Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Ching’s Fast Food: 110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites»

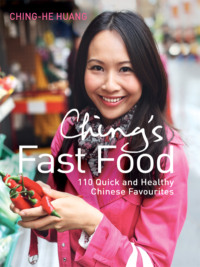

Ching’s Fast Food

110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites

Ching-He Huang

For all my family, friends, fans and ‘gue-ren’, thank you so much from my heart. A little bit more of me to you, with love.

Contents

Introduction

Breakfast

Soups

Appetisers

Chicken & Duck

Beef, Pork & Lamb

Fish & Shellfish

Vegetarian

Specials

Rice

Noodles

Dessert

Equipment

Glossary

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Enough is enough.

Chinese food doesn’t get the recognition it rightly deserves in the Western world. French, Japanese, even Korean cuisine all receive high praise from food critics in the press, but Chinese food remains underappreciated. Chinese cuisine can be just as complex or as basic as any other cuisine. It has so much to offer and has given so much already. It has travelled all over the world with immigrant Chinese families and its influence can be seen in the food cultures of many different countries, from Asia – Japan, Thailand and Vietnam – to Indonesia and the West.

Did you know that there are more takeaway Chinese restaurants in America than every McDonald’s, Burger King and KFC put together? In the UK there are more than 15,000 Chinese takeaways and restaurants, and Chinese takeaways have officially overtaken Indian takeaways as the nation’s favourite type of meal to order in every week. In America, Chinese restaurants first developed to provide food for the railway workers in the 19th century. Immigrant chefs had to use local ingredients to cater for their customers’ tastes, so dishes were given a name and number and served with a very un-Chinese roll and butter. These were the circumstances in which Chinese takeaway menus were first devised.

During this period and over the years, many inventive takeaway dishes were created, including egg foo yung (omelette served with gravy), chow mein (stir-fried noodles), chop suey (leftovers in a brown sauce), crispy beef and General Tso’s chicken (battered chicken in a spicy sweet ketchup sauce) – dishes as well loved in Britain and America as shepherd’s pie, or steak and chips.

If you are a fan of your local Chinese takeaway and you then travel to China, my guess is that you will experience more than a culture shock, for the food will seem very unfamiliar. Some English businessmen have admitted to me that they fill their suitcases with crisps and other goodies when they travel to China because they cannot stomach the food there! If you go with an open mind, however, you’ll discover a whole new culinary world. Should you be lucky enough to dine with Chinese friends at their favourite Chinese haunt, you’ll find the menu will be dismissed, there will be a few exchanges of Cantonese or Mandarin, some quick scribbles by the waiter and you’ll be treated to such delicacies as clay pot chicken, braised chicken’s feet, ‘fish-fragrant’ aubergine, steamed sea cucumbers and baked salted chicken.

But there are signs that the disparity between takeaway food and ‘real’ Chinese cuisine is lessening. China has opened up over the last decade and there are now many more opportunities for travel to and from the country. The internet has helped too. As a result, more people are beginning to appreciate that Chinese cooking is much more than what is served at their local takeaway.

Chinese takeaway food has also recently moved on and become more exciting. There are more dim sum restaurants than ever, for instance, and while Cantonese cuisine is still the most widely served outside China, establishments offering dishes from other regions are sprouting up all over the place – no longer just Cantonese, but Sichuanese, Hunanese, Taiwanese and Shanghainese. Chinese takeaway food remains a huge phenomenon. Chinese takeaways can be found all over the world and each one has a unique story attached to it. Often you will hear how someone’s grandfather started the takeaway, or how the place has been in the same family for generations. By contrast, others have changed ownership many times, serving as a golden goose for perhaps a decade before being passed on.

When my family first arrived in England and we stood waiting for a train, I remember an elderly couple asking my father whether we owned a takeaway or Chinese restaurant. That was two decades ago when it was the norm for newly arrived Chinese families to open a takeaway. The majority of my father’s friends in the Chinese community in London owned takeaways.

In hindsight, my father thought he probably would have been more successful had he followed suit rather than going into the import–export business. At the time, however, he felt this was the right thing to do, as my grandparents were proud that their eldest son had graduated with a business degree and were prejudiced against him working in catering, which was considered laborious and low skilled (still the view in China today).

My first takeaway experience was in England – at a small place on the Fortune Green Road in North London. Prior to that I had never had food from one. My mother is a great cook, and when we lived in South Africa (before travelling to England), she made all the meals. Her recipes were mainly Chinese but with a South African twist, such as a stir-fried or traditional stewed dish served with miele pap (rather like polenta) instead of boiled rice.

In fact, there were no Chinese takeaways that I can recall during my time in South Africa. There was only one Chinese supermarket in Jo’burg at the time, which my mum would religiously frequent every week to stock up on provisions for her Chinese larder.

In England, by contrast, there were a lot more takeaways and one busy weekday, shortly after we had arrived in the country, we ordered from our local. The experience wasn’t too bad, but Mum found it overly expensive and the fried rice not up to standard, so she turned her nose up at it and we never ordered from there again. The takeaway remains in business, however: last time I passed, it was still there. Mum preferred the Cantonese restaurant, the Water Margin, on Golders Green Road, and we went there when she wasn’t in the mood for cooking. The restaurant became the place where I could meet my friends (or a date) for a quick Saturday lunch while satisfying my craving for Cantonese roast duck on rice.

Chinese takeaways are the ‘fast food’ of Chinese cuisine. A takeaway is where you would go to get your fried spring rolls, fried wontons, special fried rice or beef with greens. It is usually a lot more salty and oily than home-cooked Chinese food, in which dishes are a lot simpler, less rich and better balanced. It is no wonder that Chinese takeaways have created a bad name for themselves with many using high levels of monosodium glutamate to enhance the flavour. Although MSG is a natural substance, found in many foodstuffs, used as an additive it can have adverse effects. I personally have an intolerance to it, suffering from heart palpitations and a dry throat.

To me, if you use the freshest ingredients, you don’t need MSG because the dish will be full of flavour, especially if those ingredients are in season and at their very best. Many manufacturers of Chinese or Asian condiments often add MSG, and I have found that a small amount within a sauce is fine, but commercial sauces can contain quite a bit. Try and find ones that don’t have MSG and contain ingredients that are as natural as possible. Best of all, create your own sauces – in this book I’ll show you how to use store-cupboard ingredients to make your own. It is true of all cuisines that the foods you cook yourself at home will be healthier and lighter than any takeaway food. In fact, a recent report showed that a meal cooked at home contains on average 1,000 fewer calories than its takeaway/restaurant equivalent and considerably less salt. Even though my grandmother was partial to a little ‘gourmet powder’ (MSG) from time to time, she always practised what she preached – to be certain of what you’re eating, it is better to cook the food yourself.

That’s not to say that I’m not partial to a Chinese takeaway myself; indeed, there is a good one near where I live in North West London. I happen to know the owner and have been to the factory where the special 11-spice powder they use for their crispy aromatic duck is lovingly ground, and it’s so good! When I don’t have anything in my fridge or want to give myself time off in the kitchen, I just give them a ring and order number 15. But unless you know the establishment well, it’s like takeaway roulette, and we’ve all had a bad takeaway experience at some time or another. If you have a reliable local takeaway, support the owners and treat them like family!

I actually love Chinese food in all its forms – Americanised, anglicised, even bastardised. I recently had the pleasure of trying Chinese chicken salad American-style and I could see the attraction in the sweet orange sauce coupled with crispy fried wonton skins, crunchy lettuce and chicken strips. Yes, God forbid, I have even had a craving for it since! (I blame it entirely on the sugary sauce.) There is beauty in Chinese takeaway food that is cooked well – even a pretty standard dish like sweet and sour pork balls. I know some expats living Hong Kong who demand to have some of the anglicised takeaway stuff and would import it if they could. It is simply a matter of taste. And what most fascinates me is how thousands of people all over the world are united in their love of Chinese takeaway food, while the forefathers of this invention were completely unaware that they were the pioneers of Chinese fast food and the very best in their field. It is an amazing achievement when you think about it: these days R&D (research and development) chefs get paid six-figure sums to come up with what they did.

In my quest to share my love and appreciation of Chinese food, I myself have been blamed for ‘dumbing down’ Chinese cuisine for the Western palate in my attempt to whet people’s appetite for it. But I much prefer to see it as ‘creative fusion’. If I remained true to the Chinese classics, I would be a copycat cook and not a progressive one. A cook’s job in my opinion is to be creative and push the boundaries of their cuisine and never stop experimenting.

Yes, classics are good, but classics at one point in history came from somewhere too. They were once new – someone invented them, and if they had never experimented, we wouldn’t be enjoying those dishes today.

And are classic dishes the only authentic ones? I prefer the term ‘heritage’. Dishes can have heritage and influence, but they are not necessarily ‘authentic’ because the question would be, authentic to whom? Authenticity is a matter of perspective. Chinese takeaways have become such a staple of so many different countries that you could argue that they are just as authentic within immigrant Chinese cooking as the older, classic dishes.

I am always being asked for takeaway menu recipes, so here is my book on the subject. Don’t accuse me of not knowing my xiao long bao from my char siu bao – because I do and I can make both. I want to share my love of Chinese takeaways and show how, cooked well, they can hold their own with the other great cuisines of the world. People also ask me whether I cook other types of food at home, and I certainly do. In fact, I have a soft spot for Lebanese cuisine, and I love Italian and Indian. But my vocation and career is making Chinese food – and please excuse the generic word ‘Chinese’, for there are over 34 regions in China with over 54 different dialects and each region has a unique way of preparing food. So until I master all the Chinese dishes there are to be mastered and explored, I won’t be able to venture properly into other cuisines. Chinese cooking alone could keep me going for more than a lifetime.

If you are Chinese and, like my father, snobbish about Chinese takeaways, my hope is that, after reading these recipes, you will be cooking and feeding them to your kids instead of the dog and you will feel encouraged to embrace them as part of your culture and be proud of them.

Chinese takeaway cuisine is perfectly acceptable at home too, and I want to prove that, when cooked correctly, it can be the healthiest, most economical and delicious food you have ever eaten. With many low-fat dishes and using plenty of fresh vegetables and lean meat and fish, it’s also good for those who are worried about keeping slim. If you are vegetarian, Chinese food has a huge array of bean curd and ‘mock meat’ recipes made from wheat gluten. Equally, if you are allergic to wheat or gluten or to monosodium glutamate, you can buy soy sauces that are wheat-free and condiments that don’t contain MSG. If you have a nut allergy, use vegetable or sunflower oil instead of groundnut oil, and if you are watching your salt intake you can substitute a low sodium, light soy sauce. I would also advise using organic or free-range eggs and meat wherever possible.

With this book, I want to give you my 21st-century version of the Chinese takeaway, inspired by this favourite fast food. I want to demonstrate how I think Chinese takeaway dishes should be cooked at home. I will look at all the offerings, whether healthy or unhealthy, give my view on them, share tips with you and show you lots of easy recipes that can be cooked far more quickly than it would take you to order your favourite takeaway dish. I will share with you my knowledge of flavour pairings to get the best out of your Chinese store cupboard (see the box above for my top ten ingredients) and introduce some new ways of eating and cooking Chinese food. In addition, I want to show you how Chinese takeaway dishes, when cooked with the freshest ingredients you can lay your hands on (coupled with the right culinary techniques), is a far superior ‘fast food’ than any other cuisine in the world. If I owned a takeaway, the dishes in this book are the ones you’d find on my menu.

Enough said. Less talk and more cooking!

MY TOP TEN ESSENTIAL CHINESE STORE-CUPBOARD INGREDIENTS:

1. Light soy sauce

2. Dark soy sauce

3. Shaohsing rice wine

4. Toasted sesame oil

5. Five-spice powder

6. Sichuan peppercorns

7. Chinkiang black rice vinegar

8. Clear rice vinegar

9. Chilli bean sauce

10. Chilli sauce

Breakfast

When I first arrived in South Africa, I was five and a half. After a tearful goodbye to the rest of the family, my mother, brother and I packed our bags to join my father, who had already left to set up a bicycle business in South Africa. In Taiwan he had been working as a manager in a building company and hated his job. So when by chance he met Robert (‘Uncle Robert’ to us) and the South African convinced my father to set up in business with him, he jumped at the idea. We liked Uncle Robert: we had met him only once, but he had taken us to a pizza restaurant and given me a cuddly racoon toy from South Africa. Despite no previous business experience and not knowing a word of English, my father moved us all over there on a whim. It was to be one of the scariest but most fulfilling adventures of my childhood.

At Uncle Robert’s insistence, we stayed on his farm just outside Jo’burg. He and his wife Susan accommodated us in a converted barn on their plot of land, which extended for acres and acres. They even had a mini reservoir with their own supply of water and they kept horses and several Rhodesian Ridgebacks. Aunty Susan was a welcoming lady. The day we arrived, while my mother was unpacking and tidying up the barn, she took us food shopping. My brother and I were taken to the most enormous building we had ever seen. It was a hypermarket. Back in Taiwan, I hadn’t even been to a supermarket before. Even in Taipei, the only modern outlets we had were 7-Eleven convenience stores. The only place like it in our experience was the local wet market my grandmother used to take us to in the village, so this vast building was a shock.

My brother and I went up and down the aisles, admiring the rows and rows of packaged ingredients. There were even fish tanks with fresh lobsters and crabs. Aunty Susan guided us to a large chilled section; I remember feeling really cold. She pointed to the shelves and gestured to us to pick something, so I picked a small light brown carton and my brother picked a dark brown one. We hadn’t a clue what we had chosen. The rest of that shopping trip is now hazy, although I remember plenty of boxes and paper bags being carted to Aunty Susan’s large fancy kitchen.

She handed us each a teaspoon and we left her to her unpacking. I opened the foil lid of my carton and took a small mouthful, and my brother did the same. The taste was creamy and sour but also sweet; I had no idea that I had picked a caramel-flavoured yoghurt and my brother a chocolate one. We were used to our Yakult, but this was an entirely new experience. We weren’t sure we liked it, but we went back to the barn and showed the yoghurts to Mum. She took a small mouthful and then spat it out: ‘Pai kee yah!’ (‘It’s gone off!’ in Taiwanese). She stormed over to Aunty Susan’s and started ‘communicating’ with her. They couldn’t understand what each other were saying; in the end my mum threw the pots in the bin! Aunty Susan looked bewildered and shrugged her shoulders. I thought Mum was rude, but I didn’t dare say anything. The next day Aunty Susan dropped by as Mum was making us fried eggs for breakfast. She brought over these dark green, what my mum called hulu- or gourd-shaped vegetables. Aunty Susan sliced one in half to reveal a large round stone in the middle; she then scooped the green flesh out of one of the halves and smeared it on to a slice of brown bread she had brought over with her. She gestured to my mother to take a bite. My mum had a taste and shook her head, saying, ‘Bu hao chi’ (‘Not good eat’). ‘Avocaaaa-do,’ said Aunty Susan, then smiled, patted us on our heads and walked out the door.

Despite not liking the taste, my mother hated wasting food, so she placed the eggs she had been frying on the avocado bread, drizzled over some soy sauce and told us to eat it. She didn’t have any herself. Over time, however, avocados became one of my Mum’s favourite foods. She now lives permanently in Taiwan, where avocados are hard to get and expensive. When we Skype, she will often ask, ‘You still eating avocados?’ That recipe, washed down with a glass of soya milk, is now one of my favourite dishes for breakfast.

You will notice that my recipes, like yin and yang, tend to be very black and white, very Western or very Chinese, but when recipes work together, East and West can be balanced, like the takeaway menu, to give amazing, what I like to call ‘fu-sian’-style food. You may not associate breakfast with Chinese takeaways, but there are many eateries all over Asia that serve warming breakfasts, which can be bought on the way to school or work. In addition to Western-style sandwiches, these small eateries (and sometimes street stalls) serve you-tiao, or fried bread sticks, with hot or cold soya milk (sweetened or unsweetened), mantou (steamed buns) with savoury or sweet fillings and of course steaming bowls of congee in a variety of flavours. If I had a takeaway or diner, I would definitely include a breakfast menu, and I would serve a variety of Western and Chinese-style treats – just like the snack stalls in the East.

Toast with avocado, fried eggs and soy sauce

Aunty Susan, whom we stayed with when we first arrived in South Africa, gave my mother two ripe avocados, smearing one of them on some bread. Mum thought it was odd to serve a vegetable in this way, but soon she started to make us fried-egg sandwiches for breakfast with a generous slathering of avocado. Now I don’t hesitate to make this for breakfast, spreading slices of toast with a chunky rich layer of ripe avocado, topped with poached or fried eggs (preferably sunny side up) and a drizzle of light soy sauce. If I had my own takeaway or diner, this would certainly feature on the menu!

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

PREP TIME: 5 minutes  COOK IN: 3 minutes

COOK IN: 3 minutes  SERVES: 1

SERVES: 1

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

2 large eggs

2 slices of seeded rye bread

½ ripe avocado (save the rest for a salad later), stone removed and flesh scooped out

Drizzle of light soy sauce

Salt and ground black pepper

1. Heat a wok over a medium heat until it starts to smoke and then add the groundnut oil. Crack the eggs into the wok and cook for 2 minutes or to your liking. (I like mine crispy underneath and still a bit runny on top.) Meanwhile, place the bread in the toaster and toast for 1 minute.

2. To serve, place the toast on a plate and spread with the avocado flesh. Place the eggs on top and drizzle over the soy sauce, then season with salt and ground black pepper and eat immediately. This is delicious served with a glass of cold soya milk, a cup of rooibos tea with a slice of lemon or some freshly pressed apple or orange juice.

Basil omelette with spicy sweet chilli sauce

In Taiwan, there are many night market stalls that sell the famous oyster omelette. A little cornflour paste is stirred into beaten eggs, then small oysters are added and sometimes herbs. When the eggs have almost set, a spicy sweet chilli sauce is drizzled over the top, making a comforting, moreish snack. I adore this dish, but it is hard to get fresh small oysters, so I make a vegetarian version sometimes for breakfast, using sweet basil, free-range eggs and adding my own spicy sweet chilli sauce, made using condiments from my Chinese store cupboard.

PREP TIME: 3 minutes

PREP TIME: 3 minutes  COOK IN: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes  SERVES: 1

SERVES: 1

3 eggs

Large handful of Thai or Italian sweet basil leaves

Pinch of salt

Pinch of ground white pepper

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

Handful of mixed salad leaves, to garnish

FOR THE SAUCE

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

1 tsp of vegetarian oyster sauce

1 tbsp of mirin

1 tsp of tomato ketchup

1 tsp of Guilin chilli sauce, or other good chilli sauce

1. Make the spicy sweet chilli sauce by whisking all the ingredients together in a bowl, then set aside.

2. Crack the eggs into a bowl, beat lightly and add the basil leaves, then season with the salt and ground white pepper.

3. Heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke and then add the groundnut oil. Pour in the egg and herb mixture, swirling the egg around the pan. Let the egg settle and then, using a wooden spatula, loosen the base of the omelette so that it doesn’t stick to the wok. Keep swirling any runny egg around the side of the wok so that it cooks. Flip the omelette over if you can without breaking it, then fold and transfer to a serving plate, drizzle over some of the spicy sweet chilli sauce and serve with a garnish of mixed leaves.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.