Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Damian Collins 2016

Damian Collins asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

‘Song-Books of the War’ and ‘Great Men’ copyright © Siegfried Sassoon by kind permission of the Estate of George Sassoon

Extract from Osbert Sitwell, Rat Week (Michael Joseph) by permission of David Higham Associates

Extract from Noël Coward, ‘Twentieth Century Blues’ copyright © NC Aventales AG 1931 by permission of Alan Brodie Representation Ltd, www.alanbrodie.com

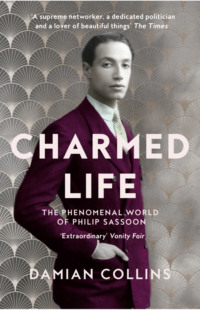

Cover photograph © National Portrait Gallery, London

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008127633

Ebook Edition © June 2016 ISBN: 9780008127619

Version: 2017-01-31

Dedication

For Sarah,

and her love, support and inspiration in all things

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE

1. Son of Babylon

2. The General’s Staff

3. Brave New World

4. Centre Stage

5. Flying Minister

6. Cavalcade

7. The Gathering Storm

8. The King’s Party

9. Philip Sassoon Revisited

PICTURE SECTION

FOOTNOTES

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

• PROLOGUE •

At dawn, long before the guests arrive, a cavalcade of horse-drawn carts makes the 14-mile journey from the flower market at Covent Garden, to the edge of north London and the gates of the Trent Park estate. Legions of gardeners are waiting to receive its colourful potted cargo ready for immediate planting, while the staff collect enough azaleas, roses and lilies to fill every room in the house. By noon there is a new procession, of Rolls-Royces arriving and departing in rapid succession. Everywhere along the approach there are signs with arrows guiding the drivers ‘To Trent’. Children and their parents line the route, hoping to catch a glimpse of a royal prince or a Hollywood star. The house and gardens have been profiled by Country Life, and the society columns regularly highlight the comings and goings of weekend guests. The Trent Park garden parties each June and July are considered the last word in elegance and luxurious informality.

Trent Park nestles in the ancient royal hunting ground of the Enfield Chase, where a broad, gentle valley is watered by a stream, creating a lake which divides the estate in two. The mansion is a fine Georgian-looking building with rose-coloured bricks and honeystone cornicing. It is a fantasy of a perfect eighteenth-century country estate, but supported by every modern convenience. In the drawing room, paintings by Gainsborough and Zoffany hang alongside Flemish tapestries. The floors are decorated with silk carpets from Isfahan, and Chinese lacquerwork sits alongside Louis XV furniture. In the Blue Room with its pale walls and accents of hot red, the contemporary artist Rex Whistler has just finished creating a mural above the fireplace which perfectly brings together the colours and elements of its surroundings.

The guests gather on the terrace, which is the heart of the party, and from where you can see right across the estate. People come and go as they please and white-coated footmen wearing red cummerbunds serve endless courses created by the resident French chefs. There is a restless atmosphere of constant activity. Winston Churchill is at the centre of the conversation, arguing with George Bernard Shaw about socialism, discussing art with Kenneth Clark and painting with Rex Whistler.

Flamingos and peacocks have been released from cages and move effortlessly between the gardens, terrace and house, mingling with the guests while Noël Coward plays the piano. And the host, the millionaire government minister and aesthete Sir Philip Sassoon, is in the midst of it all. He is a touch under 6 foot, with a handsome face, dark aquiline features and a smooth olive skin which makes him appear younger than his mid-forties. He is the creator of this tableau, and with meticulous attention to detail obsesses over every part of his production. Sassoon has an idiosyncratic and infectious style, always on the move, and is seen mostly in profile as he flits from guest to guest like a bee in search of honey.

Queen Mary and Philip’s sister Sybil, the Marchioness of Cholmondeley, lead the party in the formal gardens adjacent to the swimming pool and the orangery. Wide borders, laid out to the last square inch by the fashionable garden designer Norah Lindsay, lie in pairs on a gentle slope with broad grass paths on either side so that the eye can rove easily up this glade of brilliance. The incandescent orange and scarlet of the furthest beds give way to rich purples and blues in the middle distance, and the soft assuaging creams and pastel shades in the foreground. After the long borders are pergolas of Italian marble covered with vines, wisteria and clematis, where Winston Churchill likes to sit and paint on quieter afternoons.

The Prince of Wales arrives by aeroplane, landing at the Trent airstrip, and heads to the terrace where the American golf champion Walter Hagen is waiting to play a round with him on Sir Philip’s private course. The Duke of York and Anthony Eden, dressed for tennis, stride off with the professional to Trent’s courts. There is an air display by pilots from the RAF’s 601 Auxiliary Squadron, swooping and flying low over the estate. In the late afternoon, after the Queen has departed, the airmen join guests at the blue swimming pool, cavorting in the walled garden that surrounds it, filled with delphiniums and lilies, which deliver an almost overpowering scent.

The overnight guests withdraw to change for dinner, finding cocktails and buttonhole flowers waiting on their dressing tables as they put on their black tie. Philip Sassoon invites them to dine on the terrace, where Richard Tauber sings later by moonlight, and at the end of the evening there is a display of fireworks over the lake.

For guests reminiscing in the years to come, Philip’s lavish hospitality would seem like a dream of a lost world, the like of which would never be seen again. Yet even on this 1930s summer evening, amid the elegance and luxury of Trent Park, there is concern for the future. Among the politicians there is hard talk about Mussolini, Baldwin’s government, Germany’s threat and British rearmament. And this was not unusual. Almost every major decision taken in Britain between the wars was debated by those at the heart of the action while they were guests of Philip Sassoon.

Their host was more than just a wealthy patron and creative connoisseur. From the First World War through to 1939, Philip worked alongside Britain’s leaders and brought them together with some of the most brilliant people in the world. He exerted influence by design, while surrounded by an air of personal mystery.

1

• SON OF BABYLON •

One day, Haroun Al Raschid read

A book wherein the poet said: –

‘Where are the kings, and where the rest

Of those who once the world possessed?

‘They’re gone with all their pomp and show,

They’re gone the way that thou shalt go.

‘O thou who choosest for thy share

The world, and what the world calls fair,

‘Take all that it can give or lend,

But know that death is at the end!’

Haroun Al Raschid bowed his head:

Tears fell upon the page he read.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

‘Haroun Al Raschid’ (1878)1

The first thing that an English gentleman might consider about Sir Philip Sassoon was that he was foreign – an ‘oriental’2 in thought and action. His friend the art historian Kenneth Clark thought him to be ‘a kind of Haroun al Raschid, entertaining with oriental magnificence in three large houses, endlessly kind to his friends, witty, mercurial and ultimately mysterious’.3 The diarist and Sassoon’s fellow MP Henry ‘Chips’ Channon also observed, ‘Philip and I mistrust each other; we know too much about each other, and I can peer into his oriental mind with all its vanities.’4

To some extent Philip played up to this, and like the great Persian King Haroun Al Raschid from the tales of One Thousand and One Nights, he surrounded himself with beauty, luxury and the most interesting and successful people. No matter that he was also a baronet, the brother-in-law of a marquess and a Conservative Member of Parliament, his eastern heritage marked him out.

Philip Albert Gustave David Sassoon was born in Paris on 4 December 1888 at his mother’s family mansion in the Avenue de Marigny.fn1 He was the first child of Edward Sassoon and Aline, the daughter of Baron Gustave de Rothschild. His great-grandfather James Rothschild had been born into the Jewish ghetto in Frankfurt in 1792, and at the age of nineteen was sent by his father and brothers to establish the family business in France. When he died in 1868, James was one of the wealthiest men in the world. Ten thousand people attended his funeral and Parisians lined the streets to pay their respects when his coffin was taken for burial at the Père Lachaise cemetery.

The Sassoons were often referred to as the ‘Rothschilds of the east’. The family claimed that they were descended from King David, and that their ancestors had been transported to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar when he sacked Jerusalem, 600 years before the birth of Christ. They had kept their faith, and over the centuries established themselves as leaders in the exiled Jewish community, while also making money trading in the souks of Baghdad.

Young Philip Sassoon would grow up with the stories of how in 1828 his paternal great-grandfather David had been imprisoned in Baghdad by Dawud Pashafn2 during the suppression of the city’s Jews. David’s father Sasson ben Surah had been treasurer to the governor of the city and his wealth and connections helped him to buy his son’s freedom. David knew that his liberty would be short lived and so fled with only a money belt and some pearls sewn into the hem of his cloak. He went first by boat down the River Tigris to Basra, the port of the fabled Sinbad, and then secretly crossed the Persian Gulf to Bushire, safely beyond the reach of Pasha. Once established he sent for his family, including his eldest son, the ten-year-old Abdullah, future grandfather of Philip Sassoon. The town was the main trading post in Persia of the British East India Company, but it was a backwater compared with Baghdad. In one of Bushire’s dusty courtyards, with just a canopy to protect the congregation from the glare of the sun, Abdullah’s bar mitzvah was held among the traders, money-changers and pedlars of the local Jewish community. The Sassoon family’s good name and the trading skills they had acquired over the generations helped David to start to rebuild their fortunes, but he could see that greater opportunities existed further east in the emerging commercial centre of Bombay. It was there he moved in 1832, the year before the end of the East India Company’s monopoly on commerce in India, and established his business David Sassoon & Co., which grew into a major international trading empire – making the family, within his lifetime, one of the wealthiest in the world. As one contemporary remarked, ‘Silver and gold, silks, gums and spices, opium and cotton, wool and wheat – whatever moves over sea or land feels the hand or bears the mark of Sassoon & Co.’5

David Sassoon was an exotic figure in this boomtown of the British Raj. He continued to dress in the turban and flowing robes favoured by the great merchants of Baghdad. His wharfs and warehouses at the docks of Bombay were a veritable network of Aladdin’s caves holding the goods of the world: Indian cotton for Manchester, Chinese silks and furnishings for the mansions of Europe, and British manufactures for distribution throughout Asia. Twice married and with eight sons in total, David followed the model of the Rothschilds in Europe, using his children to keep close control of the expanding family business. Abdullah was initially sent back to Baghdad, now safe after the fall of Dawud Pasha in 1831, to manage the firm’s contacts in the Arab world. Elias would open the first Sassoon office in Shanghai, and their half-brothers Sassoon David (S. D.), Reuben and Abraham established themselves in Hong Kong.

David Sassoon was fluent in many Arab and Indian languages but never conducted business in English. However, he could see how vital Great Britain was to global trade, particularly in cotton and textiles, so in 1858 the twenty-six-year-old S. D. Sassoon, grandfather of the First World War poet Siegfried, was sent to open an office in London. England may have held no great appeal for the Sassoon patriarch, but his sons would become enthralled with life in the global centre of the British Empire. S. D. Sassoon took up residence in a fine fifteenth-century estate at Ashley Park in Surrey, where Oliver Cromwell was said to have lived during the trial of King Charles I. He opened the firm’s head office at 12 Leadenhall Street in the heart of the City of London, the same street where the great East India Company had based itself. Sassoon offices were also opened in Liverpool, the gateway for trade with America, and in ‘Cottonopolis’ itself – Manchester – at 42 Bloom Street. The family’s decision to come to England was made at exactly the right moment. The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 created an enormous demand from England for bales of cotton from India, as the traditional markets in the southern United States were closed by naval blockade. Bombay boomed and the fortunes of the Sassoons rose with it. When the American Civil War ended, and the cotton markets opened up again, many Indian traders went bust as prices fell. The Sassoons, though, had protected themselves, using their profits to make shrewd investments in property and developing trade with China. They were further strengthened by the comparative weakness of their Bombay competitors, many of whom had overextended themselves and were forced to sell up at rock-bottom prices when their loans were called in.

David Sassoon marked his new wealth by building a great palace for the family in Poona, about 100 miles inland from Bombay, where the British took up residence during the monsoon season. He called it Sans Souci, after the estate created by Frederick the Great near Potsdam in Germany. He also became one of the leading philanthropists of Poona and Bombay, endowing hospitals, schools and synagogues.

As David Sassoon started to draw back from his day-to-day involvement in the business, his sons began to dress as British gentlemen, rather than in the traditional Arabic costume their father favoured. Abraham Sassoon encouraged people to call him the more English-sounding Arthur. Abdullah also preferred to be addressed as Albert, and named his son Edward, after the Prince of Wales. When David Sassoon died in 1864, Albert took over as chairman of the company but much of the day-to-day running of the business was left to his brothers. Fate played a further part in the direction followed by members of the family when in 1867 S. D. Sassoon collapsed and died in the lobby of the Langham Hotel in London. Albert sent Reuben from Hong Kong to take over affairs in England, and to look after S. D.’s young family at Ashley Park. In 1872 Reuben was joined in London by Arthur and his beautiful new wife Louise, and the brothers soon made their mark on society. In addition to homes in the capital and on the coast at Hove, Arthur took possession of Tulchan Lodge, the Speyside estate in Scotland where he entertained the Prince of Wales at shooting parties. The loyalty, discretion and generosity of the Sassoon brothers won them the favour and friendship of the Prince, who was a man of great appetites, though without the necessary resources to supply them.

Back in India, Albert Sassoon pursued his chief interest of consolidating the family’s position in political society, a path that both his son Edward and grandson Philip would also follow. Albert created the ‘David Sassoon Mechanics Institute and Library’ which still stands in the city, served on the Bombay Legislative Council and was made a Companion of the Order of the Star of India for his philanthropic works in the city, the highest British order of chivalry in India.

In 1875 Albert Sassoon was central to business and official life in Bombay. He opened the vast Sassoon Docks, the first commercial wet dock in western India, and threw a magnificent ball at Poona for Edward, the Prince of Wales to honour his official visit. Afterwards Albert presented to Bombay a 13-foot-tall equestrian statue of the Prince. It was placed in front of the David Sassoon Library and became known as the Kala Ghoda, meaning Black Horse in Hindi, a title which was subsequently used to describe that neighbourhood of the city.fn3

However, the success of Edward’s visit, combined with the letters back to Bombay from his brothers, made Albert increasingly keen to join them permanently in England. London promised a more glamorous life, and it could be justifiably argued that the chairman of David Sassoon & Co. should be based there. He took up residence in a mansion at 25 Kensington Gore and at a large summer house in Brighton, near to Arthur’s home in Hove.

Brighton would be the scene of the greatest of his royal entertainments, when Albert was persuaded to take over the arrangements for a grand reception for the state visit of the Shah of Persia, Nasr-ed-Din, in July 1889. His mansion on the Eastern Terrace was not large enough to accommodate everyone, so the Empire Theatre was hired for the occasion. He spent liberally on the decorations, on refreshments and on a programme of ballet to entertain the guests, who included members of the royal family. For Albert, it was a long way from his bar mitzvah, as a young immigrant in that dusty town on the Persian coast, nearly sixty years before.

Nasr-ed-Din was a difficult man, but Albert’s hospitality had been a triumph for which his reward from a grateful British state was a baronetcy. The College of Heralds helped Sir Albert Sassoon to create a coat of arms comprising symbols appropriate to the family’s heritage: the lion of Judah carrying the rod that was never to depart from their Jewish tribe; a palm tree representing the flourishing of the righteous man; and a pomegranate, a rabbinical symbol of good deeds.

On 24 October 1896, Philip Sassoon, just a few weeks short of his eighth birthday, would learn of the sudden death of his grandfather, and would then see him interred in the domed mausoleum which Albert had recently constructed for the family, close to his Brighton mansion.fn4 Philip’s father inherited the chairmanship of the family firm, as well as Albert’s title, and so became Sir Edward Sassoon, second baronet of Kensington Gore. Free from the expectation that he would devote himself to the family business, Edward had been brought up to be an English gentleman. He had studied for a degree at the University of London, went shooting with the Prince of Wales at Tulchan and became an officer in a Yeomanry regiment, the Duke of Cambridge’s Hussars. In October 1887 Edward’s marriage to the French heiress Aline de Rothschild was conducted at the synagogue on the Rue de la Victoire in Paris by the Chief Rabbi of France. Twelve hundred guests attended the reception at the Rothschilds’ palatial home on the Avenue de Marigny, and this great dynastic union further consolidated the Sassoons’ standing in European society. The Prince of Wales was often a guest of the Rothschilds at the Avenue de Marigny during his frequent trips to Paris, and Edward and Aline Sassoon became established as part of his circle of close friends known as the Marlborough House set.

Edward Sassoon was tall and handsome, with a ‘sharp grim look which vanished when he smiled’.6 He was an enthusiastic sportsman, who took particular pleasure in shooting, ice skating at St Moritz and playing billiards. Aline combined beauty and elegance with great intelligence. She brought from Paris her love of art and literature, a passion that she would share with their children, Philip and his younger sister Sybil, born six years after him in 1894. Edward and Aline created their own salon, selling Albert’s Kensington Gore house and purchasing a larger mansion at 25 Park Lane, which had originally been built for Barney Barnato, the London-born Jewish diamond magnate.fn5 Aline became a popular society hostess in England and France and the children would grow up around the parties thrown for her wide circle of friends, who included Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells and John Singer Sargent, who painted her. Aline was also one of the ‘Souls’, an elite social group for political and philosophical discussion whose members included the politician Arthur Balfour, Margot Asquith, the wife of Herbert Asquith, and another great hostess of the period, Lady Desborough.

The Sassoon family interest in politics was as strong for Edward as it had been for his father, and in 1899 an opportunity came to stand for election to the House of Commons as the Unionist candidate in a by-election for the Hythe constituency. His selection for the seat was easier because it was considered to be a ‘pocket borough’ of his wife’s family. Her father’s cousin Mayer de Rothschild had been its MP for fifteen years until his death in 1874 and the family still made generous annual contributions to the local party funds.fn6 This south Kent constituency consisted of the ancient Cinque Port towns of Hythe and New Romney, as well as the fashionable resort of Folkestone, which was also a favourite of the Prince of Wales. The district embraced the wide, flat Romney Marsh, farmed since the Middle Ages when it was recovered from the sea, and which in centuries past had harboured gangs of smugglers. Following his successful election campaign Edward bought Shorncliffe Lodge as a home for his family in the constituency, a fine white-stuccoed house which stood on the Undercliff in Sandgate, a village along the coast from Folkestone. The house commanded views around Hythe Bay, and on a clear day you could see across the English Channel to France. Philip and Sybil’s childhood would be spent between Park Lane and seaside holidays on the Kent coast, with frequent visits to their mother’s family at the Avenue de Marigny and the Rothschild Château de Laversine near Chantilly.

Sir Edward Sassoon did not shine as a parliamentarian. He became an established backbench MP who took an interest in trade, improving international telegraph communications and the idea of building a Channel tunnel. His place in the House of Commons, the mother parliament of the British Empire, may have enhanced his standing in political society, but it was not somewhere he needed to be. He was paving the way for his children so that they could go on and attain the heights of power and prominence in the British establishment that for him were out of reach. Like all parents, he was ambitious for his children, and he clearly hoped that Philip would use the wealth, title and connections he would inherit to launch his own great career in British public life.

The formal education Edward and Aline chose for Philip was one they hoped would equip him to be a leading member of the British ruling class. He attended a boarding prep school in Farnborough, before being sent to Eton College. Fathers put their sons down for a place at Eton on the day or at least in the week of their birth. In the early 1900s the purpose of the school’s entrance exam was not to select the best students, but to determine into which form a boy should be placed. After Eton Philip would spend four years at the University of Oxford, where many of the young undergraduates would attend the same college as previous generations of their families, often inhabiting the same set of rooms. This was the tried and tested production line designed to mould the future elite, one that had produced in good order prime ministers, generals and colonial governors. When Philip started at Eton in spring 1902, the then Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was among the school’s alumni, as had been his immediate three predecessors going back over twenty years. Edward wrote to tell his son as he embarked upon his school life that ‘You will find diligence in studies particularly helpful when you join the Debating Society at Eton, an institution in which excellence means a brilliant career in Parliament later on.’7

Philip was the first generation of his line of the Sassoon family to receive his schooling in England, although he did have five cousins at Eton, all members of the Ashley Park branch, and grandsons of S. D. Sassoon.fn7 There were other boys he knew from his mother’s circle, particularly Julian and Billy Grenfell, and Edward Horner, the sons respectively of Lady Desborough and Frances Horner. Eton would not be a complete leap into the unknown for Philip, but nor was he a native of his new habitat.

Arriving for his first term, the thirteen-year-old Philip Sassoon was an exotic figure to those English schoolboys. He had a dark complexion, as a result of his eastern heritage, and a French accent from the great deal of time he had spent with his mother’s family. In particular he rolled his ‘r’s and at first introduced himself with the French pronunciation of his name: ‘Pheeleep’. Philip had a slight build which did not mark him out as a future Captain of Boats or star of the football field; Eton was a school which idolized its sportsmen, and they filled the ranks of Pop, the elite club of senior boys. For Philip, just being Jewish made him unusual enough in the more conservative elements of society, as it aroused suspicion as a ‘foreign’ religion.

While it was well known that Philip’s family had great wealth, this was not something that would necessarily impress the other boys, particularly when it was new money. Any sense of self-importance was also strictly taboo, and likely to lead only to ridicule. To be accepted, Philip would need to master that great English deceit of false modesty.

He was placed in the boarding house run by Herbert Tatham, a Cambridge classicist who had been a member of one of the university’s secret societies of intellectuals, the Young Apostles. The house accommodation was spartan, and certainly bore no comparison with Philip’s life in Park Lane and the Avenue de Marigny. Lawrence Jones, a contemporary at Eton, where his friends called him ‘Jonah’, remembered that in his house:

no fires might be lit in boys’ rooms till four o’clock, however hard the frost outside, and since the wearing of great coats was something not ‘done’ except by boys who had house colours or Upper Boats, we shook and shivered from early school till dinner at two o’clock … we snuffled and snivelled through the winter halves … If there is anything more bleak than to return to your room on a winter’s morning, with snow on the ground to find the door and window open, the chairs on the table and the maid scrubbing the linoleum floor, I have not met it.8

Unlike many other English boarding schools of the time, boys at Eton had a room to themselves from the start, which gave them a place to escape to and a space which they could make their own. This was one definite advantage and Jones recalled that ‘For sheer cosiness, there is nothing to beat cooking sausages over a coal fire in a tiny room, with shabby red curtains drawn, and the brown tea-pot steaming on the table.’9 There were dangers too in these cramped old boarding houses, and in Philip’s first year at the school a terrible fire would destroy one of them, killing two junior boys.

One of the senior boys in Philip’s house was the popular Captain of the School, Denys Hatton, who took him under his wing when he started. Denys would not allow Philip to be bullied, and in return he received overwhelming displays of gratitude and admiration which at times clearly disturbed him. On one occasion when Denys was laid up in the school infirmary with a knee injury, Philip rushed to his side with lavish gifts including a pair of diamond cufflinks and ruby shirt studs. Denys received them with disgust, throwing them on to the floor, but he later made sure to retrieve them.10 Philip remembered Denys’s kindness, and when he had himself risen through the school’s ranks he was similarly considerate to the junior boys. At Eton it was the tradition for the juniors to act as servants or ‘fags’ for senior students. Osbert Sitwell, the future writer and poet, fulfilled this role for Philip and they remained friends thereafter. Sitwell remembered that Philip was ‘very grown up for his age, at times exuberant, at others melancholy and preoccupied, but always unlike anyone else … And extremely considerate and kind in all his dealings.’11