newcomer into shadow. I was utterly still, just another shadow within a shadow. The young man walked towards Simon, and the guttering torches in the gate arch threw just enough light for me to see that his boots had heels like those on women’s shoes. He was short and wanted to look taller. ‘Richard was here,’ I heard Simon say, ‘but he’s gone. I think he’s gone.’

The man said nothing, just pushed Simon against the wall and kissed him. I saw him haul up Simon’s skirts and I held my breath. The two were pressed together.

There was nothing surprising in this, except that his lordship, whoever he was, had not waited till the play’s ending to find Simon Willoughby. Every time we had played at one of the Queen’s palaces, the lordlings had come to the tiring room, and I had watched Simon disappear with one or other of them, which explained why Simon Willoughby always appeared to have money. I had none, which is why I needed to thieve.

‘Oh yes,’ I heard Simon say, ‘my lord!’

I crept nearer. My tapestry slippers were silent on the stones. The wind fretted loud around the palace roofs, and the rain, already relentless, increased in vehemence to drown whatever the two said. There was just enough light from the becketed torches to see Simon’s head bent back, his mouth open, and, still curious, I crept still nearer. ‘My lord!’ Simon cried, almost in pain.

His lordship chuckled and stepped back, releasing Simon’s skirts. ‘My little whore,’ he said, though not in an unkind voice. I could see that even with the women’s heels on his boots he was no taller than Simon, who is a full head shorter than me. ‘I don’t want you tonight,’ his lordship said, ‘but do your duty, little Simon, do your duty, and you shall live in my household.’ He said something more, though I could not hear it because the wind gusted to drive hard rain on the cloister’s roof, then his lordship leaned forward, kissed Simon’s cheek, and went back to the tiring room.

I stayed still. Simon was leaning against the wall, gasping. ‘So who is the dwarf?’ I asked.

‘Richard!’ he sounded both scared and alarmed. ‘Is that you?’

‘Of course it’s me. Who is his lordship?’

‘Just a friend,’ he said, then he was saved from answering any more questions because the antechamber door opened again, and Will Kemp leaned out. ‘You two whores, come,’ he snarled. ‘You’re needed! It’s the ending.’

My brother was evidently speaking the epilogue. I knew he had composed it specially, draping it onto the play’s end like ribbons on the tail of a harvest-home horse, and doubtless it smothered the Queen with compliments.

‘Come!’ Will Kemp snapped again, and we both hurried back inside.

When we are at the playhouse, we end every performance with a jig. Even the tragedies end with a jig. We dance, and Will Kemp clowns, and the boys playing the girls squeal. Will scatters insults and makes bawdy jokes, the audience roars, and the tragedy is forgotten, but when we play for Her Majesty, we neither dance nor clown. We make no jokes about pricks and buttocks, instead we line like supplicants at the edge of the stage and bow respectfully to show that, though we might have pretended to be kings and queens, to be dukes and duchesses, and even gods and goddesses, we know our humble place. We are mere players, and as far beneath the palace audience as hell’s goblins are beneath heaven’s bright angels. And so, that night, we made obeisance, and the audience, because the Queen had nodded her approval, rewarded us with applause. I am certain half of them had hated the play, but they took their cue from Her Majesty, and applauded politely. The Queen just stared at us imperiously, her bone-white face unreadable, and then she stood, the courtiers fell silent, we all bowed again, and she was gone.

And so our play was over.

‘We shall meet at the Theatre,’ my brother announced when, at last, we were all back in the antechamber. He clapped his hands to get everyone’s attention because he knew he needed to speak swiftly before some of the lords and ladies from the audience came into the room. ‘We need everyone who has a part in Comedy, and in Hester. No one else need come.’

‘Musicians too?’ someone asked.

‘Musicians too, at the Theatre, tomorrow morning, early.’

Someone groaned. ‘How early?’

‘Nine of the clock,’ my brother said.

More groaning. ‘Will we be playing The Dead Man’s Fortune tomorrow?’ one of the hired men asked.

‘Don’t be an arsehole,’ Will Kemp answered instead of my brother, ‘how can we?’

The urgency and the scorn were both caused by a sickness that had afflicted Augustine Phillips, one of the company’s principal players, and Christopher Beeston, who was Augustine’s apprentice and lodged in his house. Both were too ill to work. Fortunately, Augustine was not in the play we had just performed, and I had been able to learn Christopher’s part and so take his place. We would need to replace the two in other plays, though if the rain that still seethed outside did not end then there would be no performance at the Theatre the next day. But that problem was forgotten as the door from the hall opened and a half-dozen lords with their perfumed ladies entered. My brother bowed low. I saw the young fair-haired man with the blue-slashed yellow doublet, and was surprised that he ignored Simon Willoughby. He walked right past him, and Simon, plainly forewarned, did nothing except offer a bow.

I turned my back on the visitors as I stepped out of my skirts, shrugged off the bodice, and pulled on my grubby shirt. I used a damp cloth to wipe off the ceruse that had whitened my skin and bosom, ceruse that had been mixed with crushed pearls to make the skin glow in the candlelight. I had retreated to the darkest corner of the room, praying no one would notice me, nor did they. I was also praying that we would be offered somewhere to sleep in the palace, perhaps a stable, but no such offer came except to those who, like my brother, lived inside the city walls and so could not get home before the gates opened at dawn. The rest of us were expected to leave, rain or no rain. It was near midnight by the time we left, and the walk home around the city’s northern edge took me at least an hour. It still rained, the road was night-black dark, but I walked with three of the hired men, which was company enough to deter any footpad crazy enough to be abroad in the foul weather. I had to wake Agnes, the maid who slept in the kitchen of the house where I rented the attic room, but Agnes was in love with me, poor girl, and did not mind. ‘You should stay here in the kitchen,’ she suggested coyly, ‘it’s warm!’

Instead I crept upstairs, careful not to wake the Widow Morrison, my landlady, to whom I owed too much rent, and, having stripped off my soaking wet clothes, I shivered under the thin blanket until I finally slept.

I woke next morning tired, cold, and damp. I pulled on a doublet and hose, crammed my hair into its cap, wiped my face with a half-frozen cloth, used the jakes in the backyard, swallowed a mug of weak ale, snatched a hard crust from the kitchen, promised to pay the Widow Morrison the rent I owed, and then went out into a chill morning. At least it was not raining.

I had two ways to reach the playhouse from the widow’s house. I could either turn left in the alley and then walk north up Bishopsgate Street, but most mornings that street was crowded with sheep or cows being herded towards the city’s slaughterhouses, and, besides, after the rain, it would be ankle deep in mud, shit, and muck, and so I turned right and leaped the open sewer that edged Finsbury Fields. I slipped as I landed, and my right foot shot back into the green-scummed water.

‘You appear with your customary grace,’ a sarcastic voice said. I looked up and saw my brother had chosen to walk north through the Fields rather than edge past frightened cattle in the street. John Heminges, another player in the company, was with him.

‘Good morrow, brother,’ I said, picking myself up.

He ignored that greeting and offered me no help as I scrambled up the slippery bank. Nettles stung my right hand, and I cursed, making him smile. It was John Heminges who stepped forward and held out a helping hand. I thanked him and looked resentfully at my brother. ‘You might have helped me,’ I said.

‘I might indeed,’ he agreed coldly. He wore a thick woollen cloak and a dark hat with an extravagant brim that shadowed his face. I look nothing like him. I am tall, thin-faced, and clean shaven, while he has a round, blunt face with a weak beard, full lips, and very dark eyes. My eyes are blue, his are secretive, shadowed, and always watching cautiously. I knew he would have preferred to walk on, ignoring me, but my sudden arrival in the ditch had forced him to acknowledge me and even talk to me. ‘Young Simon was excellent last night,’ he said, with false enthusiasm.

‘So he told me,’ I said, ‘often.’

He could not resist the smallest smile, a twitch that betrayed amusement and was immediately banished. ‘Dancing with the candle-stand?’ he went on, pretending not to have noticed my reply. ‘That was good.’ I knew he praised Simon Willoughby to annoy me.

‘Where is Simon?’ I asked. I would have expected Simon Willoughby to be with his apprentice master, John Heminges.

‘I …’ Heminges began, then just looked sheepish.

‘He’s smearing the sheets of some lordly bed,’ my brother said, as if the answer were obvious, ‘of course.’

‘He has friends in Westminster,’ John Heminges said, sounding embarrassed. He is a little younger than my brother, perhaps twenty-nine or thirty, but usually played older parts. He is a kind man who knows of the antagonism between my brother and I, and does his ineffectual best to relieve it.

My brother glanced at the sky. ‘I do believe it’s clearing. Not before time. But we can’t perform anything this afternoon, and that’s a pity.’ He gave me a sour smile. ‘It means no money for you today.’

‘We’re rehearsing, aren’t we?’ I asked.

‘You’re not paid for rehearsing,’ he said, ‘just for performing.’

‘We could stage The Dead Man’s Fortune?’ John Heminges put in, eager to stop our bickering.

‘Not without Augustine and Christopher,’ my brother said.

‘I suppose not, no, of course not. A pity! I like it.’

‘It’s a strange piece,’ my brother said, ‘but not without virtues. Two couples, and both the women enamoured of other men! Space there for some dance steps!’

‘We’re putting dances into it?’ Heminges asked, puzzled.

‘No, no, no, I mean scope for complications. Two women and four men. Too many men! Too many men!’ My brother had paused to gaze at the windmills across the Fields as he spoke. ‘Then there’s the love potion! An idea with possibilities, but all wrong, all wrong!’

‘Why wrong?’

‘Because the girls’ fathers concoct the potion. It should be the sorceress! What is the value of a sorceress if she doesn’t perform sorcery?’

‘She has a magic mirror,’ I pointed out. I knew because I played the sorceress.

‘Magic mirror!’ he said scornfully. He was striding on again, perhaps attempting to leave me behind. ‘Magic mirror!’ he said again. ‘That’s a mountebank’s trick. Magic lies in the …’ he paused, then decided that whatever he had been about to say would be wasted on me. ‘Not that it signifies! We can’t perform the play without Augustine and Christopher.’

‘How’s the Verona play?’ Heminges asked.

If I had dared ask that same question I would have been ignored, but my brother liked Heminges. Even so he was reluctant to answer in front of me. ‘Almost finished,’ he said vaguely, ‘almost.’ I knew he was writing a play set in Verona, a city in Italy, and that he had been forced to interrupt the writing to devise a wedding play for our patron, Lord Hunsdon. He had grumbled about the interruption.

‘You still like it?’ Heminges asked, oblivious to my brother’s irritation.