Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

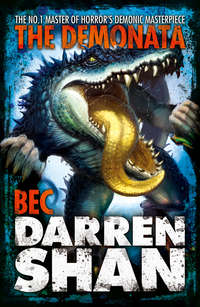

Kitabı oku: «Bec»

Scream in the dark on the web at

www.darrenshan.com

For:

Bas, the priestess of Shanville

OBEs (Order of the Bloody Entrails) to:

Emma “Morrigan” Bradshaw

Geraldine “sarsaparilla” Stroud

Mary “Macha” Byrne

Hewn into shape by:

Stella “seanachaidh” Paskins

Fellow questers:

the Christopher McLittle clan

Contents

Beginning

Casualties

Refugees

The Boy

The River

The Stones

The Crannog

Drust

Potential

An Uninvited Guest

Children of the Dark

Family

The Source

The Emigrants

The Geis

Old Creatures

Taming the Wild

The Final Day

The World Beneath

The Sacrifice

Escape

Full Circle

Celtic Terms and Phrases

Other Books by Darren Shan

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

BEGINNING

→ Screams in the dark.

Mother pushes and after a long fight I slip out of her body on to a bed of blood-soaked grass. I cry from the shock of cold air as I take my first breath. Mother laughs weakly, picks me up, holds me tight and feeds me. I drink hungrily, lips fastened to her breast, my tiny hands and feet shivering madly. Rain pelts us, washing blood from my wrinkled, warm skin. Once I’m clean, mother shields me as best she can. She’s weary but she can’t rest. Must move on. Kissing my forehead, she sighs and struggles to her feet. Stumbles through the rain, tripping often and falling, but protecting me always.

→ Banba never believed I could remember my birth. She said it was impossible, even for a powerful priestess or druid. She thought I was imagining it.

But I wasn’t. I remember it perfectly, like everything in my life. Coming into this world roughly, in the wilderness, my mother alone and exhausted. Clinging to her as she pushed on through the rain, over unfamiliar land, singing to me, trying to keep me warm.

My thoughts were a jumble. I experienced the world in bewildering fragments and flashes. But even in my newborn state of confusion I could sense my mother’s desperation. Her fear was infectious, and though I was too young to truly know terror, I felt it in my heart and trembled.

After endless, pain-filled hours, she collapsed at the gate of a ringed, wooden fort — the rath where I live now. She didn’t have the strength to call for help. So she lay there, in the water and mud, holding my head up, smiling at me while I scowled and burped. She kissed me one last time, then clutched me to her breast. I drank greedily until the milk stopped. Then, still hungry, I wailed for more. In the damp, gloomy dawn, Goll heard me and investigated. The old warrior found me struggling feebly, crying in the arms of my cold, stiff, lifeless mother.

“If you remember so much, you must remember what she called you,” Banba often teased me. “Surely she named her little girl.”

But if she did give me a name, she never said it aloud. I don’t know her name either, or why she died alone in such miserable distress, far from home. I can remember everything of my own life but I know nothing of hers, where I came from or who I really am. Those are mysteries I don’t think I’ll ever solve.

→ I often retreat into my early memories, seeking joy in the past, trying to forget the horrors of the present. I go right back to my first day here, Goll carrying me into the rath and joking about the big rat he’d found, the debate over whether I should be left to die outside with my mother or accepted as one of the clan. Banba testing me, telling them I was a child of magic, that she’d rear me to be a priestess. Some of the men were against that, suspicious of me, but Banba said they’d bring a curse down on the rath if they drove me away. In the end she got her way, like she usually did.

Growing up in Banba’s tiny hut. Everybody else in the rath shares living quarters, but a priestess is always given a place of her own. Lying on the warm grass floor. Drinking goat’s milk, which Banba squeezed through a piece of cloth. Staring at a world which was sometimes light, sometimes dark. Hearing sounds when the big people moved their lips, but not sure what the noises meant. Not understanding the words.

Crawling, then walking. Growing in body and mind. Learning more every day, fitting words together to talk, screeching happily when I got them right. Realising I had a name—Bec. It means ‘Little One’. It’s what Goll called me when he first found me. I was proud of the name. It was the only thing I owned, something nobody could ever take from me.

As I grew up, Banba trained me, teaching me the ways of magic. I was a fast learner, since I could remember the words of every spell Banba taught me. Of course, there’s more to magic than spells. A priestess needs to soak up the power of the world around her, to draw strength from the land, the wind, the animals and trees. I wasn’t so good at that. I doubted I’d ever make a really strong priestess, but Banba said I’d improve in time, if I worked hard.

I discovered early on that I’d never fit in. The other children were wary of the priestess’s apprentice. Their mothers warned them not to hurt me, in case I turned their eyes into runny pools or their teeth into tiny squares of mud. I was sad that I couldn’t be one of them. I asked Banba where I came from, if there was a place I could go where I’d be more welcome.

“Priestesses are welcome nowhere,” she answered plainly. “Folk are pleased to have us close, so they can call on us when the crops fail or a woman can’t get round with child. But they never truly trust us. They don’t take us into their confidence unless they have to. Better get used to it, Little One. This is our life.”

The life wasn’t so bad. There was always plenty of food for a priestess, from people eager to win her favour and avoid a nasty curse. And there was respect, and gifts when I made spells work. People wondered how powerful I’d become and what I could do to make the rath stronger. Banba often laughed about that — she said people were always either too suspicious or expected too much.

A few treated me normally, like Goll of the One Eye. Chief of the rath once, now just an ageing warrior. He didn’t care that I was a stranger, from no known background, studying to be a priestess. I was simply a little girl to him. He even spoilt me sometimes, since in a way he felt like my father, as he was the one who found and named me. He often played with me, put me up on his broad shoulders and gave me rides around the rath, grunting like a pig while others laughed or sneered. All the children loved Goll. He was a fierce warrior, who’d killed many men in battle, but he was still a child secretly, in his heart.

Those were the best days. Dreaming of the magic I’d work when I grew up. Harvesting the crops. Herding cattle and sheep. I wasn’t supposed to do ordinary work, but if a child was lazy and I offered to help, they usually let me. Some even became friends over time. They wouldn’t admit it in front of their mothers or fathers, but when nobody was looking they’d talk to me and include me in their games.

Playing… working… learning the ways of magic. Good times. Simple times. Life going on the way it had since the world began, like it was meant to.

Then the demons came.

CASUALTIES

→ A boy’s screams pierce the silence of the night and the village explodes into life. Warriors are already racing towards him by the time I whirl from my watching point near the gate. Torches are flung into the darkness. I see Ninian, a year younger than me, new to the watch… a two-headed demon, pieced together from the bones and flesh of the dead… blood.

Goll is first on the scene. An old-style warrior, he fights naked, with only a small leather shield, a short sword and axe. He hacks at the demon with his axe and buries it deep in one of the monster’s heads. The demon screeches but doesn’t release Ninian. It lashes out at Goll with a fleshless arm and knocks him back, then buries the teeth of its uninjured head in Ninian’s throat. The screams stop with a sickening choking sound.

Conn and three other warriors swarm past Goll and attack the demon. It swings Ninian at them like a club and scythes two of them down. Conn and another keep their feet. Conn jabs one of the monster’s eyes with his spear. The demon squeals like a banshee. The other warrior – Ena – slides in close, grabs the beast’s head and twists, snapping its neck.

If you break a human’s neck, that person will almost surely die. But demons are made of sturdier stuff. Broken necks just annoy most of them.

With one hand the demon grabs the head which Goll shattered with his axe. Rips it off and batters Ena with it. She doesn’t let go. Snaps the neck again, in the opposite direction. It comes loose and she drops it. She pulls a knife from a scabbard strapped to her back and drives it into the rotting bones of the skull. Making a hole, she wrenches the sides apart with her hands, digs in and pulls out a fistful of brains. Grabs a torch and sets fire to the grey goo.

The demon howls and grabs blindly for the burning brains. Conn snatches the other head from its hand. He throws it to the ground and mashes it to a pulp with his axe. The demon shudders, then slumps.

“More!” comes a call from near the gate. It’s late — later than demons usually attack. Most of the warriors on the main watch have retired for the night, replaced by children like me. Our eyes and ears are normally sharp. But this close to dawn, most of us are sleepy and sluggish. We’ve been caught off guard. The demons have snuck up. They have the advantage.

Bodies spill out of huts. Hands grab spears, swords, axes, knives. Men and women race to the rampart. Most are naked, even those who normally fight in clothes — no time to get dressed.

Demons pound on the gate and scale the banks of earth outside, tearing at the sharpened wooden poles of the fence, clambering over. The two-headed monster might have been a diversion, sent to distract us. Or else it just had a terrible sense of direction, as many corpse-demons do.

Warriors mount ladders or haul themselves up on to the rampart to tackle the demons. It’s hard to tell how many monsters there are. Definitely five or six. And at least two are real demons — Fomorii.

Conn arrives at the gate, shouting orders. He bellows at those on watch who’ve strayed from their posts. “Stay where you are! Call if clear!”

The trembling children return to their positions and peer into the darkness, waving torches over their heads. In turn they yell, “Clear!” “Clear!” “Clear!” One starts to shout “Cle–”, then screams, “No! Three of them over here!”

“With me!” Goll roars at Ena and the others who fought the first demon. They held back from the battle at the gate, in case of a second attack like this. Goll leads them against the trio of demons. I see fury in his face — he’s not furious with the demons, but with himself. He made a mistake with the first one and let it knock him down. That won’t happen again.

As the warriors engage the demons, I move to the centre of the rath and wait. I don’t normally get involved in fights. I’m too valuable to risk. If the demons break through the barricades, or if an especially powerful Fomorii comes up against us — that’s when I go into action.

To be honest, I doubt I could do much against the stronger Fomorii. Everybody in the rath knows that. But we pretend I’m a great priestess, mistress of all the magics. The lie comforts us and gives us some faint shadow of hope.

The younger children of the rath cluster around me, watching their parents fight to the death against the foul legions of the Otherworld. Their older brothers and sisters are at the foot of the rampart, passing up weapons to the adults, ready to dive into the breach if they fall. But these young ones wouldn’t be of much use.

I hate standing with them. I’d rather be at the rampart. But duty comes at a price. Each of us does what we can do best. My wishes don’t matter. The welfare of the rath and my people comes first. Always.

One of the Fomorii makes it over the fence. Half-human, half-boar. A long jaw. A mix of human teeth and tusks. Demonic yellow eyes. Claws instead of hands. It bellows at the warriors who go up against it, then spits blood at them. The blood hits a woman in the face. She shrieks and topples back off the rampart. Her flesh is bubbling — the demon blood is like fire.

I race to the woman. It’s Scota. We share a hut sometimes (I’m passed around from hut to hut now Banba’s gone). Her usually pale skin is an ugly red colour. Bubbles of flesh burst. The liquid sizzles. Scota screams.

I press my palms to her forehead, ignoring the heat of her flesh and the burning drops of liquid which strike my skin. I mutter the words of a calming spell. Scota sighs and relaxes, eyes closing. I tug a small bag from my belt, open it and pour coarse green grains into the palm of my left hand. Dropping the bag, I spit over the grains and mix them together with a finger, forming a paste. I rub the paste into Scota’s disfigured flesh and it stops dissolving. She’ll be scarred horribly but she’ll live. There are other pastes and lotions I can use to help the wounds heal cleanly. But not now. There are demons to kill first.

I look up. The boar demon has been pierced in several places by the swords and knives of our warriors, but still it fights and spits. I wish I knew where these monsters got their unnatural strength from.

Screams behind me — the children! A spider-shaped Fomorii has crawled out of the hut over the souterrain. The beast must have found the exit hole outside the rath and made its way up the tunnel, then broke through the planks covering the entrance.

Conn hears the screams. He looks for warriors to send to their aid. Before he can roar orders, two brothers hurl themselves into the demon’s path. Ronan and Lorcan, the rath’s red-headed twins, barely sixteen years old. Their younger brother, Erc, was killed several months ago. The twins were always strong fighters, even as young children, but since Erc fell, they’ve fought like men possessed. They love killing demons.

Conn refocuses on the demons at the gate. He doesn’t bother sending other warriors to deal with the spider. He trusts the teenage twins. They might be among the youngest warriors in the rath, but they’re two of the fiercest.

Ronan and Lorcan move in on the spider demon. Now that it’s closer, I see that although it has the body of a large spider, it has a dog’s face and tail. Demons are often a mix of animals. Banba used to say they stole the forms of our animals and ourselves because they didn’t have the imagination to invent bodies of their own.

Ronan, the taller of the pair, with long, curly, flowing hair, has two curved knives. Lorcan, who cuts his hair close and whose ears are pierced with a variety of rings, carries a sword and a small scythe. They’re both skilled at fighting with either the left or right hand. But before they can tackle the dog-spider, it shoots hairs at them. The hairs run all the way along its eight legs and act like tiny arrows when flicked off sharply.

The hairs strike the brothers and cause them to stop and cover their faces with their hands, to protect their eyes. They hiss, partly from the pain, but mostly with frustration. The Fomorii moves forward, barking with evil delight, and the twins are forced back, chopping blindly at it.

I could call Conn for assistance, but I want to handle this on my own. I won’t place myself at risk, but I can help, leaving the warriors free to concentrate on the larger, more troublesome demons.

I hurry to the beehives. We kept them outside the rath before the attacks began, but certain demons have a taste for honey, so we moved them in. The bees are at rest. I reach within a hive and grab a handful of bees, then prise them out, whispering words of magic so they don’t sting me. Walking quickly, I place myself behind Ronan and Lorcan. Taking a firm stance, I thrust my hand out and whisper to the bees again, a command this time. They come to life within my grasp.

“Move!” I snap. Ronan and Lorcan glance back at me, surprised, then step aside. I open my fingers and the bees fly straight at the dog-spider, attacking its eyes, stinging it blind. The Fomorii whines and slaps at its eyes with its legs, losing interest in everything except the stinging bees. Ronan and Lorcan step up, one on either side. Four blades glint in the light of the torches — and four hairy legs go flying into darkness.

The demon collapses, half its legs gone, sight destroyed. Ronan steps on its head, takes aim, then buries a knife deep in its brain. The dog-spider stiffens, whines one last time, then dies. Ronan withdraws his knife and wipes it clean on his long hair. His natural red hair is stained an even darker shade of red from the blood of demons. Lorcan’s stubble is blood-caked too. They never wash.

Ronan looks at me and grins. “Nice work.” Then he runs with Lorcan to where Conn and his companions are attempting to drive the demons back from the fence.

I take stock. Goll’s section is secure — the demons are retreating. The boar-shaped Fomorii has been pushed back over the fence. It’s clinging to the poles, but its fellow demons aren’t supporting it. When Ronan and Lorcan hit, blades turning the air hot, it screams shrilly, then launches itself backwards, defeated. Connla – Conn’s son – fires a spear after the demon. He yells triumphantly — it must have been a hit. Connla picks up another spear. Aims. Then lowers it.

They’re retreating. We’ve survived.

Before anyone has a chance to draw breath, there’s a roar of rage and loss. It comes from near the back of the rath — Amargen, Ninian’s father. He’s cradling the dead boy in his arms. He had five children once. Ninian was the last. The others – and his wife – were all killed by demons.

Conn hurries across the rampart towards Amargen, to offer what words of comfort he can. Before Conn reaches him, Amargen leaps to his feet, eyes mad, and races for the chariot which our prize warriors used when going to fight. It’s been sitting idle for over a year, since the demon attacks began. Conn sees what Amargen intends and leaps from the rampart, roaring, “No!”

Amargen stops, draws his sword and points it at Conn. “I’ll kill anyone who tries to stop me.”

No bluff in the threat. Conn knows he’ll have to fight the crazed warrior to stop him. He sizes up the situation, then decides it’s better to let Amargen go. He shakes his head and turns away. Waves to those near the gate to open it.

Amargen quickly hooks the chariot – a cart really, nothing like the grand, golden chariots favoured by champions in the legends – up to a horse. It’s the last of our horses, a bony, exhausted excuse for an animal. He lashes the horse’s hind quarters with the blunt face of his blade and it takes off at a startled gallop. Racing through the open gate, Amargen chases the demons and roars a challenge. I hear their excited snorts as they stop and turn to face him.

The gate closes. A few of the people on the rampart watch silently, sadly, as Amargen fights the demons in the open. Most turn their faces away. Moments later — human screams. A man’s. Terrible, but nothing new. I say a silent prayer for Amargen, then turn my attention to the wounded, hurrying to the rampart to see who needs my help. The fighting’s over. Time for healing. Time for magic. Time for Bec.

REFUGEES

→ No clouds. The clearest day in a long time. Good for healing. I take power from the sun. It flows through me and from my fingers to the wounded. I use medicine, pastes and potions where they’re all that’s needed. Magic on those with more serious injuries — Scota and a few others who were struck by the Fomorii’s fire-blood.

The warriors are tired, their sleep disturbed. They’ll rest later, but most are too edgy to return to their huts straightaway. It takes an hour or two for the battle lust to pass. They’re drinking coirm now and eating bread, discussing the battle and the demons.

I’m fine. I had a full night’s sleep, only coming on watch a short while before the attack. That’s my regular pattern on nights when there isn’t an early assault.

Having tended to the seriously wounded, I wander round the rath, in case I’ve missed anybody. I used to think the ring fort was huge, ten huts contained within the circular wall, plenty of space for everyone. Now it feels as tight as a noose. More huts have been built over the last year, to shelter newcomers from the neighbouring villages in our tuath. Many of those who lived nearby were forced out of their homes and fled here for safety. There are twenty-two huts now, and although the walls of the rath were extended outwards during the spring, we weren’t able to expand by much.

The use of magic has wearied me and left me hungry. I don’t have much power, nothing like what Banba had. The sun helps but it’s not enough. I need food and drink. But not coirm. That would make me dizzy and sick. Milk with honey stirred in it will give me strength.

Goll’s sitting close to the milk pails. He looks downhearted. He’s scratching the skin over his blind right eye. Goll was king of this whole tuath years ago, the most powerful man in the region, with command of all the local forts. There was even talk that he might become king of the province — our land is divided into four great sectors, each ruled by the most powerful of kings. None of our local leaders had ever held command of the province. It was an exciting prospect. Goll had the support of every king in our tuath and many in the neighbouring regions. Then he lost his eye in a fight and had to step down. He’s not bitter. He never talks of what might have been. This was his fate and he accepts it.

But Goll’s in a gloomy mood this morning. He hates making mistakes. Feeling sorry for the old warrior, I sit beside him and ask if he wants some milk.

“No, Little One,” he says with a weak smile.

“It wasn’t your fault,” I tell him. “It was a lucky strike by the Fomorii.”

Goll grunts. That should be the end of it, except Connla is standing nearby, a mug of coirm in his hands, boasting of the demon he hit with his spear. He hears my comment and laughs. “That wasn’t luck! Goll’s a rusty old goat!”

Goll stiffens and glares at Connla. Eighteen years old, unmarried Connla’s one of the handsomest men in the tuath, tall and lean, with carefully braided hair, a moustache, no beard, fashionable tattoos. His cloak is fastened with a beautiful gold pin, and pieces of fine jewellery are stitched into it all over. Unlike most of the men, who wear belted tunics, he favours knee-length trousers. He was the first man in the rath to wear them, although several have followed his lead. His boots are made from the finest leather, laced artistically with horse-hair thongs. He looks more like a king than his father does, and when Conn dies he’ll be one of the favourites to replace him. Most of the young women in the tuath desire him for his looks and prospects. But he’s no great warrior. Everyone knows Connla’s an average fighter. And far from the bravest.

“At least I was there to make a mistake,” Goll growls. “Where were you, Connla — combing your hair perhaps?”

“I was in the thick of the fighting,” Connla insists. “I struck a demon. I think I killed it.”

“Aye,” Goll sneers. “You hit it with a spear. In the back. While it was running away.” He claps slowly. “A most courageous deed.”

Connla hisses. His hand goes for a spear. Goll snatches for his axe.

“Enough!” Conn barks. He’s been keeping an eye on the pair. He always seems to be on hand when Connla’s on the point of getting into trouble. The king steps forward, scowling. “Isn’t it bad enough that we have to fight demons every night, without battling among ourselves too?”

“He questioned my courage,” Connla whines.

“And you called him an old goat,” Conn retorts. “Now shake hands and forget it. We don’t have time for quarrels. Be men, not children.”

Goll sighs and extends a hand. Connla takes it, but his face is twisted and he shakes quickly, then returns to the small group of men who are always huddled close around him. As they leave, he starts to tell them again about the demon he speared and how he’s certain the blow was fatal, boasting of his great skill and courage.

→ Later. The gate of the rath is open. The cows and sheep have been led out to graze. Demons can only come at night, gods be thanked. If they could attack by day as well, we’d never be able to graze our animals or tend our crops.

I go for a walk. I like to get out of the ring fort when my duties allow, stretch my legs, breathe fresh air. I stroll to a small hill beyond the rath, from the top of which I’m able to look all the way across Sionan’s river to the taller hills on the far side. Many of the men have been to those hills, to hunt or fight. I’d love to climb the peaks and see what the world looks like from them. But it’s a journey of many days and nights. No chance of doing that while the demons are attacking. And for all we know, the demons will always be on the attack.

I feel lonely at times like these. Desperate. I wish Banba was here. She was more powerful than me and had the gift of prophecy. She died last winter, killed by a demon. Got too close to the fighting. Struck by a Fomorii with tusks instead of arms. It took her two nights and days to die. I haven’t learnt any new magic since then. I’ve worked on the spells that I know, to keep in shape, but it’s hard without a teacher. I make mistakes. I feel my magic getting weaker, when it should be growing every day.

“Where will it end, Banba?” I mutter, eyes on the distant hills. “Will the demons keep coming until they kill us all? Are they going to take over the world?”

Silence. A breeze stirs the branches of the nearby trees. I study the moving limbs, in case I can read a sign there. But it just seems to be an ordinary wind — not the Otherworldly voice of Banba.

After a while I bid farewell to the hills and return to the rath. There’s work to be done. The world might be going up in flames, but we have to carry on as normal. We can’t let the demons think they’ve got the beating of us. We dare not let them know how close we are to collapse.

→ After a quick meal of bread soaked in milk, I start on my regular chores. Weaving comes first today. I’m a skilled weaver. My small fingers dart like eels across the loom. I’m the fastest in the rath. My work isn’t the best, but it’s not bad.

Next I fetch honey from the hives. The bees were Banba’s. She brought them with her when she settled in the rath many years ago. They’re my responsibility now. I was scared of them when I was younger, but not any more.

Nectan returns from a fishing trip. He slaps two large trout down in front of me and tells me to clean them. Nectan’s a slave, captured abroad when he was a boy. Goll won him in a fight with another clan’s king. He’s as much a part of our rath now as anyone, a free man in all but name.

I enjoy cleaning fish. Some women hate it, because of the smell, but I don’t mind. Also, I like reading their guts for signs and omens, or secrets from my past. I haven’t divined anything from a fish’s insides yet but I live in hope.

The women grind wheat in stone querns, to make bread or porridge. Some work on the roofs of the huts, thatching and mending holes. I’d love to build a hut from scratch, draw a circle on the ground and raise it up level by level. There’s something magical about building. Banba told me that all unnatural things – clothes, huts, weapons – are the result of magic. Without magic, she said, men and woman would be animals, like all the other beasts.

Most of the men are sleeping, but a few are cleaning their blades and still discussing the night’s battle. It was one of our easier nights. The attack was short-lived and the demons were few in number. Some reckon that’s a sign that the Fomorii are dying out and returing to the Otherworld. But they’re dreamers. This war with the demons is a long way from over. I don’t need fish guts to tell me that!

Fiachna is working by himself, straightening crooked swords, fixing new handles to axes, sharpening knives. We’re the only clan in the tuath with a smith of its own. That was Goll’s doing when he was king. Most smiths wander from clan to clan, picking up work where they find it. Goll figured that if we paid a smith to settle, folk from nearby raths, cathairs and crannogs would come to us when their weapons and tools needed repairing, rather than wait for a smith to pass by. He was right. Our rath became an important focal point of the tuath — until the attacks began. The demons put paid to a lot of normal routines. Nobody travels now, unless it’s to flee the Fomorii.

When I get a chance, I walk over to where Fiachna is hammering away at a particularly stubborn blade. I watch him silently, playing with a lock of my short red hair, smiling shyly. I like Fiachna. He’s shorter than most men, and slim, which is odd for a smith. But he’s very skilled. Stronger than he looks. He swings heavy hammers and weapons with ease. If I could marry, I’d like to marry Fiachna. If nothing else, we’re suited in size. Maybe it’s because of the name Goll gave me, or perhaps it’s coincidence, but I’m one of the smallest girls in the rath.

But it’s not just his size. I like his kind nature and gentle face. He has a short beard – dark-blond, like his hair – which doesn’t hide his smile. Most of the men have beards so thick you can’t see their mouths, so you never know if they’re smiling or frowning.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.