Sadece Litres'te okuyun

Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

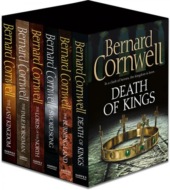

Kitabı oku: «The Last Kingdom Series Books 1-6», sayfa 18

Bir şeyler ters gitti, lütfen daha sonra tekrar deneyin

₺382,65

Türler ve etiketler

Seriye dahil "The Last Kingdom Series"