Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: How Gender Equality Can Save The World!»

ALSO BY CATHERINE MAYER

Charles: The Heart of a King

Amortality: The Perils and Pleasures of Living Agelessly

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Catherine Mayer 2017

Catherine Mayer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9780008191160

‘Comprehensive, wide-ranging and journalistically rigorous. Attack of the 50ft Women is an important and timely book. Buy it for yourself, your husband or partner. Most importantly, buy it for your children.’

Sunday Express

‘If you’re male, and don’t think you need to read this book, that’s your received culture talking, and it isn’t doing you a favour. If you’re male or female, do yourself and the future a favour: read this book.’

William Gibson

‘Barnstorming’

Red

‘An inspiring, revelatory and often hilarious journey to explore the merits of a gender-equal society.’

Glamour

‘Empowering and full of hope, Attack of the 50ft Women made me feel 50ft tall. Glass ceilings beware.’

Sarah Shaffi

‘Compelling and deeply researched… Presents the multiple benefits of a gender-balanced world’

Lisa Randall

‘[Catherine Mayer] occupies a well-informed, fully-engaged middle ground [and] quickly gets to the main issue – endemic exploitation, discrimination, harassment and sexual violence perpetrated by men and boys against (overwhelmingly) women and girls … provid[ing] concise, painful examples of perpetrators’ seeming impunity even when charged for their crimes. [Attack of the 50ft Women] is a weapons store for the battles ahead.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘A tour de force of feminist polemic, forensic research drawing on data from across the globe and some fabulously funny anecdotes.’

Wales Online

To sisters, mine especially.

And in memory of Sara Burns, Sarah Smith, Michael Elliott and Ed Victor.

If we were socially ambisexual, if men and women were completely and genuinely equal in their social roles, equal legally and economically, equal in freedom, in responsibility, and in ‘self esteem’, then society would be a very different thing. What our problems might be, God knows. I only know we would have them. But it seems likely that our central problem would not be the one it is now: the problem of exploitation – exploitation of the woman, of the weak, of the earth.

URSULA LE GUIN

‘Is Gender Necessary?’, The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1976.

Contents

Cover

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Introduction: The Shoulders of Giants

Chapter One: Gate-crashing the club

Chapter Two: Votes for women

Chapter Three: All womankind

Chapter Four: Being a man

Chapter Five: Home economics

Chapter Six: What really shocks me

Chapter Seven: Frozen out

Chapter Eight: This should be everyone’s business

Chapter Nine: Unbelievable

Chapter Ten: Adam and Eve and Apple

Chapter Eleven: Winter wonderland

Chapter Twelve: Equalia welcomes carefree drivers

Acknowledgements

Introduction: The Shoulders of Giants

A COLOSSAL ZOMBIE Scarlett Johansson commandeered London’s red buses a few years ago. She sprawled across the upper deck of a fleet of vehicles, face slack with simulated desire, mouth gaping wide enough to swallow a small terrier, breasts threatening to smother passengers seated in the lower tier.

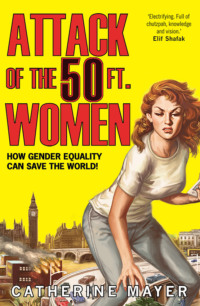

Dolce & Gabbana’s advertising campaign intended to evoke Marilyn Monroe’s heyday, and it succeeded. The apparition recalled Nancy, the title character of a 1958 film, Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman. Nancy’s encounter with a space alien transforms her into a giant (‘Incredibly Huge, with Incredible Desires for Love and Vengeance’). The patriarchal authorities – doctors, police, spouse – chain her, but she breaks free and, naked but for an arrangement of bed sheets, embarks on a murderous rampage. Behold the dreadful power of woman unleashed (‘The Most Grotesque Monstrosity of All’)!

Zombie Johansson captured the inadvertent humour of the B-movie, but she was properly scary too. In her human incarnation she is the only woman to break through Hollywood’s diamond ceiling to claim a place among the ten top-grossing actors of all time. She chooses intelligent roles and has more than once pushed back against the chauvinism of Hollywood and its media ecosystems. Her dead-eyed alter ego belonged to the monstrous regiment of billboard women in perpetual march across the world. Nancy gained agency as she grew. Today’s 50-footers, hypersexualised and supine, promote a retrograde ideology alongside brands and products.

We’re so marinated in this imagery that we seldom stand back to parse its meaning and impact. It is all-pervasive, not just on hoardings and print and broadcast but metastasised into myriad digital forms. The underlying messaging is little different to the drumbeat that helped return women to pliant domesticity after World War II. From earliest childhood, girls are taught to value themselves for their abilities: desirability, marriageability, tractability.

There are, of course, other role models, women of stature and astonishing achievement, but still they break through against the odds. Globally women own less and earn less than men, often in the worst and worst regulated jobs, undertake the lionesses’ share of caregiving and unpaid domestic labour, and are subject to discrimination, harassment and sexual violence.

Every woman navigates a world fashioned by and for men. Some pharmaceuticals fail us because they are tested on male animals to avoid having to account for hormonal cycles. We shiver at our workplaces because thermostats are set to temperatures that suit male metabolisms.

We’re left in the cold in other ways too. On February 6, 1918, the Representation of the People Act gained royal assent, for the first time giving the vote to UK women, if only to those 40 per cent of UK women aged over 30 who met additional criteria such as property ownership. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, a piece of legislation that came into force in November of the same year, meant these 8.4 million voters were not only able to exercise their new right at the December general elections, but in 17 constituencies could vote for Westminster’s first female candidates – returning to office the first female MP, Constance Markievicz. Yet the centenary of these momentous events opened not just with a popping of corks for the progress they enabled, but with a flatulence of punctured hopes. In 2018, the total number of female MPs ever elected surpasses the number of male MPs in the current parliament by only two, and that parliament presides over a country in which to be born female is still a lifelong disadvantage. The Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OECD) logs the gap between women’s earnings and men’s at 17.48 per cent in the UK, and this pattern is echoed across the world, with a gap of 17.91 per cent in the US and 18 per cent in Australia. Women have long been blamed for this gap. We don’t ask for raises often enough or we don’t ask right. Studies identify the real culprits: job segregation and discrimination.

Jobs traditionally performed by men attract higher wages than those held by women. The paradigm of the husband as the head of the household remains firmly lodged in the public imagination. One reason some employers pay men better may be that they think the men have greater need of the money. In the US, men in nursing are vastly outnumbered by their female colleagues, by nine to one, yet earn $5,100 more on average per year than female nurses. These disparities are echoed across the world.

Every woman lives with the constant tinnitus hum of low-level sexism. Most of us have been leered at or leched over and told we should be flattered by the attention. Almost a fifth of US women will be raped in their lifetimes, with close to half reporting other forms of sexual violence. One in three women worldwide will be subjected to violent sexual attack. The response to this epidemic is muted and muddled.

US prosecutors ask a judge to send a college athlete to prison for six years for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman; the judge decides on six months, concerned a longer period of incarceration will have a ‘severe impact’ on the perpetrator, who is then freed halfway through his sentence. In India, a woman is gang-raped to death; one of her rapists says: ‘A decent girl won’t roam around at nine o’clock at night. A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy.’ In Russia, where domestic abuse is thought to kill one woman every 40 minutes, legislators find a way to reduce criminal cases of domestic violence – by decriminalising ‘moderate’ violence and reserving criminal penalties for cases where beatings result in broken bones. The majority of the 276 schoolgirls kidnapped by terrorists in northern Nigeria are still missing; those who escape bearing tales of mass rape and slavery find themselves social outcasts. Egyptian lawmakers finally approve a draft bill that would dole out five-to seven-year jail terms for people carrying out female genital mutilation (FGM), an operation to remove part or all of the clitoris. The procedure – often called circumcision by those trying to minimise its brutality – has been inflicted on more than 90 per cent of the country’s women and girls. ‘We are a population whose men suffer from sexual weakness, which is evident because Egypt is among the biggest consumers of sexual stimulants,’ an MP protests. ‘If we stopped circumcising we will need strong men, and we don’t have those.’ Up to 1,000 women are sexually assaulted on the streets of the German cathedral city of Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015; the attacks trigger condemnation not of women’s oppression but of migration, reinforcing the false narrative that sexual violence is imported, rather than native to white European society. In October 2017, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences votes to expel producer Harvey Weinstein amid allegations by dozens of women of harassment, assault and rape. As details emerge, more women come forward, with stories not only about Weinstein but the entire film industry and then about other industries and, of course, about politics. A UK government minister, Mark Garnier, admits calling his female aide ‘Sugar Tits’ and does not deny sending her to buy sex toys, but blusters that this ‘absolutely does not constitute harassment’. Michael Fallon, Secretary of State for Defence, resigns after admitting he touched a journalist’s knee. Another journalist says he lunged at her. More Conservatives are accused of pawing and worse, but so too are MPs from other parties. Bex Bailey, a Labour activist, reveals that when she told a party official she’d been raped by a senior colleague, the official advised her that to report the assault would ‘damage’ her. This ‘is a problem in every party at every level,’ says Bailey.

Across the world, similar stories come to light. During a debate in the EU Parliament, several female members hold up handwritten signs that say ‘#MeToo’. The backlash starts quickly. This is, powerful men complain, a ‘witch-hunt’, yet the flood of stories shared on Twitter using the #MeToo hashtag are only revealing what women already knew, that sexual violence, threatened or actual, is part of our everyday experience. When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences proclaims an end to ‘the era of wilful ignorance and shameful complicity in sexually predatory behaviour and workplace harassment’, we shake our heads in disbelief. When the President of the United States muses that ‘women are very special. I think it’s a very special time. A lot of things are coming out and I think that’s very, very good for women, and I’m happy a lot of these things are coming out. I’m very happy it’s being exposed’, our jaws hit our chests. Because this is patently untrue.

The previous November, US voters have chosen Donald Trump despite hearing a recording of him boasting of assaulting women. ‘Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything,’ he said. The recording prompted ten women to come forward to accuse him of assault, often in workplace settings. He insisted that they were lying. After all, two of them were too ugly to grope.

Many other aspects of his candidacy should also have repelled any voter who values equality. The candidate appeared to believe only in himself, but pandered to Christian social conservatives by promising to roll back women’s reproductive rights. He pledged to ban Muslims from the country and force Mexico to build a wall to keep its own citizens from crossing the border into the US. He refused to condemn his supporters for racist violence. He publicly invited the Russian secret service to hack US government emails to damage his opponent and announced he would unpick years of international negotiations to limit climate change – which he called a ‘hoax’.

He was, without a shred of doubt, the worst would-be President we had seen in our lifetimes or read about in history books – dangerous, incoherent and vain.

And yet to a significant slice of America, he appeared a better bet than his female challenger.

A majority of men voted for him, by 53 per cent to 41 per cent.

A majority of white people voted for him, by 58 per cent to 37 per cent.

Eighty-one per cent of white evangelicals and born-again Christians voted for him.

Women voted against him, by 54 per cent to 42 per cent. Yet a majority of white women supported him: 53 per cent.

A dual US and UK national, I cast a ballot in my home state of Wisconsin. I am not one of the white women who helped Donald Trump into the White House, but like all white American women, I am implicated. Through researching this book, I also understand the mechanisms that encourage turkeys to vote for Christmas.

This book aims to set out those insights and to make something else abundantly clear. The skewed status quo serves almost nobody – certainly not most men.

The world is full of decent men who strive to be allies to women. It’s a safe bet that most men who are engaged enough in these issues to read these pages fall into this category, though you may not always be sure how best to support us. Many of you want change, for women and girls and for yourselves, but you don’t always understand that ‘women’s issues’ are your issues. You observe your own sex suffering within patriarchal cultures and structures but don’t always join the dots. Because of these structures, boys struggle at school; suicide rates are highest among young males, who are also more likely to murder and more likely to be murdered; and men drink more heavily and more frequently end up in prison. Fathers yearn to be with their children, but the enduring pay gap means they cannot afford to stay home, while social norms sometimes deter them from pushing for change. Businesses, institutions and economies underperform.

The twenty-first century wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Late boomers like me grew up believing history was going our way. We assumed progress to be linear, counting ourselves lucky to be born to an era that had all but vanquished the great scourges of humanity. Racism and homophobia proved susceptible to education and so would wither. Wars were still prosecuted, but at a distance. Hunger, too, seemed confined to far-away lands, and technology must surely deliver fixes, just as it would soon banish cancer, ageing, death and clothes moths. As for women’s rights, the heavy lifting had been done by the women, and their male allies, who came before us. A liberal consensus held sway and growing up in comfort, largely surrounded by the white middle classes, I had no idea of the limits or vulnerabilities of our progress.

After a peripatetic early childhood, I attended a girls’ school in Northern England that proudly counted among its alumnae all three daughters of the magnificent, if flawed, Emmeline Pankhurst. We learned that in 1918, as Europe made its fragile peace, Suffragettes and the more peaceable Suffragists, led by Millicent Fawcett, hailed the beginning of the end of the gender wars as women for the first time voted and ran for parliament. A decade later, all adult females got the vote. New Zealand had led the way in 1893. The US followed suit in 1920. When I was seven and still living in the US, the doughty women of Ford Dagenham fought and won the battle for equal pay. Women’s libbers and the Pill were finishing the job. As teenagers my contemporaries and I saw shimmering on the near horizon a fully gender-equal society in which every inhabitant could stand as tall as the next person.

I named this place ‘Equalia’, and like a querulous child on a family outing, I’ve spent much of my life asking ‘When will we get there?’ There’s always someone prepared to claim we’ve already arrived. Such people rarely describe themselves as feminists because they misunderstand the term as a doctrine of suppression.

The media maintains lists of pundits who can be relied on to declare that Western women already have enough equality. After all, most Western countries have legislated for equal pay, even if the legislation hasn’t achieved the desired result. The laws and their application cannot be faulty; women must be choosing their lower status. Sex discrimination and sexual harassment are outlawed, so women must deserve this treatment. We never had it so good. We should stop whingeing and worry about Saudi Arabia. (It is axiomatic among these useful idiots that you cannot advocate for the rights of women in your own country and in Saudi Arabia.) Feminism can go home and put its feet up.

Broadcasters are particularly fond of pitting women against women. The anti-feminist female is as persistent a breed as the clothes moth. Typically white and middle class, she either doesn’t believe in gender equality or else she doesn’t believe in gender inequality – because she’s too cocooned and myopic to see it. She routinely seeks to strengthen her case by co-opting a tenet of feminism: that the personal is political. She feels no kinship with younger and less privileged women still fighting the old battles while simultaneously picking their way through new and dangerous territories. She declares that she has never experienced sexism or discriminatory behaviour she couldn’t handle. She is thriving.

Let us celebrate the advances that enable her complacency even as we sometimes doubt her sincerity. Her protests are too vigorous, her unease in her own skin too obvious. Her mind has hardened with habit into narrow pathways and she cannot conceive how her own discomfort might relate to a wider pattern. The men around her give succour to her views.

‘The war has been won,’ one such tells me. ‘It’s just a mopping up operation now. You can’t even kick your dog now much less your wife.’ Yet, make no mistake, we haven’t reached Equalia. The Most Grotesque Monstrosity of All? We’re still a long, long way from Equalia.

We live, wherever we live, under a patriarchy, a system that excludes women. Not a single country anywhere on the planet has attained parity. The Nordic quartet of Iceland, Norway, Finland and Sweden tops the rankings of the best places to be female. Even in these countries, though, girls start life as second-class citizens and will be demoted further down the unnatural order with every year beyond their socially determined prime, or if poor or non-white or disabled or daring to combine any of these factors.

There is increasing awareness that gender is not binary but a spectrum, yet this awareness has neither diminished gender conflict nor created acceptance for people transitioning along the spectrum or sitting at junctions that challenge bureaucratic or social labels. Groups that are themselves disadvantaged unconsciously incorporate patriarchal pecking orders. Gay men have a habit of crowding out the other letters in the LGBTQ movement. Civil rights activists have form too. In 1964, Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, batted away a question about women volunteers. ‘The position for women in SNCC is prone,’ he said. It was, he later explained, a joke, but one that closely matched the experience of women in progressive movements. Black Lives Matter, founded by three women: Patrice Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, to illuminate the high – and under-reported – toll of racially motivated killings of black Americans by whites, focuses increasingly on the killings of black males by law enforcement officers. This is hugely important but killings of black women get less attention, prompting a separate movement to take up the cause, #SayHerName.

The elites that might be expected to forge solutions are themselves part of the problem. There is a startling lack of any kind of diversity in politics, and the gender imbalance is stark. Westminster isn’t the only legislature where men dominate, and all political cultures struggle with, and usually succumb to, misogyny. America blew its chance to finally elect a woman to the White House amid barbs about blow jobs. ‘Hillary sucks, but not like Monica’ read T-shirts and badges flaunted by Trump supporters. Bill Clinton, at 49 and President of the United States, did have sexual relations with 22-year old White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Hillary Clinton, like Lewinsky, continues to be vilified for his actions. Sexism and misogyny were by no means the only drivers of her defeat, but they certainly played a part. Still, women had cause to celebrate the elections according to the US media outlets that trumpeted ‘the highest number of women of colour on record’ to win seats in the Senate. That record-breaking grand total equals just four: Catherine Cortez Masto, Tammy Duckworth, Kamala Harris and Mazie Hirono. The number of female representatives in both houses remained static at 104, a mere 19.4 per cent.

Business is just as bad. Among CEOs of the biggest companies in the UK and the US there are more men called John than women of any name. Financial institutions in both countries are overwhelmingly white, male and middle class. Other key institutions – the judiciary, the police, the media – share the same weaknesses.

Here’s something else they share: most of them claim, institutionally and individually, to support gender equality. The liberal consensus is still alive but it is under concerted attack from different expressions of political and religious extremism. The forces ranged against it aim not only to destroy it, but to dismantle its legacy of rights and protections. Progress is not, after all, linear, and it is far too easily reversed.

We would not have so much to lose if not for the achievements of feminism. Its Western incarnation loosely divides into four eras, or waves. The first, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coalesced around the battle for votes for women. The second kindled in the 1960s, and asserted reproductive rights as a tool of liberation that would enable women to define their own being and sexuality and participate alongside men outside the home. It often rejected the possibility of equality within existing systems and structures. A third iteration in the 1990s grappled with the movement’s own failings to address systemic inequalities in its own ranks, while another strand attempted to seize ownership of male ideals of womanhood and recast them as female empowerment. The 1993 remake of Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman, starring Daryl Hannah, becomes a parable of emotional as well as physical growth, and gets a happy ending.

We’re now well into a fourth era, more of a torrent than a wave thanks to the proliferation of digital media, and too fast-flowing to analyse easily. It doesn’t help clarity that so many people lay claim to be part of that flow. Business leaders insist that finding and retaining female talent is essential to success. Economists hail increasing gender balance in the labour force as the key to growth. One recent report estimates a boost to global GDP of £8.3 trillion by 2025 simply by making faster progress towards narrowing the gender gap. Two large-scale pieces of research by Credit Suisse suggest that companies with significant numbers of women in decision-making roles are more profitable. Multiple studies also show that giving women a greater say – and a greater stake – in the planet is essential to building a healthier planet. Trump rushed to withdraw the US from the Paris accord, continuing to voice doubts about the reality of climate change. Among the rural poor, women don’t have the luxury of such doubts. They are at its sharp end, because females are most often tasked with sourcing water, food and energy for their families and communities. In 25 sub-Saharan countries, 71 per cent of the water collectors are women and girls who every day spend an estimated 16 million hours fetching water, compared to six million hours spent by men. The worse the drought, the longer the journeys and the greater the vulnerability of those women and girls. In India, 75 per cent of rural women work in agriculture but own only nine per cent of arable land. Bina Agarwal, Professor of Development Economics and Environment at the University of Manchester, posits that increased female participation in business decision-making improves environmental outcomes.

Agarwal rejects the romantic idea that this is because women are in some way closer to nature than men, but much of the current orthodoxy identifies women as a corrective to testosterone-driven cultures. The Credit Suisse studies find companies steered by women take fewer risks. ‘Where women account for the majority in the top management, the businesses show superior sales growth, high cash-flow returns on investments and lower leverage,’ says the 2016 report.

Politicians of many stripes laud women and profess to fight for us. Congresswoman Ann Wagner went so far during the US election campaign as to call on her own party’s nominee to stand aside because of his misogyny. ‘As a strong and vocal advocate for victims of sex trafficking and assault, I must be true to those survivors and myself and condemn the predatory and reprehensible comments of Donald Trump,’ Wagner said in an October 2016 statement. Less than a week before polling day, she urged voters to back Trump, and has subsequently become an enthusiastic cheerleader for his dismantling of the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. Thirteen male Senators drafted Trump’s first attempt at a replacement bill, which restricted funding for Planned Parenthood and access to abortion insurance, and would have allowed companies providing healthcare insurance to charge women more for ‘pre-existing conditions’. That might sound reasonable until you consider the conditions – pregnancy, Caesarian sections, post-natal depression, domestic violence, sexual assault and rape.

Wagner has been unlucky in one respect. Political commitment to gender equality is often little more than skin deep, but a great many politicians get away without their commitment being so publicly tested and found wanting. This is not to paint all politicians as hypocrites. Many of them believe in women. It’s just that when push comes to shove, they believe in other things more – and they also make the mistake I once did, of assuming that gender equality is already well on its way, without any extra help from them.

If there is a sliver of a silver lining to Trump’s victory, it is that it dented this myth. It did not destroy it. Clinton’s defeat seemed to contrast a regressive US with feminising cultures elsewhere. Patricia Scotland had recently taken office as the Commonwealth’s first female Secretary-General. Estonia had its first female president. Rome and Tokyo for the first time had elected female mayors. After a campaign dominated by male voices tore up the UK’s membership of the European Union and Prime Minister David Cameron stepped down, Britons wondered if women might save the day. Some looked with envy at Germany and its unflappable Chancellor Angela Merkel. More than a few English voters discovered a new reason to beg Scotland not to secede; they wanted the country’s clever First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to be Prime Minister of England too. Britain’s two biggest parties, the governing Conservatives and Labour opposition, turned hopeful eyes to senior women in their ranks. There was, after all, precedent. In 1979, the British economy seemed locked into a downward spiral of a weakening currency and blooming inflation, amid industrial unrest that saw even gravediggers down tools. Then a general election returned Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street, the first female Prime Minister not only of the UK but of any major industrial democracy. Within a few years, her economic policies had laid waste whole communities and sectors but galvanised others and, more than that, revived a sense of potential that had long been missing.