Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

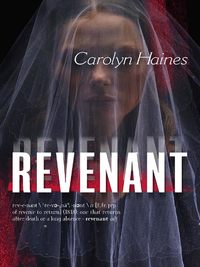

Kitabı oku: «Revenant», sayfa 2

“Four missing girls, all in the summer of 1981, before the parking lot was paved.”

“And the fifth?”

“I don’t know. Maybe she was killed somewhere else and brought to Biloxi.”

“Maybe.” He put a hand on my shoulder. “Mitch wants to see you. He’s waiting in your office.”

I drained the cup. “Thanks.” By the time I made it out of the morgue and into the newsroom, I was walking without wobbling.

3

I studied the back of Mitch Rayburn’s head as I stood in my office doorway. He had thick, dark hair threaded with silver. By my calculation he was in his mid-forties, and he wore his age well. His tailored suit emphasized broad shoulders and a tapered waist. He worked out, and he jogged. I’d seen him around town late in the evenings when I’d be pulling into a bar. He used endorphins, and I used alcohol; we both had our crutches.

“Carson, don’t stand behind me staring,” he said.

“What gave me away?” I asked, walking around him to my desk. He had two things I like in men—a mustache and a compelling voice.

“Opium. It’s a distinctive scent.”

“If I’m ever stalking a D.A., I’ll remember to spray on something less identifiable.”

He stood up and smiled. “I’m ready to go to Angola. Want a ride?”

I shook my head. “I have some leads to work on here, but I’d appreciate an update when you get back.”

“I didn’t realize I was on the newspaper’s payroll.”

I laughed. “How did it go with Brandon?”

“He’s holding the photo, and thanks for not mentioning the missing fingers.”

“You’re welcome. I’m not always the bitch Avery thinks I am.”

“You got off on the wrong foot, and Avery has a long list of grievances with the paper that date back to the Paleozoic era. Give him a chance to know you. He likes Jack Evans.”

I plopped in my chair and motioned him to sit, too. “I went back in the morgue and found four missing girls from the summer of 1981.”

Mitch’s face paled. “I remember…” His voice faded and there was silence for a moment. “I was in law school that year.”

Beating around the bush was a waste of good time. “I read about your brother and his wife. I’m sorry.”

His gaze dropped to his knees. “Jeffrey was my protector. And Alana…she was so beautiful and kind.”

Loss is an open wound. The lightest touch causes intense pain. I understood this and knew not to linger. “I think four of those bodies in the grave belong to the girls who went missing. I just don’t know how the fifth body fits in.” I watched him for a reaction.

“I’d say you’re on the right track, but it would surely be a courtesy to the families if we had time to contact them before they read it in the newspaper.”

Brandon would print the names of the girls if there was even a remote chance I was right. Or even if I wasn’t. I thought of the repercussions. Twenty-odd years wouldn’t dull the pain of losing a child, and to suffer that erroneously would be terrible. “Okay, if you’ll let me know as soon as you get a positive ID on any of them.”

He nodded. “We’re trying to get dental records on two of the girls. There were fillings. And one had a broken leg. Of course, there’s always DNA, but that’s much slower.”

I noticed his use of the word girls. Mitch, too, believed they were the four girls who went missing in 1981 and one unknown body. “Okay, I’ll do the story as five unidentified bodies. Brandon will have my head if he finds out.”

“Not even Avery Boudreaux could torture the information out of me,” he said, rising. “Thanks for your cooperation, Carson.” He stared at me, an expression I couldn’t identify on his face. “I think we’ll work well together. I want that.”

I arched an eyebrow. “Just remember, nothing is free. My cooperation comes with a price. I’ll collect later.”

As soon as he cleared the newsroom, I picked up the phone and called Avery. I told him about the girls, and that I was voluntarily withholding the information for at least twenty-four hours. His astonishment was reward enough. I got a quote about the investigation and began to write the story.

It was after four when Hank finished editing my piece. I left the paper and headed to Camille’s, a bar on stilts that hung over the Sound. The original bar, named the Cross Current, had been destroyed by the tidal surge of Hurricane Camille. The owner had found pieces of his bar all up and down the coast, had collected them and rebuilt, naming the place to commemorate all that was lost in that storm.

The bar was almost empty. I took a seat and ordered a vodka martini. It was good, but Kip over at Lissa’s Lounge made a better one. There had been a bar in Miami, Somoza’s Corpse, that set the standard for martinis. Daniel, my ex-husband, had taught the bartender to make a dirty martini with just a hint of jalapeño that went down smooth and hot. The music had been salsa and rumba. My husband, with his Nicaraguan heritage, had been an excellent dancer. Still was.

A man in shorts with strong, tanned legs sat down next to me. His T-shirt touted Key West, and his weathered face spoke of a life on the water.

“Hi, my name’s George,” he said, an easy smile on his face. “Mind if I sit here?”

I did, but I needed a distraction from myself. “I’m Carson.”

“I run a charter out of here, some fishing, mostly sightseeing.”

I nodded and smiled, wondering how desperate he was. I hadn’t worn a lick of makeup in two years, and sorrow lined my face. I looked in a mirror often enough to know everything that was missing.

“I moved here in 1978, out of the Keys,” he said. “I don’t like the casinos, but they’re a good draw for business.”

“The coast has changed a lot since the casinos came in.” I didn’t want to make small talk, but I also didn’t want to be rude.

He settled in beside me. “I lost the Matilda in ’81. My first boat.”

Storms interested me, and the weather was a safe enough subject. “I was inland then. Was it bad?”

“Deborah hit Gulfport, but we got the worst here in Biloxi. The Matilda was tied up in the harbor. I had at least ten lines on her, plenty to let her ride the storm surge. Didn’t matter. Another boat broke free and rammed her. She took on water and sank right in the harbor.” He shook his head. “She was sweet.”

“I guess you had plenty of warning that the storm was coming. Why didn’t you take her inland?”

“It was a fluke. Deborah hit the Yucatan, lost a lot of power and looked like she was dying out, but she came back strong enough. I really thought the boats could weather it. Never again. I take mine upriver now. I don’t care if it’s a pissin’ rainstorm.”

“Was there much damage?”

“Washed out a section of Highway 90. Took a few of those oak trees.” He shook his head. “That hurt me. Funny, I’ve had a lot of loss in my life, but those trees made me cry.” He sipped his beer. “Life’s not fair, you know. I lost my wife two years ago to cancer. She was my mate, in more ways than one.”

I knew then what had drawn him to me. Loss. It was a law of nature that two losses attract. “My dad’s told me stories of storms that came in unannounced. At least now there’s adequate warning.”

He nodded. “We thought it was petering out. After it hit Mexico, it just drifted, not even a tropical storm. Looked like if it was going anywhere, it’d drift over to the Texas coast. Then, suddenly, it reorganized and roared this way. Caught a young couple on their honeymoon. The storm just caught ’em by surprise.” He looked at me. “Enough doom and gloom. Would you like to go out when I take a charter?” he asked.

To me, boats were floating prisons. I shook my head but forced a smile. “Thank you, but I’m not much for boats or water. I’m afraid you’d regret your invitation.”

“Then how about dinner?”

I hated this. How could I explain that I had no interest in the things that normal people did? “No, thank you.”

He looked into my eyes. “Sometimes it helps to be around other people.”

“Not this time,” I said, putting a twenty on the bar and gathering my purse. “Vodka helps. And sleeping pills.” I walked out before I could see the pity in his eyes.

It was dark outside and I got in my pickup and headed east on Highway 90. The stars in the clear sky were obliterated by mercury-vapor lights and neon. The coast was a smear of red, green, purple, pink, orange, yellow—a hot gas rainbow that blinked and flashed and promised something for nothing.

I drove past the Beau Rivage, the nearly completed Hard Rock casino, the Grand, Casino Magic and the Isle of Capri. Once I was on the Biloxi-Ocean Springs Bridge, I left the glitz behind. Ocean Springs was in another county, one that had refused to succumb to the lure of gambling. My house was on a quiet street, a small cottage surrounded by live oaks, a tall fence and a yard that sloped to a secluded curve of the Mississippi Sound. I’d forgotten to leave a light on, and I fumbled with my keys on the porch. Inside a strident meow let me know that I was in deep trouble.

The door swung open and a white cat with two tabby patches on her back, gray ears and a gray tail glared at me.

“Miss Vesta,” I said, trying to sound suitably contrite. “How was your day?”

A flash of yellow tabby churned out from under a chair and batted Vesta’s tail. She whirled, growling and spitting. So it had been one of those days. Chester, a younger cat, had been up to his tricks.

I went to the sunroom, examined the empty food bowl, replenished it and took a seat on the sofa so both cats could claim a little attention. They were as different in personality as night and day. Annabelle had loved them both, and it was my duty not to fail her. They were the last tangible connection I had to my daughter, except for Bilbo, the pony. Daniel hadn’t even tried to fight me for them when we divorced.

I thought about another drink, but I was pinned down by the cats. Today was Thursday, March 12, Bilbo’s birthday. He was twelve.

I wasn’t prepared for the full blast of the memory that hit. I closed my eyes. Annabelle’s hand tugged at my shirt. “Carrot cake,” she said, grinning, one front tooth missing. “We’ll make Bilbo a carrot cake. And he can wear a hat.” We’d spent the afternoon in the kitchen, baking. I’d made a carrot cake for Annabelle, and a pan of carrots with molasses for icing for Bilbo. Together we’d gone to the barn to celebrate. Daniel had come home early from his import/export business and had met us there, his laughter so warm that it felt like a touch. He’d brought a purple halter, Annabelle’s favorite color, for Bilbo, and it was hidden in a basket of apples.

Chester’s paw slapped my cheek. He was after the tears, chasing them along my skin.

I snapped on a light and got several small balls. The cats had learned to fetch. North of Miami, we’d had twenty acres for them to roam. When I moved to Ocean Springs, I decided to keep them inside, safe.

When the cats tired of the fetch game, I wandered the house. I’d painted the rooms, arranged the furniture, bought throw rugs for the hardwood floors, hung the paintings that I treasured, stored all the family photographs and stocked the pantry with food. It was the emptiest house I’d ever set foot in. When I’d first graduated from college and taken an apartment in Hattiesburg, I’d had a bed, an old trunk, some pillows that I used for chairs, a boom box and some cassettes, but the house had always been full of people.

The fireplace was laid, and I considered lighting it, but it really wasn’t cold, just a little chilly. The phone rang, and I picked it up without checking caller ID. It could only be work.

“Hey, Carson, I wanted to make sure that you’re coming home this weekend. Dad’s got the farrier lined up to do the horses’ feet.”

Dorry, my older sister, was about as subtle as a house falling on me. “I’ll be there. I already told Mom I would.”

There was a pause, in which she didn’t say that I’d become somewhat unreliable. “Today is Bilbo’s birthday,” I finally said. “I forgot.”

“We’ll celebrate Saturday,” she said softly. “He won’t know the difference of a few days.”

Dorry was the perfect daughter. She was everything my mother adored. “The horses need their spring vaccinations, too.” I sought common ground. “I’ll see about it. Dad shouldn’t be out there since he’s on Coumadin.”

“I know,” Dorry agreed. “Mom’s terrified he’ll get cut somewhere on the farm and bleed to death before she finds him.”

My father was the sole pharmacist in Leakesville, Mississippi. The drugstore there still had a soda fountain, and Dad compounded a lot of his own drugs. He was also seventy-one years old and took heart medicine that thinned his blood.

“I’ll take care of the horses. It’s enough that he feeds them every morning.”

“You know Dad. If he didn’t have the farm to fiddle around with, he’d die of boredom, so it’s six of one and half a dozen of the other.”

“Will you and Tommy and the kids be there Saturday?” I was hoping. When Dorry was there, my parents’ focus was on her and her family. She had four perfect children ranging from sixteen to nine. They were all geniuses with impeccable manners. Her husband, Dr. Tommy Prichard, was the catch of the century. Handsome, educated, a doctor who pulled off miracles, Tommy’s surgical skills kept him flying all over the country, but his base was a hospital in Mobile.

“I’ll be there. Tommy’s workload has tripled. He has to be in Mobile Saturday. I think the kids have social commitments.”

I was disappointed. I wanted to see Emily, Dorry’s daughter who was closest in age to Annabelle. “I’m glad you’ll be there.”

“Mom and Dad love you, Carson. They’re just worried.”

I couldn’t count the times Dorry had said that same thing to me. “I love them, too. I try not to worry them.”

“Good, then I’ll see you Saturday.”

The phone buzzed as she broke the connection. I took a sleeping pill and got ready for bed.

4

The ringing telephone dragged me from a medically induced sleep Friday morning. I ignored the noise, but I couldn’t ignore the cat walking on my full bladder. “Chester!” I grabbed him and pulled him against me. “Is someone paying you to torment me?”

He didn’t answer so I picked up the persistent phone and said hello.

“Where in the hell are you?” Brandon Prescott asked.

“In bed.” I knew it would aggravate him further.

“It’s eight o’clock,” Brandon said. “I believe that’s when you’re supposed to be in the office.”

“As I recall,” I answered, my own temper kindling, “when I took the job, we agreed there wouldn’t be rigid hours.”

“I expect you to be on time occasionally. That isn’t the issue. The newspaper has been swamped by families calling in, wondering if the unidentified bodies are someone they know. We need a follow-up story.”

In an effort to spare four families, I’d worried a lot of others.

Brandon continued. “I want you to go to Angola and talk to Alvin Orley. He might have an idea who the bodies are.”

“Mitch went yesterday. I’ll call him and do an interview.”

“He’s the D.A., Carson. That means he doesn’t want us to know what he found out.”

I gritted my teeth and said nothing.

“Besides, even if you get the same information, we can put it in a story. Quoting Rayburn about what Orley said diminishes the power. And the Orley interview will open the door for Jack to do a roundup of a lot of the old Dixie Mafia stories. It’ll be great. So head over to Angola. I got you a one-o’clock appointment with Orley. You can call in and dictate your story.”

I hung up and rolled out of bed. Hank would be righteously pissed off. Brandon was the publisher, but most of the time he acted like the executive, managing and city editor. He meted out assignments and orders, totally ignoring the men he’d hired to do the job. I called Hank at the desk and let him know where Brandon was sending me.

“I’ll call whenever I have something,” I told him.

“Jack’s already working on the old Mafia stories.” Hank’s voice held disgust. “Never miss a chance to drag up clichéd images from the past. We’re running an exceptional tabloid here.”

I made some coffee, dressed, ate some toast and headed down I-10 West toward New Orleans. Before I reached Slidell, I took I-12 up to Baton Rouge and then a two-lane north to St. Francisville and the prison.

Alvin Orley was serving twenty-five years on a murder charge in the slaying of Rocco Richaleux, the mayor of Biloxi at the time. Alvin didn’t actually pull the trigger, but he hired someone to do the job. He and Rocco had once been business partners in the Gold Rush and a number of other establishments that specialized in scantily clad women, booze, dope and gambling. Rocco’s political ambitions ended his affiliation with Alvin, and once elected, Rocco decided to clean up the coast, which meant his old buddy Alvin. Rocco ended up dead, and Alvin ended up doing time in Angola because the murder was carried out in New Orleans. It was a good thing, too. A jury of his peers in Biloxi might not have convicted him. Alvin had ties that went back to the bedrock roots of the Gulf Coast. And he was known to even a score.

Angola was at the end of a long, lonely road that wound through the Tunica Hills, a landscape of deep ravines that bordered the prison on three sides. Men had been known to step off into a hidden ravine and fall thirty feet. The steep hills were formed by an earthquake that created the current path of the Mississippi River, which was the fourth boundary of the prison. During its most notorious days, Angola was a playground for men of small intelligence and large cruelty. Inmates were released so that officers on horseback could chase them with bloodhounds. Manhunt was an apt description. But times had changed at Angola. It was now no better or worse than any other maximum-security prison.

I stopped at the gate. Angola was a series of single-story buildings. Decorative coils of concertina wire topped twelve-foot chain-link fencing. Hopelessness permeated the place. After my credentials were checked, I went inside to the administration building.

Deputy Warden Vance took me into an office where Alvin waited. He’d been in prison since he was convicted in 1983, more than twenty years ago. In the interim he’d lost his hair, his color, his vision and his body. He was a small, round dumpling of a man with a doughy complexion and Coke-bottle glasses. He sat behind a desk piled with papers. Two flies buzzed incessantly around him.

“I’ve read some of your articles in the Miami paper,” he said as I sat down across from him. “I’m flattered that such a star is interested in talking to me.”

“What do you know about the five bodies buried in the parking lot of your club?” I asked.

“Mitch Rayburn asked the same thing. Yesterday. You know I remember giving a check to an organization that helped put Mitch through law school. Isn’t that funny?”

Alvin’s eyes were distorted behind his glasses, giving him an unfocused look. I knew the stories about Alvin. It was said he liked to look at the people he hurt. Rocco was the exception.

“Mitch had a hard time of it, you know,” he continued, as if we were two old neighbors chewing the juicy fat of someone else’s misfortune. “He was just a kid when his folks died. They burned to death.” He watched me closely. “Then his brother drowned. I’d say if that boy didn’t have bad luck, he’d have no luck at all.” He laughed softly.

My impulse was to punch him, to split his pasty lips with his own teeth. “I found the building permits where a room was added to the Gold Rush in October of 1981,” I said instead. “The bodies were there before that. Sometime that summer. Do you remember any digging in the parking lot prior to the paving?”

“Mitch told me that it was the same summer all of those girls went missing,” Alvin said. “He believes those girls were buried in my parking lot after they were killed. Imagine that, those young girls lying dead there all these years.”

“Do you know anything about that?”

“No, I’m sorry to say I don’t. My involvement with girls was generally giving them a job in one of my clubs. It’s hard to get a dead girl to dance.” He laughed louder this time.

“Mr. Orley, I don’t believe that someone managed to get five bodies in the parking lot of your club without you noticing anything.” I tapped my pen on my notebook. “I was led to believe that you aren’t a stupid man.”

“I’m far too smart to let a has-been reporter bait me.” He laced his fingers across his stomach.

“You never noticed that someone had been digging in your parking lot?”

“Ms. Lynch, as I recall, we had to relay the sewage lines that year. Construction equipment everywhere, with the paving. I normally didn’t go to the Gold Rush until eight or nine o’clock in the evening. I left before dawn. I wasn’t in the habit of inspecting my parking lot. I paid off-duty police officers to patrol the lot, see unattended girls to their cars, that kind of thing. I had no reason to concern myself.”

“How would someone bury bodies there without being seen?”

“Back in the ’80s there were trees in the lot. The north portion was mostly a jungle. There was also an old outbuilding where we kept spare chairs and tables. If the bodies were buried on the north side of that, no one would be likely to see them. Mitch didn’t tell me exactly where the bodies were found.”

I wondered why not, but I didn’t volunteer the information. “The killer would have had to go back to that place at least five times. That’s risky.”

Orley shrugged. “Maybe not. On weeknights, things were pretty quiet at the Gold Rush, unless we had some of those girls from New Orleans coming in. Professional dancers, you know. Then—” he nodded, his lower lip protruding “—business was brisk. Especially if we had some of those fancy light-skinned Nigras.”

Alvin Orley made my skin crawl. “Do you remember seeing anyone hanging around the club that summer?”

“Hell, on busy nights there would be two hundred people in there. And if you want strange, just check out cokeheads and speed freaks, mostly little rich boys spending their daddy’s money. The lower-class customers were more interested in weed. If I kept a book of my customers, you’d have some mighty interesting reading.”

He was baiting me. “I’m sure, but since you have no evidence of these transactions, it would merely be gossip. I’m not interested in uncorroborated gossip.”

“But your publisher is.” He wheezed with amusement. “There was a man, now that I think about it. He was one of those Keesler fellows. Military posture, developed arms. He was in the club more than once that summer.”

“Did you ever mention it to the police?”

Orley laughed out loud, his belly and jowls shaking. “You think I just called them up and told them someone suspicious was hanging around in my club, would they please come right on down and investigate?”

Blood rushed into my cheeks. “Do you remember this man’s name?”

“We weren’t formally introduced.”

“I have some photographs of the young ladies who went missing that summer. Would you look at them and see if any are familiar?” I pulled them from my pocket and pushed them across the desk to him.

He stared at them, pointing to Maria Lopez. “Maybe her. Seems like I saw her at the club a time or two. I always had a yen for those hot-blooded spics.” He licked his lips and left a slimy sheen of saliva around his mouth. “Nobody gives head like a Spic.”

“Maria Lopez was sixteen.”

“Maybe her mother should’ve kept a closer eye on her and kept her at home.”

“Any of the others?” I asked.

He looked at them and shook his head. “I can’t really say. Back in the ’80s, the Gold Rush did a lot of business on the weekends. College girls looking for a good time, Back Bay girls looking for a husband, secretaries. They all came for the party.”

I stood up. “Why did you decide to pave the parking lot, Mr. Orley?” I asked.

“It was shell at the time. I was going to reshell it, but the price had gone up so much that I decided just to pave it.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“Be sure and come back, Ms. Lynch. I find your questions very stimulating.”

He was chuckling as I walked out in the hall where a guard was waiting. Alvin Orley’s conversation was troubling. If the parking lot was shell, it would have been obvious that someone had dug in it. Orley wasn’t blind, and he wasn’t stupid.

Once the prison was behind me, I tried to focus on the beauty of the day. Pale light with a greenish cast gave the trees a look of youth and promise. I stopped in St. Francisville for a late lunch at a small restaurant in one of the old plantations. It was a lovely place, surrounded by huge oaks draped with Spanish moss. Sunlight dappled the ground as it filtered through the live oak leaves, and the scent of early wisteria floated on the gentle breeze.

I was seated at one of several tables set up on a glassed-in front porch. I ordered iced tea and a salad. The accents of four women seated at a table beside me were pleasantly Southern. They talked of their husbands and homes. I glanced at them and saw they were about my age, but beautifully made up and dressed with care. Manicured fingernails flicked on expressive hands. Once, I’d polished my nails and streaked my dark blond hair with lighter strands.

“Oh, here comes Cornelia,” one woman exclaimed to a chorus of “Isn’t she lovely?”

I looked out the window and my heart stopped with screeching pain. A young girl with flowing dark hair skipped up the sidewalk. She wore blue jeans and a red shirt. For just one second, I thought it was Annabelle. My brain knew better, but my heart, that foolish organ, believed. I half rose from my chair. My hands reached out to the girl, who hadn’t noticed me.

The women beside me hushed. A fork clattered onto a plate. A woman got up and ran to the door as the young girl entered. She pulled her to her side and steered her away from me as she returned to her table.

I sat down, waited for my lungs to fill again, my heart to beat. When I thought I could walk, I left money on the table and fled.

I drove for a while, trying not to think or feel. At three o’clock I had no choice but to pull over, find a pay phone—because reception was too aggravating on my cell—and dictate my story back to the newspaper. Jack volunteered to take the dictation, and I was glad.

“I’ve got about thirty inches on Alvin Orley’s illegal activities,” he said as he waited for me to think a minute. “I even got an interview with one of his old dancers. She said most all of them had to have sex with him to keep their jobs.”

I gave him my story, the gist of which was that Alvin failed to notice his parking lot was dug up. It wasn’t much of a story, but it would be enough for Brandon.

“Hey, kid, are you okay?” Jack asked.

“Tell me about the fire that killed Mitch’s parents.”

“I forget that you didn’t grow up around here. I guess I remember it so well because at first blush everyone thought it was arson. Harry Rayburn was a prominent local attorney who defended a lot of scum. Everyone jumped to the conclusion that an unhappy client had set the fire.”

“It was an accident?”

“That’s right. Electrical.”

“Both parents died, but the boys escaped?”

“Mitch was just a kid, and he was on a Boy Scout campout. Jeffrey was at baseball camp at Mississippi State University. He was still in high school but scouts were already looking at him. From everything I heard, it was a real tragedy. The Rayburns were sort of a Beaver Cleaver family. Mrs. Rayburn was a stay-at-home mom.” He sighed. “The house went up like a torch.” He hesitated. “Sorry, Carson.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I asked.”

“I covered it for the paper, and I was there when Jeffrey got home from State. He’d picked Mitch up at Camp DeSoto along the way. It broke my heart to see those boys standing by the smoking ruins of what had been their home.”

“You’re positive there was no sign of arson?” I could have read Alvin Orley wrong, but I thought he’d hinted that Mitch’s luck was bad for a reason.

“None. That fire was examined with a fine-tooth comb. It was accidental.”

“I’m headed back to Ocean Springs. Tell Hank to call me on my cell if he needs me.”

“Will do, Carson. Drive carefully.”

I was tempted to get off the interstate at Covington and revisit some of my old haunts. Dorry and I had both shown hunter-jumper. Covington, Louisiana, had hosted some of the finest shows of the local circuit. Dorry had always been the better rider; she rode for the gold. I was more timid, more worried about my horse. I smiled at the full-blown memory of both my admiration for, and my jealousy of, her.

When I went to visit my parents, I’d be able to see Mariah and Hooligan, our two horses, as well as Bilbo, the pony. Both horses were close to thirty now, but they were in good shape. Dad took excellent care of them, and Dorry’s daughter, Emily, groomed and exercised them. She was the only one of Dorry’s children who liked animals, and truthfully, the only one that I felt any kinship with. At twelve, she was only a year older than Annabelle would have been. Had we lived close together, I believed they would have been famous friends.

I checked my watch and stayed on the interstate. I’d spent enough time on memory lane. I needed to get back to Ocean Springs. There were a few loose ends I wanted to tie up before the weekend, and Mitch Rayburn was one of them. He’d promised to call. There was also the matter of the four missing girls. I’d have to run their names in Sunday’s paper, but it would look better for everyone if I could quote Mitch or Avery. I wrote leads in my head as I sped down the highway toward home.

Dark had fallen by the time I pulled into my driveway. My headlights illuminated the shells that served as paving. If someone buried even a rabbit under the shells, I’d notice that they’d been disturbed. Much less five human bodies. Alvin Orley was either blind or lying, and I was willing to bet on the latter.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.