Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «A Baby’s Cry»

Copyright

HarperElement

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

and HarperElement are trademarks of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published by HarperElement 2012

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

A BABY’S CRY. © Cathy Glass 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

ISBN: 9780007442638

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007445707

Version 2018-11-05

Dedication

To Dad with love

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Secretive

Chapter Two

Helping

Chapter Three

Alone in the World

Chapter Four

Bonding

Chapter Five

The Case

Chapter Six

The Mystery Deepens

Chapter Seven

Abandoned

Chapter Eight

Stranger at the Door

Chapter Nine

Section 20

Chapter Ten

Shut in a Cupboard

Chapter Eleven

Ellie

Chapter Twelve

A Demon Exorcized

Chapter Thirteen

Pure Evil

Chapter Fourteen

Shane

Chapter Fifteen

No Wiser

Chapter Sixteen

The Woman in the Street

Chapter Seventeen

Information Sharing

Chapter Eighteen

Staying Safe

Chapter Nineteen

A Right to Cry

Chapter Twenty

An Ideal World

Chapter Twenty-One

Honour

Chapter Twenty-Two

A Baby’s Cry

Chapter Twenty-Three

Late-Night Caller

Chapter Twenty-Four

Harrison

Chapter Twenty-Five

Best Christmas

Chapter Twenty-Six

Little Brother

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Contact

Chapter Twenty-Eight

The Decision

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Letting Go

Chapter Thirty

Upset

Chapter Thirty-One

Goodbye Harrison

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Exclusive sample chapter

Cathy Glass

About the Publisher

Prologue

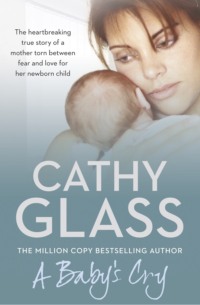

Children can come into foster care at any age and it is always sad, but most heartbreaking of all is when a newborn baby, sometimes only a few hours old, is taken from their mother and brought into care.

Certain details in this story, including names, places, and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

Chapter One

Secretive

‘Could you look after a baby?’ Jill asked.

‘A baby!’ I said, astonished.

‘Yes, you know. You feed one end and change the other and they keep you up all night.’

‘Very funny, Jill,’ I said. Jill was my support social worker from Homefinders, the agency I fostered for. We enjoyed a good working relationship.

‘Actually, it’s not funny, Cathy,’ she said, her voice growing serious. ‘As we speak a baby is being born in the City Hospital. The social services have known for months that it would be coming into care but they haven’t anyone to look after it.’

‘But Jill,’ I exclaimed, ‘it’s years since I’ve looked after a baby, let alone a newborn. Not since Paula was a baby, and she’s five now. I think I might have my pram and cot in the loft but I haven’t any bottles, baby clothes or cot bedding.’

‘You could buy what you need and we’ll reimburse you. Cathy, I know you don’t normally look after babies – we save you for the more challenging children – and I wouldn’t have asked you, but all our baby carers are full. The social worker is desperate.’

I paused and thought. ‘How soon will the baby be leaving hospital?’ I asked, my heart aching at the thought of the mother and baby who were about to be separated.

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow!’

‘Yes. Assuming it’s a normal birth, the social worker wants the baby collected as soon as the doctor has given it the OK.’

I paused and thought some more. I knew my children, Paula (five) and Adrian (nine), would love to foster a baby, but I felt a wave of panic. Babies are very tiny and fragile, and it seemed so long since I’d held a baby, let alone looked after one. Would I instinctively remember what to do: how to hold the baby, sterilize bottles, make up feeds, wind and bath it, etc.?

‘It’s not rocket science,’ Jill said, as though reading my thoughts. ‘Just read the label on the packet.’

‘Babies don’t come with labels, do they?’

Jill laughed. ‘No, I meant on the packet of formula.’

‘Why is the baby coming into care?’ I asked after a moment.

‘I don’t know. I’ll find out more from Cheryl, the social worker, when I call her back to say you can take the baby. Can I do that? Please, Cathy – pretty please if necessary.’

‘All right. But Jill, I’m going to need a lot of advice and …’

‘Thanks. Terrific. I’ll phone Cheryl now and then get back to you. Thanks, Cathy. Speak to you soon.’

And so I found myself standing in my sitting room with the phone in my hand expecting a baby in twenty-four hours.

Panic took hold. What should I do first? I had to go into the loft, find the cot and pram and whatever other baby equipment might be up there, and then make a list of what I needed to buy and go shopping. It was 10.30 a.m. Adrian and Paula were at school. There’s plenty of time to get organized and go shopping, I told myself, so calm down.

First, I went to the cupboard under the stairs and took out the pole to open the loft hatch; then I went upstairs and on to the landing. Extending the pole, I released the loft hatch and slowly lowered the loft ladders. I don’t like going into the loft because I hate spiders and I was sure the loft was a breeding ground for them. I gingerly climbed to the top of the ladders and then tentatively reached in and switched on the light. I scanned the loft for spiders before going in completely.

I spotted the cot and pram straightaway. They were both collapsed and covered with polythene sheeting to protect them from dust; I intended to sell them one day. I also spotted a bouncing cradle. All of these Adrian and Paula had used as babies. Carefully stepping around the other stored items in the loft and ducking to avoid the overhead beams, I kept a watchful eye out for any scurrying in the shadows and crossed to the baby equipment. Removing the polythene I saw they were in good condition and I carried them in their sections to the loft hatch opening and down the ladders; then I stacked them on the landing, to be assembled later. I returned up the ladders and switched off the loft light, and then closed the hatch and took the pole downstairs, where I returned it to the cupboard.

Perching on a breakfast stool in the kitchen I took a pen and paper and began making a list of the essential items I’d need to buy: cot mattress, cot and pram bedding, baby bath, changing mat, bottles and formula milk, first-size clothes, nappies, nappy wipes, baby bath cream, etc. As my list grew, so too did my anticipation and I began to feel a little surge of excitement at the thought of looking after a baby – although I was acutely aware that my gain would be another woman’s loss, as it meant that a mother would shortly be parted from her baby, which is always very very sad.

When the shopping list of baby equipment appeared to be complete and I couldn’t think of anything else, I tucked the list into my handbag, locked the back door and, slipping on my sandals, left the house to drive into town. It was a lovely summer’s day and as I drove my thoughts returned to the mother who was now in labour and whose baby I would shortly be looking after. I knew that taking her baby straight into care from hospital wasn’t a decision the social services would have taken lightly, as families are kept together wherever possible. The social services, therefore, must have had serious concerns for the baby’s safety. Possibly the mother had a history of abuse or neglect towards other children she’d had; maybe she was drink and or drug dependent; possibly she had mental health problems; or maybe she was a teenage mother who was unable to care for her infant. Whatever the reason, I hoped, as I always did with the children I fostered, that the mother would eventually recover and be able to look after her child, or if she was a teenage mother that the necessary support could be put in place to allow mother and child to be reunited.

When you think of the months of planning and the preparation that parents make when they find out they are expecting a baby, it was incredible that an hour after entering Mothercare I was pushing the trolley towards the checkout with all the essential items I would need, plus a few extras: I couldn’t resist the cuddly soft-toy elephant from the ‘baby’s first toys’ display, nor the bibs embroidered with Disney characters and the days of the week, nor the Froggy rattle set. I’d pay for these from my own money while the agency had said they would fund the essentials.

It was 1.15 as I paid at the till and then wheeled the trolley from the store and to the lift in the multistorey car park. I was expecting Jill to phone any time with more details and I had my mobile in my handbag with the volume on loud. Sure enough, as I closed the car boot and was about to get into the car my phone went off. Jill’s office number flashed up and when I answered she said, ‘It’s a boy. He’s called Harrison, and he’s healthy.’

‘Excellent,’ I said. ‘And his mother is well too?’

‘I believe so. Cheryl didn’t say much other than you should be ready to collect him tomorrow afternoon. She will telephone again tomorrow morning with the exact time to collect him.’

‘All right, Jill. I’ll be ready. I’ve just been shopping and I think I’ve got everything.’

‘Good. And Cathy, just to confirm the baby is healthy. There are no issues of him suffering withdrawal from drink or drugs. His mother is not an addict.’

‘Thank goodness,’ I said. ‘That’s a relief.’ For I was aware of the dreadful suffering endured by babies who are born addicted to their mother’s drugs. Once the umbilical cord is cut and the drug is no longer filtering into the baby’s blood they go ‘cold turkey’, just like adults withdrawing from a drug. Only it’s worse for babies because they don’t understand what’s happening to them. They scream in pain from agonizing cramps for hours and can’t be comforted by their carer. They shiver, shake, vomit and even fit, just as an adult addict does. It’s frightening and pitiful to watch, and it often takes many months before the baby is free from withdrawal. ‘Thank goodness,’ I said again.

‘And, Cathy,’ Jill said, her voice growing serious, ‘you need to prepare yourself for the possibility that you might meet Harrison’s mother at the hospital tomorrow. A nurse will be with you, but I thought I should warn you.’

‘Oh, yes, thank you. I hadn’t thought of that. That will be upsetting – poor woman. Do you know anything more about her?’

‘No. I asked Cheryl but she seemed a bit evasive. Secretive almost. I’ll be speaking to her again tomorrow to clarify arrangements for collecting the baby, so I hope I’ll find out more then.’

And that was the first indication of just how unusual this case would be. Jill was right when she said the social worker was being secretive, but it was not for any reason she or I could have possibly guessed.

Chapter Two

Helping

When I arrived home I unloaded all the bags of baby equipment from the boot of the car and then took them upstairs, where I stacked them in the spare bedroom. This was the bedroom I used for fostering and it was rarely empty, for there was always a child to be looked after. However, I’d already decided that baby Harrison wouldn’t be using this bedroom for the first few months but would be sleeping in the cot in my room, as Adrian and Paula had done when they were babies. This was a precautionary measure so that I could check on him and answer his cries immediately. And again my thoughts went sadly to Harrison’s mother, who wouldn’t have the opportunity to hear her baby cry at night or see him chuckle with delight during the day.

Having unloaded the car, I left all my purchases in their bags and wrappers in the bedroom and had just enough time for a cold drink before I had to leave to collect Adrian and Paula from school. They attended a local primary school about a five-minute drive away. They didn’t know yet that we were going to foster a baby and as I drove I pictured the looks on their faces when I told them. They would be so excited. Some of their friends had baby brothers and sisters and Paula, in particular, loved playing babies with her dolls: feeding them with a toy bottle, changing their nappies and sitting them on the potty. Sometimes Adrian joined in and more than once I’d been very moved by overhearing them tenderly nursing their ‘little darling’ and discussing their baby’s progress. Now we were going to do it for real, and I should make sure Adrian and Paula fully appreciated that a baby could not be treated as a toy and mustn’t be picked up unless I was in the room, which I’m sure they knew.

‘A baby!’ Paula squealed in delight as I met her in the playground and told her. ‘What, a real one?’

I smiled. ‘Yes, a real baby. I’m bringing him home from the hospital tomorrow.’

‘I can’t wait to tell my teacher!’ Paula exclaimed.

A minute later Adrian bounded over from his classroom exit, which was further along the building.

‘A baby!’ he exclaimed in surprise when I told him.

‘Yes, he was born today in the City Hospital,’ I said. ‘I’m going to collect him tomorrow afternoon.’

‘How was he born?’ Paula asked innocently as we began across the school playground.

‘Same as those rabbits you saw last year,’ Adrian said quickly, glancing over his shoulder to make sure his friends hadn’t heard Paula’s question.

‘Yuck!’ Paula said, screwing up her face. ‘That’s horrid.’

The previous summer we’d gone with friends to a working farm which had open days, and by chance in a fenced-off area of a barn we’d seen a rabbit giving birth. All the children watching had been enthralled and a little repulsed at this sight of nature in the raw, but as the man standing behind me had remarked: ‘At least we won’t have to explain the birds and bees to the kids now!’

‘What’s the baby’s name?’ Adrian now asked, changing the subject.

‘Harrison,’ I said.

‘Harrison,’ Paula repeated. ‘That’s a long name. I think I’ll call him Harry.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I agreed. ‘Baby Harry sounds good.’ And I briefly wondered why his mother had chosen the name Harrison, which was an unusual name in England and more popular in America.

When we arrived home Adrian and Paula ran upstairs to the spare bedroom to see all the baby things I’d told them I’d bought. ‘It’s like Christmas!’ Paula called, for rarely were there so many store bags and packages in the house.

After dinner the children didn’t want to play in the garden, as they had been doing recently in the nice weather, but wanted to help me prepare Harrison’s bedroom. I thought it was a good idea for them to be involved, so that they wouldn’t feel excluded when Harrison arrived and I was having to devote a lot of my time to him.

The three of us went upstairs and I gave Paula the job of starting to unwind the polythene from the new cot mattress, while Adrian helped me carry the sections of the cot into my bedroom. He also helped me assemble it and once the frame was bolted into place he and Paula carried in the new mattress. I lowered in the mattress and then fetched the new bedding from the spare room. Taking the blankets and sheets out of their wrappers, we made up the cot. I felt a pang of nostalgia as I remembered first Adrian and then Paula sleeping in the cot as tiny babies.

‘It’s not very big,’ Adrian remarked. ‘Did I fit in there?’

‘Yes. You were a lot, lot smaller then,’ I said, smiling. Adrian was going to be tall like his father, who unfortunately no longer lived with us.

‘Can I climb in?’ Adrian said, making a move to lift a leg over the lowered side.

‘No, you’ll break it,’ I said. ‘And don’t be tempted to try and get in when I’m not here, will you?’

Adrian shook his head.

‘What about me?’ Paula asked. ‘I’m smaller than Adrian. Can I get in?’

‘No. You’re too heavy too. It’s only made for a baby’s weight. And just a reminder: you both know you mustn’t ever pick up Harrison when I’m not in the room?’ Both children nodded. ‘I want you to help me, but we have to do it together, OK?’

‘OK,’ Adrian said quickly, clearly feeling this was obvious, while Paula said: ‘Ellen in my class has a baby sister and her mother told her babies don’t bounce. That seems a silly thing to say because of course babies don’t bounce. They’re not balls.’

‘It’s a saying,’ I said. ‘To try and explain that babies are fragile and need to be treated very gently.’

‘I’ll tell Ellen,’ Paula said. ‘She didn’t understand either.’

‘Well, she’s daft,’ Adrian said, unable to resist a dig at his sister.

‘No she’s not,’ Paula retaliated. ‘She’s my friend. You’re daft.’ Whereupon Adrian stuck out his tongue at Paula.

‘Enough,’ I said. ‘Are you helping me or not?’ I’d found since Paula had started school that the gap between their ages seemed to have narrowed and sometimes Adrian delighted in winding up his sister – just as many siblings do.

‘Helping,’ they chorused.

‘Good.’

With the cot made up and in place a little way from my bed we returned to the spare bedroom, where I left Adrian and Paula, now friends again, to finish unpacking the bags and packages while I took the three-in-one pram downstairs, a section at a time. It was a pram, pushchair and car seat all in one. I set up the pram in the hall and another wave of nostalgia washed over me as I remembered how proud I’d felt pushing Adrian and Paula in the pram to the local shops and park. The pram base unclipped to allow the pushchair, which was also the car seat, to be fitted, and I guessed I’d be using the car seat first when I collected Harrison from the hospital. I returned upstairs, where Adrian and Paula had finished unpacking all the items.

‘Well done,’ I said. ‘That’s a big help.’

They watched as I stood the baby bath to one side – I’d take it into the bathroom when needed – and then I set the changing mat on the bed and arranged disposable nappies, lotions, creams and nappy bags on the bedside cabinet. Now I was organized I was starting to feel more confident that I would remember what to do. As Jill had said: you simply feed one end and change the other – repeatedly, as I remembered.

Once we’d finished unpacking, the children played outside while I cleared up the discarded packaging and then, downstairs, distributed it between the various recycling boxes and the dustbin. I hadn’t heard from Jill since her phone call earlier and I wasn’t really expecting to until the following day, when she’d said she’d phone once she’d spoken to Cheryl, the social worker, with the arrangements for collecting Harrison and I hoped some more background information. Apart from knowing Harrison’s first name, that I was to collect him tomorrow afternoon and that his mother wasn’t drink or drug dependent, I knew nothing at all about Harrison. Although it wasn’t unusual for there to be a lack of information if a foster child arrived as an emergency, this placement wasn’t an emergency. Jill had said that the social services had known about the mother for months, so I really couldn’t understand why arrangements had been left until the last minute and no information was available. Usually when a placement is planned (as this one should have been) before the child arrives I receive essential information on the child, which includes relevant medical and social history; the background to the case; and the child’s routine – although, as Harrison was a newborn baby it would be largely up to me to establish his routine. I assumed Jill would bring the necessary forms with her when she visited the following day.

That night Paula was very excited at the prospect of Harrison’s arrival, and after I’d read her a bedtime story she told me all the things she was going to do for him: help feed him; change and wind him; play with him; push the pram when we took him to the park to feed the ducks and so on. Clearly Harrison was going to be very well looked after and also very busy; I knew I would be busy too – especially with contact. When a young baby is brought into foster care there is usually a high level of contact initially, when the parents see their baby with a supervisor present, usually for a couple of hours each day, six or even seven days a week. This is to allow the parents to bond with their baby and vice versa, and also so that a parenting assessment can be completed as part of the legal process that will be running in the background. But a high level of contact has its down side, for if the court decides not to return the baby to live with its parents and instead places the child for adoption, then clearly the bond that has been created between the parents and the baby has to be (painfully) broken. However, the alternative – if there is no contact – is that a baby could be returned to parents without an attachment, which can have a huge negative impact on their future together and particularly for the child. I was, therefore, anticipating taking Harrison to and from supervised contact at the family centre every day.

So that when Jill phoned the following morning and said there wouldn’t be any contact at all I was shocked and confused.