Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Like Bees to Honey»

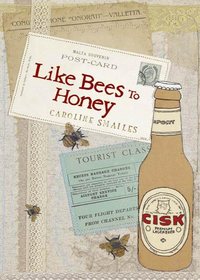

Like Bees to Honey

~b an-na

an-na al lejn l-g

al lejn l-g asel

asel

Caroline Smailes

Remembering, always, my grandparents George Dixon and Helen Dixon (née Cauchi).

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Excerpt

Xejn

Wie ed

ed

Tnejn

Tlieta

Erbg a

a

êamsa

Sitta

Sebg a

a

Tmienja

Disg a

a

G axra

axra

dax

dax

Tnax

Elena

Tlettax

Erbatax

mistax

mistax

Sittax

Sbatax

Tmintax

Tilly

Dsatax

Tilly

G oxrin

oxrin

Wie ed u g

ed u g oxrin

oxrin

Flavia

Tnejn u g oxrin

oxrin

Tlieta u g oxrin

oxrin

Tilly

Erba’ u g oxrin

oxrin

amsa u g

amsa u g oxrin

oxrin

Sitta u g oxrin

oxrin

Seba’ u g oxrin

oxrin

Tmienja u g oxrin

oxrin

Disa’ u g oxrin

oxrin

Tletin

Wie ed

ed

Nixtieq nirringrazzja

Preview

About the Author

Also by Caroline Smailes

Copyright

About the Publisher

Excerpt

‘You sent for me sir?’

‘Yes Clarence. A man down on Earth needs our help.’

‘Splendid! Is he sick?’

‘No. Worse. He’s discouraged. At exactly 10.45 p.m., Earth-time, that man will be thinking seriously of throwing away God’s greatest gift.’

~It’s a Wonderful Life, 7 January 1947 (USA)

Xejn

~zero

Christopher Robinson, born 20 December 1991.

I remember the exact moment when Christopher first realised.

We were standing together, in my mother’s kitchen, in Malta. He had been unusually quiet.

I asked him, ‘What’s wrong Cic io?’

io?’

He looked up to me and whispered, ‘Can you see the mejtin too, Mama?’

~dead people.

I looked at my five-year-old son, shocked, confused, thrilled.

‘Dead people,’ he translated. ‘Can you see the dead people too, Mama?’

Wie ed

ed

~one

Checking In:

Please allow ample time to check in. Check-in times can be found on your ticket, by contacting your local tour operator or your chosen airline. Our broad guidelines state:

Please ensure that you check in three hours before departure for long-haul flights.

Please ensure that you check in two hours before departure for European flights.

Please ensure that you check in one hour before departure for UK and Ireland flights.

I am focusing on the woman, the one in front of me, her, with the black high high heels. She is wearing tight white jeans. I think they call them skinny jeans. She is wearing white socks and black heels, her. My son, Christopher, is standing next to me. He will not speak. I am focusing on her. I am focusing on her calves and on her black shoes. The heels are caked in mud, dry mud, around the tip of the cone. The mud is speckled up the back of her, of her calves, over her white skinny jeans.

I wonder if she realises.

We are standing in the queue. We move forward slowly. I have wrapped my large shawl around my shoulders, I roll the tassels with the fingers of my right hand. In my left hand I am clutching a small clear plastic bag containing a lipstick that does not suit and mascara that is almost empty, beginning to cause flakes on my lashes.

As we reach the security arch, Christopher walks through, no sound, no signal, no attention is given to him. I shout for him to wait. People turn and look from me and then towards where I am shouting, screaming.

Nobody asks.

Christopher carries on walking, ignoring me, he is angry. I know that I have upset him. I am anxious to reach him, uneasy when he moves from my sight. I wonder if it will be the last time that I see him, I wonder if he will finally have had enough of me, of the way that I have become.

I am stopped.

I am forced to remove my boots, empty the pockets of my jeans, be frisked with a detector that beeps. I take off my belt, I take off my boots. I look to my feet. I notice that my socks do not match.

Airport security is tight, these days. I smile. I smile as they appear to have let through my son, unnoticed. I am still smiling as I slip back into my knee-length boots. I am still smiling as I move over to the conveyor belt, searching for my handbag. I do not think that the officer likes my smile; he holds my handbag into the air, accusingly.

‘Is this your bag?’ the officer asks.

‘Yes,’ I say.

I look to the officer in his black uniform, with his shiny shoes and his shaven head. I wonder if he is proud, I wonder if he holds his head up high as he fights to save Manchester airport from terror. I like him, I decide.

‘Are you travelling alone?’ he says.

‘No my son’s with me, he’s…’ I point after Christopher. The officer flicks his eyes to there and then to me.

‘Work or pleasure?’

‘Pleasure,’ I answer. I stop.

And then, I remember.

Christopher is waiting for me when I walk around the corner, out from security. He is leaning on his shoulder, against the white wall. He still refuses to speak. I scold him; I shout and scream that he is not to leave my sight, ever, again. He remains silent. He stares down to his canvas shoes, his favourite shoes. He will not look at me. I wish that he would. I wish that he would speak. Tourists, passengers, they all stand and stare.

Christopher waits for me to finish shouting. His cheeks look blushed. I am wagging my finger, my eyes are wide, my voice is shrill. I am embarrassing him; of course I am, he is sixteen.

Two security guards turn the corner. They stand still. Their legs are apart, their arms cross their chests. A third security guard appears, he is mumbling into a radio. I finish shouting; it has been one maybe two minutes. I do not like being watched.

I tell Christopher that I need a coffee. He walks off, still looking down at his canvas shoes, still silent. I follow. He is guiding my way.

The airport is busy. I do not know why I expected stillness, a silence. It is 4 a.m., a Thursday, flights come and go all through the night. I know that. I do not know why I needed a silence.

or why I expected a hush, a hush hush.

~hu – sshhhhh.

~hu – sshhhhh.

Christopher is sulking, not talking to me and I do not have the energy to pander to him. I am trying not to focus on him, not to give him negative attention. Instead, I am listening.

to the grrrr.

~grrrr.

~grrrr.

of the milk steamer.

~grrrr.

~grrrrrrrrr.

~grr.

~grrrrrr.

The noises lack symmetry.

The coffee shop is crowded. There is not much else to do, but to drink, to eat, to wait to be called for boarding. It is 4:20 a.m. I have purchased a coffee, nothing to eat, no thick slice of cake, no huge muffin, just a tall café latte, no sugar and a child’s milk for Christopher. He hates to be called a child. There is music, unrecognisable. Looping notes with a tinny edge, what the Americans would call elevator music, I think. I wonder if I am right.

I used to dream of going to America, one day.

there is the whir.

~wh – irrr.

~wh – wh – irrr.

~wh – wh – irrr.

of the coffee machine.

then the grrr, again.

~grrrr.

~grrr.

~grrrrrrrrr.

of the milk steamer. There is the dragging scrape of the till drawer.

and the clink.

~cl – ink.

~cl – ink.

of the coins.

And then I realise that Christopher has gone. He has wandered off, again. He does that a lot, these days. I will not look for him. He will find his way, I reason. He will come back, he has come this far. He knows that he must take this journey with me, for me. He has been told that he has to escort me back to the island.

I need to telephone Matt.

I have left my mobile phone at home, in the kitchen, close to the kettle. Matt will have found it, by now. It is 4:30 a.m. and I know that I should not be calling my husband. He will be in bed, perhaps sleeping, but we have that telephone in our bedroom.

I find a payphone. I fumble in my bag, in my purse, for loose change. I lift the receiver, insert a 20p, press the number pads, wait.

It is ringing.

With the ring, I can see him stretching over the bed, I can see him in his sleepy haze, a panic, reaching his naked arm out, to answer, to grab.

‘Nina?’

‘Yes,’ I say.

I can hear crying, sobbing in the background.

‘She needs to speak to you. Will you speak to her?’ asks Matt.

I do not have time to answer.

‘Mama?’ She is sobbing, making the word high pitched.

‘Molly, Molly pupa. Stop crying,’ I say.

~my doll.

I am trying not to shout. People are listening.

I am sure that, I think that, the grr.

~grrrr.

~grrrrrrr.

has stopped and the whir.

~wh – wh – irrr.

~wh – wh – irrr.

has stopped too.

People can hear me.

‘Mama, you didn’t kiss me bye bye.’ Molly tries to stifle her heart, but I know that it is broken.

And then, suddenly, I am missing her too much.

And then, suddenly, my throat is aching and I need to cry and I need to scream and I need Christopher. I need for him to remind me why I have left my little girl, my four-year-old daughter, my pupa.

~my doll.

It is late, it is early, she will be tired and emotional, more emotional than usual. I am reasoning with myself, but I know, I know really. I know within that I have hurt my innocent.

I hang up.

I hang up on her sobs, leaving her to Matt. Her daddy.

I need to see Christopher.

I am walking around the departure lounge, searching, sobbing, snot dripping from my nose, tears cascading down my cheeks.

I find him.

He is squashed in between a couple, tourists, I presume. The woman tourist’s hair is bleached white, she wears a short short skirt and I see that her thighs are fat and dimply. She wears blue mascara, it clogs on her lashes; her lips are ruby red and her skin is orange. I do not look at the man tourist. Christopher smiles, briefly. Then he squeezes out from in between and he is off, again, running.

I refuse to chase him. I turn to walk away.

‘Are you alrite, pet?’ the woman tourist asks.

‘I’m fine,’ I turn, I say. ‘Thank you,’ I say, I start to turn and walk.

‘It’s just you was crying like a bairn a bit ago. I says to me bloke, “Look at that lass crying.”’

‘I’m fine, honest, I thought I’d lost my son,’ I say.

‘Shit,’ the woman tourist says. ‘Have you found him?’

‘Yes he’s there –’ I point, I turn, I walk away.

I find Christopher, standing below the departures’ board, straining his neck to read the listed times. The details for our flight have changed; we need to make our way to gate 53. We walk together, in silence.

All of the tourists have crowded to the gate. Christopher stays close to me, intruding on my body space. We do not have a seat. I am leaning onto the white wall, Christopher is leaning onto me. I think that he is feeling anxious. I am still sobbing. I wonder if he fears that I will change my mind, that he will fail his task, again.

‘Air Malta flight KM335 is now boarding from gate number…What gate are we?’ The crowd of tourists laugh, ha ha ha.

‘Yes. From gate number 53. Would all passengers please make their way, with their boarding cards and passports open at the photograph page.’

There is the usual scurry, the fretful rush of people desperate to claim their pre-booked seat. I do not move, neither does Christopher. I am standing, leaning, waiting for a realisation. I am waiting for some bolt of enlightenment, for something to enter into my head and to stop me from boarding the plane.

The bolt never comes.

The muffled sobbing continues, but still I am boarding the plane. I am leaving my Molly, my pupa.

~my doll.

I have no plans to return.

Tnejn

~two

Air Malta is not only committed to provide you with a comfortable journey, but also to give that extra personal touch…

The doors have been closed, security measures have been explained. I did not listen or watch. Christopher is virtually on my knee, squashing in between me and the passenger next to me. He is fidgeting, wriggling, annoying.

‘Sit still,’ I tell him.

He looks at me but does not speak. We both know that the plane is ready to lift us from that ground.

the engines are whirring.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

and as my head falls back to the headrest, the engines whir some more.

~wh – hir.

~wh – hir.

then the plane darts forwards, upwards, it tickles into the back of my throat. I swallow, forced gulps.

I look out through the small oval window, the houses and cars become insignificant. I see the clouds. I am flying over the clouds. I am flying over a blanket of greying white that separates and joins. I am in the air, higher and higher.

And then I realise.

I am gone from his England.

I wrap my large shawl around my shoulders. I bring the two ends together, up to my face. The shawl has tassels, the tassels tickle me, annoy, remind me. I wore this shawl when Molly was a baby, before she began toddling. I can remember her curling into me, fiddling with the tassels, rolling them between her tiny plump fingers, pulling them up to her mouth.

I want the smooth material close to my face.

I am sobbing.

~s – ob.

~s – ob.

~s – ob – bing.

into my shawl.

I am dripping.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip – ping.

snot and tears into my shawl.

The plane continues to move higher and higher above the clouds. I continue to sob, muffled sobs.

I have become the flight maniac. I want to apologise to the passenger beside me. He is dressed in a casual suit, creased slightly; his shoes are shiny, polished and buffed. I want to tell him about my life and my loss, but I do not. Of course I do not.

I am the flight maniac.

telling him my story, loudly, over the sound of the whir.

~wh – ir.

~wh – irr.

whirling engine, would only make things worse.

And so I continue to stifle my sobs. And the passenger beside me turns away, his left shoulder protruding, twisting awkwardly.

Christopher does not speak. I think that he may be sleeping.

The seatbelt sign goes off.

the plane is filled with the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal.

And within the minute, there is a queue for the toilet, four men and one woman line from the drawn curtain and down the centre aisle. She looks pregnant, the woman. Her stomach is large, egg shaped; her palm is resting on it. I wonder if she is having a girl or a boy.

I want to talk to her. I need to talk to her. She must be able to smell food.

I really should buy her food.

I grew up on the island of Malta, in a close neighbourhood, with open window and open door. The community liked to cook and the odours of our foods were rich. They decorated, they floated in the air, breads, sweet pastries, baking potatoes, spice-filled macaronis, soups that celebrated local vegetables. This meant that a pregnant woman, whoever she might be, would smell the food and that with that smelling her baby would feel a desire, a need. And so, in Malta, without request, all from the community would know to take a dish of any food being prepared to any pregnant neighbour. It was almost a law, I think. It is said, in Malta, that the food will feed the desire of the baby. If a pregnant woman does not have, does not eat all that her baby craves, then it is said that the child will be born with a birthmark, a mark with a suitable shape.

I remember that my mother had a notebook.

She would write down the names of our pregnant neighbours and I remember that when one of our neighbours was heavy with her fourth child, my mother, she told me, ‘Nina, listen, take this to Maria.’ She told me, ‘I do not like her but her baby must have what it desires. Take her this.’

I remember looking down to see my mother holding a dish of minestra.

~a vegetable soup containing local or seasonal vegetables, potatoes, noodles.

We had many mouths to feed with our daily food, yet still we would feed a baby of a neighbour. The bowl was hot, my mother’s vegetable soup sloshed as I walked down the slope to Maria’s house. I remember that it was summer, the tall houses sheltered from the burning sun, the cobbles were cool under my naked feet, the dust swirled from recently brushed doorways. The smell of the minestra, so rich and sweet, danced and twisted up my nostrils. I remember the liquid spilling onto my fingers, burning and my longing to taste the food, but, of course, I would not, could not even. I had learned not to deprive a baby; I could not even lick my fingers. I remember walking the cobbles, slowly, slowly down the slope and I remember Maria answering the door.

She told me, ‘I will not eat the food of your mama’ and then closed her front door, with a slam. I knew better than to return home with the minestra and so I left the bowl to the left of her step, where she could not trip over it. And I shouted loudly, told Maria that her baby’s food was outside.

Three months later my mother told me, ‘Nina. Go look. Maria’s baby has the mark of a broad bean.’

I stare at the swollen stomach of the tourist on the plane. The queue is slow. She is leaning now, against an aisle seat. I look to her face. She is young, she appears tired.

I remember how tired I was when pregnant with Molly.

I push Christopher off me, slightly; he continues to sleep. I stand, place my shawl onto my seat and walk to her. I do not like walking on planes. My feet seem too light, like I have marshmallows on the tips of my heels. I squish my way to her.

I reach her.

‘Are you hungry?’ I ask.

‘Sorry?’ She looks frightened.

‘Can you smell food?’ I ask.

‘Sorry? No. Please.’ She is frightened.

‘You must eat whatever you smell,’ I say.

I turn, I walk from her, squishing my marshmallow-tipped heels, not looking back. I find my seat.

I move Christopher to one side; I sit.

I look to the pregnant woman. She is talking to the man in front of her; they are looking at me. She is full of fear. I need to reassure her. I know that she is frightened, but she must eat.

I mouth words to her.

I mouth, do not worry.

I mouth, I do not have the evil eye.

I mouth, you must eat what you smell.

I wonder what shape birthmark her child will have.

and then I realise that I have started.

~s – ob

~s – ob

sobbing, again.

I really am the flight maniac.

I have woken Christopher with my moving about, with my sobbing.

‘Iwaqqali wi

i l-art.’

i l-art.’

~you embarrass me/you make my face fall.

I stare at him, stopping my sobbing, allowing tears to trickle and snot to drip, but no sound.

‘Iwaqqali wi

i l-art.’

i l-art.’

~you embarrass me/you make my face fall.

‘Who taught you that? Who taught you that?’ I demand.

‘It’s ilsien pajji i.’

i.’

~mother tongue.

‘How? Tell me how,’ I demand, again.

Christopher does not answer.

The small television screens come down, a graphic of a toy plane is edging slowly over the UK, heading South. The air steward tells us that headsets can be bought, the film starts. Live Free or Die Hard, I am glad that I cannot hear the words. Christopher is watching the screen.

A child, across the aisle, says, ‘For fuck’s sake.’

I turn. He is twelve, maybe younger. His mother smiles at me, briefly.

And I think of Molly, again.

tears drip.

~dr – ip.

~dr – ip.

again.

It is nearly 6 a.m. I think of her getting dressed. I wonder if Matt will send her to school. I think of her hair and of how Matt cannot manipulate bobbles, cannot bunch or plait. He may use the wrong brush, tug at her tats, not hold the hair at the root. I think of her crying out with pain.

I think of the mums in the school playground, of how the news will spread in hushed tones. I think of how they will fuss around Matt, eyes full of pity, of how they will never understand what I have done. I think of how he will have to excuse me, talk of grief, and how they will say that six years of grief is excessive.

And I know that they are right.

I think of Molly’s pink sandwich box, of routine, of her tastes, her quirks. I think of Matt struggling to find clean uniform, to dress, to juggle his work and his Molly. I know that he will be late for work if he waits for her to be clapped into school from the playground.

My thoughts are confused, jumbled, whirling.

I can still hear her sobbing.

I hope that Matt keeps her from school today, just today. He will need to go in to see the Headmistress, or telephone her, or both. The teachers will have to be told what an evil mother I am, of how I have abandoned my daughter and run away to a foreign country with my only son. But I know that any words exchanged will be missing the purpose, the point, that they will never fully understand why. I know, I appreciate, that people will be quick to judge me. I would hate me too. But, still, leaving my Molly, leaving my beautiful girl is dissolving any remnants of my remaining heart.

I think of her.

And then, suddenly, I am missing her, too much.

My sobbing vibrates through my body; it causes me to snort snot from my nose. My sobbing causes tears to stream.

and my shoulders shudder.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

~shud – der.

beyond control.

I am out of control.

I pull my large shawl tighter around my shoulders. I bring the two ends together, up to my face, again. I bring the smooth material onto my face, until it covers my eyes, my nose, my being.

I breathe into my shawl.

I wonder if my Lord is laughing at me.

She wakes me.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’

I forget; for a moment, I am unsure where I am.

‘Would you like any food or drink?’ she repeats.

I look at her trolley. I see tiny bottles in a drawer.

‘Two whiskies, please,’ I say.

‘Ice?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘A mixer?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Anything else?’

I look to Christopher, he is absorbing the film; I wonder if he is reading lips, if I should buy him a headset. He seems to be on another planet, not really with me today, an outline.

‘Do you want a coke?’ I ask him.

Christopher looks at me then shakes his head.

‘Nothing else,’ I turn, I tell her.

‘Sorry?’ She is confused.

‘Nothing else,’ I repeat, louder, almost a shout. She nods, takes the drinks from the metal drawer; she does not question me any further.

‘That’ll be five pounds.’ I hand her Matt’s money, as she pulls down the table clipped onto the chair in front and places the drinks before me.

The whisky burns my throat but at least I feel something.

I stare out through the oval window, watching, waiting.

I see the sea, the deep blue sea.

The seatbelt sign goes on.

within minutes the click.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick.

~cl – ick – ing.

of metal is heard.

‘Cabin crew, ten minutes till landing,’ he says but we all hear.

And then, the plane is descending, rocking, bowing, dipping, shaking, swaying.

And then, I see Malta.

I see my Malta.

The island looks so tiny. I look through the small oval window. I see white, grey, green, blue. The natural colours dance before my eyes, they swirl and twirl and blend.

And as the plane dips, the colours form into outlines, then buildings, looking as if they have been carved into rock, into a mountain that never was. A labyrinth of underground, on ground, overground secrets have formed and twisted into an island that breathes dust. An island surrounded in, protected by a rich and powerful blue. I know that there is so much more than the tourist eye can see.

Quickly, the plane bows to my country, the honeypot of the Mediterranean.

And then, the wheels hit tarmac.

Mer ba.

ba.

~welcome.

I am home.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.