Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Second Sister»

Copyright

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed

in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Claire Kendal 2017

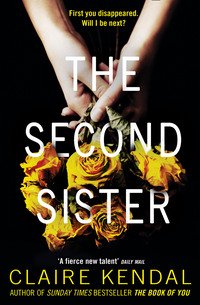

Cover design Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover image © Roberto Pastrovicchio/Arcangel Images

Claire Kendal asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive,

non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled,

reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval

system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or

hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © MAY 2017 ISBN: 9780007531707

Source ISBN: 9780007531714

Version 2019-05-22

Dedication

For my Sister.

And for my Daughters.

She had no rest or peace until she set out secretly, and went forth into the wide world to trace out her brothers and set them free, let it cost what it might.

The Brothers Grimm, ‘The Seven Ravens’

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Late November

Eyes Like Yours

Saturday, 29 October

The Two Sisters

The Costume Party

The Three Suitors

The Fight

Monday, 31 October

The Scented Garden

Trick or Treat

Friday, 4 November

Small Explosions

The Photograph

Saturday, 5 November

Bonfire Night

Pandora’s Box

Monday, 7 November

The Doll’s House

Tuesday, 8 November

The Address Book

Wednesday, 9 November

The Catalyst

Thursday, 10 November

The Woman in the Chair

The Man in the Corridor

The Letters

Friday, 11 November

The Anniversary

Saturday, 12 November

Yellow Roses

Sunday, 13 November

Hide and Seek

Monday, 14 November

Never Climb Down

The Masquerade Ball

Tuesday, 15 November

The Tour

The Door at the End

Jewels

Wednesday, 16 November

The Cuckoo in the Nest

Warning Signs

Thursday, 17 November

Guessing Games

White Lies

The Girl Who Never Cries

Truth or Dare

Sleeping Potion

Friday, 18 November

The Long Morning

The Ice Queen

The Old Friend

Dressing Up

The Builder’s Daughter

Evening Prayer

Saturday, 19 November

The Colour Red

The Man From Far Away

Tuesday, 14 February

Valentine’s Day

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Claire Kendal

About the Publisher

Late November

Eyes Like Yours

Somebody said recently that I have eyes like yours. Not just literally. Not just because they are blue. They said that I see like you too.

When I glimpse myself in the looking glass, your face looks out at me like a once-beautiful witch who is sickening under a curse. Those jewel eyes, losing their brightness. That pale skin and long black hair. It’s only the little pit by your left brow that isn’t there.

I see you everywhere.

If I really had eyes like yours, I wouldn’t be about to ask a question that you are going to hate. I would already know the answer. But here it is. What would you do if the police wanted to talk to you? Because I need to follow where you lead.

Just forming these words makes me see what to do. The police ask their questions and I am supposed to give them the answers they are hoping to hear. I am almost sorry for them, with their innocent faith that they can capture you on an official form, kept to a page or at most a few.

We wish to seek the whole truth, they say. You are a key witness, they say. We are concerned for your welfare, they say. We need to obtain the best evidence, they say. We will deal appropriately with the information you provide, they say. You can trust us, they say. The success of any subsequent prosecution will depend on accuracy and detail, they say. Other lives may be at stake, they say.

Am I supposed to be impressed? Flattered? Grateful? Scared? Intimidated? All of the above is my guess. So I will allow them to think that they have had their desired effect, as they take their careful notes and talk their tick-box talk in the calm and reassuring style that they have obviously rehearsed.

I will read the notes over to confirm their accuracy. I will appear to cooperate. I will sign the witness statement they prepare for me. I will date it too, with their help, because I have lost track of time a little, lately. Still, these motions are easy to go through. They do not matter.

What matters is that I am quietly writing my own witness statement, my own way, day after day. Compelled not by them but by you. That is what this is, and I am pretending that you are asking the questions and I am telling it all to you. I am writing down the things you want to know. The real things.

I will say this, though, Miranda, in my one concession to police speak. What follows comes from my personal knowledge of what I saw, heard and felt. I, Ella Allegra Brooke, believe that the facts in this witness statement are true. This is your story, but it is mine too, and I am our best witness. Maybe I do have eyes like yours, after all.

There is one more important thing I must tell you before I begin and it is this. It is that you mustn’t worry. Because I haven’t forgotten the confidentiality clause and I never will. You have taught me too well. What goes in this statement stays in this statement. It is for you alone. I am the sister of the sister and you are part of me. Wherever you are, I always will be. All my love, Melanie.

Saturday, 29 October

The Two Sisters

There is no visible sign that anything is out of place. But there is something wrong in the air, a mist of scent so faint I may be imagining it.

‘I was wondering,’ Luke says.

‘Wondering what?’ I am scanning every inch of our little clearing in the woods.

‘Why are so many fairy tales about sisters saving their brothers? All the ones you told me last week were.’

He is right. ‘Hansel and Gretel’. ‘The Seven Ravens’. ‘The Twelve Brothers’. Our mother seemed to know hundreds of them.

‘We should write a different story,’ I say.

‘I want one with a sister who saves her sister.’

I touch his cheek. ‘So do I.’

He marches straight into the centre of our clearing, dispersing any scent that might have lingered here.

This is where you and I used to make our own private house, playing together inside of walls made of tree trunks. We would eat the picnic lunches that Mum would bring out to us. We would plait each other’s hair and tickle each other’s backs.

When I think of your back, I see the milky skin beneath the tips of my fingers, my touch as light as a butterfly kiss. But this snapshot from our childhood disappears. Instead, I imagine your shoulder blade, and a flower drawn in blood. I hear you screaming. You are in a room below ground and I cannot get to you.

I blink several times in this weak autumn sun and remind myself of where I am and who I am with and that I cannot know that this is what happened.

I hear your voice. Even after ten years your words are with me. Find a different picture, you say. Remember the things that are real. This is what you used to tell me when I was scared that there was a monster underneath my bed.

I look around our clearing. This, I tell myself, is real. This is where Ted and I used to lie on a carpet of grass on summer days when we were children, holding hands and looking up through the gaps in the treetop roof. There would be snippets of blue sky and white cloud, and a pink snow of cherry blossom.

Your son is the most real thing of all. He bends down to scoop up a handful of papery leaves. ‘Hold your hands out,’ he says. When I do, he showers my palms with deep red. ‘Fire leaves,’ he says.

I shut out the flower made of blood. I manage to smile.

He cups a light orange pile. ‘Sun leaves,’ he says, throwing them high into the air and letting them rain upon us.

He finds green leaves, too. ‘Spring leaves,’ he says.

I lean over to choose some yellow leaves from our cherry tree, then offer them to Luke. ‘What do you call these?’

‘Summer leaves.’ This is when he blurts it out. ‘I want to live with you, Auntie Ella.’

I stare into Luke’s clear blue eyes, which are exactly like yours. When I zero in on them I can almost fool myself that you are here. And it hits me again. I imagine your eyes, wide open in pain and fear, your lashes wet with tears.

For the last few years, my waking nightmares about you have mostly been dormant. It took me so long to be able to control them. But a spate of fresh headlines last week shattered the defences I’d built.

Unsolved Case – New Link Discovered Between Evil Jason Thorne and Missing Miranda.

Eight years ago, when Thorne was arrested for torturing and killing three women, there was speculation that you were one of his victims. We begged the police for information. They would neither confirm nor deny the rumours, just as they refused to comment on the stories about what he did to the women. Perhaps we were too eager to interpret this as a signal that the stories were empty tabloid air. We were desperate to know what happened, but we didn’t want it to be Jason Thorne.

Dad spoke to the police again a few days ago, prompted by the fresh headlines. Once more they would neither confirm nor deny. Once more, Mum and Dad grabbed at anything which would let them believe that there was never any connection between you and Thorne. But I think they are only pretending to believe this to keep me calm, and their strategy isn’t working.

The possibility that Thorne took you seems much more real this time round. Journalists are now claiming that there is telephone evidence of contact between the two of you. They are also saying that Thorne communicated with his victims before stalking and snatching them. If these things are true, the police must have known all along, but they have never admitted any of it.

‘Don’t you want me?’ Luke says.

Thoughts of Jason Thorne have no business anywhere near your son.

‘Luke,’ I start to say.

He hears that something is wrong, though I reassure myself that he cannot guess what it really is. He walks in circles, kicking more leaves. They have dried in the lull we have had since yesterday’s lunchtime rain. ‘You don’t,’ he says.

Luke, you say. Focus on Luke.

I swallow hard. ‘Of course I do. I have always wanted you.’

Don’t think about my eyes, you say.

But everything is a trigger. I study Luke’s dark hair, so like ours, and imagine yours in Thorne’s hands, a tangle of black silk twining around his fingers.

How many times do I need to tell you to change the picture?

I try again to change the picture, but there is little in Luke that doesn’t visually evoke you. I search his face, and I am struck by the honey tint of his skin. Luke can actually tan, while you and Mum and Dad and I burn crimson and then peel.

He must have got this from The Mystery Man. I once teased you by referring to Luke’s father in this way, hoping it would provoke you into slipping out something about him. But all it provoked was a glare that I thought would vaporise me on the spot.

‘Granny and Grandpa and I have always been happy that we share you,’ I say. ‘It’s what your mummy wanted. You know that. She even made a will to make sure you’d be safe with us. She thought of that while you were still in her tummy.’

Luke wrinkles his nose to exaggerate his disdain. ‘In her tummy? I’m ten, not two, Auntie Ella.’

‘Sorry. When she was pregnant.’

But why? It is not the first time this question has nagged me. What made you make that will then? Were you simply being responsible? Do lots of people finally make a will when they are expecting a child? Or was it something more? Did you have a fear of dying while giving birth, however low pregnancy-related mortality may be in this country? If you did, you would have told me. I think you must have had other reasons for an increased sense of vulnerability. Jason Thorne is not the only possible solution to the puzzle of what happened to you.

Luke is waving a hand in front of my face. He is snapping his fingers. ‘Hello. Hello hello. Anyone in there?’

Whatever questions I may have, I tell him what I absolutely know to be true. ‘That was one of the many ways she showed how much she loved you, how much she considered you. But it’s complicated, the question of where you live. It isn’t the kind of decision you and I can make on our own.’

I don’t tell him how much our parents would miss him if he weren’t with them. Too much information, I hear you say.

He smiles in a way that makes me certain he knows the match is his, and he is amused that I am about to discover this. ‘If you share me then it shouldn’t make a difference if I live with you instead of them.’

‘True.’ There is nothing else I can say to that one, especially when I am enchanted by this new vision of having him with me all the time. I cannot help but smile and add, ‘You will be a barrister someday.’

‘No way. Policeman. Like Ted.’ He kicks the leaves harder. Fire and sun and spring and summer fly in all directions. But nothing derails your son. ‘I told Granny and Grandpa it’s what I want. They said they’d talk about it with you. They said it might be possible. They’re getting old, you know. And Grandpa could get sick again …’

‘Your grandpa is setting a record for the longest remission in human history.’

‘Okay.’

‘And Granny sat there calmly while you said all this?’

‘She cried a little, maybe.’

‘Maybe?’

‘Okay. Definitely. She tried not to let me see. But Grandpa said it might be better for me to be raised by someone younger.’

I’m sure our mother loved his saying that. No doubt Dad would have had several hours of silent treatment afterwards. Our mother is incapable of being straightforward at the best of times, and this is certainly not a topic she would want to pursue. She would have hoped it would go away if she didn’t mention it to me.

‘Then we will,’ I say. ‘Of course we’ll talk about it.’ He is not looking at me. ‘Can you stay still for a minute please, Luke?’

There is a rustling in the trees at the edge of the woods, followed by a breeze that lifts my hair from my face, then gently drops it.

Luke doesn’t notice, which makes me question my instinct that somebody is spying on us. Ever since we lost you I have imagined a man, hiding in the shadows, watching me, watching Luke. At least it cannot be Jason Thorne. He is locked away in a high-security psychiatric hospital.

I walk close to Luke, in case somebody really is ready to spring out at us. When the rustling grows nearer, he turns his head towards it. I am no longer in any doubt that I heard something. I put a hand on his shoulder and stand more squarely on both feet.

A doe pokes out her head, straightening her white throat and pricking up her ears to inspect us. She seems to be considering whether to turn back. All at once, she makes up her mind, crossing in front of us in two bounds, hardly seeming to touch the ground before she flees through the trees.

‘Wow,’ Luke says.

‘She was beautiful. Granny would say that seeing her was a blessing. A moment of grace is what she would call it.’

‘I can’t wait to tell Grandpa,’ Luke says.

I smooth Luke’s hair. ‘Happier now?’ He nods. ‘Are you going to tell me what brought on these new feelings about where you live?’

‘I want to go to that secondary school in Bath next year. Why would Granny take me to the open day and then not let me go? She said my preference mattered. But I won’t get in if she doesn’t use your address.’

‘Isn’t the application due on Monday?’

‘Yeah. But Granny keeps saying she’s still thinking about it. It should be my choice.’

‘With our guidance, Luke. It wouldn’t be fair to you otherwise – it’s too much of a responsibility for you to make this kind of decision by yourself. Granny never leaves things until the last minute, so she must still be weighing it all up very carefully. I’ll raise it with her and Grandpa after breakfast – I can see it’s urgent.’

‘It’s my life.’

‘Is that why you wanted this private walk before Granny and Grandpa are up? To talk about this?’

‘Yeah.’ He kicks again. ‘And before you say it, I don’t mind that none of my friends are going there. As Granny keeps reminding me.’

The school is perfect for Luke. It is seriously academic, and sits beside the circular park I’ve been taking him to since he was five. It’s also within reach of one of our favourite walks, along the clifftop overlooking the city. These are places he loves. Touchstones matter to Luke.

‘I want to be in Bath with you,’ he says. ‘Everything’s too far away from here.’

‘Stinky little lost village,’ I say.

He looks at me in surprise.

‘That’s what your mummy used to say.’

Would you be pleased by how hard I try to keep you present for him? How we all do?

I take his hand. ‘The school’s not as far away as it seems to you. It’s only a twenty-five-minute journey from Granny and Grandpa’s. Maybe you can live with me for half the week and Granny and Grandpa for the other half. I know we can work something out that everyone’s happy with.’

I promised Luke when I finally got a mortgage and moved out of our parents’ house that he would always have a room of his own with me. He was five then, and I nearly didn’t go, but our mother made me. ‘You need your own life,’ she said, squaring those ballerina shoulders of hers. ‘Your sister would want you to have a life. Miranda does not believe in self-sacrifice.’

I thought, then, that our mother was right. Because you certainly weren’t – aren’t – one for self-sacrifice.

Now, standing in our clearing with your son, I imagine you teasing me. Yeah. Because it suits you to believe it. So you can do what you want. Since when do you think our mother is right? Though the words are barbed, the voice is affectionate. The insight is there only because you apply the same filter to our mother that I use.

Luke turns back towards the woods. ‘Did you hear that, Auntie Ella? Like somebody coughed but tried to muffle it? It didn’t sound like our deer.’

I think of the interview I did a few months ago. Mum and Dad and I had always refused until then. But this was for a local newspaper, to publicise the charity. It seemed important to us, as the ten-year anniversary of your disappearance drew near. I talked about everything I do. The personal safety classes, the support group for family members of victims, the home safety visits, the risk assessment clinics.

There was no mention of you, but Mum and Dad were still worried by the caption that appeared beneath the photograph they snapped of me. Ella Brooke – Making a Real Difference for Victims. My arms are crossed and there is no smile on my face. My head is tilted to the side but my eyes are boring straight into the man behind the camera. I look like you, except for the severe ponytail and ready-for-action black T-shirt and leggings.

Could that photograph have set something off? Set someone off? Perhaps I hoped it would, and that was why I agreed to let them take it.

I catch Luke’s hand and pull him back to me. ‘Probably a rambler. It’s morning. It’s broad daylight. We are perfectly safe.’

‘So you don’t think it’s an axe murderer.’ He says this with relish, ever-hopeful.

‘Not today, I’m afraid.’

‘Well if it is, you’d kick their ass.’

‘Don’t let Granny hear you talk like that.’ The sun stabs me in the head – warmth and pain together – and I squeeze my eyes shut on it for a few seconds, trying at the same time to squeeze out the worry that somebody is watching us. I am also trying – and failing yet again – to lock out the images of what you would have suffered if Thorne really did take you.

‘Do you have a headache, Auntie Ella?’

Luke doesn’t know he pronounces it ‘head egg’. I find this charming, but I worry that he may be teased.

Should I correct him? I didn’t imagine I’d be buying up parenting books when I was only twenty, and that they would become my bedtime reading for the next decade. They don’t usually have the answers I need, but I know that you would.

‘No headache. Thank you for asking.’ I smile to show Luke that I mean it.

‘I think Mummy would like me to live with you.’

I love how he calls you Mummy. That’s how Mum and Dad and I speak of you to him. I wonder if we got stuck on Mummy because you never had time to outgrow it. Mummy is the name that people tend to use during the baby stage. You were never allowed to become Mum. Or mother, perhaps, though that always sounds slightly angry and over-formal.

‘If I live with you part of the time, can we get more of her things in my room?’

‘What things do you have in mind?’

‘Granny put her doll’s house up in the attic.’

‘It’s my doll’s house too.’ As soon as the words are out of my mouth, I realise that I sound like a little girl, fighting with you over a toy.

Luke smiles when he mimics our father’s reasoned tone. ‘Don’t you share it?’

‘Yes.’ I lift an eyebrow. ‘So you’d like a doll’s house?’

‘No. Of course not. I’m a boy. I don’t like doll’s houses.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with a boy liking doll’s houses.’

‘Well I don’t. But why would Granny put it out of the way like that?’

‘It hurt her to see it, Luke.’

He scowls. ‘It shouldn’t be hidden away in the attic. Get it back from her.’ He sounds like you, issuing a command that must be obeyed.

Three crows lift from a tree, squawking. Luke and I snap our heads to watch them fly off, so glossy and black they appear to have brushed their feathers with oil.

‘Do you think something startled them?’ He takes a fire leaf from his pocket.

‘Probably an animal.’

He is studying the leaf, tracing a finger over its veins. He doesn’t look at me when he says, super casually, ‘Can you make Granny give you that new box of Mummy’s things?’

There’s a funny little clutch in my stomach. I am not sure I heard him right. ‘What things?’

‘Don’t know. Stuff the police returned to Granny a couple weeks ago.’

‘Granny didn’t tell me that. How do you know?’

‘I’m a good spy. Like you. I heard her talking about them with Grandpa.’

‘Did Granny open it? Did she look in it?’

‘Not that she mentioned when I was listening.’

‘Did she say anything about why the police finally returned Mummy’s things?’

‘Nope. Get the box too. Make Granny give it to you.’

Getting that box is exactly what I want to do. Very, very much. ‘Okay,’ I say, though I mumble secretly to myself about the challenge of making our mother do anything. Our mother gives orders. She does not take them.

‘Auntie Ella?’

‘Yes.’

‘She would have come back for me if she could have, wouldn’t she?’

I think of one of the headlines that appeared soon after you vanished, claiming you’d run away. I put my arms around him tightly. We have always tried to protect him from such stories. Since last week’s spate of new headlines about Thorne, we have been monitoring Luke’s Internet use even more carefully. But we can’t know what he might have stumbled on, and I am nervous that a school friend has said something.

I kiss the top of his head and inhale. We have only been out for forty minutes but already he smells like a puppy who has run all the way back from a damp walk. ‘She would have come back for you.’ It is not raining but my cheeks are wet.

Luke wriggles out of my arms. He wipes at his cheeks too. ‘Are you sure?’

‘One hundred per cent. Nothing would have kept her from you if she had a choice.’

He bites his lower lip and looks down, scrunching his fists over his eyes.

Was I right to tell him these two true things, one beautiful and one too terrible to bear? That you were driven by your love for him, and that something unimaginably horrible happened to you?

Another thought creeps in, a guilty one. Is it easier for me to imagine you suffering a terrible death than to contemplate the possibility that you made a new life for yourself somewhere, as the police have sometimes suggested? I think of Thorne and shudder, absolutely clear that the answer is no.

‘She wanted you so much.’ It is extremely difficult to get these words out, but somehow I do, in a kind of croak.

‘It’s okay, Auntie Ella.’ He has so much courage, this boy, as he takes his fists from his eyes and comforts me when I should be comforting him. He waits for me to catch my breath. ‘I found a picture of her holding me,’ he says. ‘It’s one I hadn’t seen before. At first I thought it was you. You look like her.’

‘I think maybe that’s more true now than it used to be.’

‘Because you’re thirty now.’

‘Thanks for reminding me.’

‘I know. It’s really old.’

I stifle a mock-sob.

‘Sorry,’ he says.

‘You look stricken with remorse.’

‘I’m just saying it because now you’re her age. That’s why you’re looking so much more like her. You can see it in that newspaper picture of you too.’ He clears his throat. ‘Did you really try everything you could to find her?’

Did I? At first we barely functioned. Mum didn’t leave her bed. Dad stumbled around trying to make sure we had what we needed, cooking and cleaning and shopping, trying to get Mum to eat. I lurched through the house, trying to care for a two-and-a-half-month-old baby. Mostly we were reactive, answering the police questions, giving them access to your things. But we got in touch with everyone we could think of, did the appeals.

I stuck pictures of your face to lampposts, between the posters of missing cats and dogs. One of them stayed up for a year, fading as rain and wind and snow hit it, flapping at a bottom corner where the tape came off, dissolving at the edges but miraculously holding on.

I tell Luke as much of this as I can, as gently as I can, but he shakes his head.

‘I need you to try again,’ he says. ‘I need you to. I need to know. Even if it’s the worst thing, I need to.’ His voice rises with each sentence.

I grab a bottle of water from my jacket pocket and pass it to him. He gulps down half.

‘Is this why you want me to get her things from Granny?’

‘Yes.’ He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘You have to. Tell me you will. You have to look at everything.’

‘The police already did.’

‘No they didn’t. I hear much more than you think after I’ve gone to bed. I’ve heard all of you say how useless they are. Except Ted.’

I inhale slowly, then blow out air. ‘Okay.’

‘You’ll do it?’

I nod. ‘I will.’ My stomach drops as if I am running and an abyss has suddenly opened in front of me. Because there is something I can do that we haven’t tried before. I can request a visit with Jason Thorne. I reach for Luke’s hand. ‘But only on one condition.’

‘What?’

‘You will have to trust my judgement about what I can share with you.’