Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

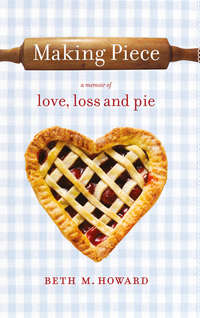

Kitabı oku: «Making Piece», sayfa 2

“And you have a safe flight to Germany,” I replied. “Let’s Skype later.” We parted with a tender kiss, our mouths touching lightly in a sort of half French kiss, until I felt self-conscious about people in the cars behind us watching and pulled away. He stayed by the car and waved until I disappeared through the revolving door. I looked back through the glass window and watched him get into his rented Subaru.

And that’s the last time I ever saw him alive.

CHAPTER 2

Three and a half months later on August 19, 2009, in Terlingua, Texas, I thought I was dying of a heart attack. I didn’t answer my phone because I didn’t have the energy to lift my head off the pillow. At 11:05 a.m., I finally checked my voice mail.

The message was from a man named Tom Chapelle, who apologized for having to call, but he didn’t have my address. Why would he need my address? Why would he need to come to my house? Hell, he would have a hard time getting to my house, seeing as I was a five-hour drive from the nearest airport in El Paso, a 90-minute drive from the nearest grocery store and I lived on a dirt road with a name not recognized by the post office.

In his message, Mr. Chapelle said he was a medical examiner and he was calling because I was listed as the emergency contact for a Marcus Iken. He used the article “a” as if my husband were an object. A car. A watch. A book. A husband. I clearly don’t watch enough television as I didn’t have the slightest clue what a medical examiner was. I scribbled down the phone number he left and my heart, which had finally slowed a little, revved right up again, double time. My hands shook as I punched the numbers into my BlackBerry.

I might not have known what a medical examiner’s job was, but instinctively I knew the call wasn’t good. Worst case, I was thinking Marcus might have been injured in a car accident. He was simply in the emergency room, waiting for a broken bone to be set. Or he had fallen off his bike and needed stitches in his head, and was unable to call me himself. During his vacation, he’d been riding his road bike a lot, going on thirty-mile outings. Surely it must have been something to do with his bike and he was going to recover from whatever injury he had suffered. He was going to be fine. I didn’t know that the job title “medical examiner” could mean only one thing.

In May, after I lost my job and Marcus flew off to Germany and I left Los Angeles for Texas, I prepared for my twenty-hour drive from L.A. to Terlingua by going to the library to check out some books on tape. Since I arrived at the Venice Beach branch five minutes before closing, I had to be quick, which meant I wasn’t able to be terribly selective. I just grabbed an armful of CDs with authors’ names I recognized. Among the titles I checked out was Joan Didion’s, The Year of Magical Thinking. I listened to it in its entirety as I drove through the tire-melting temperatures and endless shades of red-and-brown landscape, crossing Arizona and New Mexico, until I finally reached West Texas.

I couldn’t stand the reader’s voice, an affected British actress, who made poor old Ms. Didion sound like a spoiled snob instead of the devastated widow that she was. A widow. A grieving widow. The book was interesting, but it wasn’t anything I could relate to. I hadn’t lost my husband. My husband was young and fit. I hadn’t lost anyone close to me, except for my grandparents who’d lived well into their eighties when their aged bodies finally wore out. Death was not a subject on my radar. Still, I listened and the book’s opening lines stuck with me the way pie filling sticks to the bottom of an oven. “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

I stood in the living room, next to my writing desk, my hand placed on the desktop to steady myself as the medical examiner’s phone rang. He picked up after two rings and I started shaking even more. “What is your relationship to Marcus?” Mr. Chapelle asked first.

“I’m his wife,” I answered. And I was. Barely. I’d asked for a divorce and pushed Marcus into starting the proceedings. We were working through a mediator in Portland who was drawing up the papers. I didn’t want a divorce. I wanted him to fight for me, for him to say, “No! You are the love of my life and I can’t live without you. I want to stay married.”

In my perfect world, he would have also said, “I promise to work less, worship you more and, above all, be on time.” He would have said, should have said—oh, why didn’t he say it—“My love, if you say you’re going to have dinner ready at seven-thirty, by God, I’ll be home at seven-thirty. I’ll even come home at seven, so I can make love to you first.”

Had it really come down to his long work hours and lack of punctuality? We had been married a few days shy of six years. That’s six years of cold dinners and hurt feelings. Six years of moving from country to country, continent to continent. Setting up a new house with each move; taking German lessons and then Spanish lessons; making new friends; saying goodbye to those friends and then making new ones again. Six years of trying to get Marcus to acknowledge me, what I needed, how much I wanted our marriage to come first and how his work, his schedule, his priorities were wearing me down.

Before we got married, during our year-and-a-half-long courtship, the majority of time I spent with Marcus was when he was on vacation. Europeans get six weeks of holidays, which meant six weeks with Marcus in laid-back mode, Marcus wearing jeans and reading books, not donning a suit, not checking his email, not coming home late. He cooked for me. He grilled steaks and shucked oysters. He did my laundry. He washed the dishes. And he made love to me for hours. It’s no wonder I wanted to marry him!

But that was on my home turf. When I moved to Germany, everything changed—Marcus changed. When he put on his suit and tie, he became a different person.

“What about me?” I pleaded time and again. “Our marriage centers only on you and your job, your promotion, your schedule. What about my career and my happiness? What about where I want to live? Why can’t we pick a place we both want to live, a place where I can speak the language and not feel so lonely, and just move there and we can both get jobs?”

We eventually moved to Portland and that helped for the year and a half we lived there. But then Marcus, thanks to his steady corporate executive career climb, got transferred to Mexico and we were right back where we started. My unanswered questions inevitably escalated into louder cries, harsher words. “I want to be in an equal partnership. Instead I feel like you just expect me to serve you!” I shouted. “I have a life, too!”

I had a life, all right. And now he didn’t.

Joan Didion’s suggestion that “life changes in the instant” might have been true for her. She was physically there in the room when her husband’s heart stopped and caused him to fall out of the chair and hit his head on the corner of the table on the way down. She saw him lying on the floor, unresponsive, his head bleeding. She had proof, evidence, visual aids. She could put her fingers on his pulse and feel he didn’t have one. She could blow air into his lungs and watch his chest rise. She could call 911 and watch the paramedics as they stormed into her apartment and hooked up their electrodes and squeezed their syringes. Being there, in person, absorbing the immediacy of the action, then yes, time must have felt compressed into an instant.

News—specifically bad news—when delivered over the phone causes time to take on a different dimension. With no visual cues, there is nothing for the mind to grasp but whatever is imagined—drama, gore, violence, struggle, pain—combined with fleeting, movie-clip-like flashes of memory. There is no proof. There is only the voice of a stranger on the other end of the line. Someone you don’t know, don’t want to know, don’t want to believe. Someone in a government building 2,000 miles away. Someone who has never met your husband, who sees the man you loved only as a corpse lying on the examination table, waiting for an autopsy.

With this one phone call, life as I knew it ended.

“Your husband is deceased,” he said, his voice deep and gravelly. He had the air of a military officer, serious, official, no emotion, detached. I could just picture the man sporting a crew cut, fleshy jowl, perfectly starched shirt, maybe even khaki in color, with the buttons pulling tightly across his ample belly. Deceased. The word didn’t register at first. Deceased? No, that can’t be. Injured is what I had expected him to say. Hurt in a car accident or from a fall off his bike, just out of surgery but recovering nicely. Not deceased. Not Marcus. Not healthy, robust, sexy, stubborn Marcus.

I would sell my soul to turn back the clock, to never get a call from a medical examiner and continue living in my happy oblivion to never even know what one was. I wish with every cell in my body to go back three and a half months earlier to May 5, the day Marcus dropped me off at the Portland airport. I wouldn’t get on the plane to L.A. I would fly to Germany with him instead, and worry about getting my belongings there later. Or I would turn the clock back even earlier. Five years, five months, it doesn’t matter. I’d settle for turning the clock back five hours. Maybe that way I could have saved him. I still want to save him. I still want him to be alive. Seven hours before Marcus was supposed to sign his half of the divorce papers, I killed him. I asked him for a divorce neither of us wanted and I killed him. To verify this, I asked Mr. Chapelle in a meek tone that didn’t sound anything like me, “Was it suicide?” The words snuck past my vocal cords and tiptoed out of my throat, which tightened with each passing second. It was the worst thing I could have asked; I was ashamed for asking it, but I had to know.

“No,” he answered quickly. “It was something with his heart.”

Of course, it was his heart. I broke it. He wanted to stay married and this was his way of making that happen. This was the second time we tried to divorce, and the second time we didn’t sign the papers. We were still married. And now we would be married forever. That’s a hell of a way to avoid divorce.

“The divorce almost killed both of you,” my sister said later. It hadn’t occurred to me, but she was right. During the hour he was struggling to stay alive after collapsing from a ruptured aorta, I felt my heart about to give out, thinking I would collapse in the middle of the Chihuahua Desert. I turned to go back home at 8:36 a.m.—that was 6:36 a.m. in Portland, the exact time Marcus was pronounced dead. Is it possible we were that connected? Were our bodies functioning in unison, joined by some inexplicable force? Was I feeling what he was feeling, the struggle of his heart to keep beating? While he was hit with defibrillator paddles and receiving epinephrine injections, I was enduring my own struggle, staggering with weakness back to my miner’s cabin with my dogs—our dogs.

I had a few hours to contemplate my death, but did he know he was dying? The details that were parceled out over the next few days concluded no, he could not have known. It was instant. He felt a cramp in his neck, got out of bed, took a few steps and collapsed on the hardwood floor of a friend’s house.

I imagined him having one of those out-of-body experiences, floating above his body, looking down and seeing himself lying unconscious on the floor, and saying, “What the fuck just happened?” This is a man who wanted to live. He had just invested in a new MacBook Pro and an iPhone. He had a pile of new books including The Passion Test, What Color is Your Parachute and What Should I Do With My Life? And he had bookmarked his favorite new website, “Zen Habits,” which was all about doing less to accomplish more. After years of my incessant nagging, he was actually exploring ways to trade in his corporate life for something more balanced. Back in Germany, he had also just bought a new road bike, a sleek and fast-looking LaPierre, which he had shown me via Skype. He sent me emails from his weekend bike rides in France, Italy and even Slovenia. This was a man with a lot of life left to live and big plans for the future. He was only getting started.

The autopsy determined he died from a hemopericardium (blood flooding the heart sack until the heart cannot pump any longer) due to a ruptured aorta. Marcus had a heart condition from birth, a bicuspid aortic valve, which means he had only two flaps to allow oxygenated blood to flow out from the aorta instead of the normal three. Blood pumping through the aorta is under high pressure. Having only two flaps creates a bottleneck and puts added pressure on the aortic wall. The wall had a weakening that eventually tore. Unless it happens when you are already in a hospital, a ruptured aorta is always deadly. There is no grace period. The blood moves too fast. The heart suffocates. And bam! Just like that. The man you love is gone.

His German doctors had always maintained his heart condition would never be a problem. Had Marcus known how endangered his life was, he would have taken precautions. He was that kind of guy: disciplined in everything he did, especially when it came to his diet (only the highest quality, organic, wild-caught everything for him). He didn’t smoke, he exercised regularly, doing yoga, biking and running, and he loved being outside in the sun breathing fresh air. This was a guy who was so health-conscious, he flossed his teeth three times a day. Who does that? No, he was not supposed to die. Not like this. Not at forty-three. Not ever.

My brain spun with centrifugal force after hanging up with Mr. Chapelle. I looked around the living room of my miner’s cabin in a wild panic. My body shook with convulsions. My eyes widened with disbelief. My breathing turned to hyperventilating. I paced back and forth between the desk and the daybed. I had no idea what to do. Did I really just get a phone call telling me that Marcus was deceased? Deceased. I hate that word. What a miserable word. If only I could have taken that word and shoved it through the phone line, stuffed it back into the mouth of the man who uttered it, crammed it all the way down his throat to extinguish it so he could never say it. If he couldn’t say it, then it couldn’t be true.

My first call was to our divorce mediator in Portland. “He’s in a meeting,” his secretary said.

“It’s urgent,” I told her. She must have heard the panic in my voice—high-pitched, sharp and forceful. She put me through.

“Marcus won’t be coming in for his one-o’clock appointment. He died,” I blurted out. “He’s dead. He had a ruptured aorta.” And then my composure crumbled. “I don’t know what to do! I don’t know what to do! I don’t know what to do! I don’t know what to do!” I kept repeating myself, practically screaming in hysterics, as I entered into full-blown panic. To say it out loud to someone else, to acknowledge that which I desperately did not want to be true, made it just a little more real. Was it really true?

I could detect Michael’s shock in spite of his attempt to calm me. He was a Catholic-turned-Zen Buddhist, which he had told us when we interviewed and subsequently hired him to help negotiate our separation. Marcus was in Portland and thus met with him in person several times. I was only connected by conference calls and had never seen him, but based on his gentle voice, relaxed manner of speech and his respect for Marcus’s and my determination to remain amicable, he seemed nice—for a former litigation lawyer. He had changed his career to mediation because it seemed, well, less litigious. “Take a breath,” he said. “Settle down. You’re going to be okay. Here’s what you do.”

He outlined the next steps for me. Someone had to instruct me, because I couldn’t think straight. I couldn’t think past the image of Marcus and his lifeless body lying in a morgue thousands of miles away. No! I could not, would not, picture that. My mind was still insisting he was alive. He had to be alive. This was all a mistake. This wasn’t really happening.

“Book your flight to Portland,” Michael said, snapping me back to the present. “Call his parents in Germany. And above all, take care of yourself. You need to make sure you are okay. Do you have someone there who can be with you?” I didn’t. Betty, my landlord, was in El Paso for a few days. I had only my dogs and I was already scaring them. Daisy was hiding under the bed and Jack kept trying to lick my face, something he was prone to do when he was insecure.

I wanted to fly to Portland that evening. There was a flight available, and even with the five-hour drive to the El Paso airport, I could have made it. But when I discussed it with Mr. Chapelle, he said there was no reason to rush. It wasn’t like I needed to get there in case Marcus might take his final breath. He was already gone.

I spent the entire night awake; first tossing and turning in my bed until finally, so disturbed, so much wanting to crawl out of my skin to escape the searing pain, I moved into the living room and lay on the concrete floor in front of the fan. My forehead, pressed into the painted cement, rolled back and forth, practically wearing a groove into the hard floor as I wailed and wailed and wailed. I never heard such loud, guttural cries emitted from so deep within my core, never knew noises such as these were possible. I sounded like a dying animal, moaning like a cow hit by a car and left for dead on the road, wishing for someone to shoot it and put it out of its misery.

And I did feel like I was dying. I wanted to die. My moaning, my wailing, my cries could have been heard as far away as El Paso. But no matter how much, how long and how hard I cried, I couldn’t get the pain out. This new form of agony—sizzling, burning, tearing at my heart with razor blades—was an alien being that took over my body, infiltrating every cell. I couldn’t hold still. I couldn’t cry hard enough. I couldn’t scream loud enough. I couldn’t get the emotional torture to stop.

Psychologists call it complicated grief. It was almost a relief, as much as I could fathom any inkling of relief, to learn a few months later that what I was experiencing had a name, a clinical term. I had a condition. I could be placed in a category, given a label. I could wear a sign around my neck that read “Caution: This woman is suffering from complicated grief.”

Complicated grief is when someone you are close to dies and leaves you with unresolved issues, unanswered questions, unfinished business. And guilt. Lots and lots of guilt. And pain. Bottomless depths of searing pain. Complicated grief is when you ask your husband for a divorce you don’t really want, and he dies seven hours before signing the papers.

I killed my husband. I was sure of it. It was my fault. I’m the one who pushed for a divorce. He didn’t want it, must not have wanted it, otherwise he wouldn’t have died. He was dead, we were still married, and that told me everything. Before leaving my miner’s cabin for Portland, where my husband was reportedly dead, before putting my dogs in the care of my British neighbor, Ralph, I rummaged through my toiletry bag and found my wedding ring. The ring, an exact match to Marcus’s, was a band of fine gold on the outside, with an inner ring of steel on the inside. The bands were connected, yet separate, and made a jingling sound when they moved against each other. We had our rings designed by a goldsmith friend of Marcus’s in Germany to represent us—our strong bond balanced by our independence—and our lifestyle, the contrast of our love for both backpacking and five-star hotels.

I slid the ring back onto my finger where my white tan line had turned brown in the Texas sun, and shook my hand until I heard the familiar jingling. The gentle rattle had become a nonverbal communication between Marcus and me. We would shake our rings in each other’s ears as a way to say, “I’m sorry, I still love you” after an argument, when it was too difficult or too soon to utter the words out loud. I had taken the ring off even before I asked Marcus for the divorce. I took it off because I was mad at him. Mad that I couldn’t fly to Germany for my birthday in June to spend it with him. Because the auto industry was forced to make job cuts, Marcus was working two jobs and therefore he was too busy for me to visit. He started his days at 6:30 a.m. and returned home—home, which translated as a guest apartment attached to his parents’ house—no earlier than 9:30 at night, night after night. He was exhausted. I could hear it in the irritable tone of his voice. I could see his fatigue when we talked via Skype. I felt bad for him, but I was also hurt.

“What about me? I’m your wife. Am I not a priority?” I continued to plead. I hadn’t seen him since May. June came and went. And then there was July, a month during which he developed a chronic cough. “Don’t be like Jim Henson,” I chided. “You know, the guy who created The Muppets. He was sick but refused to take any time off work. It turned into pneumonia, and look what happened to him.”

Marcus insisted he was fine. His doctor told him his lungs were clear, it wasn’t bronchitis, gave him an asthma inhaler and sent him home. If only the doctor had checked his heart, had used ultrasound equipment to inspect his aorta, checked the thickness of its wall, had seen that there was a weakening and performed emergency surgery to put in a stent. If only.

Marcus spent his 43rd birthday on July 2—having no clue it would be his last—buying his new road bike. He still had no time for me to visit. His August vacation was coming up, so we assumed we would just wait and see each other then. I was looking forward to seeing him. I missed him. I missed his body, his shapely soccer-player thighs, his perfect, round ass. I missed his scent, or lack of scent, maybe it was just his presence I longed for. I missed spooning against his smooth skin, his chest hair tickling my back. This was the longest stretch of time we’d spent apart since we met—and, no, Skype sex doesn’t count.

“Let’s make a plan,” I suggested.

“No,” he said. “Every minute of my life is planned out for work. I don’t want to make any plans right now. I’m too tired.” And that was it. That was my breaking point. He didn’t want to make plans for his August vacation—our vacation. I felt cast aside, not important enough for him to pencil me into his calendar. Work always came first. So I asked for a divorce. “You don’t want to make plans? I’ll make them for you. Instead of coming to Texas, you can spend the three weeks in Portland filing the papers.”

He still wanted to come to Texas. He said, “I’ll come there and we’ll talk through our issues.”

“If you come here,” I replied, “we’ll have a good time like we always do. We’ll drink lattes and wine, we’ll go hiking with Team Terrier, we’ll make love and then we’ll be right back to where we were.”

“Yes,” he said. “You’re right.”

Why, oh, why, OH, WHY didn’t I let him come? Why did I have to be such a hard-nosed bitch? “But what if he would have died in Texas?” friends argued. “It’s so remote, you couldn’t have even called an ambulance. You would have never forgiven yourself.” Forgiveness? I couldn’t forgive myself for any of this. I killed my husband. It was my fault. If only I had let him come to Texas, he would still be alive.

I don’t know what normal grief is like, but complicated grief? Complicated grief must be grief on steroids.

The physician’s assistant of Terlingua didn’t give me an appointment to check my racing heart—my heart which was also now broken, shattered beyond repair. Instead, he gave me a ride to the El Paso airport. We didn’t speak for the duration of the five-hour pre-dawn drive. He left me to my silence as I stared numbly out the open window, feeling the hot Texas wind in my face. I flew from Texas to Portland into the arms of my best friend from childhood. Everyone needs a friend like Nan. Nan is the friend who, when you tell her the news—the Very Bad News that you’re still having a hard time believing is true, but since Marcus didn’t call the entire day after Mr. Chapelle’s call, and he never went a day without at least sending an email, I was beginning to believe could be true—well, Nan takes charge.

“You don’t have to come to Portland,” I told Nan. She didn’t listen. Not only did she book a flight from New York, a rental car and a Portland hotel, she made sure her flight arrived before mine, so she could scrape me off the airport floor and carry me to the car.

Marcus and I had three weddings, so it seemed fitting that we had three funerals. We first got married at a German civil service in the picturesque village of Tiefenbronn, where we signed our international marriage certificate with Marcus’s parents as our witnesses. Next, we got married on a farm outside Seattle, Washington, not only to accommodate my friends and family, but also because I had been freelancing for the past year at Microsoft and therefore Seattle was my most recent U.S. base.

We saved the best for last and returned to Germany, where we took over the tiny Black Forest hamlet of Alpirsbach, booking rooms for our guests in all the charming inns, hosting dinners at cozy Bierstubes and walking down the aisle in a thousand-year-old cathedral, a towering beauty built of pink stone. Three weddings, three different styles, from basic to rustic to elegant. His funerals mirrored our weddings, albeit with a lot more tears—and definitely no champagne.

I didn’t see his body until I had been in Portland for five days. I was still going on trust to accept that he was actually dead and hadn’t instead plotted his disappearance to some tax haven where he was now living on a yacht with a supermodel. It wasn’t until the day of the Portland funeral that I laid eyes on him. I had already picked out clothes for him to wear—a black linen shirt, his favorite wool bicycle jersey tied around his shoulders, Diesel jeans and his clogs. He had to wear his clogs.

And then, there on Broadway and 20th, in the understated pink-and-beige-toned parlor of the Zeller Chapel of the Roses, two hours before the Portland service was to begin, I saw him. It was him, strikingly handsome and healthy looking, even when filled with embalming fluid. It was the man I had fallen in love with, was still in love with, the man I had married, was still married to. I saw him. I talked to him, begged him to wake up. I held his hands, bluish and hard. I ran my fingers along his forehead, bruised from his collapse. I leaned down into his casket and kissed his cold lips that didn’t kiss me back. Now I knew it was true. He was dead.

My tears cascaded down like Multnomah Falls and they didn’t stop for ten months. They ran and ran, creating permanent puffy eyes and altering my face with so much stress old friends no longer recognized me. The tears ran the entire flight to Germany, while I sat in business class and Marcus flew in a metal box in cargo. The tears flowed all through the week I spent in Germany, from the moment his grief-stricken, ashen-faced parents picked me up at the Stuttgart airport, to when they took me to the guest apartment where Marcus’s suits were hanging in the closet.

My tears kept on flowing through the German funeral, a formal and elegant church service, packed with Marcus’s coworkers, accompanied by a quartet of French horns playing Dvorak’s “From the New World” and presided over by the same pastor who’d married us. The tears gushed through the informal and quiet burial of Marcus’s ashes, and through the final meeting at the Tiefenbronn Rathaus, the place where we had signed our marriage certificate, and where I was required to sign his death certificate.

The tears came in endless waves. They came by day, by night. My tears did not discriminate in their time or place. From Germany, my tears followed me back to Portland, and then back to Texas, where I collected my dogs, packed up my MINI Cooper, said goodbye to Betty, goodbye to my miner’s cabin, goodbye to the desert that had nurtured my creativity all summer, goodbye to life as I had known it. The tears were ever-present, ever-flowing. It was a wonder I wasn’t completely dehydrated. There was only one thing that defined me now: grief. Complicated grief. Grief on steroids. It was something I was going to have to get used to.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.