Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

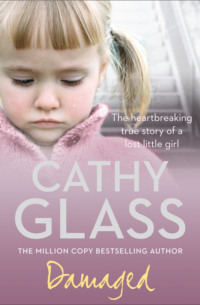

Kitabı oku: «Damaged: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Forgotten Child», sayfa 2

Chapter Two The Road to Jodie

I had started fostering twenty years before, before I had even had my own children. One day I was flicking through the paper when I saw one of those adverts – you might have seen them yourself. There was a black-and-white, fuzzy photograph of a child and a question along the lines of: Could you give little Bobby a home? For some reason it caught my eye, and once I’d seen it I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I don’t consider myself a sentimental person, but for some reason I couldn’t get the picture out of my mind. I talked about it with my husband; we knew we wanted a family of our own at some point, and I was looking forward to that, but in the meantime I knew that I could give a good home to child who needed it. I’d always felt a bond with children and had once had ambitions to teach.

‘We’ve got the room,’ I said, ‘and I know I would love working with children. Why don’t we at least find out a little bit more about it?’

So I picked up the phone, replied to the advertisement and before long we found ourselves on an induction course that introduced us to the world of foster care. Then, after we’d satisfied all the requirements and done the requisite training, we took in our first foster child, a troubled teenager in need of a stable home for a while. That was it. I was hooked.

Fostering, I discovered, is by no means easy. If a carer goes into it expecting to take in a little Orphan Annie, or an Anne of Green Gables, then he or she is in for a nasty shock. The sweet, mop-headed child who has had a little bad luck and only needs a bit of love and affection to thrive and blossom and spread happiness in the world doesn’t exist. Foster children don’t come into your home wide-eyed and smiling. They tend to be withdrawn because of what has happened to them and will often be distant, angry and hard to reach, which is hardly surprising. In worse cases, they can be verbally or even physically aggressive and violent. The only constant factor is that each one is different, and that they need attention and kindness to get through their unhappiness. It is never an easy ride.

The first year of fostering was by no means easy for me – and come to think of it, no year since has been what I would call ‘easy’ – but by the end of it I knew I wanted to continue. A foster carer will generally know almost at once if it is something they want to carry on doing or not, and certainly will by the end of that first year. I’d found something I had a talent for, and that was extremely rewarding and I wanted to carry on, even while I had my own children. I found that the difference I made to my foster children’s lives, even if it was a small one, stayed with me. It was not that I was the most selfless being since Mother Teresa, or that I was particularly saintly – I believe that we do these things for our own ends, and mine was the satisfaction I got from the whole process of making things better for children who needed help.

While my children were small I fostered teenagers, as it’s usually recommended that you take in children who are at a different stage to your own. As Adrian and Paula grew up, I began to take in younger ones, which meant that I never had to deal with the kind of serious drug problems that are endemic among a lot of teenagers these days – for which I am most grateful. My two grew up knowing nothing other than having foster children living with us, so it was something they accepted completely. Of course, when they were little, they were sometimes frustrated at having to share me with other children. Foster children, by definition, need a lot of time and attention and sometimes that felt never-ending to my two. After a day of pouring my energies into fostering, with its meetings and training, I would then have paperwork to see to, and that took its toll on the amount of time I had left over for my own family. But no matter how much they resented missing out on some of my time, they never took it out on the foster children who shared our home. Somehow, they seemed to understand that these children had come from difficult backgrounds, and that they had had a rough start. In their own way, my children were sympathetic and did their best to make life a bit easier for whichever troubled child was living with us. It’s something I’ve noticed in other children besides my own – there is often a lot more understanding and empathy there than we would expect.

Adrian and Paula have certainly had to put up with a lot over the years – particularly when my husband and I divorced – but they have never complained about all the troubled youngsters coming and going in their home. Over the years, we’ve experienced all types of children, most of whom have exhibited ‘challenging behaviour’. The majority of children who come to me have suffered from neglect of one sort or another, and funnily enough that is something I find relatively easy to understand. When parents have addictions to drink or drugs, or suffer from mental problems, they are obviously in no fit state to care for their children properly and look after their needs in a way they might be able to if they could overcome their problems. This kind of parenting is not purposefully cruel in the way that actual physical and sexual abuse is cruel – it is a sad side-effect of a different problem. The ideal outcome is that a child will be returned to its parents once the factors that caused the neglect, such as addiction, have been remedied.

A child who has suffered from neglect will have had a miserable time and can arrive in my house in a very troubled state. They can be full of brashness and bravado, which is usually a disguise for a complete lack of self-esteem. They can often be out-and-out naughty, as a result of having no boundaries or parental guidance at home, and as a way of seeking attention. Their anger and resentment can stem from the unpredictable nature of life at home, where nothing was ever certain – would Mum be too drunk to function today? Would Dad be spaced out or violent? – and where the borders between who was the adult and who was the child, and who was caring for whom, were often blurred. They may try to destroy things, or steal, or be manipulative and self-seeking. And, to be honest, when you know what some of them have had to put up with in their short lives, who can blame them?

The way that I’ve found is usually best with children from this kind of background is fairly simple: I provide stability and a positive environment in which good behaviour is rewarded with praise. Most children desire approval and want to be liked, and most are able to unlearn negative behaviour patterns and accept different ones when they realize how much better and easier life is with the new order. For many of them, a regular routine provides a blessed relief to the chaos and unpredictability of life at home, and they soon respond to a calm, positive environment where they know certain things will happen at certain times. Something as simple as knowing for sure when and where the next meal is coming from can provide an anchor for troubled children who’ve only ever known uncertainty and disappointment. Routine is safe; it is possible to get things right inside a routine – and getting things right is lovely when it means being praised, approved of and rewarded.

Of course, simple as it may sound, it is never easy and straightforward. And sometimes children come to me who’ve suffered much more severe levels of abuse, and who need much more professional help to get through their experiences. Many have learning difficulties and special needs. Some are removed from home too late, when they’re teenagers and have suffered so much that they are never able to get over what has happened; they’re not able to respond to a positive environment in the way a younger child might, and their futures look a lot bleaker.

Nevertheless, almost all my fostering experiences have been good ones, and the child has left our home in a better place than when they arrived.

As I drove home from the meeting at Social Services that day having agreed to take on Jodie, I knew that this child might be more of a handful than most, and wondered how best to tell the children about our new addition. They wouldn’t be best pleased. We’d had children before with ‘challenging behaviour’, so they knew what was in store. I thought of Lucy, who’d been with us for nearly two years, and was very well settled. I hoped Jodie’s disturbed outbursts wouldn’t set her back. Adrian, at seventeen, kept pretty much to himself, unless there was a crisis, or he couldn’t find his shirt in the morning. It was Paula I was most worried about. She was a sensitive, nervous child, and even though Jodie was five years younger than her, there was a risk she could be intimidated. Emotionally damaged children can wreak havoc in a family, even a well-integrated one. My children had always reacted well to the other children who had joined our family, even though we’d had a few rocky times, and I had no reason to think that this time would be any different.

I suspected the children wouldn’t be surprised by my news. It had been a few weeks since our last foster child had left, so it was time for a new challenge. I usually took a break of a couple of weeks between placements, to refresh myself mentally and physically, and give everyone time to regroup. I also needed to recover from the sadness of saying goodbye to someone I’d become close to; even when a child leaves on a high note, having made excellent progress and perhaps returning home to parents who are now able to provide a loving and caring environment, there is still a period when I mourn their going. It’s a mini-bereavement and something I have never got used to even though, a week or two later, I’d be revved up and ready to go again.

I decided to raise the subject of Jodie over dinner, which was where most of our discussions took place. Although I consider myself liberal, I do insist that the family eat together in the evenings and at weekends, as it’s the only part of the day when we’re all together.

For dinner that night I served shepherd’s pie, which was the children’s favourite. As they tucked in, I adjusted my voice to a light and relaxed tone.

‘You remember I mentioned I was going to a pre-placement meeting today?’ I said, aware they probably wouldn’t remember, because no one had been listening when I’d said it. ‘They told me all about a little girl who needs a home. Well, I’ve agreed to take her. She’s called Jodie and she’s eight.’

I glanced round the table for a reaction, but there was barely a flicker. They were busy eating. Even so, I knew they were listening.

‘I’m afraid she’s had a rough start and a lot of moves, so she’s very unsettled. She’s had a terrible home life and she’s already had some foster carers. Now they’re thinking of sending her to a residential unit if they can’t find someone to take her in, and you can imagine how horrible that would be for her. You know – a children’s home,’ I added, labouring the point.

Lucy and Paula looked up, and I smiled bravely.

‘Like me,’ said Lucy innocently. She had moved around a lot before she finally settled down with us, so she knew all about the disruption of moving.

‘No. Your moves were because of your relatives not being able to look after you. It had nothing to do with your behaviour.’ I paused, wondering if the discreet message had been picked up. It had.

‘What’s she done?’ Adrian growled, in his newly developed masculine voice.

‘Well, she has tantrums, and breaks things when she’s upset. But she’s still young, and I’m sure if we all pull together we’ll be able to turn her around.’

‘Is she seeing her mum?’ asked Paula, her eyes wide, imagining what for her would be the worst-case scenario: a child not seeing her mother.

‘Yes, and her dad. It will be supervised contact twice a week at the Social Services.’

‘When is she coming?’ asked Lucy.

‘Tomorrow morning.’

They all glanced at me and then at each other. Tomorrow there would be a new member of the family and, from the sounds of it, not an easy one either. I knew it must be unsettling.

‘Don’t worry,’ I reassured them. ‘I’m sure she’ll be fine.’ I realized I’d better be quick, as once dinner was over they’d vanish to their rooms, so I cut straight to the chase and reminded them of the ‘safer caring’ rules that were always in place when a new foster child arrived. ‘Now, remember, there are a lot of unknowns here, so you need to be careful for your own protection. If she wants you to play, it’s down here, not upstairs, and Adrian, don’t go into her room, even if she asks you to open a window. If there’s anything like that, call me or one of the girls. And remember, no physical-contact games like piggy back until we know more. And, obviously, don’t let her in your room, OK?’

‘Yes, Mum,’ he groaned, looking even more uncomfortably adolescent. He’d heard it all before, of course. There are standard codes of practice that apply in the homes of all foster carers, and my lot were well aware of how to behave. But Adrian could sometimes be too trusting for his own good.

‘And obviously, all of you,’ I said, addressing the three of them, ‘let me know if she confides anything about her past that gives you cause for concern. She’ll probably forge a relationship with you before she does with me.’

They all nodded. I decided that that was enough. They’d got the general picture, and they were pretty clued up. The children of foster carers tend to grow up quickly, as a result of the issues and challenges they’re exposed to. But not as quickly as the fostered children themselves, whose childhoods have often been sacrificed on the pyre of daily survival.

After dinner, as expected, the children disappeared to their rooms and the peace of another quiet evening descended on the house. It had gone off as well as I could have expected and I felt pleased with their maturity and acceptance of the situation.

‘So far so good,’ I thought, as I loaded the dishwasher. Then I settled down myself to watch the television with no idea when I’d next have the opportunity.

Chapter Three The Arrival

It was a wet and cold spring day in April. Rain hammered on the windows as I prepared for Jodie’s arrival. She was due at midday, but I was sure she’d be early. I stood in what was to be her new bedroom, and tried to see it through the eyes of a child. Was it appealing and welcoming? I had pinned brightly coloured posters of animals to the walls, and bought a new duvet cover with a large print of a teddy bear on it. I’d also propped a few soft toys on the bed, although I was sure that Jodie, having been in care for a while, was likely to have already accumulated some possessions. The room looked bright and cheerful, the kind of place that an eight-year-old girl would like as her bedroom. All it needed now was its new resident.

I took a final look around, then came out and closed the door, satisfied I’d done my best. Continuing along the landing, I closed all the bedroom doors. When it came to showing her around, it would be important to make sure she understood privacy, and this would be easier if the ground rules had been established right from the start.

Downstairs, I filled the kettle and busied myself in the kitchen. It was going to be a hectic day, and even after all these years of fostering I was still nervous. The arrival of a new child is a big event for a foster family, perhaps as much as for the child herself. I hoped Jill would arrive early, so that the two of us could have a quiet chat and offer moral support before the big arrival.

Just before 11.30, the doorbell rang. I opened the door to find Gary, soaking wet from his walk from the station. I ushered him in, offered him a towel and coffee, and left him mopping his brow in the lounge while I returned to the kitchen. Before the kettle had a chance to boil, the bell rang again. I went to the door, hoping to see Jill on the doorstep. No such luck. It was the link worker from yesterday, Deirdre, along with another woman, who was smiling bravely.

‘This is Ann, my colleague,’ said Deirdre, dispensing with small talk. ‘And this is Jodie.’

I looked down, but Jodie was hiding behind Ann, and all I could see was a pair of stout legs in bright red trousers.

‘Hi, Jodie,’ I said brightly. ‘I’m Cathy. It’s very nice to meet you. Come on in.’

She must have been clinging to Ann’s coat, and decided she wasn’t going anywhere, as Ann was suddenly pulled backwards, nearly losing her balance.

‘Don’t be silly,’ snapped Deirdre, and made a grab behind her colleague. Jodie was quicker and, I suspected, stronger, for Ann took another lurch, this time sideways. Thankfully, our old cat decided to put in a well-timed appearance, sauntering lazily down the hall. I took my cue.

‘Look who’s come to see you, Jodie!’ I cried, the excitement in my voice out of all proportion to our fat and lethargic moggy. ‘It’s Toscha. She’s come to say hello!’

It worked – she couldn’t resist a peep. A pair of grey-blue eyes, set in a broad forehead, peered out from around Ann’s waist. Jodie had straw-blonde hair, set in pigtails, and it was obvious from her outfit alone that her previous carers had lost control. Under her coat she was wearing a luminous green T-shirt, red dungarees and wellies. No sensible adult would have dressed her like this. Clearly, Jodie was used to having her own way.

With her interest piqued, she decided take a closer look at the cat, and gave Ann another shove, sending them both stumbling over the doorstep and into the hall. Deirdre followed, and the cat sensibly nipped out. I quickly closed the door.

‘It’s gone!’ Jodie yelled, her face pinched with anger.

‘Don’t worry, she’ll be back soon. Let’s get you out of your wet coat.’ And before the loss of the cat could escalate into a scene, I undid her zip, and tried to divert her attention. ‘Gary’s in the lounge waiting for you.’

She stared at me for a moment, looking as though she’d really like to hit me, but the mention of Gary, a familiar name in an unfamiliar setting, drew her in. She wrenched her arms free of the coat, and stomped heavily down the hall before disappearing into the lounge. ‘I want that cat,’ she growled at Gary.

The two women exchanged a look which translated as, ‘Heaven help this woman. How soon can we leave?’

I offered them coffee and showed them through to the lounge. Jodie had found the box of Lego and was now sitting cross-legged in the middle of the floor, making a clumsy effort to force two pieces together.

Returning to the kitchen, I took down four mugs, and started to spoon in some instant coffee. I heard heavy footsteps, then Jodie appeared in the doorway. She was an odd-looking child, not immediately endearing, but I thought this was largely because of the aggressive way she held her face and body, as though continually on guard.

‘What’s in ’ere?’ she demanded, pulling open a kitchen drawer.

‘Cutlery,’ I said needlessly, as the resulting clatter had announced itself.

‘What?’ she demanded, glaring at me.

‘Cutlery. You know: knives, forks and spoons. We’ll eat with those later when we have dinner. You’ll have to tell me what you like.’

Leaving that drawer, she moved on to the next, and the next, intent on opening them all. I let her look around. I wasn’t concerned about her inquisitiveness, that was natural; what worried me more was the anger in all her movements. I’d never seen it so pronounced before.

With all the drawers opened, and the kettle boiled, I took out a plate and a packet of biscuits.

‘I want one,’ she demanded, lunging for the packet.

I gently stopped her. ‘In a moment. First I’d like you to help me close these drawers, otherwise we’ll bump into them, won’t we?’

She looked at me with a challenging and defiant stare. Had no one ever stopped her from doing anything, or was she deliberately testing me? There was a few seconds’ pause, a stand-off, while she considered my request. I noticed how overweight she was. It was clear she’d either been comfort eating, or had been given food to keep her quiet; probably both.

‘Come on,’ I said encouragingly, and started to close the drawers. She watched, then with both hands slammed the nearest drawer with all her strength.

‘Gently, like this.’ I demonstrated, but she didn’t offer any more assistance, and I didn’t force the issue. She’d only just arrived, and she had at least compromised by closing one.

‘Now the biscuits,’ I said, arranging them on the plate. ‘I’d like your help. I’m sure you’re good at helping, aren’t you?’

Again she fixed me with her challenging, almost derisory stare, but there was a hint of intrigue, a spark of interest in the small responsibility I was about to bestow on her.

‘Jodie, I’d like you to carry this into the lounge and offer everyone a biscuit, then take one for yourself, all right?’

I placed the plate squarely in her chubby, outstretched hands, and wondered what the chances were of it arriving intact. The digestives pitched to the left as she turned, and she transferred the plate to her left hand, clamping the right on top of the biscuits, which was at least safe, if not hygienic.

I followed with the tray of drinks, pleased that she’d done as I’d asked. I handed out the mugs of coffee as the doorbell rang, signalling our last arrival. Jodie jumped up and made a dash for the door. I quickly followed; it’s not good practice for a child to be answering the door, even if guests are expected. I explained this to Jodie, then we opened it together.

Jill stood on the doorstep. She was smiling encouragingly, and looked down at the sullen-faced child staring defiantly up at her.

‘Hi,’ said Jill brightly. ‘You must be Jodie.’

‘I wanted to do it,’ protested Jodie, before stomping back down the hall to rejoin the others.

‘Is everything all right?’ Jill asked as she came in.

‘OK so far. No major disasters yet, anyway.’ I took Jill’s coat, and she went through to the lounge. I fetched another coffee, and the paperwork began. There’s a lot of form filling when a child is placed with new carers, and a lot of coffee. Gary was writing furiously.

‘I’ve only just completed the last move,’ he said cheerfully. ’Not to mention the three-day one before that. Is it Cathy with a C?’

I confirmed that it was, then gave him my postcode and my doctor’s name and address. Jodie, who’d been reasonably content watching him, and had obviously been party to the process many times before, decided it was time to explore again. She hauled herself up, and disappeared into the kitchen. I couldn’t allow her to be in there alone; quite apart from the risk of her raiding the cupboards, there were any number of implements which could have been harmful in the wrong hands. I called her, but she didn’t respond. I walked in and found her trying to yank open the cupboard under the sink, which was protected by a child lock, as it contained the various cleaning products.

‘Come on, Jodie, leave that for now. Let’s go into the lounge,’ I said. ‘I’ll show you around later. We’ll have plenty of time once they’ve gone.’

‘I want a drink,’ she demanded, pulling harder on the cupboard door.

‘OK, but it’s not in there.’

I opened the correct cupboard, where I kept a range of squashes. She peered in at the row of brightly coloured bottles.

‘Orange, lemon, blackcurrant or apple?’ I offered.

‘Coke,’ she demanded.

‘I’m sorry, we don’t have Coke. It’s very bad for your teeth.’ Not to mention hyperactivity, I thought to myself. ‘How about apple? Paula, my youngest daughter, likes apple. You’ll meet her later.’

‘That one.’ She tried to clamber on to the work surface to retrieve the bottle.

I took down the bottle of blackcurrant and poured the drink, then carried it through and placed it on the coffee table. I drew up the child-sized wicker chair, which is usually a favourite.

‘This is just the right size for you,’ I said. ‘Your very own seat.’

Jodie ignored me, grabbed her glass, and plonked herself in the place I had vacated on the sofa next to Jill. I sat next to Gary, while Jill pacified Jodie with a game on her mobile phone. I watched her for a few moments. So this was the child who was going to be living with us. It was hard to make much of her so early on; most children displayed difficult behaviour in their first few days in a new home. Nevertheless, there was an unusual air about her that I couldn’t quite understand: it was anger, of course, and stubbornness, mixed with something else that I wasn’t sure I had seen before. Only time would tell, I thought. I observed Jodie’s uncoordinated movements and the way her tongue lolled over her bottom lip. I noted almost guiltily how it gave her a dull, vacant air, and reminded myself that she was classified as having only ‘mild’ learning difficulties, rather than ‘severe’.

A quarter of an hour later, all the placement forms had been completed. I signed them and Gary gave me my copies. Deirdre and Ann immediately stood to leave.

‘We’ll unpack the car,’ said Ann. ‘There’s rather a lot.’

Leaving Jodie with Gary and Jill, I quickly put on my shoes and coat, and we got gradually drenched as we went back and forth to the car. ‘Rather a lot’ turned out to be an understatement. I’d never seen so many bags and holdalls for a child in care. We stacked them the length of the hall, then the two women said a quick goodbye to Jodie. She ignored them, obviously feeling the rejection. Gary stayed for another ten minutes, chatting with Jodie about me and my home, then he too made a move to leave.

‘I want to come,’ she grinned, sidling up to him. ‘Take me with you. I want to go in your car.’

‘I don’t have a car,’ said Gary gently. ‘And you’re staying with Cathy. Remember we talked about it? This is your lovely new home now.’ He picked up his briefcase and got halfway to the door, then Jodie opened her mouth wide and screamed. It was truly ear piercing. I rushed over and put my arms around her, and nodded to Gary to go. He slipped out, and I held her until the noise subsided. There were no tears, but her previously pale cheeks were now flushed bright red.

The last person left was Jill. She came out into the hall and got her coat.

‘Will you be all right, Cathy?’ she asked, as she prepared to venture out into the rain. ‘I’ll phone about five.’ She knew that the sooner Jodie and I were left alone, the sooner she’d settle.

‘We’ll be fine, won’t we, Jodie?’ I said. ‘I’ll show you around and then we’ll unpack.’

I was half expecting another scream, but she just stared at me, blank and uncomprehending. My heart went out to her; she must have felt so lost in what was her sixth home in four months. I held her hand as we saw Jill out.

Now it was just the two of us. I’d been in this situation many times before, welcoming a confused and hurt little person into my home, waiting patiently as they acclimatized to a new and strange environment, but this felt different somehow. There was something in the blankness in Jodie’s eyes that was chilling. I hadn’t seen it before, in a child or an adult. I shook myself mentally. Come on, I cajoled. She’s a little girl and you’ve got twenty years’ experience of looking after children. How hard can it be?

I led her back into the living room and, right on cue, Toscha reappeared. I showed Jodie the correct way to stroke her, but she lost interest as soon as I’d begun.

‘I’m hungry. I want a biscuit.’ She made a dash for the kitchen.

I followed and was about to explain that too many biscuits aren’t good, when I noticed a pungent smell. ‘Jodie, do you want the toilet?’ I asked casually.

She shook her head.

‘Do you want to do a poo?’

‘No!’ She grinned, and before I realized what she was doing, her hand was in her pants, and she smeared faeces across her face.

‘Jodie!’ I grabbed her wrist, horrified.

She cowered instantly, protecting her face. ‘You going to hit me?’

‘No, Jodie. Of course not. I’d never do that. You’re going to have a bath, and next time tell me when you want the toilet. You’re a big girl now.’

Slowly, I led my new charge up the stairs and she followed, clumsy, lumbering and her face smeared with excrement.

What had I let myself in for?

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.