Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

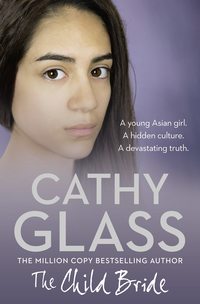

Kitabı oku: «The Child Bride»

Copyright

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the children.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2014

A catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photography by Nicky Rojas (posed by model)

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780007590001

Ebook Edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007590018

Version: 2016-04-22

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Also by Cathy Glass

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Chapter One: Petrified

Chapter Two: Different House

Chapter Three: Good Influence

Chapter Four: Sobbing

Chapter Five: Scared into Silence

Chapter Six: Dreadful Feeling

Chapter Seven: Desperate

Chapter Eight: Lost Innocence

Chapter Nine: Ordeal

Chapter Ten: Optimistic

Chapter Eleven: Worries and Worrying

Chapter Twelve: Only Fourteen

Chapter Thirteen: Consequences

Chapter Fourteen: Review

Chapter Fifteen: Vicious Threats

Chapter Sixteen: Zeena’s Story

Chapter Seventeen: A Special Holiday

Chapter Eighteen: Overwhelmed

Chapter Nineteen: Atrocity

Chapter Twenty: I Miss Hugs

Chapter Twenty-One: Police Business

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Suitcase

Chapter Twenty-Three: Other Victims

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Silence Was Deafening

Chapter Twenty-Five: Heartbreaking

Chapter Twenty-Six: Turn of Events

Chapter Twenty-Seven: More than I Deserve

Epilogue: Deserves the Best

Contacts

Exclusive sample chapter

Cathy Glass

If you loved this book …

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

A note from The Fostering Network

About the Publisher

Also by Cathy Glass

Damaged

Hidden

Cut

The Saddest Girl in the World

Happy Kids

The Girl in the Mirror

I Miss Mummy

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell

My Dad’s a Policeman (a Quick Reads novel)

Run, Mummy, Run

The Night the Angels Came

Happy Adults

A Baby’s Cry

Happy Mealtimes for Kids

Another Forgotten Child

Please Don’t Take My Baby

Will You Love Me?

About Writing and How to Publish

Daddy’s Little Princess

Acknowledgements

A big thank-you to my editor, Holly; my literary agent, Andrew; Carole, Vicky, Laura, Hannah, Virginia and all the team at HarperCollins.

Prologue

A small child walks along a dusty path. She has been on an errand for her aunt and is now returning to her village in rural Bangladesh. The sun is burning high in the sky and she is hot and thirsty. Only another 300 steps, she tells herself, and she will be home.

The dry air shimmers in the scorching heat and she keeps her eyes down, away from its glare. Suddenly she hears her name being called close by and looks over. One of her teenage cousins is playing hide and seek behind the bushes.

‘Go away. I’m hot and tired,’ she returns, with childish irritability. ‘I don’t want to play with you now.’

‘I have water,’ he says. ‘Wouldn’t you like a drink?’

She has no hesitation in going over. She is very thirsty. Behind the bush, but still visible from the path if anyone looked, he forces her to the ground and rapes her.

She is nine years old.

Chapter One

Petrified

‘And she wouldn’t feel more comfortable with an Asian foster carer?’ I queried.

‘No, Zeena has specifically asked for a white carer,’ Tara, the social worker, continued. ‘I know it’s unusual, but she is adamant. She’s also asked for a white social worker.’

‘Why?’

‘She says she’ll feel safer, but won’t say why. I want to accommodate her wishes if I can.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said, puzzled. ‘How old is she?’

‘Fourteen. Although she looks much younger. She’s a sweet child, but very traumatized. She’s admitted she’s been abused, but is too frightened to give any details.’

‘The poor kid,’ I said.

‘I know. The child protection police office will see her as soon as we’ve moved her. She’s obviously suffered, but for how long and who abused her, she’s not saying. I’ve no background information. Sorry. All we know is that Zeena has younger siblings and her family is originally from Bangladesh, but that’s it I’m afraid. I’ll visit the family as soon as I’ve got Zeena settled. I want to collect her from school this afternoon and bring her straight to you. The school is working with us. In fact, they were the ones who raised the alarm and contacted the social services. I should be with you in about two hours.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll be here.’

‘I’ll phone you when we’re on our way,’ Tara clarified. ‘I hope Zeena will come with me this time. She asked to go into care on Monday but then changed her mind. Her teacher said she was petrified.’

‘Of what?’

‘Or of whom? Zeena wouldn’t say. Anyway, thanks for agreeing to take her,’ Tara said, clearly anxious to be on her way and to get things moving. ‘I’ll phone as soon as I’ve collected her from school.’

We said a quick goodbye and I replaced the handset. It was only then I realized I’d forgotten to ask if Zeena had any special dietary requirements or other special considerations, but my guess was that as Tara had so little information on Zeena, she wouldn’t have known. I’d find out more when they arrived. With an emergency placement – as this one was – the background information on the child or children is often scarce to begin with, and I have little notice of the child’s arrival; sometimes just a phone call in the middle of the night from the duty social worker to say the police are on their way with a child. If a move into care is planned, I usually have more time and information.

I’d been fostering for twenty years and had recently left Homefinders, the independent fostering agency (IFA) I’d been working with, because they’d closed their local branch and Jill, my trusted support social worker, had taken early retirement. I was now fostering for the local authority (LA). While it made no difference to the child which agency I fostered for, I was having to get used to slightly different procedures, and doing without the excellent support of Jill. I did have a supervising social worker (as the LA called them), but I didn’t see her very often, and I knew that, unlike Jill, she wouldn’t be with me when a new child arrived. It wasn’t the LA’s practice.

It was now twelve noon, so if all went to plan Tara and Zeena would be with me at about two o’clock. The secondary school Zeena attended was on the other side of town, about half an hour’s drive away. I went upstairs to check on what would be Zeena’s bedroom for however long she was with me. I always kept the room clean and tidy and with the bed made up, as I never knew when a child would arrive. The room was never empty for long, and Aimee, whose story I told in Another Forgotten Child, had left us two weeks previously. The duvet cover, pillow case and cushions were neutral beige, which would be fine for a fourteen-year-old girl. To help her settle and feel more at home I would encourage her to personalize her room by adding posters to the walls and filling the shelves with her favourite books, DVDs and other knick-knacks that litter teenagers’ bedrooms.

Satisfied that the room was ready for Zeena, I returned downstairs. I was nervous. Even after many years of fostering, awaiting the arrival of a new child or children is an anxious time. Will they be able to relate to me and my family? Will they like us? Will I be able to meet their needs, and how upset or angry will they be? Once the child or children arrive I’m so busy there isn’t time to worry. Sometimes teenagers can be more challenging than younger children, but not always.

At 1.30 the landline rang. It was Tara now calling from her mobile.

‘Zeena is in the car with me,’ she said quickly. ‘We’re outside her school but she wants to stop off at home first to collect some of her clothes. We should be with you by three o’clock.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘How is she?’

There was a pause. ‘I’ll tell you when I see you,’ Tara said pointedly.

I replaced the receiver and my unease grew. From Tara’s response I guessed something was wrong. Perhaps Zeena was very upset. Otherwise Tara would have been able to reassure me that Zeena was all right instead of saying, ‘I’ll tell you when I see you.’

My three children were young adults now. Adrian, twenty-two, had returned from university and was working temporarily in a supermarket until he decided what he wanted to do – he was thinking of accountancy. Lucy, my adopted daughter, was nineteen, and was working in a local nursery school. Paula, just eighteen, was in the sixth form at school and had recently taken her A-level examinations. She was hoping to attend university in September. I was divorced; my husband, John, had run off with a younger woman many years previously, and while it had been very hurtful for us all at the time, it was history now. The children (as I still referred to them) wouldn’t be home until later, and I busied myself in the kitchen.

At 2.15 the telephone rang again. ‘We’re leaving Zeena’s home now,’ Tara said tightly. ‘Her mother had her suitcase packed ready. We’ll be with you in about half an hour.’

I thanked her for letting me know and replaced the receiver. I sensed there was trouble in what Tara had left unsaid, and I was surprised Zeena’s mother had packed her daughter’s case so quickly. She couldn’t have known for long that her daughter was going into care – Tara hadn’t known herself for definite until half an hour ago – yet she had spent that time packing. Usually parents are so angry when their child first goes into care (unless they’ve requested help) that they have to be persuaded to part with some of their child’s clothes and personal possessions to help them settle in at their carer’s. I’d have been less surprised if Tara had said there’d been a big scene at Zeena’s home and she wouldn’t be coming into care after all, for teenagers are seldom forced into care against their wishes, even if it is for their own good.

Now assured that Zeena was definitely on her way, I texted Adrian, Paula and Lucy: Zeena, 14, arriving soon. C u later. Love Mum xx.

I was looking out of the front-room window when, about half an hour later, a car drew up. I could see the outlines of two women sitting in the front, and then, as the doors opened and they got out, I went into the hall and to the front door to welcome them. The social worker was carrying a battered suitcase.

‘Hi, I’m Cathy,’ I said, smiling.

‘I’m Tara, Zeena’s social worker,’ she said. ‘Pleased to meet you. This is Zeena.’

I smiled at Zeena. ‘Come on in, love,’ I said cheerily.

Had I not known she was fourteen I’d have said she was much younger – nearer eleven or twelve. She was petite, with delicate features, olive skin and huge dark eyes. But what immediately struck me was how scared she looked. She held her body tense and kept glancing anxiously towards the road outside until I closed the front door. Then she put her hand on the door to test it was shut.

Tara saw this and asked me, ‘You do keep the door locked? It can’t be opened from the outside?’

‘Not without a key,’ I said.

‘Good. And there’s a security spy-hole,’ Tara said, pointing it out to Zeena. ‘So you or Cathy can check before you open the door.’

Zeena gave a small polite nod but didn’t look reassured. Clearly security was going to be an issue, and I felt slightly unsettled. Zeena slipped off her shoes and then lowered her headscarf, which had been draped loosely over her head. She had lovely long, black, shiny hair, similar to my daughter Lucy’s. It was tied back in a ponytail, which made her look even younger. She was wearing her school uniform, with leggings under her pleated skirt.

‘Leave the case in the hall for now,’ I said to Tara. ‘I’ll take it up to Zeena’s room later. Let’s go and sit down.’

Tara set the case by the coat stand and I led the way into the living room, which was at the rear of the house and looked out over the garden. When I fostered young children I always had toys ready to help take their minds off being separated from their parents, and on fine days the patio doors would be open. But not today – the air was chilly, although we were now in the month of May.

Tara sat on the sofa and Zeena sat next to her.

‘Would you like a drink?’ I asked them both.

‘Could I have a glass of water, please?’ Tara said. Then, turning to Zeena, she added, ‘Would you like one too?’

‘Yes, please,’ Zeena said quietly.

‘Or I have juice?’ I suggested.

‘Water is fine, thank you,’ Zeena said very politely.

I went into the kitchen, poured two glasses of water and, returning, placed them on the coffee table within their reach. I sat in one of the easy chairs. Tara drank some of her water, but Zeena left hers untouched. I could see how tense and anxious she was. It was as though she was on continual alert, ready to flee at a moment’s notice. I’d seen this before in children I’d fostered who’d been badly abused. They were always on their guard, listening out for any unusual sound and continually scanning their surroundings for signs of danger.

‘Thank you for looking after Zeena,’ Tara began, setting her glass on the coffee table. ‘This has all been such a rush I haven’t had a chance to look at your details properly and tell Zeena. You’ve got three adult children, I believe?’

‘Yes, one boy and two girls,’ I said, smiling at Zeena and trying to put her at ease. ‘You’ll meet them later.’

‘And you don’t have any other males in the house, apart from your son?’ Tara asked.

‘No. I’m divorced.’

She glanced at Zeena, who seemed to draw some comfort from this and gave a small nod. Tara had a nice manner about her, gentle and considerate. I guessed she was in her mid-thirties; she had short, wavy brown hair and was dressed in a long jumper over jeans.

‘Zeena is very anxious about her safety,’ Tara said to me. ‘She has a mobile phone, and I’ve put my telephone number in it, also the social services’ emergency out-of-hours number, and the police. It’s a pay-as-you-go phone. She has credit on it now. Can you make sure she keeps the phone in credit, please? It’s important for her safety.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said, and felt my anxiety heighten.

‘Zeena knows she can phone the police at any time if she’s worried about her safety,’ Tara said. ‘Her family won’t be given this address. No one knows where she is staying, and the school know they mustn’t give out this address. We weren’t followed here, but please be cautious and check before answering the door.’

‘I always check at night,’ I said, uneasily. ‘But what am I checking for?’

Tara looked at Zeena.

‘My family,’ Zeena said very quietly, her hands trembling in her lap.

‘Please try not to worry,’ I said, feeling I should reassure her. ‘You’ll be safe here with me.’

Zeena’s eyes rounded in fear as she finally met my gaze, and I could see she dearly wished she could believe me. ‘I hope so,’ she said almost under her breath. ‘Because if they find me, they’ll kill me.’

Chapter Two

Different House

I looked at Tara. My mouth had gone dry and my heart was drumming loudly. I could see that Zeena’s comment had shaken Tara as much as it had me. Zeena had her head slightly lowered and was staring at the floor, wringing the headscarf she held in her lap. Suddenly the silence was broken by the sound of the front door opening. Zeena shot up from the sofa.

‘Who’s that?’ she cried.

‘It’s all right,’ I said, also standing. ‘That’ll be my daughter, Paula, back from sixth form.’

Zeena didn’t immediately relax and return to the sofa but remained standing, anxiously watching the living-room door.

‘We’re in here, love,’ I called to Paula, who was taking off her shoes and jacket in the hall.

Paula came into the living room, and I saw Zeena relax. ‘This is Zeena and her social worker, Tara,’ I said, introducing them.

‘Hi,’ Paula said, glancing at them both.

‘I’m pleased to meet you,’ Zeena said quietly. ‘Thank you for letting me stay in your home.’

I could see Paula was as touched as I was by Zeena’s politeness.

‘Do you think Paula could wait here with Zeena while we go and have a chat?’ Tara now asked me.

‘Sure,’ Paula said easily.

‘Thanks, love,’ I said. ‘We’ll be in the front room if we’re needed.’

Tara stood and Zeena returned to the sofa. Paula sat next to her. Both girls looked a little uncomfortable and self-conscious, but then teenagers often do when meeting someone new.

In the front room Tara closed the door so we couldn’t be overheard, and we sat opposite each other. Now she no longer needed to put on a brave and professional face for Zeena’s sake, she looked very worried indeed.

‘I don’t know what’s been going on at home,’ she began, with a small sigh. ‘But I’m very concerned. Zeena’s father and another man went to her school today. They were shouting and demanding to see Zeena. They only left when the headmistress threatened to call the police. Zeena was so scared she hid in a cupboard in the stockroom. It took a lot of persuading to get her to come out after they’d gone.’

‘What did they want?’ I asked, equally concerned.

‘I don’t know,’ Tara said. ‘But they’d come for Zeena. There was no sign of them when I arrived at the school, but Zeena begged me to take her out the back entrance in case they were still waiting at the front. As soon as we were in my car she insisted I put all the locks down and drive away fast. She phoned her mother from the car. It was a very heated discussion with raised voices, although I don’t know what was said as Zeena spoke in Bengali. She was distressed after the call but wouldn’t tell me what her mother had said. I’m going to have to take an interpreter with me when I visit Zeena’s parents.’

‘And Zeena won’t tell you why she’s so scared?’ I asked. ‘Or why she thinks her family want to kill her?’

‘No. I’m hoping the child protection police officer will have more success. She’s very good.’

‘The poor child,’ I said again. ‘She looks petrified. It’s making me nervous too.’

‘I know. I’m sorry to have to put you and your family through this. It seems to be escalating. But don’t hesitate to call the police if you need to.’ Which only heightened my unease.

‘Perhaps her parents will calm down once they accept Zeena is in care,’ I suggested, which often happened when a child was fostered.

‘Hopefully,’ Tara said. ‘Zeena told me in the car that she needed to see a doctor.’

‘Why? Is she hurt?’ I asked, concerned.

‘No. I asked her if it was an emergency – I would have taken her straight to the hospital, but she said she could wait for an appointment. Can you arrange for her to see a doctor as soon as possible, please?’

‘Yes, of course. Will she want to see her own doctor, or shall I register her with mine?’

‘We’ll ask her. When we stopped off to get her clothes her mother had the suitcase ready in the hall. She wouldn’t let Zeena into the house and was angry, although again I couldn’t understand what she was saying to Zeena. Eventually she dumped the case on the pavement and slammed the door in our faces. Zeena pressed the bell a few times, but her mother wouldn’t open the door again. When we got in the car Zeena told me she had asked her mother if she could say goodbye to her younger brothers and sisters, but her mother had refused and called her a slut and a whore.’

I flinched. ‘What a dreadful thing for a mother to say to her daughter.’

‘I know,’ Tara said, her brow furrowing. ‘And it raises concerns about the other children at home. I shall be checking on them.’

‘Will Zeena be going to school tomorrow?’ I thought to ask.

‘We’ll see how she feels and ask her in a moment.’ Tara glanced at her watch. ‘I think I’ve told you everything I know. Let’s go into the living room and talk to Zeena. Then I need to get back to the office and make some phone calls. At least Zeena has some clothes with her.’

‘Yes. That will help,’ I said. Often the children I looked after arrived in what they stood up in, which meant they had to make do from my supply of spares until I had the chance to go to the shops and buy them new clothes.

Paula and Zeena were sitting on the sofa, still looking self-conscious, but at least talking a little.

‘Thanks, love,’ I said to Paula, who now stood.

‘Is it OK if I go to my room?’ she asked. ‘Or do you still need me?’

‘No, do as you like,’ I said. ‘Thanks for your help.’

‘Thank you for sitting with me,’ Zeena said politely.

‘You’re welcome,’ Paula said, smiling at Zeena. ‘Catch up with you later.’ She left the room.

Tara returned to sit on the sofa and I took the easy chair.

‘I’ve explained to Cathy what happened at school this morning,’ Tara said to Zeena. ‘Also that you need to see a doctor.’

Zeena gave a small nod and looked down.

‘Would you like to see your own family doctor?’ Tara now asked her.

‘No!’ Zeena said, sitting bolt upright and staring at Tara. ‘No. You mustn’t take me there. Please don’t make me see him. I won’t go.’

‘All right,’ Tara said, placing a reassuring hand on her arm. ‘I won’t force you to see him, of course not. You can see Cathy’s doctor. I just wanted to hear your views. You may have preferred to see the doctor you knew.’

‘No!’ Zeena cried again, shaking her head.

‘I’ll arrange for you to see my doctor then,’ I said quickly, for clearly this was causing Zeena a lot of distress. ‘There are two doctors in the practice I use, a man and a woman. They are both lovely people and good doctors.’

Zeena looked at me. ‘Are they white?’ she asked.

‘Yes. But I can arrange for you to see an Asian doctor if you prefer. There is another practice not far from here.’

‘No!’ Zeena cried again. ‘I can’t see an Asian doctor.’

‘All right, love,’ I said. ‘Don’t upset yourself. But can I ask you why you want a white doctor? Tara told me you asked for a white foster carer. Is there a reason?’ I was starting to wonder if this was a form of racism, in which case I would find Zeena’s views wholly unacceptable.

She was looking down and chewing her bottom lip as she struggled to find the right words. Tara was waiting for her reply too.

‘It’s difficult for you to understand,’ she began, glancing at me. ‘But the Asian network is huge. Families, friends and even distant cousins all know each other and they talk. They gossip and tell each other everything, even what they are not supposed to. There is little confidentiality in the Asian community. If I had an Asian social worker or carer my family would know where I was within an hour. I have brought shame on my family and my community. They hate me.’

Zeena’s eyes had filled and a tear now escaped and ran down her cheek. Tara passed her the box of tissues I kept on the coffee table, while I looked at her, stunned. The obvious question was: what had she done to bring so much shame on her family and community? I couldn’t imagine this polite, self-effacing child perpetrating any crime, let alone one so heinous that she’d brought shame on a whole community. But now wasn’t the time to ask. Zeena was upset and needed comforting. Tara was lightly rubbing her arm.

‘Don’t upset yourself,’ I said. ‘I’ll make an appointment for you to see my doctor.’

She nodded and wiped her eyes. ‘Thank you. I’m sorry to cause you so much trouble when you are being so kind to me, but can I ask you something?’

‘Yes, of course, love,’ I said.

‘Do you have any Asian friends from Bangladesh?’

‘I have some Asian friends,’ I said. ‘But I don’t think any of them are from Bangladesh.’

‘Please don’t tell your Asian friends I’m here,’ she said.

‘I won’t,’ I said, as Tara reached into her bag and took out a notepad and pen. However, it occurred to me that Zeena could still be seen with me or spotted entering or leaving my house, and I thought it might have been safer to place her with a foster carer right out of the area, unless she was overreacting, as teenagers can sometimes.

Tara was taking her concerns seriously. ‘Remember to keep your phone with you and charged up,’ she said to Zeena as she wrote. ‘Do you have your phone charger with you?’

‘Yes, it’s in my school bag in the hall,’ Zeena said.

‘Will you feel like going to school tomorrow?’ I now asked – given what had happened at school today I thought it was highly unlikely.

To my surprise Zeena said, ‘Yes. The only friends I have are at school. They’ll be worried about me.’

Tara looked at her anxiously ‘Are you sure you want to go back there?’ We can find you a new school.’

‘I want to see my friends.’

‘I’ll tell the school to expect you then,’ Tara said, making another note.

‘I’ll take and collect you in the car,’ I said.

‘It’s all right. I can use the bus,’ Zeena said. ‘They won’t hurt me in a public place. It would bring shame on them and the community.’

I wasn’t reassured, and neither was Tara.

‘I’d feel happier if you went in Cathy’s car,’ Tara said.

‘If I’m seen in her car they will tell my family the registration number and trace me to here.’

Whatever had happened to make this young girl so wary and fearful, I wondered.

‘Use the bus, then,’ Tara said, doubtfully. ‘But promise me you’ll phone if there’s a problem.’

Zeena nodded. ‘I promise.’

‘I’ll give you my mobile number,’ I said. ‘I’d like you to text me when you reach school.’

‘That’s a good idea,’ Tara said.

There was a small silence as Tara wrote, and I took the opportunity to ask: ‘Zeena, do you have any special dietary needs? What do you like to eat?’

‘I eat most things, but not pork,’ she said.

‘Is the meat I buy from our local butchers all right?’

‘Yes, that’s fine. I don’t eat much meat.’

‘Do you need a prayer mat?’ Tara now asked her.

Zeena gave a small shrug. ‘We didn’t pray much in my family, and I don’t think I have the right to pray now.’ Her eyes filled again.

‘I’m sure you have the right to pray,’ I said. ‘Nothing you’ve done is that bad.’

Zeena didn’t reply.

‘Can you think of anything else you may need here?’ Tara asked her.

‘When you visit my parents could you tell them I’m very sorry, and ask them if I can see my brothers and sisters, please?’

‘Yes, of course,’ Tara said. ‘Is there anything you want me to bring from home?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘If you think of anything, phone me and I’ll try to get it when I visit,’ Tara said.

‘Thank you,’ Zeena said, and wiped her eyes. She appeared so vulnerable and sad, my heart went out to her.

Tara put away her notepad and pen and then gave Zeena a hug. ‘We’ll go and have a look at your room now before I leave.’

We stood and I led the way upstairs and into Zeena’s bedroom. It was usual practice for the social worker to see the child’s bedroom.

‘This is nice,’ Tara said, while Zeena looked around, clearly amazed.

‘Is this room just for me?’ she asked.

‘Yes. You have your own room here,’ I said

‘Do you share a bedroom at home?’ Tara asked her.

‘Yes.’ Her gaze went to the door. ‘Can I lock the door?’ she asked me.

‘We don’t have locks on any of the bedroom doors,’ I said. ‘But no one will come into your room. We always knock on each other’s bedroom doors if we want the person.’ Foster carers are advised not to fit locks on children’s bedroom doors in case they lock themselves in when they are upset. ‘You will be safe, I promise you,’ I added.

Zeena gave a small nod.

Tara was satisfied the room was suitable and we went downstairs and into the living room where Tara collected her bag.

‘Tell Cathy or phone me if you need anything or are worried,’ she said to Zeena. I could see she felt as protective of Zeena as I did.

‘I will,’ Zeena said.

‘Good girl. Take care, and try not to worry.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.