Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

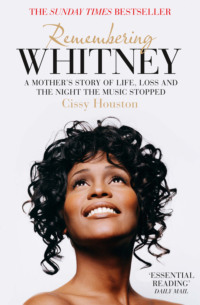

Kitabı oku: «Remembering Whitney: A Mother’s Story of Love, Loss and the Night the Music Died»

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Part One

CHAPTER 1 The Night the Music Stopped

CHAPTER 2 A Child of Newark

CHAPTER 3 The Gospel Truth

CHAPTER 4 Sweet Inspirations

CHAPTER 5 Life on Dodd Street

CHAPTER 6 Training the Voice

CHAPTER 7 Separation

Part Two

CHAPTER 8 Enter Clive Davis

CHAPTER 9 Fame

CHAPTER 10 Welcome Home Heroes

CHAPTER 11 The Bodyguard … and Bobby Brown

CHAPTER 12 “I Never Asked for this Madness”

CHAPTER 13 “I Know Him So Well”

CHAPTER 14 A Very Bad Year

Part Three

CHAPTER 15 Atlanta

CHAPTER 16 The Intervention

CHAPTER 17 The Comeback

CHAPTER 18 “I Look to You”

CHAPTER 19 Bringing My Daughter Home

Epilogue

Picture Section

Acknowledgments

Selected Cissy Houston Discography

Selected Whitney Houston Discography

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

This book is dedicated to my immediate family, particularly my sons and my grandchildren, and to all the world of wonderful fans who loved my daughter. Hopefully you may get to know Whitney through the love I’ve shown in these pages.

“I’ll lend you for a little time a child of mine,” He said.

“For you to love while she lives and mourn for when she’s dead.…”

—adapted from “I’ll Lend You a Child”

by Edgar Guest

Foreword by Dionne Warwick

I’ve known Cissy Houston my whole life. She’s my aunt—her sister Lee is my mother—but because we’re only seven years apart, she felt more like an older sister to me.

When I was growing up, Cissy even lived with us for a while in East Orange, so I got to know her pretty well. I can still hear her voice, telling my sister Dee Dee and me, “I am older, and you are going to do as I say.” She might have felt like an older sister to us, but she never let us forget she was our aunt. She was a strong young woman then, and she is a strong, loving woman now.

From the time we were children, we all sang together at St. Luke’s A.M.E. Church in Newark, where my grandfather was the minister. Later, when he moved away, we all joined New Hope Baptist Church. My sister Dee Dee and I sang in the junior choir there, and Cissy rehearsed us and arranged songs for us. Music was always in our family’s blood. But there were two things even more important to us than music: family and faith.

When she started having children, Cissy became very mother-oriented. Her kids were primary in her life—she had to be with her babies. There was a great deal of love in their house. And we all loved her children, Gary, Michael, and Nippy.

When Cissy’s kids were small, I used to like to bring them out on the road with me. By that time, I had a solo career and was touring all over the world, so during the summers, when they weren’t in school, I’d bring them out to join me. They were just regular little kids on summer vacation, but they did learn how to use room service very, very quickly. It was all I could do to keep those children from ordering everything in the world up to the room.

Nippy used to talk with me about her mother, just the usual kids’ stuff of “Why won’t she let me do this?” and “How come the other kids get to do that?” But later on, she came to realize why her mother did the things she did. We all were brought up in the same way—it was instilled in us to respect our elders, to love God, and to walk the straight and narrow. And that’s what Cissy tried to teach her own children, too.

Cissy has always wanted the best for everyone in her family. She’s always giving encouragement and support, and she’s tried on many occasions to give advice. Whenever she saw something that wasn’t sitting too well with her, she’d speak up. As I did. In our family, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

But while Cissy was strong and loving, Nippy was always a little girl, even during her womanhood. Yes, she was ambitious, and she had a silent strength. But I’m not sure it was ever really tapped into. We all know of Nippy’s beauty and her amazing vocal skills. But in Cissy’s book, you will learn about the little girl behind all that.

It’s a privilege to have a peek inside someone’s life, and that’s what Cissy is offering in this book. The truth has always been paramount for Cissy, and I believe she has given the truth within these pages. The fact that she found the strength to write it now, given the grief she has suffered, is a testament to her faith: she is being led to share her true feelings about herself and her beloved daughter.

I hope all of us can take a lesson or two from it, and that with this book, everyone can read about and understand who Whitney Houston truly was.

Dionne Warwick

November 2012

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

The Night the Music Stopped

It was the middle of the afternoon on a Saturday when I heard my doorbell ring.

I wasn’t expecting anyone, and walking to the door I felt a little irritated about a surprise visit. But when I opened it, no one was there, so I just shut the door and went back to whatever I was doing. Who would be ringing my bell and disappearing in the middle of the day? My apartment building had a doorman, and it wasn’t like people were just dropping by all the time.

Not long after, I heard that bell ring again. I got up and went to answer it, really irritated now. But again, no one was there. Now, this just didn’t make sense. Why would someone be messing with me like this? I called down to the front desk.

“Has anyone come up to see me?” I asked the concierge.

“No, Mrs. Houston,” he said. “I haven’t seen anyone on the cameras, either.” Well then, who was ringing my bell?

Not long after that, around six or six-thirty in the evening, my phone rang. When I picked it up, all I could hear was screaming.

“Oh, Mommy! It’s Nippy! It’s Nippy!” It was my son Gary on the line, and he was hysterical.

“Gary, what’s wrong?”

“It’s Nippy,” he said again. “They found her!”

“Found her where?”

“They found her upstairs,” he cried. “They found her upstairs and I’m not going back up there!”

“Gary, what happened?” I snapped, frightened now. “You’ve got to tell me what’s wrong!”

He never did say what had happened, maybe because he didn’t know exactly, or maybe because he was in shock. He just kept mumbling, “Oh, Mommy, Mommy, Mommy,” until I finally said, “Gary, is she dead?”

And he said, “Yes, Mommy. She’s dead.”

And that was the moment my whole world shattered.

I don’t know what I did or said after that. I was told later that I screamed so loudly that the whole building must have heard me, but my mind was absolutely blank, except for one thought: My baby was gone.

Somehow, people started showing up at my apartment. My niece Diane came, and other friends and family. The phone rang, the doorbell chimed, people brought food, people tried to hug me. But I just sat in my chair, crying. I was in shock, and even now, I really don’t know how I survived that evening—or the days that followed.

As soon as the news got out, all sorts of people surrounded my apartment building. Reporters lined the lobby trying to get in to ask questions, and strangers snuck up to my floor wanting to pay their condolences. The crowds got so thick outside the building that the police had to be called to keep people away. But I didn’t know any of that at the time, because all I could do was weep and moan and wail. All I wanted was to be left alone to grieve for my daughter.

The last time I’d seen Nippy, I had been a little upset with her. It was around the Christmas holidays, just six weeks or so earlier, and she’d suddenly showed up in New York with my granddaughter, Krissi. Nippy wanted me to come into the city and join them, and my sons Gary and Michael, but she hadn’t told me they were coming, so I’d made other plans. I was going up to Sparta, New Jersey, to have Christmas dinner with my friend Nell, and I didn’t feel right breaking it off, since we’d been planning it for a long time. I wanted to see Nippy, of course, but I just wished she would give me a little more notice when she was coming through.

So I went up to Sparta and spent the night there, and then the next day Nippy called me again, asking me to please come into New York and see them. She was staying at the New York Palace hotel, and Gary and Michael and their wives and children were all there, so it looked to be a nice family reunion. I went into Manhattan, excited to see the whole family together, which was a real rarity these days.

Nippy had just finished working on her new movie, Sparkle, and she looked fantastic. The whole day she was in good spirits—laughing and joking with her brothers, and playing with the kids. She’d always had a good relationship with her brothers, and as I watched them laughing together it felt like old times. We had all been through a lot in recent years, but this day it felt like we didn’t have a care in the world.

At one point in the day, as I was sitting on the sofa, Nippy leaned over and put her head in my lap. This was something she didn’t do all that often, but I always loved it when she did. She and I were very different people, and like any mother and daughter, we’d had our difficult moments over the years. But when Nippy would put her head in my lap, those were the moments that bonded us together, and I cherished them.

I knew Nippy was returning to Atlanta the next day, and I hated that our visit was so short. I was always asking her to come up and visit, as I hadn’t gotten to see very much of her in recent years. But now that she seemed to be in a better place, with her new movie and a new lightness about her, I hoped that would change. As I got ready to leave, Nippy and I stood talking at the door.

“I’ll come back soon, Mommy,” she said. “I’ve got to go to L.A. for the Grammys in February, but I’ll come see you after that.”

My daughter had come a long way from being a skinny little girl with a big voice growing up in Newark, New Jersey. She had traveled the world and become a sophisticated, powerful woman—but there was something in our relationship that always brought out the child in her. When I looked at Nippy, I saw the little girl who used to grab a broom and belt out songs in our basement studio like she was onstage at Carnegie Hall. And I saw the uncertain girl who wanted everyone to like her, who just wanted to sing to make people happy—not to sell millions of records or be a global superstar.

But she did become a superstar, and the pressures that brought eventually overwhelmed her. She endured so much, and was criticized so mercilessly by people who didn’t understand her—people who didn’t know who she was. She always used to say to me, “Mommy, I just want to sing.” Yet that would never be enough.

For everything Nippy went through, with drugs, with her relationships, with the pitfalls of fame, she really did seem to be on an upswing in the weeks before she died. During those weeks, whenever we spoke on the phone, she sounded so good, like she was feeling better than she had in years.

When she called me in early February, though, just before she left for Los Angeles and the Grammy Awards, she didn’t sound like herself. There was a sadness in her voice. Nippy never liked to share her problems with me—she was just private that way – so I didn’t know exactly what was wrong. We all have our ups and downs, so I didn’t worry too much about it. I knew she’d be busy in Los Angeles, with the awards and all the other events that went on, and I didn’t really expect to hear from her again while she was there.

But on the Friday before the awards, she did call me. She sounded a little better, though she still didn’t share much of what was going on. I don’t remember most of what we talked about, but I do remember the last thing she said to me on the phone. Back in December, she had promised to come see me after the Grammys, and before she hung up on that Friday, she said it again. “I’ll be home soon, Mommy,” she told me. “I promise.”

Those were the last words I would ever hear her speak.

The next day, Nippy died. And the days that followed were a seemingly endless blur of grief and pain. There were times when I didn’t think I could live through the despair of losing my baby girl. I just couldn’t believe I would never see her, or hear her voice, in this world again. I still can’t believe it.

But I did take solace in one thing. On that terrible day, when my doorbell kept ringing in those hours before Gary’s call, I believe it was my beautiful Nippy, keeping her promise to me—that somehow, some way, she came to see me, just as she said she would.

CHAPTER 2

A Child of Newark

It was a hot August night in 1963 when Nippy was born. I was doing session work as a background singer, and despite being overdue and big as all get-out, I’d worked a full day. My husband, John, picked me up at the studio in Manhattan and drove me home to our apartment in Newark, New Jersey, but not long after we walked in the front door, my water broke. So it was right back out the door as John put me in the car and hurried to Presbyterian Hospital.

From the moment I found out I was pregnant, I had hoped this baby would be a girl. I already had two boys, my sons Gary and Michael, and I knew this would be my last child. I was tired of having babies, and I surely didn’t want to go through what my mother had endured—she had eight children by the time she turned thirty. Three was enough for me, but I desperately wanted this last one to be a girl—although personally, I was convinced that I was about to have another big-headed boy. At that time, of course, you couldn’t find out until the baby was born. There were old wives’ tales about being able to tell depending on whether you carried the baby high or low, but nobody really knew.

What I did know was that this baby already seemed to love music. All during my pregnancy, I’d been doing session work—singing backup for artists such as Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, the Isley Brothers, Aretha Franklin, and my niece Dionne Warwick—and the whole time, that baby never stopped moving inside me. Sometimes, it even seemed to be moving to the music. So, one thing I knew for certain—that child was going to have rhythm!

We got to the hospital and checked in, but I don’t remember much after that. This was a big baby, and the delivery wasn’t easy. After hours of pain, the doctors gave me an anesthetic to knock me out, and when I finally woke up, John came into the room and told me we had a baby girl. I don’t know why, but I didn’t believe him. I thought he was just playing a joke on me.

“I’m telling you, Cissy, it’s a girl,” he said, laughing.

“Stop that mess, John! You’re lying.” John always liked to tease and joke, but I wasn’t having any of that right now.

“No, really,” he insisted. “It’s a girl.”

“And she’s gorgeous,” chimed in a nurse who was standing there.

Well, there was one way to find out. “Where is she?” I asked.

It turned out the hospital staff were taking her around to show her off. The nurses were just carrying my little baby all over the hospital floor, showing her to their co-workers and everyone else. It was as if she belonged to the public the very second she was born.

I was so mad—here I was, lying exhausted in a hospital bed, and I couldn’t even see my own child because everyone else had to get a look at her first.

“You better go and get my baby!” I told John.

One of the nurses hustled off, and a few minutes later I finally saw my baby girl for the first time. Someone had already tied a little pink bow in her hair, and she was the most beautiful little thing I’d ever seen. I held her in my arms, and I couldn’t believe it. She was eight pounds and four ounces, and she had everything—a head full of hair, eyelashes, fingernails, everything.

I was so excited, so happy, that I burst into tears of joy. I named her Whitney Elizabeth—Whitney, the name of a TV character I liked, because I thought it was classy and a little different. And Elizabeth, after John’s mother.

I was beyond thrilled that I’d gotten my wish to have a girl, and I wanted Nippy to be a special kind of child. She was my princess, my perfect little jewel, and from the very beginning I wanted to protect her. I didn’t want my sweet baby ever to know hardship, if I could help it, because hardship was something I had learned plenty about in my own childhood.

As sweet as my Nippy was, I always had a harder shell, ever since I was a girl. I didn’t have much choice, considering all the things that happened to my family as I was growing up in Depression-era Newark.

My parents, Nitcholas and Delia Mae Drinkard, came north to Newark from Georgia in 1923. The city of Newark had built wooden tenement houses for working-class black folks and immigrants, and that’s where they settled—on the top floor of a three-story building with a pull-chain toilet all the way down on the back porch. When they arrived, my parents already had three children—a son, William, and two daughters, Lee and Marie—and over the next ten years, they’d have five more: Hank, Anne, Nicky, and Larry, and finally me, in September 1933.

Our apartment, at 199 Court Street, was in the middle of a racially mixed working-class neighborhood. It had its rough edges, but there were also churches on just about every corner. Both of my parents were devout Christians, with deep roots in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, so my siblings and I grew up in the faith.

My mother was a homebody, a soft-spoken woman who rarely left the house except to go to church, where she served as a steward. Only three things mattered to her: God, her husband, and her children. And I never heard her complain, even though it was a constant struggle to keep eight kids neat, clean, and well fed on my father’s Depression-era salary of eighteen dollars a week.

My father did backbreaking work, first doing road repair in Newark, and then pouring iron in the blazing-hot foundry of the Singer sewing machine factory in Elizabeth. His was a hard life, but like my mother he had a strong faith, and he was never afraid to let it show. Daddy wasn’t a singer, but in church he would hum along during the testimonials—a tradition in the black church in those days. My father praised God and prayed all the time, openly, without any hesitation. He once even got right down on his knees on the factory floor, to pray for another worker’s mother.

Tall and light-skinned, with penetrating blue-gray eyes, Daddy was an imposing man with strong beliefs—one look at him and you knew he didn’t take no mess. That was true not only within the church, where he was a trustee and a vocal member of the congregation, but also at home, where he taught us everything we needed to know about Jesus and faith.

And oh, he could be strict. He was determined to protect his children from corruption and temptations, so he kept a close eye on us, requiring us to be home before dark and say our prayers before every meal. Daddy usually led us in prayer, but every so often he’d direct one of us to do it. As my sisters and I came of age, he also demanded that we teach Sunday school—it was his way of making us learn through teaching. He wanted all his children to have strong Christian faith and walk the straight-and-narrow path, just as he had.

But as hard as my father tried to protect us from the world outside the church, he couldn’t fully insulate us from the temptations of the streets. My oldest brother, William, who was fifteen when I was born, fell prey in his teenage years to the allure of Newark’s darker side. He began hanging out in the streets, gambling, drinking, fighting, and doing who knows what else. William had a hot temper and a mean streak, and when Daddy confronted him about straying, he fought back. I was too young to know what was happening, but they clashed hard, and William left home to make his own way. Our family was close-knit, and it was devastating for my mother to see her eldest son walk out the door. At that time, I had no idea how hard it must be for a mother to watch her child stray into danger and temptation. Many years later, I would learn that feeling all too well.

My mother was already under tremendous stress, trying to feed and care for so many children. The pain of William’s departure only added to it, and after he left, her health got worse. She had other burdens to bear, too—in the years after I was born, she lost two sets of twins at birth. Losing four babies in such a short time, and losing her eldest son to the streets, proved too much for her. At age thirty-four, my mother had a stroke.

My mother’s life—and ours—would never be the same after that. The stroke damaged the right side of her brain, she lost the use of her left arm, and her left leg was also impaired. I was just a child, but watching my mother struggle to recover from her stroke taught me what suffering looked like. My sisters and I spent long hours massaging her leg to try to increase circulation and comfort her. Because it was hard for her to move around, she only left the apartment for emergencies and church. Every single Sunday, my father would lift her up, carry her down the three flights of stairs, then push her in her wheelchair to church. And when they came back, he’d carry her back up those three flights. Seeing my parents’ example, I grew up believing that no matter the hardship, you can overcome it with determination.

But there remained many more lessons to be learned, because our family’s troubles had only just begun.

Not long after my mother’s stroke, a flash fire broke out in the paint store on the first floor of our tenement building. The fire spread with a fury, and although we were all able to get out of the house safely, we had no time to save our possessions. We all ran across the street and huddled there, frightened, as the flames rose higher amid the shrieking of sirens and people’s screams.

My father held me in his arms, and as I clutched his neck in terror I watched the flames climb higher, engulfing our home and then consuming the entire block of tenement houses. I looked at my father and saw tears roll from his eyes as he watched years of our family’s memories burn. The fire destroyed not only our home, but just about everything we owned—our clothes, our books, family photographs, and what few playthings we had. And because our extended family—Daddy’s parents, Mommy’s sister and mother, and several aunts and uncles—had lived in that same block of tenements, their places burned, too. We’d all have to move.

The fire scattered the Drinkards all over Newark, but strangely, in other ways, it was a godsend. If it hadn’t been for that fire, it would have taken us years to save enough money to move out of the tenement. But afterward, with the help of city services, we were able to move into an apartment in a much better neighborhood. From the ashes of something terrible, something good was able to emerge—another lesson that imprinted itself on my young mind.

Once we settled into our new neighborhood, our family started attending St. Luke’s A.M.E. Church. At age five, I was too young to understand much of what was going on, but I was drawn to the joy and enthusiasm that seemed to swell up in that place. You could feel the force of the Spirit and the music the minute you stepped inside those doors.

St. Luke’s was more than just the place our family went to Sunday school. It was the place where my brothers and sisters and I learned to sing.

At first, I wasn’t all that interested in singing. But the music at St. Luke’s was different. At St. Luke’s A.M.E., they not only had a piano, they also had cymbals, tambourines, and even a washboard. This was where we learned to clap our hands in time, and where we learned syncopation, the offbeat rhythm that’s a cornerstone of so many musical styles. It’s where we learned to play the tambourine, and to harmonize. And it’s where I first began to experience music as something spiritual.

Inspired by the music in that church, my brothers and sisters and I started singing together. I don’t remember when we first started, but the minute we did, something just clicked—we could hardly believe what was coming out of our own mouths. We were blessed with some truly great singers in my family (all except poor Hank, who couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket), and when my father heard us sing together, that was it—our carefree childhood days were over.

Daddy made us practice together every single day. I didn’t want to, of course—I just wanted to keep playing like all the other five-year-old kids. Sometimes I’d hide in my room, or I’d run outside and duck behind the car, and my father would threaten me with a beating to get me to come join the others. He never did actually spank me, because, as the youngest, I was his “baby.” But he surely did spank my brothers and sisters—Daddy was not one to fool around if he wanted something done.

My sister Marie, who we called Reebie, taught us songs and rehearsed us, and she was just as strict as my father. We’d learn the melody of a song from the hymnbook, then add in the harmonies, and then finally improvise. “Strike me up a tune!” my father would say, and we’d stand in a group, hold up a broom like a microphone, and start singing.

I could see the pride in my father’s eyes when we sang, but you know, he wasn’t training us to make himself proud. As we started performing in churches, and later in concert halls, he really saw us as junior missionaries—young ambassadors of God’s Word. He wanted us to be a positive influence on other young people, and to carry God’s Word and the family name with our own group: the Drinkard Quartet.

For a time, things were good. We might not have had much money, but we had enough—and more important, we had each other, our faith, and our music. But just as life seemed to be getting better, my mother had another stroke.

From that point on, my mother’s hospital visits became part of our family’s daily life. Every so often, sometimes in the middle of the night, she’d go to the hospital and stay there for a few days. After a while, we kids would hear from a relative or neighbor that she was coming home, and we’d crowd into the front window of our apartment to watch for her and my father coming up the street, him pushing her in her wheelchair.

We were always so happy to have Mommy home, but after those hospital visits she usually needed relief from taking care of the three youngest children—Larry, Nicky, and me. So, during these times, Larry and Nicky were sent to stay with relatives who still lived near Court Street, and I got shipped off to Newark’s Ironbound section to stay with my aunt Juanita. I hated staying with Aunt Juanita, not only because I missed my brothers, but also because she was a mean, nasty woman. She wasn’t like my other relatives—she dipped snuff and was always trying to get a rise out of everybody. Every day I spent at Aunt Juanita’s, I prayed for my mother’s quick recovery.

When Mommy was feeling better, and we could all be at home again—those were the happiest times of my young life. But they lasted only until one terrible night in May 1941, when I was eight years old. That night, my mother began having seizures, and blood started pouring from her mouth and nose. Daddy and my older sisters tried desperately to stem her bleeding and comfort her, but the blood was still gushing out when the ambulance arrived. Mommy was rushed to the hospital as my brothers and I slept through it all, unaware that anything was happening.

The next morning, we were told only that our mother had gone to the hospital. And later that day, when a neighbor boy yelled up to us that he saw Daddy coming up the street, Larry, Nicky, and I gathered in the window of our apartment, just like we always did, to watch for Daddy rolling Mommy up the street in her wheelchair.

That’s when mean Aunt Juanita yelled up to us, “Get out of that window, children! Don’t you know your momma’s dead?”

I didn’t even have time to take in her words before I saw my father walking up the street. His head hung down, and he was leaning heavily on Oscar, my mother’s brother. He was crying, and my mother and her wheelchair were nowhere to be seen. As it turned out, she’d suffered a severe cerebral hemorrhage and hadn’t even made it to the hospital.

My beloved mother, Delia Mae Drinkard, had passed. She was only thirty-nine years old.

I didn’t know how to cope with the terrible feeling of emptiness that settled over me after my mother died. I didn’t think I’d recover from it, and I’m not sure I ever did.

I was only eight, and the very idea of death was hard to put my head around. To make matters worse, no one had the time or inclination to talk to me about it. I think my father, sisters, cousins, aunts, and uncles all assumed I was too young, so I was left to deal with it on my own. In fact, for years afterward, my sisters avoided talking about Mommy’s death, as the mere mention of her name brought tears to their eyes. And so I learned very early on to tamp down my feelings of sadness and just get on with life—because there really wasn’t any other choice in the matter.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.