Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

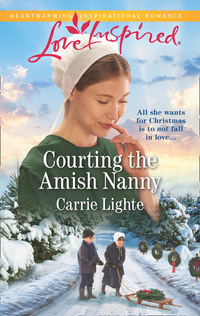

Kitabı oku: «Courting The Amish Nanny», sayfa 2

Maybe she’s widowed, too, he mused but quickly dismissed the idea. There was nothing about her expression suggesting the shadow of grief. Quite the opposite: her eyes were as blue as a cloudless sky and her complexion was just as sunny. If anything, she seemed a bit self-conscious; perhaps because she’d just woken and her hair was loose and mussed from sleep. Even so, her lips were pert with a breezy smile. Vaguely recalling when Leora used to appear as luminous as that, Levi sighed.

“Kumme,” he called to the children and headed to the stable, where the pair of them stayed outside and sat on the stone wall. He required them to keep a safe distance whenever he was hitching or unhitching the horse and buggy. Once finished, he signaled them to approach and they climbed into the back seat so there’d be room for Sadie—who joined them just then—to sit up front with Levi.

“Look at all the pine trees!” she exclaimed as they traversed the long straight road that cut across town. “I could only see their outlines last night. They seem even bigger in the daylight.”

“Don’t you have pine trees where you come from?” Elizabeth asked.

“Not nearly as many as you have here. I’ve never been out of Lancaster County, so it’s fun to see new sights.”

“Later in the week I can take you to the Englisch supermarket,” Levi offered. “The library and post office, too. Since we’re still a young settlement, we don’t have as many Amish businesses as you probably have in Little Springs.”

“Do the Englischers gawk at you when you’re in town?”

“Neh, not at this time of year. Most of them are year-round residents and they’re used to us by now. They’ve been wunderbaar about accepting us into the community but also respecting our differences. Summer is a different story, though, because that’s when tourists kumme to vacation on Serenity Ridge Lake. To them we’re a novelty. Or part of the scenery—I’ve been photographed too many times to count.”

Sadie clicked her tongue sympathetically. Then she pointed to a house. “There’s another one!”

“Another what?”

“A green roof. They’re everywhere.”

“Jah, they’re made of metal,” Levi said, amused by her observation. He’d been here long enough that he didn’t notice the differences between Maine and his home state anymore. “Metal roofing is very popular here because it’s durable and energy efficient. Plus, it keeps ice dams from forming, which is important during our harsh winters. One of our district members, Colin Blank, owns a metal roofing company and he can hardly keep up with the demand.”

Sadie nodded, clearly taking it all in. She was quiet until they turned onto the dirt road and Levi announced their destination was at the top of the hill. “What a strange-looking haus,” she remarked. “Who lives here?”

“No one.” Levi chuckled. Her bewilderment was winsome. “It’s a church building.”

“You worship in a building instead of a home?” Sadie asked so incredulously it sounded as if she was accusing them of something scandalous.

“Jah. The settlement in Unity does, too. It’s a rarity, but it makes sense for us since we’re so spread out and this is the most central location.”

“Wow. Is there anything else I should know about Amish life in Maine?”

“Hmm... Well, on Thanksgiving we eat smoked moose instead of turkey,” Levi teased.

Sadie’s eyebrows shot up. “Really?”

Levi felt guilty about the alarmed look on her face. “Neh. I was only kidding. We have turkey and all the usual fixings.”

“Have you ever encountered a moose?”

“Neh. Fortunately. If they feel threatened, they can be very dangerous creatures.”

“You should always give them lots of space,” Elizabeth advised from the back seat.

“And never get in between a mamm moose and its calf,” David warned. “Because the mamm might charge.”

“I’ll remember that,” Sadie said. “Although I’m a pretty fast runner, so if it charged it would probably moose me.”

David and Elizabeth cracked up, but Levi had to bite his tongue to keep from telling Sadie it wasn’t a joking matter. He hoped she wasn’t going to be glib about the rules he had for the children’s safety or reckless about their care, the way the other nannies had been. Overbearing, one of them had called him in response to his reminders. But what did she know about the responsibilities involved in raising children? She was practically a child herself.

At least Sadie’s older than the other meed were, he thought. But older didn’t necessarily mean wiser. Suddenly, he was struck by a worrisome thought: Why had someone Sadie’s age traveled all this way to take a job usually reserved for teenage girls? She’d been so highly recommended by his uncle that Levi hadn’t thought to ask why she was willing to come to Maine—during Christmas season, no less! Levi was only distantly related to Cevilla, so it wasn’t as if Sadie was fulfilling a familial obligation. Maybe she couldn’t find employment in Pennsylvania—or worse, she’d had a job but was fired.

The other possibilities that occupied Levi’s mind throughout the church service were equally unsettling. As the congregation rose to sing the closing hymn, Levi decided the only way to know if Sadie was a good nanny would be to keep an even closer watch on her than he had on the others. And somehow, he was going to have to accomplish that feat without offending her with his scrutiny.

Dear Lord, give me wisdom and tact, he silently prayed. And if I’ve made a mistake by hiring Sadie, please show me before any harm befalls my precious kinner.

Chapter Two

Although there were fewer families present and church was held in a building instead of a house—and although half of the men wearing beards also wore mustaches—the worship service in Serenity Ridge was very similar to the services Sadie was accustomed to in Little Springs and she felt right at home. Especially because afterward the women greeted her warmly as she helped them prepare the standard after-church lunch of peanut butter, bread, cold cuts, cheese, pickled beets and chowchow in the little kitchen in the basement.

A svelte, energetic blonde woman about five or six years older than Sadie introduced herself as Maria Beiler, one of Levi’s seasonal employees. She said she’d be making wreaths and working the cash register at the farm. “It’s so gut of you to kumme all the way from Pennsylvania. I don’t know what Levi would have done if you hadn’t arrived to watch the kinner.”

“I suppose it’s difficult to find a nanny in such a small district,” Sadie replied modestly.

“Not nearly as difficult as keeping one,” Maria mumbled.

“What do you mean?” Sadie asked, but Maria had whisked a basket of bread from the counter and was already on her way to the gathering room. Her curiosity piqued, Sadie wondered what could be so difficult about retaining a nanny to mind these children. From what she could tell so far, David and Elizabeth were exceptionally well behaved and sweet, if a little timid.

Then it occurred to her Levi might be the one who presented a challenge. He did seem a bit uptight, lacking the sense of humor to laugh at her corny moose joke. But that hardly qualified as a personality flaw and it didn’t overshadow his thoughtfulness in warming up the daadi haus for her or bringing her milk and eggs. Since Sadie knew she wasn’t the best judge of men’s characters, she decided to let Maria’s remark slide. After all, this was a short-term position, and as far as Sadie was concerned, it didn’t matter if the children were incorrigible or Levi was a two-headed monster; she could tolerate anything if it meant avoiding wedding season in Little Springs.

After lunch the women sent Sadie home carrying a canvas bag bulging with plastic containers of leftovers, since she hadn’t been to the supermarket yet and didn’t have anything in her cupboards to snack on. She offered to share the food with Levi and the children at supper, but Levi insisted she enjoy it at leisure by herself. “The Sabbath is a day of rest and you’ve had a long trip. You’ll be preparing meals for us soon enough.”

Although Sadie appreciated his consideration, she wasn’t used to spending Sunday afternoon and evening all alone, and by Monday morning she was so antsy to hear the sound of another person’s voice, she showed up at Levi’s house half an hour early.

“Who is it?” Elizabeth squeaked from the other side of the door.

“It’s me, Sadie,” she answered, wondering who else the child thought could be arriving at that hour. She heard a bolt sliding from its place—in Little Springs, the Amish never locked their houses when they were at home—before the door swung open.

“Guder mariye,” the twins said in unison.

“Guder mariye,” Sadie replied as she made her way into the mudroom. After taking off her coat and shoes and continuing through to the kitchen, she remarked, “Look at you, both dressed already. Have you eaten breakfast, too?”

“Neh, Daed said if we waited maybe you’d make us oatmeal ’cause when he makes it it’s as thick as cement.”

Sadie laughed. “I’m happy to make oatmeal. But where is your daed? Out milking the cow?”

“Neh,” Levi answered as he entered the room. His face was rosy as if it had been freshly scrubbed, and Sadie noticed droplets of water sparkling from the corners of his mustache. She quickly refocused to meet his eyes. He added, “I wouldn’t leave the kinner here alone. I hope you wouldn’t, either.”

Sadie was puzzled. Most Amish children Elizabeth and David’s age could be trusted to behave if their parents momentarily stepped outside to milk the cow or hang the laundry. What was it about the twins that gave Levi pause about leaving them unsupervised? If Sadie didn’t figure it out by herself soon, she’d ask him later in private. “Of course I wouldn’t. We’ll stick together like glue.” Then she jested, “Or like cement.”

Levi cocked his head when the children giggled. Then he got it. “Aha, my kinner must have told you about my cooking.” Laughing at his own expense, he proved he wasn’t humorless after all.

“Cooking is my responsibility now,” Sadie said, since she’d agreed to make meals for the Swarey family. She was invited to eat with them as a perk, in addition to her salary. “I’ll have breakfast ready by the time you return from the barn. Maybe Elizabeth wants to help me make it.”

Elizabeth’s eyes glistened. “Jah—” she said before Levi cut her off.

“Neh, she’s too young to operate the stove. She can kumme with David and me to the barn.”

Seeing Elizabeth’s shoulders sag, Sadie opened her mouth to inform Levi she had no intention of allowing Elizabeth turn on the gas, but that didn’t mean the girl couldn’t assist in the kitchen. Then she figured Levi knew more about his daughter’s abilities than Sadie, so she helped Elizabeth into her coat, hat and mittens while Levi did the same for David.

By the time the trio returned from milking the cow and collecting eggs, breakfast was on the table. In between swallowing spoonfuls of oatmeal, Levi explained, “Even though it’s only the sixteenth of November, we’re harvesting the first trees this week so we can ship them to our Englisch vendors who open their lots the day after Thanksgiving. I’ve also got a few dozen customers who ordered early deliveries of oversize trees for their places of business. You know, local restaurants and shops. A dentist’s office. A couple of churches, too.”

Sadie appreciated hearing about his job. She’d grown up on a farm, but they primarily grew corn and wheat; she had no idea what was involved in harvesting Christmas trees. “How many people do you have on your crew besides Maria Beiler?”

“This week it’s me and four young men from our district. Plus two Englisch truck drivers, who will help bale and load, too. After Thanksgiving we’ll have fewer deliveries. For the most part customers will cut and carry the trees themselves, or else we’ll bag and burlap the live ones, so I’ll reassign staff to manage all of that,” Levi said. He stopped to guzzle down the rest of his juice. “Which reminds me, my brother-in-law, Otto, will be arriving the Saturday after Thanksgiving to help. I hope you don’t mind cooking for him, too?”

“That’s fine. I’m used to preparing meals for a group of hungerich men—I have seven brieder,” Sadie said before asking what made him decide to grow Christmas trees. It seemed an odd choice of crops, considering most Amish people didn’t allow Christmas trees in their own houses.

“The Englischer who sold us the acreage had already planted the seedlings about three years before we arrived. Then his parents had some health issues, so he relocated to Portland to care for them. My wife and I originally planned to clear the land and grow potatoes, but the previous owner had already invested so much into the trees we ended up changing our minds. All told, it’s taken over ten years for the trees to be ready to sell. In the meantime, I’ve also been working for Colin—the man I told you about—who owns a roofing company, so I’d have a steady income until we could turn a profit.”

“Did you live on a farm in Indiana, too?”

“Neh. I worked construction. In fact, that’s why Leora—my wife... That’s why she wanted to move to Maine in the first place. We couldn’t afford to buy farmland in Indiana and it was her dream to raise our kinner in the countryside...” Levi’s voice wavered and he dragged a napkin across his mouth.

Sadie regretted that she’d stirred a painful memory and tried to console him. “I’m sure your wife would be pleased you’re fulfilling her dream for the kinner.” But her comment seemed to upset Levi even more.

He pushed his chair from the table and scowled. “I’ve got a busy day ahead of me, so I don’t have time for any more chitchat.”

Embarrassed by his brusque dismissal, Sadie rose to her feet, too. “Then I won’t keep you. I’m sure the kinner know what their chores are and can help me find whatever I need in the house, although we’ll probably spend time outdoors, too.”

“Neh, I don’t want you taking Elizabeth and David outside.”

Sadie was baffled as to why Levi expected them to stay inside; the weather was cloudy and cold, but she’d take care to dress them warmly. Were they recovering from a recent illness and in need of rest? Or perhaps a wild animal had been roaming the property and Levi didn’t want to frighten the children by mentioning it in front of them. While their father was donning his outerwear, Sadie directed David and Elizabeth to go upstairs and make their beds so she could ask Levi in private why they weren’t allowed outside.

He answered, “There will be trucks on-site today and I don’t want them running along the driveway or even playing in the yard until I’ve had a chance to show you around the property. I need to point out places to avoid. There’s a shallow little pond at the bottom of the hill on the opposite side of the barn, for example.”

Puzzled, Sadie quipped, “I wasn’t planning to take them swimming. Not in this weather anyway.” But when Levi glowered and pushed his hat onto his head, she cleared her throat and added, “We’ll stay on this side of the driveway and keep far away from the trucks, I promise.”

“I said I didn’t want them going outside yet!” he snapped. “Those are my rules for my kinner and if you have a problem following them, perhaps you made a mistake by coming here.”

Sadie saw red. I’m not the one who has a problem, she thought, but she didn’t say it. She had already quit one job impetuously; she wasn’t going to quit this one, too. At least, not without considering it carefully. The thought of sitting through Harrison’s wedding made her wince, but she wasn’t sure she could work for someone as unreasonable as Levi, either.

“You’re right. Perhaps I did make a mistake by coming here,” she replied evenly. “I’ll have to give it more thought.”

Levi pulled his chin back as if surprised. “You do that, then,” he said. “But before I go, I’d like you to look this over. It lists what’s expected of David and Elizabeth, as well as what they’re not allowed to do.”

He went and retrieved a sheet of paper from on top of the fridge and handed it to Sadie and then looked over her shoulder as she read it. The children are not allowed to get too close to the woodstove. The children cannot handle knives. They mustn’t climb on furniture. The list continued on and on. Scanning it, Sadie doubted even the least experienced nanny would need such detailed guidelines to care for Elizabeth and David. Nor did she consider all the rules to be necessary, but she held her tongue.

“Any questions?” he asked when she glanced up.

“Neh, no questions.”

“Gut. I’ll stop by in an hour or two.”

If he’s so pressed for time, why would he bother coming back in an hour? “Oh, there’s no need to disrupt your work,” Sadie suggested. “We’ll be fine until you return for lunch. When would you like to eat?”

“One o’clock,” he replied so gruffly it confirmed Sadie’s suspicion he was the reason the other nannies had quit.

Before leaving the house, Levi called David and Elizabeth back downstairs. He placed a hand on each of his children’s heads, the way he always did before he left them for a length of time. After silently praying for their safety, he removed his hands and gave them each a kiss on the cheek. “Ich leibe dich,” he said and the twins told him they loved him, too.

On the porch he pushed his fingers into his gloves. Although the worst of his grief had subsided over the years, talking about Leora’s dream to live on a farm had brought up sorrowful emotions. Levi regretted she didn’t live to see the tree harvest finally coming to fruition. His wife believed farming was doing God’s work and she envisioned the two of them as pioneers, setting out for Maine on their own. Even though she missed Indiana and her family and experienced terrible morning sickness with the twins, Leora had never complained because she said their move was going to be worth it.

Levi knew she would have been devastated he and the children were leaving Maine. But what else could he do? He’d already lost two nannies from his district, one from nearby Unity and one from Smyrna, in the northern part of the state, who had been visiting her cousins in Serenity Ridge. He doubted there were any other Amish nannies he’d find remotely suitable left in Maine, and if Sadie was any indication, Pennsylvania wasn’t that promising, either.

Judging from the conversation he’d just had with her, she wasn’t going to work out. Which was disappointing—Elizabeth and David had taken an instant liking to her; in contrast with the other nannies, Sadie had shown a genuine interest in them, too. Levi had prayed for guidance. If Sadie refused to honor his instructions or chose to quit, that was as much clarity as he could ask for in regard to whether he’d made a mistake by hiring her. And when it came to his children’s well-being, it was better to know sooner rather than later if she was a suitable match.

The sound of a truck clattering up the gravel road jarred Levi from his thoughts. Signaling the driver, Scott, to stop, he crossed the lawn to the barn, which was located on the opposite side of his house from the daadi haus. Halfway in between his house and the barn was a small workshop. Last week he’d rearranged his tools and workbenches to create an area where Maria could make wreaths. Beginning the day after Thanksgiving, the workshop would also serve as a place for her to ring up sales when the farm opened to the public. But Levi didn’t expect Maria to arrive until nine o’clock, so he continued toward the barn, where he stored the portable baler, the machine used to shake the needles from the trees and the chain and handsaws.

By the time he and Scott loaded the equipment onto the truck bed, the rest of the crew had arrived. Levi spent the next couple of hours explaining the tagging system, showing the young men around the sixteen-acre farm, and demonstrating how to operate the machinery and palletize the trees for shipment, the way he’d learned from working at a tree farm the previous year. The guys groaned when he reminded them they were required to wear goggles and ear protection whenever they used the chain saws, so he delivered a stern lecture on injury prevention.

He intended to supervise their work until he was confident they knew what they were doing and would do it safely, but Walker Huyard, a young Amish man who was employed by a tree service company during the warmer months, pulled him aside. “A word to the wise is sufficient,” he said. “You’ve got an experienced crew here.”

“What do you mean?”

Walker returned his question with a question. “Does Colin Blank watch you like a hawk or nag you like a schoolmarm when you’re roofing for him?”

Levi got his point; on occasion Colin was overbearing, much to the consternation of his employees. Clapping Walker on the shoulder, he said, “You’re right. I’ll leave you guys to it. I’m going to take a break and I’ll be back by ten thirty—to help, not to harp on you.”

He returned to the house to discover the kitchen empty, but laughter spilled from the living room, where Elizabeth and David snuggled against Sadie on the sofa. They were so enraptured by whatever she was saying they didn’t immediately notice his arrival. I don’t know if the kinner could handle the upheaval of another nanny leaving. Especially not Sadie. More to the point, he had no idea who he’d get for a replacement.

Pausing silently at the threshold of the room, he studied her animated gestures; something about the artful way she moved her hands reminded him of Leora and he realized his wife had been Sadie’s age when her life was cut short.

Sadie suddenly noticed his presence. “Can I help you?” she asked dryly.

“Neh, I’m just checking up on you.” That sounded wrong. “I mean, checking in on you. To make sure there’s nothing you need, that is.”

“Denki, we’re all set.” Her tone remained politely formal.

“Sadie’s telling us stories about her brieder,” Elizabeth said.

“One time they used a pulley and a clothesline to fly from the loft of the barn to a tree on the other side of the fence!” David exclaimed.

“Her bruder Joseph got stuck halfway across and he was too scared to let go, so Sadie’s other brieder had to reel him back like a fish,” Elizabeth recited.

Despite his intention to smooth things over with Sadie, Levi had been cautioning his children for so long it was second nature to him to blurt out, “That sounds very dangerous. I imagine they gave Sadie’s mamm and daed a fright and they probably received a harsh punishment.”

“Neh, my eldre didn’t find out until afterward, when it was clear Joseph was okay. My daed was impressed by the ingenuity and durability of their invention. Besides, we positioned our trampoline near the end of the line so we could let go before we hit the tree. It was a lot safer than jumping out of the loft into a pile of straw the way we usually did,” Sadie said with a laugh.

“Her brieder were afraid to try it, but Sadie went first and then they all wanted a turn,” Elizabeth interjected.

Levi pointed his finger at his daughter. “If I ever saw you dangling from a rope in the air, I’d be very, very upset.” As Elizabeth’s expression changed from jubilant to ashamed, Levi realized how punitive he must have sounded, when what he meant to express was how disturbed he’d be if she was ever in such a dangerous position. Trying to assure his daughter she wasn’t being scolded, he said, “But I don’t have to worry about that because you’re not a tomboy.”

“Not yet, she isn’t,” Sadie countered. “She’s too young to determine what kind of personality or interests she’ll develop. But just because she’s a maedel doesn’t mean she shouldn’t run and climb and jump and explore the outdoors. Physical exercise is gut for children, both buwe and meed.”

As Sadie spoke, her eyes flashed a warning Levi was walking on thin ice. “I only meant it would have alarmed me if Elizabeth—or David, for that matter—had gotten stuck the way Joseph did. I didn’t mean there’s anything wrong with a girl being active,” he tried to explain. “My Leora was one of the most adventurous women I’ve ever known. I’ll be pleased if Elizabeth takes after her mamm in that way—but that’ll be when she’s older and can judge for herself whether or not a risk is worth taking. Until then, she needs the guidance of responsible adults.”

Sadie didn’t look at all appeased. She blinked twice before freeing her arms from the children’s grasp and standing up. “You mentioned how much work you have to get done today, so you probably want to return to it now. And I need to begin preparing lunch.”

I’m still on thin ice, Levi thought. Not wanting to push her, he figured he could go back to reminding the children about their safety rules tonight. Right now he sensed if he didn’t back off, Sadie would decide to pack her bags that evening. “Don’t worry about tidying the kitchen or making hot meals for lunch. Sandwiches are fine. The most important thing is the kinner are well cared for. And you’re right, a little exercise is gut for them. If the rain lets up, maybe you can take them for a walk to the barn and back.”

Did he imagine it or did Sadie roll her eyes before glancing at David and Elizabeth and asking, “What do you think, kinner? Can you make it all the way to the barn and back?”

Unsure if she was teasing the children or taking a swipe at him, Levi joked, “If they can’t, I’ll swing by on the clothesline and pick them up.”

The children laughed, but Sadie’s expression remained unreadable. “I’ll see you at lunchtime, then,” he muttered awkwardly, exiting the house as quickly as his feet could carry him.

If Levi thought his comment about sandwiches being acceptable to him or his concession in allowing her to take the children outside was going to win Sadie over, he had another think coming. If the rain lets up? It’s barely drizzling, Sadie fumed as she squared the potatoes for stew. She’d never encountered an Amish father—especially one who lived on a farm—who didn’t fully expect his children to play and do their chores outside in weather far worse than this. Was this one of the differences between the Amish in Maine and the Amish in Pennsylvania, or was it simply one of Levi’s quirks?

And what exactly did he mean about Elizabeth not being a tomboy? Sadie resented the word that had often been used to describe her, too. Which wasn’t to say she didn’t relish being every bit as agile, strong and intrepid as her brothers. But like the word pal, the word tomboy had negative connotations when a man used it to describe a woman. To Sadie it indicated he thought she didn’t also have the feminine interests and qualities that men admired and appreciated in a woman.

She covered the pot and set it on the stove to simmer. “What do I care what Levi thinks of me as a woman anyway?” she muttered. She wasn’t even sure if she was going to stay there.

“Who are you talking to?” David was suddenly at her elbow.

“Oh, sometimes I think out loud,” she admitted. “So, what did you and your schweschder usually do with your groossmammi in the mornings once your chores were done?”

“Groossmammi read to us.”

“Or we played board games or colored,” Elizabeth piped up as she entered the room.

“I see,” Sadie said. She wondered whether their sedentary activities were because their grandmother had been ill and didn’t have a lot of energy, or because of Levi’s restrictions. “The sun is peeking out from the clouds, so let’s take that walk to the barn now.”

The children scurried to the mudroom, where Sadie helped them into their boots, coats, mittens and hats. As soon as they stepped outside, Elizabeth and David simultaneously slid their hands into Sadie’s. Although she was happy to receive the gesture as a sign of affection, she was surprised they didn’t want to run freely, the way most children did after being cooped indoors for any length of time.

“Let’s make a dash for it!” she urged and began sprinting across the yard toward the barn. But the children couldn’t keep up and she didn’t want to tug too hard on their arms, so she slowed to a casual stroll. As they approached the workshop she noticed a lamp burning and asked the children if they thought their father was inside. If I see him again right now, I might not be able to censor myself.

David answered, “Neh, that’s where Maria Beiler makes wreaths.”

Another woman to talk to; that was just what Sadie needed at the moment to take the edge off her unpleasant interaction with Levi. “Let’s stop in and say hello.” As soon as she opened the door, the scent of balsam filled her nostrils.

“What a wunderbaar surprise—wilkom!” Maria greeted them. “Would you like a demonstration of my one-woman wreath-making workshop in action?”

She proceeded to show them how she collected boughs from the bin the crew had filled outside the door. Then she cut the trimmings into a suitable size and arranged them neatly around a specially designed wire ring. Using a foot-pedaled machine, she clamped the prongs on the ring, securing the boughs into place. Finally, she fastened a bright red or gold ribbon on the wreath and then carefully hung it from a peg on a large portable rack.

“As you can see, I’m running out of bows,” she said. “I like to make them at home ahead of time but since yesterday was the Sabbath, I’m falling behind.”

“I can tie a few bows into shape so you can keep assembling the other parts,” Sadie volunteered.

“Denki, but this is my job. You’ve got your hands full enough yourself.”

“Please,” Sadie pleaded.

Maria smiled knowingly. “Do you have a case of cabin fever already?” she asked. Without waiting for an answer, she handed Sadie a spool of ribbon, and to the children’s delight, she announced she needed their help on a special project. She supplied them with precut lengths of red and green cord, as well as a glue stick to share, before leading them to a crate filled with thin slices of tree trunks. She explained how to glue the cord onto the trunk slices, transforming them into ornaments the customers’ children could take for free to decorate their trees at home.