Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Most Difficult Thing»

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Charlotte Philby 2019

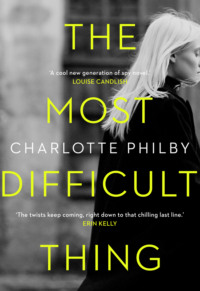

Cover design by Andrew Davis © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Elena Alferova / Trevillion Images

Charlotte Philby asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008326982

Ebook Edition © June 2019 ISBN: 9780008327002

Version: 2019-06-03

Dedication

For Rosa

Epigraph

‘To know yourself is the most difficult thing’

Thales of Miletus

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1: Anna

Chapter 2: Anna

Chapter 3: Anna

Chapter 4: Anna

Chapter 5: Anna

Chapter 6: Anna

Chapter 7: Anna

Chapter 8: Anna

Chapter 9: Anna

Chapter 10: Anna

Chapter 11: Anna

Chapter 12: Anna

Chapter 13: Anna

Chapter 14: Anna

Chapter 15: Anna

Chapter 16: Maria

Chapter 17: Maria

Chapter 18: Maria

Chapter 19: Maria

Chapter 20: Maria

Chapter 21: Maria

Chapter 22: Maria

Chapter 23: Anna

Chapter 24: Anna

Part Two

Chapter 25: Anna

Chapter 26: Maria

Chapter 27: Anna

Chapter 28: Anna

Chapter 29: Anna

Chapter 30: Maria

Chapter 31: Anna

Chapter 32: Anna

Chapter 33: Maria

Chapter 34: Anna

Chapter 35: Maria

Chapter 36: Anna

Chapter 37: Anna

Chapter 38: Maria

Chapter 39: Anna

Chapter 40: Maria

Chapter 41: Anna

Chapter 42: Anna

Chapter 43: Maria

Chapter 44: Anna

Chapter 45: Maria

Chapter 46: Anna

Chapter 47: Maria

Chapter 48: Anna

Chapter 49: Maria

Chapter 50: Anna

Chapter 51: Maria

Part Three

Chapter 52: Anna

Chapter 53: Anna

Chapter 54: Maria

Chapter 55: Anna

Chapter 56: Anna

Chapter 57: Maria

Chapter 58: Anna

Chapter 59: Anna

Chapter 60: Maria

Chapter 61: Anna

Chapter 62: Anna

Chapter 63: Maria

Chapter 64: Anna

Chapter 65: Maria

Chapter 66: Anna

Chapter 67: Maria

Chapter 68: Anna

Chapter 69: Maria

Chapter 70: Maria

Chapter 71: Anna

Chapter 72: Maria

Chapter 73: Anna

Chapter 74: Maria

Chapter 75: Anna

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

I felt my abdominal muscles twinge as I lowered myself to sit. The bench by the lamp post at the foot of the bridge, just as planned.

It had been almost two months since the surgery but still the scar was so raw that I felt tearing across my abdomen if I so much as lifted one of the twins at the wrong angle. Letting my eyelids drop for a moment, I pushed the thought of the girls out of my mind.

Open the box, close the box. Just as the doctor had taught me.

They were not so much benches that lined the stretch of pavement along this part of the Thames. More slabs, like a procession of concrete coffins quietly guarding the water.

It was dusk. Winter. The terminal gloom had long set in, and with it the sort of damp cold that gnawed its way into your bones. A thin gust of wind snuck through the opening in my cardigan as I pulled the grey cashmere closer across my breasts, still swollen.

‘For God’s sake, Harry,’ I cursed him silently, my eyes rolling up towards the stone-coloured sky.

For as long as I can remember, I have always been early. It is a pathological politeness that brings with it control; no one wants to be the last person to step into a room. It was one of the things we shared, at the beginning, he and I. How many times had I arrived early to meet him, before all this had started, only to find him already lurking under an amber glow at the end of the bar?

Yet it was nearly five, and the pavement around me was virtually empty but for a steady stream of deflated tourists and office workers scuttling towards the Tube.

What was he playing at? David would be home from work by six, as had been his wont since the babies had arrived and, almost overnight, he too had been reborn, his naturally attentive, easy parental love a reminder of everything I could never be.

I had told Maria I was just going shopping for babygros. What was Harry doing? Careful not to make any sudden movements, which I had come to accept would be followed by a sharp stab of pain, I pulled my phone from my navy leather handbag, my hand trembling.

No new messages.

My fingers were a bluish-red. I had hardly left the confines of the house since the birth, two months ago, aside from those ritualistic processions along the darker recesses of Hampstead Heath, under the instruction of the nanny. The Nanny. The truth was, she was always so much more than that. Ever-competent Maria silently heaving the double buggy down the front steps, seeing me off from the shadows of the doorway.

I loved the way the air chilled my lungs. Even the buildings on Millbank, which loomed over us from the other side of Lambeth Bridge, seemed to shiver. I had forgotten how cold it got out here. How easy it is to forget.

Hoping I’d maybe missed something in the string of messages that had passed between Harry and me, I flicked my fingers across the screen. Nothing. How many times had I reread his messages? How many times had I crept across the hallway while the girls slept, my toes curling into the carpet, sliding the lock closed behind me, carefully retrieving the phone from where I kept it, stuck behind the drawer of the cupboard where the bathroom cleaning products were kept – somewhere I could guarantee David would never look?

Telling myself I would wait five more minutes before considering my next step, I flicked through a stream of encrypted messages. Once again, my attention was caught by a single image: a photograph, blurred, but clear enough – my father-in-law, the grandfather of my children, shaking hands with a man in a dark suit – his thick black beard a smear of tar across a smudge of flesh.

Out of the corner of my eye I noticed the streetlights flick on along the river. Looking up, I saw him. Those fierce blue eyes drilling a hole in my chest. Breathing sharply, as if struck, I said his name: ‘Harry.’

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

Anna

Three Years Later

The house is still, as it always is at this hour. Once again, I have hardly slept, taking a moment to savour the peace, the calm before the storm: this moment in which I am neither who I was nor who I will become. My eyes skitter across the silver clock by my bed, the one that had belonged to David’s mother: 5.40 a.m. 1 May. The date is already firmly etched in my mind, as it will be for as long as I live.

Dawn has always been my favourite time of day. As a child I would wander the narrow hall of my parents’ house under a hazy bruise of light, gazing through the window overlooking a cul-de-sac of privets and exhaust pipes, imagining myself somewhere else.

David is still asleep. I sit, slowly, careful not to rouse him, his body a mound of flesh under a blanket of Marimekko florals.

I have spent most of the night going over the plan in my head, sealing every second of it into the recesses of memory, ensuring it could never be prised out again should I be caught. Caught. It’s not a word I allow myself to linger on too long.

Creeping from the bed, with its expensive linen sheets and tasteful throws, I sit at the stool in front of the small oak dressing table with its neat displays of family life. Trophies, trinkets of a world I have made my own. Among them, a bronze frame with a photo of David and me in front of the vista of his father’s house in Greece. One of many of his family’s boltholes that we have jetted between over the years, the planes leaving tracks like scars through the sky, visible only to those who glance up at just the right moment.

So young we were then, clinging to one another in front of the pool, the Greek sun bleaching out our features. David’s body turned towards mine, claiming me. Our first holiday together had been a victory, almost. This was where it all had really begun. I was his prize, he had said it a hundred times, but he never knew that he was also mine. Not yet, but he will.

The thought jars in my mind, and I lift my head, catching my reflection in the oval mirror. For a moment I am transfixed. The same light blonde hair, pale green eyes, high cheekbones. Hardened, now. The years of insomnia have caught up with me, in the hollows of my eyes. The corners of my mouth, cracked from years of fixed smiles.

My phone is plugged into the charger on the wall. Silently, I lift it, glancing at David’s sleeping body in the mirror – the soft line of which I could draw from memory – before tapping my password into a second phone, stashed in the pocket of my silk dressing gown. My fingers leave a streak of sweat across the screen. The phone is the same model, same sleek black cover as my other one. Same pin number – the date Harry and I first met. Fundamental differences you would have to peer inside to see.

Once again, I flick through a stream of messages from Harry, distracted for a moment by a chip in my blood-red nail polish. Hearing David stir in the bed, I expertly lock the phone while concentrating my face in the direction of the neat row of perfumes and creams in front of me, replacing it in the pocket of my gown as I stand.

‘What time is it?’

David’s voice drifts across the room, still thick with sleep.

‘Nearly six. My flight isn’t until twelve but I have work to catch up on; Milly’s off on maternity leave today.’

I picture my assistant, whose belly I have watched swell and groan under its own weight over the past months. I picture the young woman’s blotchy red cheeks, which she attempts, feebly, to mellow with slightly too-orange foundation; her increasingly uncomfortable gait.

Over the past weeks, I could almost feel her pelvic bones grating as she delivered proofs of the next issue of the magazine to my office.

Of course Milly believed she would be back within a few months of having the baby, four to six months’ maternity leave, she had told HR. I don’t believe it for a second. Not that it matters. Either way, I won’t be seeing her again.

‘I’m going to have a shower.’ David’s voice interrupts my thoughts.

Smiling convincingly back at him, I lay my hand on a pile of magazine pages, ‘Of course, I won’t be long with this.’

An hour later, I am standing by the door, ready to leave.

‘You look nice.’ David sweeps down the stairs, his polished brogues crushing against chenille carpet, nudging one of the girls’ scooters back in line against the wall in the hallway as he passes; the scooters he had insisted on buying them for their third birthday, a few months earlier, ignoring my concerns that they were too young.

I am dressed for the office. An Issey Miyake cream trouser suit fresh from the dry-cleaners. Shoulder-length hair tucked behind my ears. A slick of Chanel lipstick. The same perfume I spritz and step into every morning, the smell chasing me through the house, a reminder of who I am now.

It was what the papers always commented on, when a picture of me found its way into the society pages of some supplement or other. Perhaps they did not know what else to say: ‘Anna Witherall, editor wife of TradeSmart heir David Witherall, perfectly turned out in …’ Ethereal beauty. Enigmatic charm. These were the words they used. Lazy attempts to place a finger on my ability to stand out and disappear at the same time.

As David makes his way towards the open-plan kitchen – a wall of sliding glass at the back, lined with California poppies – I stand in the hall, making a show of the final check of my handbag. Inside my bag, my fingers are shaking.

Passport, keys, purse. Just another day.

‘I really think you should stay at Dad’s while you’re there, it will be much nicer than a hotel,’ David calls across the kitchen as I slip my feet into a pair of black leather mules, which stand side by side next to the girls’ shoes, Stella’s scuffed at the toe.

I feel the colour rise in my cheeks, and look down again so that he won’t notice. ‘Do you think?’

It is exactly what I have been relying on, of course. Knowing my husband as I do, I can predict that he will push for me to stay at his dad’s place; desperate for this connection to me, this ownership of my life, even when I am abroad.

‘There is actually a ferry, isn’t there, which runs directly from Thessaloniki to the island …’ I add casually, as if the thought has just occurred to me.

It takes four hours and fifty-five minutes, port to port. Not that I will be taking it, of course.

‘Honestly,’ I pace my words carefully, ‘your father won’t mind?’

David doesn’t look up from his newspaper. ‘I told you, he won’t be there, he won’t be in Greece for at least another month. I’ll send a message to Athena, tell her to make up the bed.’

Before I can answer I feel the phone purr in my pocket. I look down, keeping my breath light. WhatsApp message from Unknown Number.

Thinking of you.

Inhaling, I close my eyes before placing the handset in my bag along with my usual phone and house keys, and head into the kitchen, all tasteful teal cupboards and oak countertop. A chrome Smeg fridge plastered in naive children’s drawings, daffodils turning on the table, scattered with the detritus of breakfast.

Neatly dressed in matching pinafores, my daughters are slumped in their chairs, their eyes glued to the iPad their grandfather insisted on buying them. Their grandfather. The thought brushes against my knees and my legs bow. Feeling a rush of blood to my head, I place my hand on the countertop to steady myself, breathing deeply.

Looking up, I prepare to blame a stone in my shoe, a spasm of the spine, but no one has noticed.

This is it. I let my eyes shift between David, the competent father, and the girls. My girls. Still but not quite babies.

Something looms above them, a hint of the women they will become, the women I will never know. Rose’s left eye twitches as it always has when she is tired or worrying about something. Even now she is like a person with the weight of the world on her shoulders. A typical first-born, even if only by a minute. Stella, beside her, oblivious always. How long will she remain so? I feel the unwanted thoughts rise in my mind, and expertly push them down again, back into the pool of simmering acid in my gut.

‘Anna?’

I blink for a moment at the sound of my husband’s voice. How long have I been standing here?

‘I’ll get the door for you. Are you sure you don’t need a lift to the station?’ Is there a hint in his tone? Does he sense what is about to happen? For a second I wonder if I see something in his expression, but then I look again and it has gone.

Grateful for the distraction, I keep my voice light, though my lips are so dry I feel a sharp crack as they tighten. Keeping my hand steady, I shake my head and take a fresh slice of toast from David’s hand.

‘I’m sure.’

I thought it would really take something to kiss my children goodbye one morning and walk out the front door, knowing I wouldn’t be back. But in the end, it was simple. The door had already been opened; all I had to do was walk.

CHAPTER 2

Anna

There is no going back now. The taxi glides away from the house, down the street towards South End Green, retreating effortlessly from my family home, away from the expensive brickwork and tended gardens I will never see again.

The sound of the indicator clicks out a steady rhythm. My body quietly shaking, I turn my head so that my driver will not look at me and see what I have done, I watch my life streak past through the window, the bumping motion of the car, the low hum of conversation from the radio.

The girls hadn’t lifted an eye as the horn beeped from the road. Why should they? To them, today is just another day. How long will it be until they learn the truth? How long until the illusion of our lives together comes crashing down, destroying everything I have created, everything that I hold dear?

‘Why couldn’t he get out and ring the bloody doorbell?’ These were David’s parting words.

I have called a different cab service from my usual. My face is automatically drawn to the locks on the car door as the motor flicks silently to life, the wheels rolling between the parade of five-storey terrace houses, into the unknown.

Moving through South End Green, I am bemused by the familiar bustle of London life – the sound of discarded cans rattling against the gutter, the boys in bloomers and long socks stuffed into the back of shiny 4x4s, an old woman with an empty buggy pushing uphill against the wind – the world still rolling on as if nothing has changed.

The traffic is heavy. When the car turns off, unexpectedly, at Finchley Road, my hand grips the door handle.

‘Short cut.’

The voice in the front seat senses my fear but it does little to allay my nerves.

As the car turns, my eyes are distracted by the sudden movements of the trees, the light sweeping over the rear-view mirror. When it levels out again, I see the driver’s eyes trained on mine for a fraction of a second, in the reflection, the rest of his face obscured.

It is an effort to keep my legs steady as I step out of the car at the airport, every stride pressing against the desire to break into a run.

The terminal is a wash of blurred faces and television screens. Slumped bodies, caps tilted over eyes, neon signs, metal archways. My body endlessly moves against the tide, my eyes flicking left and right beneath my sunglasses. There is a sudden pressure on my shoulder and I spin around but it is just a rucksack, protruding from a stranger’s back.

There is something satisfying about flying, I find: the routine of it, the rhythm; answering questions, nodding in the right place, yes, shaking your head, no. I am grateful for it now – for the process, a welcome distraction from what will come.

Nevertheless, my mind won’t settle. All I can do is run through the plan once more. There will be hours of waiting at the airport before my flight to Skiathos. My time there will be brief, a night at the most, and from there I will travel on using the ticket I will buy in person at the airport, a day later, in my new name – the one emblazoned in the pages of the passport Harry had couriered to the office days earlier.

By the time I reach security, the urge to get to the other side is almost as strong as the desire to stay.

The queues this morning are sprawling. Breathing in through the nose, out through the mouth, as the doctors taught me, I remain composed, even when confronted by an abnormally cheerful security officer.

‘Going somewhere nice?’

For a moment, my mind flips back to this morning. From this vantage point, I watch what happens as if I am a witness – soldered to the sidelines, my tongue cut out. Unable to intervene, I watch myself leaning forward to kiss my daughters on their foreheads, lingering a second longer than usual. Neither had moved, barely raising their eyes from the iPad, which David had propped up against a box of cereal, a cartoon dog tap-dancing on the screen.

I watch the corners of their mouths twitch in unison, their spoons suspended in front of their faces, engrossed in their own private world. Behind them, the glass doors leading out to the garden that I would never see again.

‘I love you.’ Had I said it aloud? I had tried to catch my daughters’ eyes for a final time, my fingers curled tightly around the edge of the breakfast table. But they were lost in their own arguments by then, oblivious to what was happening before them.

Startled, I blink, lifting my eyes once again so that I am now focusing on her face.

‘Sorry, I …’ Breathing in, I remind myself to stay calm. There is no reason for her to question any of this.

‘Thessaloniki. It’s for work, I’m a writer. There’s an art fair, I’m interviewing one of the curators.’ It is an unnecessary detail and for a moment I curse myself, but the security officer has moved on, no longer interested.

It is a balance; truth versus lie. The tiny details are the ones that guide me through. Things can be processed in small parts, after all. But too much truth and the whole thing comes unstuck.

It is true that the magazine is intending to cover the Thessaloniki event, and I am lined up to write the piece. That way, if on the unlikely off-chance David had ever bumped into one of my colleagues and mentioned it, I would be covered. What David does not know is that the show is not due to start for another three days, and by then, I will be long gone.

Once I am on the other side, I quickly check for my original passport, which I will dispose of once I reach Greece. I head to WHSmith to buy a paper. I can’t concentrate but I need something that will help me blend in, distract my eyes.

Scanning the neatly compartmentalised shelves, my attention is drawn to the luxury interiors title of which I am editor. Was.

I remember how the office building seemed to swell up from the pavement, the first time I saw it. Entering the revolving doors off Goswell Road, turning left as instructed, the palm of my hand nervously pressing at the sides of my coat. Acutely aware of how young and unsophisticated I must have seemed, I had forced my spine to straighten, my consonants to harden.

The office, a wash of soft grey carpet and low-hanging pendant lights, a wall of magazine covers, was a picture of good taste, framed on either side by views of the city.

At first I had felt like an intruder, following the immaculately presented editorial assistant through the warren of desks scattered with leather notepads and colour-coded books. But then there was a wave of pride, too, that I might finally feel part of something.

It had been a struggle not to fall apart when Meg told me, with a blush of shame, that she had been offered the chance to stay on at the paper, while I was thanked for my time and moved along. We had been having drinks with David at the pub near her flat when she announced it, before brushing it off as if it were no big deal.

I managed to hold it together just long enough to hug her before slipping away to the bathroom and weeping hot, angry tears into my sleeve. It would have been impossible for the two of them not to notice the red stains around my eyes when I emerged five minutes later, claiming to have had an allergic reaction to my make-up.

By the time I reached the Tube platform, later that evening, I was numb, unable to feel the tears dropping from my eyes. Would Meg have asked me to move in if she had not been feeling guilty about the job? I would question it later, just as I would question everything else. Back then, though, I was in no doubt – she was as committed to me as I was to her.

When David rang the day after Meg’s announcement about her new job on the news desk, I ignored his call before turning my phone to silent. It was a Saturday and the only noise from the street outside my parents’ house came from the neighbours herding their children, laughing, into the back of a black hearse-like car. Aside from the occasional movement on the stairs, inside the house stung with silence.

When he rang again, an hour or so later, his name flashing on the screen like a hand reaching in from another world, I pressed decline, too bereft to speak, and just like that he was gone. I was halfway to the bakery, to ask for my old job back, when I heard a ping alerting me to a new message.

Pulling out the phone, annoyed that he wouldn’t leave me alone with my misery, I read his words and stopped in my tracks.

‘She’s an old family friend.’ His voice rose above the swish of traffic when I called back a few minutes later, moving slowly along the grey paving slabs of Guildford town centre. ‘I hadn’t seen her in years but she is married to one of the bosses at my firm and we bumped into one another. I told her you had done a degree in English and about your internship at the paper, and … She wants to meet you.’

David’s voice was soft, listening intently at the end of the phone for my reply.

The interview had been arranged for the following week. Clarissa, I discovered, was exactly the kind of woman one would imagine to run a high-end magazine, exuding money and confidence and an overpowering smell of petunia. But she was kind, too, and generous. ‘Any friend of David’s …’ she had beamed, radiating warmth.

The memory of her words sends a pang of sadness through me. Picking up a magazine at random, I use the self-service checkout before making my way to the boarding gate.

I find my seat in Business Class, store my neat black suitcase overhead, and wait for the comforting purr of the engine. As the rest of the passengers fiddle with their seats, I draw out the phone from my bag and compose a message to Harry.

On my way.

‘Cabin crew, prepare for take-off.’

I raise my drink to my lips, the clatter of the ice vibrating against my glass. Gratefully, I absorb the captain’s words, their familiarity grounding me in my seat, creating a rhythm against which my breath rises and falls, in desperate chunks.

They are the same words I have heard on countless flights with David and the girls over the years. Maldives. Bali. The South of France. Of all the places we have been together, it is Provence that I think of now. Maria steadily marching the girls up and down the plane, her monotonous hush-hush enveloping me in a blanket of calm.

I close my eyes but the memory follows me. The girls’ faces trailing the cloudless sky through the car window during the drive from the airport to yet another of David’s father’s houses. This one is cushioned by lavender fields, the smell clinging to the air. The gravel crunched underfoot as we made our way from the cool air of the Mercedes towards the chateau, through a web of heat. My father-in-law was waiting under the arch of the doorway.

I watched him, my skin prickling as he swaggered out to meet us, the underarms of his crisp white shirt drenched in sweat. ‘My dear Anna!’

‘Clive.’ Had his name stumbled on my lips?

The panama tipped forward on his head, jarring against my cheek as he leaned in to kiss me.

‘Two times, darling, we like to play native around here …’ His voice was booming. ‘And where are my girls? Oh, let me have a good look at them.’

Clive blew an ostentatious kiss to Maria, and I worked hard to repress my jealousy at the thread that ran between them, the years their families had been connected in a way that would somehow always trump what David and I had. Maria, carrying one of my girls in the car seat, moving so comfortably alongside my husband, our other daughter asleep in his arms.

Clive took his son by the wrist, and as if reading my need for inclusion, said, ‘Well, I’m glad to see they still have their mother’s looks …’

Steadily, I let myself picture my daughters. Stella, all cheekbones and arch features, strident from the inside out. Her fall to earth padded by the arrival of her sister, a minute earlier.

Stella would be fine. Stella was always fine, always the one to take the best from a situation, and make it hers. But Rose. My eyes prickled.

There was something about Rose that demanded you take care of her, from that first day at the hospital. Even when it was Stella who had needed me. Even though it was Stella who had been the one to give everyone the fright, it was Rose whose cries, when they came, small and unsure, unnerved me. Everything about her was milder, from the delicate features to the way she hung back, always letting her sister wade in ahead, gung-ho. The truth is, I see more than just my own face in Rose, and that is what scares me most.