Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

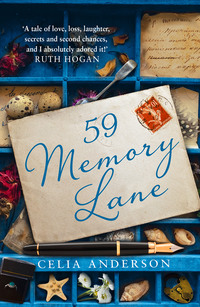

Kitabı oku: «59 Memory Lane», sayfa 2

‘Well, age is only a number, as they say, and I know Andy’s been worried that May can’t get out of the house now. Julia, the thing that really bothered me – well, it doesn’t sound much when you say it out loud, I suppose – it’s just that when I came down to fetch my car yesterday, she was just staring out to sea.’

‘Ida, lots of people like looking at the sea. I do myself. It’s very relaxing watching the waves. That doesn’t mean she needs adopting.’

Ida frowns. ‘I knew it was going to sound silly. I don’t use my car all that often but the other day when I called to get it to go to Truro she was doing exactly the same thing. Sitting on the decking just … staring … with such a sad look on her face.’

‘I still don’t think—’

‘And then as soon as she saw me both times, she started to chat about the weather, as if she’d been dying for somebody to talk to. May’s never been one for small talk. You know that as well as I do.’

‘But …’

Ida holds up a hand. ‘Yes, yes, I know you two have got history, as they say. An even better reason for you to get together over a nice cup of tea and let bygones be bygones.’

‘You think so?’

‘I do wish you wouldn’t purse your lips like that, Julia. You remind me of my mother, and she could be quite terrifying at times. It’s for a good cause. The scheme’s going well so far.’

‘Is it really?’

‘Oh, yes. You’d be surprised how many people in the village need a bit of company, but will they ask? No, they won’t. Too proud, or something … So, the story so far is that Vera from the shop’s adopted that nice old lady from Tamerisk Avenue. You know – Marigold – the one with the mobility scooter and the smelly Pekinese that rides in the basket?’

‘But Marigold’s got six children and any number of grandchildren.’

‘And when was the last time you saw any of them in the village? They only turn up when they want to cadge money off her. She barely sees a soul from one week to the next.’

‘I don’t think—’

‘And George and Cliff have really come up trumps. They’ve taken two for me. Joyce Chippendale, the retired teacher who’s registered blind, and the old boy from the last fisherman’s cottage on the harbour?’

‘Old boy? You surely don’t mean Tom King? He’s younger than me. He must only be in his late seventies.’

‘Well, yes, but he doesn’t get out much since he retired. Being a psychiatrist all those years took all his time up so he hasn’t really got any hobbies, and he looks as if he could do with a square meal. George is going to bring them both over for lunch or dinner at their restaurant a couple of times a week.’

‘How kind.’ Julia shivers. She knows this cannot end well.

‘I want to get other villages involved if this takes off. It’s a huge problem, Julia.’

‘What is?’

‘Loneliness, dear. But listen to me being tactless; I don’t need to tell you that, do I?’

Julia gives Ida one of her special looks, the kind she used to use to quell unruly Sunday school children years ago. ‘And what’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Well, with you losing Don, and everything. You must be lonely nowadays … with your family so far away …’ Ida’s voice trails off as she finally senses Julia’s icy disapproval.

‘Missing somebody isn’t the same thing as being lonely, Ida,’ says Julia, making a valiant attempt not to punch the interfering old busybody. Violence isn’t her thing, but she’s never felt more like doing somebody a damage. The cheek of the woman! Ida’s only about sixty and she’s still got a perfectly healthy husband, even if he is a bit dull. Who is Ida to make judgements about Julia’s needs?

Ida falls silent for a moment and then rallies. ‘Yes, you’re probably right. No offence meant, and none taken, I hope?’

‘Perish the thought.’

‘Oh, good. I’m going to ask Tristram to join the scheme next. If George and Cliff are doing it, he’ll not be able to resist. The two main fish eateries round here – Cockleshell Bay and Tris’s Shellfish Shack – both giving away meals for charity? It’s a great story. I’ll get the local paper onto it as soon as it’s really up and running. But first I’m going to call a meeting for us all.’

Julia waits, holding her breath. Sure enough, here comes the blow.

‘So, anyway, I thought Andy could bring May over tomorrow? About tea time?’

The words ‘Resistance is useless’ spring to mind. Whatever Julia says, Ida will steamroller over her. She squares her shoulders. No, she mustn’t be browbeaten. Ida can’t make her invite May over to visit, can she? It’s Julia’s house and she just won’t allow it.

‘I can’t have visitors at the moment,’ she says. ‘It’s completely out of the question. I’m sorry, but you’ll have to find someone else.’

Ida leans forward and looks into Julia’s eyes earnestly. Her chins are quivering with emotion. ‘But, Julia, don’t you think it’s our duty to do what we can for one another?’

‘Well, yes, but—’

‘That’s settled then. I’ll go and see May as soon as I leave here and let her know. She’ll be thrilled to bits, I’m sure. Tomorrow it is!’

Julia opens her mouth to argue again and then decides it’s pointless.

‘Are you rushing off to see May immediately?’ she asks.

‘Not when you’ve gone to the trouble of putting the kettle on for me. And isn’t that your famous fruitcake I see there? May will enjoy a slice of that tomorrow, too.’

‘If she comes.’

‘But why wouldn’t she? I’m sure May will be delighted to get out of the house and have a lovely chat with you.’

Julia says nothing. There are one or two excellent reasons why May might avoid visiting 60 Memory Lane, but she’s not about to share them with Ida.

Chapter Three

Across the road half an hour later, May glares at Ida as her visitor takes the last chocolate biscuit from the plate that Tamsin fetched from the larder. Andy has taken his daughter home now – he escaped as soon as he made the two ladies a fresh pot of tea.

‘I really shouldn’t,’ says Ida, munching happily, ‘because I’ve just started going to that slimming group in the village hall and it was all going so well until I had to eat some of your lovely neighbour’s fruitcake.’

‘Lovely neighbour? Which one’s that then?’

‘Now, now. You know very well who I mean. Julia sends her love.’

‘Really?’ May frowns. It doesn’t sound likely. Sending love to May wouldn’t be on that one’s priority list. After the incident with the missing soup spoons, they’ve never been more than civil. The very cheek of the woman, insinuating that May had pinched a whole bunch of tatty cutlery. She’d had enough trouble pocketing the sugar tongs. Of course, the real damage was done while Charles was still alive. Julia never liked May’s husband. Not many people did, come to think of it.

Ida’s eyes are shining with goodwill. She’s always had this annoying habit of thinking everyone should be fond of each other just because they live in the same village, thinks May. Most of them do get on, but May prefers to choose her friends for herself.

‘Yes, of course she sent her love – why wouldn’t she? Julia speaks very highly of you.’

‘She does?’

‘Not only that, but she’s asked me to see if you’d like to pop over there for a visit tomorrow.’

‘Are you pulling my leg, Ida? Why would Julia suddenly want me to go and see her? We haven’t spoken a word to each other since Don’s funeral, and that was only in passing. Anyway, I don’t get out of the house on my own these days. I’d end up flat on my face on the cobblestones.’

Ida smiles. There’s something of the shark about her when she’s got an idea in her head. ‘That won’t be a problem. I’m sure Andy will take you across the road when he finishes work.’

‘But—’

‘Now, there’s no need to worry. He’s working in my own garden tomorrow, as luck would have it, so I can make sure he gets home in good time. Julia’s expecting you at half-past five. And if you’re lucky, she might show you some of her treasure trove. I’ve never seen so many old letters in my life.’

May is silent. Of course! Why hadn’t she thought of this before? She should have snapped Ida’s hand off straight away. Those letters. All the memories just waiting for her. Can it be that her prayers have been answered? She’s never been sure about God, but it doesn’t hurt to hedge your bets, and she always likes to send up a few requests while she’s listening to the Sunday morning hymns on the radio.

Some of the words to the hymns are quite poetic, and she sings along with gusto. Her favourite is the wedding one. She likes the lines:

Grant them the joy which brightens earthly sorrow,

Grant them the peace which calms all earthly strife.

It paints such a lovely picture of marriage. Hers wasn’t at all like that, especially after May found Charles in bed in the middle of the morning with the baker’s delivery boy, if you could call a strapping nineteen-year-old a boy, but there’s no need to be cynical about the institution in general.

She rustles up a big smile for Ida. ‘Well, it sounds as if you’ve got it all sewn up,’ she says. ‘But I still can’t see why Julia would choose to invite me over? In truth, Andy told me he was anxious because she wasn’t seeing anyone at the moment. She’s turned into a bit of a hermit.’

‘I know, and it’s been a worry to us all. She hasn’t been to the morning service for months. She’s taken Don’s death very hard. They were true soul mates, weren’t they?’

May presses her lips together. She’s always hated that expression. As if souls could talk. If that was the case, there’d be a lot fewer arguments and misunderstandings in the world. Her own husband wasn’t so much of a soul mate as a pain in the backside, especially in the later days, when he had dark suspicions about his health issues. If only he’d had the sense to see the doctor. After Charles died she began to appreciate his finer points again, but while he was with her the temptation to smother him was sometimes almost irresistible, the awkward sod. Pedantic, waspish and far too fond of flower arranging.

Ida’s peering around the room now. Nosy old bat. ‘You’ve got some lovely ornaments and pictures,’ she says. ‘It’s hard to imagine how anything can be around so long and yet still be so perfect.’

‘Like me,’ says May, with a cackle.

Ida smiles. ‘You’re absolutely right. Everyone always says how young you look, May. How do you do it? What’s your secret? Do you use some sort of fancy face cream?’

‘You must be joking,’ says May. ‘I wouldn’t spend good money on that muck. No, my looks are down to a small daily dose of port and brandy, plenty of heathy food and clean living, that’s all.’

May has trotted this mantra out so often that she might almost believe it if she didn’t know the truth. When she first realised that it was possible to pick up vibrations from certain objects, or whatever she liked to call the effect that she got, May was young enough to think that all children got a sparkly feeling of wellbeing when they touched things that had an interesting past. It took quite a while to match her magical moments to the treasures she sometimes managed to collect by trawling the local jumble sales and junk shops with her mother.

Pocket money didn’t go far when you were an avid collector, but her father seemed to understand her needs better than her mother, and if he took her out shopping he would indulge her by slipping a bit of extra cash into her pocket at vital moments. And when May realised how many people in the village had memories hidden away in their possessions, the harvesting really began to move into gear. A special, secret sort of magic, that’s what it is, and it needs to stay that way.

She remembers the first time she was overcome by the feeling that she must have something precious that didn’t belong to her, even though, at ten years old, she knew very well it was wrong. May’s mother took her to their nearest neighbour’s house for tea, and while the two ladies were busy in the kitchen May spied a tiny enamelled box with a tightly fitting lid. She picked it up and cradled it in the palm of her hand. Patterned with purple violets, the box seemed to hum to itself, as if it had secrets that only May could hear.

May prised off the lid with a fingernail, all the while listening in case the grown-ups came back. Inside was a curl of hair, soft and blond. May held her breath and put her finger into the middle of the hair. The warmth and energy that flowed from it was so dramatic that she withdrew her hand with a gasp. After a moment, she tried again, preparing herself this time. Bliss. Glancing over her shoulder, May slid the curl into her pocket, then closed the lid and returned the box just as her mother reappeared carrying a plate of fairy cakes.

Since that day, there have been many other chances to find what she needs, but May has had to be careful. Now and again she’s come very close to being caught.

Unaware of the unsettling thoughts racing through May’s mind, Ida checks her watch and gets to her feet, accidentally treading on Fossil, who hisses his disapproval and runs for the cat flap. ‘Whoops! Sorry, cat. So that’s settled then. Andy can fetch you as soon as he’s finished at mine. I’m very excited about this new scheme, May. It’s going to benefit so many people. Poor Julia is so lost nowadays, and you’ll get a lot out of it, too.’

‘Oh, yes, I do hope so,’ says May.

A tiny bubble of excitement shivers inside her. She’d better take her largest handbag when she goes across the road tomorrow.

Chapter Four

Andy calls for May the next afternoon on the dot of half-past five. She is wearing her best dress, which is cornflower-blue, and a pair of low-heeled court shoes in honour of the occasion. She’s not about to let Julia think she’s gone to seed while she’s been stuck in the house. The dress is sprigged with tiny buttercups and daisies. It makes May think of the rolling meadow behind her old home up the hill. She sighs. Oh, well, no point in looking over her shoulder – a beach on your doorstep is worth a dozen grassy fields and woods, after all. You couldn’t see the sea properly from the big house even though it was high up on The Level because the trees in between blocked the view.

Andy gives an impressive wolf whistle when he sees her. ‘Blimey, May. You still scrub up well. You don’t look a day over seventy.’

She bats him with her handbag and turns to the hall mirror to tidy her already immaculate hair. She’s always been glad that when the rich auburn of her hair eventually began to fade, it turned a beautiful snowy white. May misses being a foxy redhead sometimes, but her hairdresser thinks she’s very glamorous and calls every Monday to wash and set May’s curls in the usual bouffant waves. No blow-drying for May – she sticks to her faithful sponge rollers. A hefty squirt of hairspray and she’s ready for the week. The style hasn’t changed for years – why should it?

‘Pass me my lipstick, please, Andy. It’s on the side there. And the perfume. You can’t go wrong with Je Reviens, I always say. Thank you. Don’t want to let the side down, do I?’

He laughs, and offers May his arm as they head out of the door and down the uneven steps. She holds on tightly to Andy as they go over the cobbles, wobbling on the unfamiliar heels, and breathes a sigh of relief when they’re safely on the other side of the narrow lane. The breeze is fresher today, and May can see several small boats bobbing around near the harbour over to the right of the beach. There’s a strong smell of salt and seaweed in the air, and her heart lifts. It’s good to be outside and going somewhere for a change. The garden’s all well and good, but May misses being in the thick of things.

‘Come on then, May,’ says Andy. ‘We’d better not keep Julia waiting any longer. I usually go around the back and let myself in, but we’ll do it the proper way today as this is a special occasion.’

May rolls her eyes but makes no comment. Julia opens the door almost before they’ve rung the bell.

‘Hello, May. It’s good to see you,’ she says, but her smile doesn’t reach her eyes, and May isn’t fooled.

Andy helps May inside and Julia pushes a high-backed chair forward so that May can lower herself to a sitting position using the chair’s arms to support her. As May glances up, cursing herself for this new sign of weakness, she sees a look of pity on Julia’s carefully made-up face. May seethes inside but puts on her best party expression. There’s a lot to play for here.

Julia’s wearing an elegant grey shift dress, beautifully cut but rather grim, with a single string of pearls to finish the look. Well, her neighbour’s gone to the trouble of smartening herself up as usual, thinks May, but her blood boils at the realisation that Julia is feeling sorry for her. She’s filled with an even stronger resolve to get hold of at least one of Julia’s letters today. If she can soak up even a few memories, she’ll begin to feel better again. It’s been too long.

‘I’ll get going then, girls,’ says Andy. ‘Tamsin’s at Rainbows up at the church hall and I need to pick her up soon and get her home for tea. See you later.’

‘Bye, love,’ says May, taking the opportunity to look round the room as her neighbour sees him out. There are a few heaps of letters on the table. She must have interrupted Julia in her sorting. Good.

‘So, a cup of tea, May? I’ve made some scones for us,’ says Julia, coming back in. It’s a spacious, light room, with a dining table at one end and French windows opening onto a view of the other end of the cove. May can’t see this part of the world from her windows, and it’s a refreshing change to look out towards Tristram’s long, low bungalow and restaurant on the headland. It’s a while since she’s had the chance to eat at The Shellfish Shack.

Tristram’s an old friend and an attentive host, and the food there is sublime. May wonders how much a return trip in a taxi would be. It doesn’t seem long since she was able to walk there from her old home. But as soon as she gets hold of some new memories, her energy will come flooding back. There’s no time to lose. The alternative doesn’t bear thinking about.

Julia pushes the letters out of the way to make room on the table for their afternoon tea before she bustles off to the kitchen. ‘Jam and cream on your scone, May?’ she calls.

‘Yes, please. Jam first, obviously. Is it your own?’

‘Oh, yes. The last of the blackberry jelly from last year. Don loved it.’

There’s a silence as May remembers Don’s boyish glee whenever he was offered anything sweet to eat. Julia isn’t clattering around the kitchen any more, although May can hear the kettle boiling. Maybe she’s blubbing in there. May wonders if she should go in and offer some sort of comfort but she’s never been very good at hugging and so forth, and anyway, Julia would probably dig her in the ribs or poke her in the eye if she attempted anything like that. While she’s trying to decide what to do, Julia comes back in with a loaded tray. Her eyes are a bit pink but there’s no sign of tears. May heaves a sigh of relief.

They sit and eat their scones in silence for a few moments. ‘You haven’t lost your touch, dear,’ says May, reaching for a paper napkin to wipe away the last crumbs.

‘I haven’t made much cake of any sort since … well, you know. It’s no fun baking for yourself, is it?’

‘Haven’t you had your family over to see you, then?’ May doesn’t really need to ask this as she knows Felix and Emily haven’t visited lately. She’s more than aware of any comings and goings around her new neighbours’ houses. There’s nothing else to do these days but people-watch, so she’s sure Julia’s son and granddaughter haven’t been near the place since Don’s funeral last November.

Julia sits up straighter. She drinks her tea and seems to be searching for the right words. ‘They’re very busy,’ she says, ‘and of course Emily’s still working in New York, so she doesn’t get over here very often. Her mother has settled somewhere beyond Munich, out in the sticks, you know. She was always banging on about going back to her homeland, so Emily has to put visiting Gabriella at the top of her list when she gets time off. They booked tickets for me to fly over to Germany for Christmas but I had to cry off at the last moment … sadly.’

‘What a shame.’ May heard this news from Andy at the time and remembers that Julia was ill, although Andy wasn’t convinced that a slight chill should have made her miss all the festivities. May suspects that Julia’s feelings about family Christmases are as lukewarm as her own.

‘And Felix?’ May probes. She’s been wondering if the old feud is still simmering. Felix’s wife managed to cause quite a rift between her husband and his parents, before she upped and left with the owner of a Bavarian Biergarten, and even the mention of Gabriella’s name has put a chill in the air.

Julia shrugs. ‘He’s still based in Boston but he travels all over the world. Business is booming, as they say. I expect he’ll be here soon. It’s my birthday at the end of next month.’

Julia’s eyes fill with tears and May’s heart sinks. She remembers the loneliness of birthdays after Charles died. He wasn’t very good at presents and fuss, but at least he always took her out for a decent pub lunch at the Eel and Lobster on the green. Charles loved a nice plate of scampi and chips, and May always went for a home-made pasty with heaps of buttery mashed potato. It’s well over fifty years since May’s husband went voyaging and didn’t come back. There were whispers of suicide amongst the villagers but the official view was accidental death, due to the storm that suddenly whipped up. Eventually, the remains of Charles’s boat were found near to the harbour and his body was washed up on the next tide after that.

Charles was much too experienced a sailor to make such an obvious error of judgement; everyone who knew him must have been aware of that fact. He was many things, but reckless wasn’t one of them. Although May was surprised at the verdict, she held her tongue. It was easier that way.

May let the dust settle after the inquest and kept a low profile for a while. Life without Charles seemed strange, but soon became the norm. They didn’t marry until they were in their forties, soon after May’s parents died. At the time May felt unusually lost, cut adrift from her comfortable routine, and moving Charles in seemed like a logical step for them both. They had been together for only eleven years when the tragedy happened so May’s used to being alone now, but she can see that Julia has got a long way to go before she reaches that sort of self-sufficiency.

‘Come on, don’t cry,’ says May, patting Julia’s hand awkwardly. ‘You had a good life with Don. Nothing lasts for ever in this world.’ Or does it? she thinks. Maybe if I can get more memories, it might.

Julia is looking at May with deep loathing now and she realises she’s said the wrong thing.

‘That’s not the point,’ Julia mutters.

‘Well, it is really, dear,’ says May, pulling a face and reaching for her teacup, ‘but with hindsight I can see why today might not be a good day to say it.’

Julia’s mouth twitches, and then she laughs long and hard – a great guffaw that’s most unlike her. ‘Oh, May – you’re a real one-off,’ she says, wiping her eyes.

The sudden connection between them doesn’t last for more than a few seconds but after that, the time passes quickly. They talk about their neighbours’ foibles and the arguments at the stark grey Methodist Church about the new minister’s penchant for long sermons and soppy new hymns, and it’s not until Andy knocks on the back door to announce his arrival that May realises she hasn’t even tried to smuggle a letter into her handbag.

Julia goes to the kitchen to meet Andy, and May stands up, swaying slightly. If she leans over, she can reach the pile on the table. She holds onto her chair back with one hand and takes an envelope at random, slipping it into her handbag. It feels like a good one – quite thick, and there’s a buzz just from holding it. Her heart flutters. She thinks about taking a second letter but the voices are coming closer. She zips up her bag just in time, as Julia and Andy come in, followed by Tamsin, still wearing her Rainbow uniform.

‘All talked out, ladies?’ Andy asks. ‘Ready for the off, May? Tamsin needs her bath; they’ve been clay modelling tonight, and she’s a bit grimy. And she’s wearing most of her tea. It was spaghetti. I think I overdid the sauce.’

‘I don’t need a bath. Clay doesn’t smell bad,’ says Tamsin, but Julia takes her by the shoulders gently and guides her in front of a long mirror. Tamsin giggles. She has a streak of clay all down one cheek and a lump of it buried in her curls, plus a hefty blob of tomato mush on her chin and around her mouth.

‘You’ll need your hair washing tonight, my pet,’ says Julia, and Andy throws her an agonised look. May’s heard the noise from the bathroom on shampoo nights. It’s even worse than the ponytail protests.

May is ready now. She doesn’t meet Julia’s gaze as she leaves the room. The brief burst of warmth between the two of them has dissipated, and the tantalising letter is tucked snugly inside May’s bag. She can’t wait to tap into its memories.

It doesn’t take long for Andy to get May home and settled in her favourite chair, with Fossil rubbing around her ankles.

‘Shall I make you a sandwich?’ Tamsin says. It’s her latest skill. She can only do ham or jam so far but she’s building up to cheese. It’s the cutting that’s tricky. ‘I’m getting better at the buttering bit now,’ she adds hopefully. ‘There’s not so many holes.’

‘No, you get back home and get into bed when you’ve had that bath. I’m full of Julia’s scones, thanks.’

May hears them go, with Fossil following just in case there’s any fish going spare at Andy’s. Her bag is on her knee before they’ve even had time to cross the gap and go through the gate between Shangri-La and their terraced house. She fumbles for the letter, fingers made clumsy by urgency. As she pulls the faded blue sheets from their envelope, the familiar buzzing begins and she sighs with relief. It’s happening. She hasn’t lost the knack of tapping into the precious memories.

For a little while, it’s enough just to hold the pages in her hand and feel a warmth spreading through her body. It builds slowly: a tingling, effervescent shimmer of hope, cascading into ripples of delight. May wriggles blissfully. This is what she’s been missing so desperately. On one level, she’s still in her cosy living room hearing the cry of the gulls and the faint sound of Tamsin pushing the cat back in through the flap in the kitchen door and telling him it’s nearly bedtime. On the other hand, she’s floating above the room, high on a wave of wellbeing and happiness.

It’s the lifeblood, flowing into her veins. The power to stay young, or at least to slow the march of time. One hundred and eleven is surely going to be possible now. Eventually, May feels the intensity of the memories ebbing, and reaches for her glasses as Fossil jumps up to settle on her lap. Pulling out the closely written sheets, she sees Kathryn’s name on the final page.

As she begins to read, cascades of tiny bubbles dance through her narrow frame and she has to stop every few sentences to catch her breath.

We’ve just had a newspaper cutting from our Nottingham family telling us of Pauline’s engagement! Quick work, what? I bet her engagement ring isn’t as good as Mother’s. Opals take some beating, especially three such beautiful stones – and the tiny diamonds around them are so pretty too. If only we could find it. Mother’s heartbroken. She’s started behaving very oddly, accusing each one of us in turn of hiding it. As if we would. We all know how much she wants Julia to have the ring. Will’s very upset about it all. Has he written to you lately? That boy gets more and more secretive the older he gets, it seems to me.

May leans back in her chair. After months of memory-deprivation this is almost too much.

She recalls the large, noisy family and their visits very well. Charles was quite chummy with Don’s relatives for a while. He used to take them out in his boat.

It’s time to put the letter away for the night, even though the mystery of the ring is intriguing. Perhaps there will be more clues in the later ones. May’s sure Julia has never had a ring like the one Kathryn describes.

May is lost in echoes of the past now, and thinking of Kathryn puts her in mind of another girl from long ago, with the same name but spelled differently. She reaches over to fetch a dusty book from a low shelf, and sniffs the musty fragrance happily as the pages fall open at her favourite entry.

May’s old school friend Catherine was what they used to call ‘a card’. She loved making up silly rhymes, usually about their teachers, leaving them around for people to find at the most inopportune moments. Catherine really came into her own during a fad for collecting autographs that swept the girls’ grammar school. These weren’t in the modern trend of finding famous people to write in your autograph book, but merely a way of proving how many friends you had by letting them fill the pages with trite, jokey and sometimes rather rude messages.

When May passed Catherine her own precious leather-bound book, she hoped that the other girl wouldn’t write anything that her parents shouldn’t see. She was relieved to read a poem that was more thoughtful than Catherine’s usual doggerel and reminded her of her father’s words about living to the ripe old age of one hundred and eleven when he’d gazed at that beautiful sunset so long ago. Coincidence? May has never believed in them. This was surely a sign. The poem was entitled ‘My Years With You’, and read: