Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Skin Deep»

Copyright

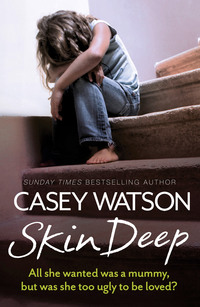

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperElement 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Casey Watson 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover photograph © Cultura Limited/SuperStock (posed by model)

Casey Watson asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780007595099

Ebook Edition © October 2015 ISBN: 9780007595105

Version: 2016-10-19

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Epilogue

Topics for reading-group discussion

If you like this, you’ll love …

Casey Watson

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Write for Us

About the Publisher

Dedication

To me, all children are beautiful. I often liken us parents and carers to gardeners. We work with what we are blessed with, and so long as we nurture and tend to our seedlings, and as long as we sort out what lies beneath – the tangled roots and weeds that threaten to prevent growth – then we can produce strong, healthy plants; some beautiful flowers, others not so aesthetic, but each with a purpose, and set to flourish and go on to create other life. This is all we can do, and all we need to do.

Acknowledgements

As ever, I’d like to thank the team I’m so privileged to work with. Huge thanks to everyone at HarperCollins, my agent Andrew Lownie and, of course, my lovely friend Lynne.

Chapter 1

The long school summer holidays. Who’d have them? We were only three weeks into them, so not even quite at the halfway point, but already that thought was uppermost on my mind several times a day. It was certainly the number one thing on my mind as I attacked the washing up and surveyed the scene of devastation that was supposed to be my garden.

More to the point, why had I always been such a staunch advocate for them? Silly me, I thought ruefully – that one was pretty obvious. It was because I used to work in a school, and those six precious weeks were like a gift from the gods. A vital pause between stints under the tyranny of the school bell. Fickle, fickle, fickle, that was me.

I raised a soapy Marigold and rapped hard on the open kitchen window. ‘Tyler!’ I barked. ‘Denver! Please! Not so rough! And watch my flowers!’ I added hopefully, though without much optimism that either boy would. Though they smiled and waved back at me, they also completely ignored me, chasing each other round the garden with their water blasters just as manically as they had been for the past half hour. My poor windows were going to get it next. I just knew it.

Not that in normal circumstances I’d have much minded the devastation. Tyler had only been with us for a little over a year, but since we’d asked if we could keep him permanently – well, till he was ready to fly the nest – it almost felt like he’d been with us for half his life. And, in truth, I could never be cross with him for long. Well, except when I had to be, obviously. It had been a huge decision and we’d not yet had cause to regret it; now he was in a loving, happy home, he was blossoming.

Which was more than my flowers were being allowed to, however. This was probably par for the course when they were constantly being attacked by an almost 13-year-old boy and his boisterous sidekick. That’s not to say that my flesh and blood family weren’t partly to blame. Riley and Kieron, my own two, had both passed their quarter centuries, but Levi and Jackson – Riley’s boys – were already following enthusiastically in the footsteps of their uncle Kieron, in that, if they saw grass, they immediately thought ‘football’.

Now eight and six, perhaps it was a blessing that they weren’t around to play today, as they were equally skilled at kicking a ball into a rose bush and creating a mud slick out of a previously lush patch of grass. Still, at least Riley and David’s third child had been a daughter, and though my little grand-daughter Marley-Mae was only 16 months old I could already tell she was going to be a proper little lady.

But it was another little lady that was causing me to fuss and flap this morning. I’d had a phone call first thing from my fostering link worker, John Fulshaw, to inform me that he had something of an emergency on his hands – so could I possibly take on a young girl? In typical John style, he was fairly light on facts, operating according to his usual ‘I’ll tell you more when I get there’ routine. So all I knew currently was that she’d been taken into care following a house fire, and that her mother was still in hospital being treated. Oh, and that, like Riley’s Levi, she was just eight years old, and that though her name was Philippa she apparently only answered to ‘Flip’. Oh, and one more thing. That they (as in John, the little girl and the social worker allocated to her) would be arriving at my house in – hell’s bells – less than an hour.

As timings went, it couldn’t have been much worse. I’d already agreed that Tyler’s friend Denver could spend the day with us, which meant I’d had two boisterous almost-teens running wild both in and out of the house all morning, wearing nothing but swimming shorts, splashing around in Marley-Mae’s little paddling pool and generally running amok in that way adolescent boys do, while my house, already messy after a Sunday spent with the very same grandkids, looked like a bomb had hit it.

For a clean-freak like me, this was naturally torture. Or would be, if I’d allowed it to remain in that state, but such was my horror of admitting visitors if it was anything other than pristine, it would be a cold day in hell before I allowed that to happen.

Which meant I needed to crack on fast. I popped the last plate into the drainer and peeled off my washing-up gloves. I’d need my heavy guns to come out for the rest of the chores that I’d be doing, so I went across to my cleaning cupboard to get tooled up: vacuum, duster, disinfectant and mop were my weapons of choice, and every speck of dust, or splash of dirty water, my enemy. The Blitz had nothing on me when I declared war on dirt and mess, and I was just preparing for battle when Tyler splattered into the kitchen, barefoot and grinning, not to mention dripping twin streams of water from the legs of his board shorts to the floor.

‘Any chance of an ice lolly, Casey?’ he wanted to know, accessorising his request with a smile that I knew one day was going to break some hearts in the same way he’d comprehensively stolen mine. ‘Only with all that running about, we’re Hank Marvin!’

I had to smile at that. It had been a term coined by a previous boy we’d fostered, Jenson, who’d learned it, if memory served, from his mother’s latest boyfriend. It had since wormed its way into the family lexicon. It had probably been Kieron who’d passed it on to Tyler, who’d picked it up and run with it ever since.

He shook his dark hair like a shaggy dog would in order to shake off the water, further messing up my already messy floor. ‘For goodness’ sake, Tyler. Stop that!’ I ordered. ‘And an ice lolly is going to stop you feeling hungry, is it? No way, mister. It’s almost lunchtime and I’m going to make a picnic for the pair of you. I’m sure you won’t pass out from malnutrition before then. Now, hop it,’ I added, swivelling him by the shoulders and frog-marching him back outside again. ‘John and the others will be here soon, and I still have lots to do, so how about you and Denver start clearing a space to sit and eat your picnic on, while I do so.’

‘Not even an ice-pop?’ he tried hopefully.

I shook my head. ‘No. Oh, hang on, though,’ I added, reaching across and grabbing the sun spray from the kitchen windowsill. ‘Give each other another good going over with this before you do. You’ve probably washed off half the last lot with those flipping blasters of yours, and I don’t want the pair of you burning. Go on,’ I said, giving it to him. ‘Ice lollies after lunch, promise.’

‘Oh, Casey!’ Tyler grumbled as he took the bottle spray from me. ‘You’re such a fusspot. Look at the label. Look, here – where it says “once”, see? That means we only need it once. That’s why it says it! You’ve already covered us in it about a hundred times!’

‘Covered you with it twice, actually,’ I corrected. ‘And twice never hurt anyone. It says “once” on the paint tins as well, and we all know how well they work, don’t we? Go on, out with you! And put some more on!’ I added, to his departing back.

I was mad, I decided as I surveyed my sopping floor. I was actually mad. Tyler was such a live wire, and had a best friend who was also a live wire, and yet not two hours back I’d gone and agreed to another temporary placement not with trepidation, but with an enthusiastic grin on my face, despite knowing almost nothing about the girl. But then if I was mad, then so was my husband, Mike, because when I’d phoned him at work to double check he was fine about us doing it, he’d agreed to it as well – and in an instant.

‘Well, we said we would, didn’t we?’ he’d pointed out when I asked him if he meant it. These weren’t light decisions to make, after all. But he was right; that had always been the deal. When we’d asked if we could be allowed to keep Tyler, we’d assured John that we’d still be more than happy to foster other kids who might need us – kids who could benefit from going on the specialist behaviour-modification programme we’d been trained to deliver. And this was apparently once such – though for what reason I knew not. But it was a little girl, and she was only eight, so there’d be no extra testosterone wafting around. No, it would be fine. It would work okay with Tyler.

‘So I’ll tell him yes, then,’ I’d said. ‘You know, assuming all seems well once they get here?’

‘Course!’ Mike assured me. ‘You’ve had it easy for long enough, love. Time to get stuck back in.’

Cheeky sod, I thought now. I’d get him back for that later. Perhaps with a well-aimed water blast or two. Right now I had less than an hour – no, nearer 45 minutes – and, if not a mad woman, I was definitely a woman possessed. First impressions worked both ways, after all.

Chapter 2

Like mums everywhere, I always seemed to have several balls in the air at once, so even without the added health and safety risk of my sopping kitchen floor, it was odds on that I’d trip up and lose sight of one. And it seemed I had today. It was only because I was dusting the elderly house phone in the hall that I realised that, in my haste to get things ready for my unexpected visitors, I’d almost forgotten my poor son’s daily ‘un-alarm’ call.

I checked the time, took an executive decision and went to find my mobile. If I didn’t do it now, who knew when I’d next have the chance? And then there might be hell to pay. Keiron had – has – a mild form of what used to be known as Asperger’s syndrome and which is now more commonly referred to as an ASD, or autism spectrum disorder. In an ideal world, I hoped that word ‘disorder’ might soon be changed to ‘difference’, but in the meantime it did mean certain challenges for him, so I supposed it was partly correct. It was something we were all used to, however, and if you met him you’d probably barely even notice it, but the management of it had been a big part of his childhood and even now, though he lived a full and fulfilling life, it still impacted on him in myriad little ways.

He and his long-term girlfriend Lauren were on holiday in Cyprus, which was something of a milestone for them both. As anyone familiar with autism knows, even in its mildest forms it can cause major anxieties, and often these are centred around routine and change. That was Kieron to a T – loved routine, hated change. And with a passion. So going on a holiday, when he’d been growing up, was a very big deal, and something we only attempted rarely.

It wasn’t surprising, then, that when he’d popped round after work one day and announced they were going to Cyprus, just the two of them, I was shocked, as was Mike. This was a big step. It was the first time they’d been away on their own and they weren’t just going away – they were going abroad!

The holiday had obviously taken a fair bit of arranging, and the strain of it soon began to tell. Though he was a grown man of 26, and was understandably keen to meet the challenge, he was terrifically anxious about how he might cope – or, rather, fail to cope – once he got there. Lauren, bless her, had taken on the mantle of chief organiser, planning it, organising their savings and making all the arrangements. But as the date had loomed we could all tell he was struggling with the thought of it, as he reacted just as he’d done since he was a little boy, by chewing off all the skin around his fingernails. That was always a bad sign. So much so that I’d begun to question the wisdom of going at all.

‘Look, Kieron,’ I said one afternoon, when he’d popped round for tea. ‘If you really don’t want to go to Cyprus, then you don’t have to, you know. A holiday is supposed to be something you do for pleasure, after all. Have you spoken to Lauren about how stressed you are? I know she’ll understand if you don’t feel you can face it.’

But he was having none of it, and my heart really went out to him. ‘I have, and that’s exactly what she says as well. But no, Mum,’ he said, ‘I really, really want to go. If I can crack this once, I’ll have it cracked for ever, then, won’t I? Well, sort of. I’m just – oh, you know what I’m like. I can’t stop thinking about all the things that might go wrong on the journey. What if I get stressed and need to talk to you?’

‘Then call me. Get that Euro-travelling package-thingy they do.’

‘And what if I don’t know where to go at the airport, or what queue to join, and Lauren doesn’t either? What if we accidentally get on the wrong plane?’

I was pretty sure Lauren would have had all of that under control, because she was a brilliant, capable girl, not to mention the fact that air travel was almost like bus travel these days. But I also knew my son and how his anxieties could overtake him; so much so that he’d stopped coming on family holidays at the age of 16, preferring to stay instead with my sister Donna.

No, Kieron just needed to know there was a safety net, that was all. ‘So, like I said,’ I repeated, ‘if Lauren can’t sort it, get your phone out and call me. And, I tell you what. How about I call you from time to time in any case. You know, just to see how you’re doing?’

‘Would you, Mum?’ he asked, and I knew right away that this was what he needed. Better for me to keep in touch with him than for him to de-stress himself by reaching for his mobile to call me every five minutes. Just knowing I’d be popping up on his screen at every stage would probably be enough to keep him on top of his anxiety, but without the added anxiety of feeling Lauren would think he was being silly, even though I knew she wouldn’t. Oh, it was a game, it really was, fathoming it all out.

‘Course I will,’ I said. ‘I’ll be like the BT woman, ringing up with alarm calls. Except they’ll be “un-alarm” calls, because there won’t be any alarms, I’m sure of it, as Lauren will have everything under control. And if anything unexpected does happen, you can call me, like I say. Except nothing will, I promise.’

He looked 100 per cent happier. ‘Thanks, Mum. Just till we’re there and settled and that, anyway.’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘You’re just anxious about the travelling, love, which, trust me, is perfectly normal.’

And my ‘un-alarm’ calls had clearly done the trick. We’d spoken four times on the Saturday, three on the Sunday, and now, when I told him I’d got to go as John was due at any moment, he’d hung up before I’d barely taken the phone from my ear, leaving me secure in the knowledge that they were having a good time, and free to concentrate on my young visitor.

Who seemed to be arriving even as I put my mobile back on its charger. With all the windows open, in order to counteract the sweltering heat, I could hear a car pulling up outside the house even before I saw it. I felt the usual stirring of intrigue. It wasn’t quite excitement; that was the wrong word to use in such a circumstance – this was a child who’d been taken into care as an emergency, after all. But there was still a certain frisson; I’d opened several front doors by now, to several different children, and perhaps because ours was a kind of fostering that often took place at short notice I really had to be unshockable when I pulled it back to greet whoever was standing nervously on our front doorstep.

In this case, however, it was only John. And he didn’t look nervous in the least. Just very hot.

‘Oh,’ I said, looking beyond him towards the car. ‘Are you on your own, then?’

‘Only for a little bit,’ he said. ‘They’ve had to go back. For a forgotten Barbie doll. Shouldn’t be long.’

I ushered him inside. ‘Come on in, then. Do you want a cold glass of something? Or an ice pop?’ I said, grinning. ‘We’re very well stocked with those currently, as you can imagine.’

‘Just a large glass of water,’ he said, loosening his tie, and following me into the kitchen. ‘I’m parched. Like a flipping furnace, my car is, in weather like this.’ He grinned ruefully as he placed a manila folder on my kitchen table. ‘Actually – hmm – under the circumstances, perhaps I’d better rephrase that.’

It took me half a second to work out what he was on about. Of course. The fire. ‘Sorry,’ I said, placing a pint glass of water down beside the files. ‘Bit slow on the uptake there, wasn’t I? Sit down, I’ll’ – I stopped and went over to the window, which was being liberally sprayed with a blast from one of the water guns. ‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, Tyler! Will you STOP that!’ I called out of the window. ‘Sorry, John. Think the heat’s getting to the boys, too. They’re both completely manic.’

John chuckled. ‘Enjoying the holidays, then? Sounds like young Ty is, anyway. Actually I could use that kind of dousing right now.’

‘Be my guest,’ I said, waving an arm towards the door out to the conservatory and garden, before pulling out a chair to sit on myself. ‘Though not till you’ve given me some detail on our new arrival. What’s the lowdown? How’s the mum? Badly burnt?’

John shook his head. ‘Apparently not. She’s still in hospital, but it’s mostly smoke inhalation they’re treating her for. A lucky escape.’

‘And the little girl’s okay?’

‘Yes, absolutely fine. Completely unharmed, which is something of a miracle, by all accounts. The blaze all but gutted the entire house, and the mother was lucky to get out alive. Philippa – Flip – was found quite a bit later, by all accounts, hiding in a wardrobe upstairs. Rescued by the lady next door, it seems, while the fire crew were attending to the mother. I just met her, as it happens – she’s become something of a local hero.’

‘I’m not surprised. How did it start? Do they know?’

‘I’m not sure they know for definite, but the assumption is that the mother fell asleep with a cigarette in her hand. Alcoholic,’ he added, opening his files.

I smiled. John had dropped the word into the conversation as if it was something bland and innocuous, like her hair colour or job description or star sign. As he would, because these were the conversations we tended to have. Ah, I thought. So we were getting to the nub of it now. There had to be something, after all. A child could and often would go into care as the result of a major house fire. If their home was gutted, the parent or parents hospitalised, and with no family or friends to take them, a child would invariably end up in temporary foster care. I imagined the little girl on her way to us was coming from temporary foster care herself; an emergency placement, while social services sorted out what needed to be done in the longer term, be it to keep the child there till the responsible adult was in a position to have them back again or, if they’d been orphaned, to find them adoptive parents.

But in this case they were moving her on to us, which meant it was slightly more complex than that. Mike and I, however, weren’t those regular kinds of foster parents. We were trained to foster children who were tending towards being ‘unfosterable’; our specialist programme was designed to modify the behaviour of the most challenging children in the care system, in order that they could be socialised sufficiently to have a hope of going into mainstream foster care and/or being put up for adoption.

Yes, from time to time we did respite care, to help the fostering agency out, just as Riley and David were doing at the moment, but, generally speaking, if a child needed to come to us there was usually an extra problem, and I already knew, from John’s initial call, that there was a reason why he wanted us to have Flip. And this was apparently it.

Well, half of it. The mother being an alcoholic wasn’t the whole story, I was sure. No, there would have to be some sort of challenge to address with the little girl as well.

‘Ah,’ I said. ‘And?’

‘And she’s a long-standing alcoholic. Well known to social services. As is the daughter, because she has foetal alcohol syndrome. Something you’ve probably –’

At which point he stopped, because there was a rap on the front door.

If I’d finished his sentence correctly, John was right. I had heard of foetal alcohol syndrome (commonly known as FAS), because we’d touched on it in training. ‘Touched’ being the operative word; we’d touched on lots of things in training, but with so many ways in which a child could be damaged by the things life had thrown at them, if we’d done more than touch on most of them we’d still be in training all these years later. So, as I walked to the front door, it was with the usual thing in mind – that what I didn’t know I would now simply learn, on the job, so to speak.

I opened the door, the sun streaming in almost bodily; certainly casting my guests into deep shadow, almost silhouetting them on the step. But not for long, because the little girl stepped straight over the threshold. ‘Hello,’ she said brightly. ‘Do you think I’m ugly, Mummy?’

As first lines went, it was an unusual one, to say the least, but as I smiled down at the dot of a girl who now stood before me, I was more struck by what I saw than what she’d said. She was dressed for the weather, in a flower-sprigged cotton sundress with a shirred bodice, the straps tied in neat bows on her skinny shoulders, but my eyes were immediately drawn upwards, to her face.

I’d clearly absorbed more about her syndrome in training than I’d realised. I took in the small head – which seemed too small, even on her tiny little body, even with her fullish head of wavy dark-blonde hair. I took in the far-apart eyes, the upturned nose and the thin upper lip. It was almost like ticking off boxes on a checklist, and I was surprised how immediately the details of FAS came back to me.

But ugly? No, call me soft, but she definitely wasn’t that. Arresting, unusual, but definitely not ugly. Bless her little heart.

‘No, of course you’re not, sweetheart!’ the young woman with her supplied before I could, as she steered Flip around me so she could step inside herself.

‘There,’ I added, smiling at her. ‘Took the words right out of my mouth. Come on in – Flip, isn’t it?’

The girl nodded. ‘And this is Ellie. She’s my social worker. She’s pretty, isn’t she, Mummy?’

‘She is indeed,’ I said, smiling at the social worker, then gesturing towards the doll in Flip’s hand. ‘And who’s this?’

‘It’s Pink Barbie. We nearly forgetted her.’ She raised her other hand, which was clutched around the handle of a small pink vanity case. Both looked new. And apparently were. ‘She goes with this,’ Flip explained. ‘It’s to keep all her clothes in. I gotted them from Mrs Hardy. As a present.’

‘And we nearly came without her, didn’t we?’ the social worker added. ‘As John no doubt told you. Still, we’re here now. All present and correct. Well, such as we can be.’ She too raised a hand holding a bag; in this case a ‘for life’ one, supplied by a well-known supermarket. ‘This is pretty much it.’

‘And I’m pretty, too,’ Flip reminded her. ‘Mummy said so.’

We went back in the kitchen to find that John had filled the kettle and put it on, and was busy pulling mugs from one of the cupboards.

‘You must have read my mind,’ I said, pulling out a third chair. ‘How about you, Ellie – coffee? And what about you, Flip?’ I added, as the social worker nodded an affirmative. ‘Would you like some juice?’

Flip turned to her Barbie – clearly now a very precious possession, even though she had managed to forget her temporarily along the way. ‘Yes, please,’ she said, having put the doll to her ear. ‘And Pink Barbie says do you have any teeny-weeny cups, Mummy?’

‘I’m sure we can find something just right for her,’ I assured her. Mummy. And three or four times now, I mused, as I rummaged in my ‘teeny-weeny cups’ drawer for something Barbie-sized the doll could sip from. What an unusual prospect this sweet little girl looked like being.

Unusual, interesting and definitely bordering on the profoundly challenging. Or so I was about to find out. First, though, there was the usual raft of paperwork, and, of course, the formal introductions. Ellie turned out to be called Ellie Markham, and had only just been assigned to Flip, as a consequence of her having been transferred from out of our local authority area. Though, thankfully, they’d been prompt in transferring all her notes, I felt for Ellie; guessing at her age, my hunch was that she’d not long been qualified, so she was probably diving straight into the deep end while still a little wet behind the ears.

As she wasn’t in a position to give us much in the way of background, I suggested she and I take Flip outside to meet Tyler and Denver, and that perhaps Tyler could take them on a little tour of the house and garden. It was a job that usually fell to Mike while John and I and the attending social worker dealt with all the forms, but with it having been too short notice for Mike to get away from work, we were having to improvise on that front anyway.

Which was fine; I also thought it would be nice for Tyler to meet Flip with his role in the family clearly evident, i.e. that she could see he was very much one of the family, and would naturally assume a big-brother role while she was with us, for however long that looked like being. We’d already primed him a while back, and with the respite work we’d done since we’d had him I was confident he’d adjust to a new child pretty quickly, just as long as he didn’t feel insecure.

Indeed, he seemed puffed up with pride at being given the responsibility, and it was only Ellie’s insistence that she stay by Flip’s side that meant she wasn’t back with John and me herself. ‘Crossing the Ts and dotting the Is,’ John explained when I returned to the kitchen so we could make as short work as possible of the formalities. ‘She has a tendency to wander, I’m told. No sense of stranger danger either – one of the features of her FAS.’ He patted a pile of papers in a slip case. ‘There’s plenty for you to get your teeth into here.’

‘And this is it, is it?’ I asked him as I retook my place at the table. ‘She’s in the care system now? No likelihood of her being reunited with her mum?’

John shook his head. ‘That’s not the plan. She’s been on the “at risk” register for quite a while now, apparently; there have been repeated attempts to get Mum into alcohol abuse programmes, parenting classes and so on, so this fire’s really just been a line drawn in the sand. It was probably only a matter of time in any case. There’s no home for either of them to go back to now, anyway. They’ve apparently lost everything.’ He pointed to the bag Ellie had parked by the table. ‘That’s all she has; the bits and pieces the respite carers pulled together for her. So she’ll need kitting out …’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.