Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

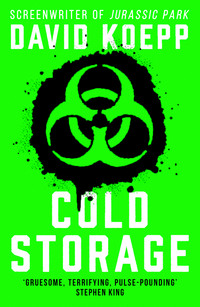

Kitabı oku: «Cold Storage», sayfa 3

Roberto looked around, understanding the town better now. Or the people, anyway. Jesus, the people, all of them.

Hero walked quickly to the tank and knelt down beside it, flipping open her sample case again. “The ant stops acting for itself. All it knows is it has to move. Up. It climbs the nearest stalk of grass, clamps its jaws down as hard as it can, and waits.”

“For what?” Trini asked.

“Until the fungus overfills the body cavity and it explodes.”

Roberto looked up at the roofs of the houses and shivered. “That’s why they climbed. To spread the fungus as far as they could.”

Hero nodded. “It’s a treeless wasteland. The roof was the highest spot they could find. You work with what you’ve got.” Her gloved hands picked carefully through the sharp metal tools in the case. She picked a flat-bladed instrument with a ring grip, slipped it over her right index finger, and flipped open a sample tube with her left hand. Carefully, she scraped as much of the fungus into the tube as she could. “It’s an extremely active parasitic growth, but that’s about all we’ll know until I can isolate the proteins with liquid chromatography and sequence its DNA.”

Roberto stared as she flipped the tube shut with a practiced gesture.

“You’re bringing it back?”

She looked up at him, not understanding. “What else am I supposed to do?”

“Leave it. We’ve got to burn this place.”

“Go right ahead,” she said. “But we need to take a sample with us.”

Trini looked at Roberto. “She’s right. You know she’s right. What’s the matter with you?”

Roberto didn’t get scared very often, but suddenly he was thinking about his little boy and about the possibility that he might never see him again. He’d heard having a kid could do that to you, make you tentative, aware that you served some purpose larger than yourself. To hell with the rest of the world, I make my own people now, and I have to protect them. Nothing else mattered.

And then there was Annie. I have a wife, a woman I love completely whom I was this close to betraying, and I would like very much to get back and get a head start on making that up to her, for the rest of our lives. That’s what was the matter with him, that’s what he was thinking, but he said none of it.

Instead, he said, “For Christ’s sake, Trini, it has an R1 rate of 1:1. Everyone who came in contact with it is dead, every single person. The secondary attack rate is a hundred percent, the generation time is immediate, and the incubation rate is … we don’t know, but less than twenty-four hours, that’s for goddamn sure. You want to bring that back into civilization? We’ve never seen a bioweapon with anything remotely close to this kind of lethality.”

“Which is exactly why it has to be tanked and studied. C’mon, man, you know that. This place won’t stay a secret, and if we don’t bring it back, somebody else’ll come get it. Maybe somebody who works for the other side.”

It was a valid debate, and while they carried on with it, the corrosive inside Hero’s boot heel continued to work with single-minded purpose. The fluoroantimonic acid had proven to be just the thing for eating through hard-soled rubber, but it wasn’t so much digging a hole as changing the chemical composition of the boot itself as it went along. Minor mutations occurred almost in a spirit of experimentation as the strength of the boot’s chemical bonds varied. The substance was a nifty adapter, zipping through most of the benzene group till it found the exact compound it was looking for. Finally, it reached the other side of the sole, evolving out onto the surface of the inner boot, just beneath the arch of Hero’s right foot. Benzene-X—it had hybridized so many times at this point that it defied classification according to current known chemical compounds—had opened a door for the fungus, which was so much larger in molecular size, to pass through to the interior of Hero’s suit.

Which is where Cordyceps novus found nirvana. The boot, like the rest of the hazmat suit, was loose-fitting, designed to encourage air circulation to prevent the wearer from overheating. The breathing apparatus contained a small fan for oxygen recirculation, which meant a fresh supply of O2 was continually moving through the inside of the suit. Strands of grateful fungus spun off into whispery tendrils and went airborne, drifting upward on a rising column of warm CO2, until they landed lightly on the bare skin of Hero’s right leg.

Still unaware of the enemy invasion going on inside her suit, Hero screwed the top onto the sample tube, broke a seal on its side, and the tube hissed, a tiny pellet of nitrogen flash-freezing it until it could be reopened in a lab and stored permanently in liquid nitrogen. She dropped the tube back into the foam-padded slot in the case, clicked it shut, and stood up. “Done.”

The debate over what to do next had been resolved the way it always was, which is to say that Trini prevailed. She heard Roberto’s arguments, let them go a little bit past the point she felt was necessary, given the difference in their ranks, then looked directly at her friend, lowered her voice a tone or two, and said just one word.

“Major.”

The conversation was over. Trini was the officer in charge, and the advice of the scientific escort was on her side. The outcome had never been in doubt, but Roberto had felt a humanitarian urge to object anyway. What if, just this once, they did what was obvious and right, even if it was directly contrary to procedure? What if?

But they’d never find out, and in the end, Roberto settled on a secondary assurance: they would take one sample, one, carefully sealed in the biohazard tube, and would not leave Western Australia until the two respective governments had agreed to drop an overkill load of oil-based incendiary bombs on the place. Anything would suffice, even old M69s or M47s loaded with white phosphorous would do the job. There was nothing left to save here anyway.

They left town and walked back toward the jeep.

Four

Inside Hero’s suit, Cordyceps novus found what it had been looking for: a tiny scratch in the surface of Hero’s calf. Even an overwide pore opening would have been big enough for it to gain entry into her bloodstream, but the open scratch, which cut through two layers of her skin, fairly yawned with possibility.

Hero didn’t even know she had an open wound. It had been an absent-minded scratch; she was reacting to an itch produced by a changed cleaning product—the hotel that washed her jeans last week had used a cheap optical brightener with a higher concentration of bleach than she was used to. So it itched. And she scratched. And the fungus entered her bloodstream.

“What’s that smell?” Hero asked. They were fifty yards from the jeep.

Roberto looked at her. “What smell?”

She sniffed again. “Burnt toast.”

Trini shrugged. “Can’t smell anything.” She looked back, glad to leave the town behind. “This whole place is gonna smell like burnt toast by the end of the day.”

But Roberto was confused, still looking at Hero. “In your suit?”

Hero held up an arm and regarded it, as if reminding herself she was wearing a sealed biohazard suit. “That doesn’t make sense, does it?”

In fact, it made perfect sense. Cordyceps novus was really warming up and had superheated the starches and proteins just inside Hero’s epidermis. As a by-product of the reaction, they outgassed acrylamide, producing the same smell as burnt toast. It was generating heat as well, and the sudden rise in temperature on Hero’s skin would surely bother her soon. But the fungus was attentive to that possibility and was moving fast through her bloodstream, racing to get to her brain, where it would intercept the messages from her pain receptors. This in itself was no great trick—a tick does the same thing, releasing a surface anesthetic as soon as it burrows into its victim’s skin so its bloodsucking can go unnoticed for as long as possible. But the fungus had a long way to travel and a lot of receptors to block. Hero’s heartbeat accelerated, which circulated her blood faster, inadvertently helping her would-be killer.

She stopped walking. “There can’t be a smell in my suit, it’s sealed and overpressured. There’s nothing in here but oxygen and clean CO2. Why is there a smell in my suit?”

She was starting to panic. Trini tried to defuse it. “There are probably a lot of jokes I could make here—”

“It’s not fucking funny,” Hero snapped.

“It’s not, Trini, shut the hell up. Something penetrated her suit.”

“That’s not possible,” Hero said, to convince herself as much as anyone else.

“Just keep moving,” Trini advised. “We’ll lose the suits at the jeep. We can’t take them out of here anyway, they need to burn. We’ll check yours for breaches.” She looked at Hero, her manner serious. “Do you feel anything?”

Hero thought. “No.”

Roberto persisted. “Take a minute. Focus on each part of your body. Anything different at all?”

Hero’s breathing steadied. She considered the question, going through her anatomy from the bottoms of her feet to the top of her head. “No. Nothing different.”

Inside her body, it was a different story. The fungus had penetrated Hero’s brain and was reproducing at nightmare speed, seeking out and blocking her nociceptors the way an invading army shuts down the internet and television stations. There was a red alert blaring in Hero’s brain, flags were waving, alarm bells ringing, but the ends of her sensory neurons’ axons had been taken over and blocked from responding to damaging stimuli. They could no longer send potential threat messages to her thalamus and subcortical areas. They were screaming into a void.

Hero Martins was dying, but the neural message she got from her brain was that everything was fine, just fine, don’t worry about a thing.

“I’m okay.”

“You’re sure?” Roberto asked.

She nodded. “Let’s just get out of here.”

They started walking again, now forty yards from the jeep. Hero’s brain thought through possible reasons a foreign smell should have presented itself inside her suit. Nothing believable came to mind. She decided she would not destroy this suit; she was going to tank and return it, she wanted to have a chance to take it apart and look at every inch of it in case there was a tear or foreign substance inside, in which case somebody in PPE was going to get an earful about procedure.

The jeep was now thirty yards away. Hero felt light-headed and realized she hadn’t eaten since nine or ten hours ago. Then again, looking at Uncle’s mutilated corpse wouldn’t exactly stimulate anyone’s appetite, so there was no reason to think anything unusual about that. She ran through her physical inventory once again, but other than an elevated heart rate and some quickened breathing, there wasn’t anything physically different about her that she could detect. She squinted up at the sun, and as she did a thought floated through her mind.

except there’s no telephone service out here

Well, no, there wasn’t. What did that matter? She looked down at the case in her hand, thinking about what she had inside the tube. People were going to lose their minds over this one. She wondered if the CDC would even accept it.

so there’s no telephone poles

She shook her head to clear it and resumed her train of thought. There were only a handful of labs in the Western Hemisphere that were set up to store biosafety level 4 pathogens, and Atlanta and Galveston would reject it outright, improperly classifying it as extraterrestrial because of its trip outside Earth’s atmosphere.

maybe an electrical tower

The U.S. Army would fight for it, no question about that, but Fort Detrick had suffered a breach eighteen months ago and no one was eager to—

they’ve gotta have power right don’t they have power?

She snapped her head to the side, Come on, focus. They were ten yards from the jeep. Her image of it suddenly shuddered and divided into sixteen identical rectangular boxes, sixteen images of the jeep, neatly separated and replicated. Hero felt her skin go cold because that wasn’t something you could easily ignore or pass off to hunger or exhaustion, but then again, she thought, I used to faint when I was a kid, in school assemblies sometimes, and didn’t it feel like this?, wasn’t there a prickling in her scalp and then her vision would go weird and she’d see double right before she keeled over sure that was probably it low blood sugar or

a radio tower, fifty kilometers back, didn’t I see something, wasn’t it a radio tower?

The image swam through her mind, crisp and clear: they had driven past a radio tower in the middle of the desert, just alongside the road, about a hundred meters high, with a small black utility box at the base of it.

“That’s exactly what it was.”

She’d said that last bit out loud, and Roberto and Trini turned and looked at her.

“What?” Roberto asked.

She looked at him. “Huh?”

“That’s exactly what what was?”

Hero had no idea what he was talking about. Was it possible that Roberto had somehow become infected by the fungus, that it was his suit that had malfunctioned, and that he was starting to lose his mind? She certainly hoped not, he was a nice enough guy, even if he was a total flirt, she really had to lay off the married men, never again, she vowed, right there and then, from now on either find someone appropriate or be content with

It can’t be that hard to climb.

Oh, shit. She had to think this through.

To climb. The radio tower. It had lateral struts about four or five feet apart, but there’s probably a service ladder inside the structure, how else would they repair anything that broke near the top of the thing? I could climb that.

For the last time, the weight and pressure of the healthy, functioning neurons in Hero’s brain outweighed those that had been consumed, destroyed, or shut down by Cordyceps novus. Her prefrontal cortex, which handled reasoning and sophisticated interpersonal thinking skills, reasserted itself in a burst of clarity and control, and told her quite clearly that based on:

1 her disordered thought processes;

2 the smell of burnt toast inside her suit that indicated a foreign contaminant;

3 the expressions on the faces of Trini and Roberto, who clearly thought something was wrong with her; and

4 her sudden and irrational fixation on the feasibility of climbing a fucking radio tower, for Christ’s sake, she had likely been infected by the fungus and was moments away from coming under the control of a rapidly replicating fungus that constituted an extinction-level threat to the human race.

Still walking, she glanced to her right and saw Trini was carrying her handgun loosely at her side as she and Roberto looked back and forth from her to each other, trying to communicate their concern wordlessly rather than over the radio system, which she would be able to hear.

Take the jeep and drive to the tower.

Hero walked faster, headed for the jeep. They let her, happy to fall behind so they could keep an eye on her.

Climb the tower.

As Hero neared the jeep, she saw the keys, the sunlight shining off them in the ignition. She felt pulled toward them.

Climb the tower.

Hero’s frontal lobe was in a doomed fight for control. It made up a third of the total volume of her brain, but was now overrun with a florid, healthy colony of Cordyceps novus. Her flag of intellectual independence fell. Still, her conscious thought didn’t give up; it merely darted away, blew through the wasteland of her already conquered temporal lobe, and turned in desperation to the last part of her mental apparatus that was still free—her parietal lobe. There, her thought stream was precariously her own, but severely limited.

just math now, math and analytics, where X = regeneration of healthy brain tissue probability is zero-X, try recovery rate, recovery rate in event of default

She was pulling up a freshman economics class now, but it was the only scrap of useful knowledge left kicking around unfettered in her head, the only avenue of reasoning left open to her, and it was going to have to do. So, let’s try a calculation, shall we? The equation to be formed would need to answer only one question: Could she survive this?

recovery probability versus loss given default (RP < or > LGD) dependent on instrument type (where IT = hypereffective mutating fungus), corporate issues (where CI = major default of more than 50 percent of healthy brain tissue), and prevailing macroeconomic conditions (where PMCs = every single other person who ever encountered this thing is dead), so RP = IT/CI × PMC = there is no fucking chance whatsoever.

The answer was no. She could not recover. She was going to die. The only question was how many people she was going to take with her when she did.

CLIMB THE TOWER, her brain told her.

And with the tiny bit of volition Dr. Hero Martins still had left, she replied.

NO, she said.

She turned around, fast. Trini didn’t have time to react, in part because she was too stunned by the sight of Hero’s swollen, heaving face, which was distended and discolored, the skin stretched so tight it was cracking. Hero was on her before Trini knew what was happening. She wrenched the gun from Trini’s hand—

“Gun out!” Trini shouted, but Roberto had already seen it. He yelled at Hero to stop, but she was backing away from them already, backing away and turning the gun around on herself. She reached up with her left hand and ripped her suit’s Velcro flap over the zippered O2 access port, tore that open, shoved the gun inside the suit, sealed the Velcro flap around the barrel, pressed the barrel of the gun up against her chest—

“Don’t!” Roberto yelled, knowing it was too late even as he said it.

Hero pulled the trigger.

The bullet broke her skin and crashed through her breastbone, tearing open a hole in her chest the size of a quarter. Like a balloon popped by a pin, the rest of her went all at once, bursting at the sudden release of pressure. All Trini and Roberto saw was her head, which in one moment was a disfigured, although recognizable, human head, and the next moment was a wash of green gunk that completely covered the inside of her faceplate.

Hero fell, dead.

But she’d kept her suit intact.

LESS THAN SEVENTY-TWO HOURS LATER, TRINI AND ROBERTO WERE IN the car, just over three miles away from the Atchison mines, their eyes glued to the box in the back of the truck just ahead of them. Hero’s field case had been packed, unopened, into a larger sealed crate filled with dry ice.

So far things had gone smoothly. Gordon Gray, the head of the DTRA, had taken Trini and Roberto exactly at their word, because they were the best, and he ordered their explicit instructions be followed to the letter. When Gordon Gray gave an order, people followed it, and since all the residents of the town were dead and the land itself held no value, there was no one and no reason to object. The firebombing of Kiwirrkurra was agreed to without debate by the respective governments. The unlucky place burned, and with it every molecule of Cordyceps novus, except for the sample in Hero’s biotube.

The question of what to do with the tube was tougher to answer. As Hero had speculated, the CDC wanted no part of storing something that had been born, or at any rate partially bred, in outer space. Though the Defense Department was willing, its only suitable facility was Fort Detrick, which was out of the question. The breach there eighteen months earlier had triggered a top-down review that was only now entering its second stage, and the idea of cutting short a safety analysis in order to store an unknown growth of unprecedented lethality was not met with enthusiasm.

Atchison was Trini’s idea. She’d worked with the National Nuclear Safety Administration in the early ’80s on weapons dismantlement and disposition readiness, as the idea of nuclear disarmament became politically palatable under the Reagan administration’s INF Treaty initiative. Sub-level 4 of the Atchison mine facility had been conceived and dug out as an alternative to the Pantex Plant and the Y-12 National Security Complex, disposal centers that were at capacity already, dealing with outmoded fission devices from the late ’40s and early ’50s. But as INF negotiations dragged on it became clear that Reagan’s strategy was really to get the other guy to disarm, and Atchison’s lowest sub-level sat empty and secure, never to be used.

The location was ideal for their needs. Because the mines were uniquely situated over a second-magnitude underground cold spring that pushed near-freezing water up from the bedrock at 2,800 liters per second, the lowest subterranean level at Atchison never rose above 38 degrees Fahrenheit. Even in the unlikely event of an extended power outage, the temperature at which the fungus would be stored was guaranteed to remain stable, keeping it in a perpetual low-or no-growth environment, even if it somehow broke free of its containment tube. It was a perfect plan. Cordyceps novus was thus given a home, sealed inside a biotube three hundred feet underground in a sub-basement that didn’t officially exist.

AS TIME WENT BY, FEWER AND FEWER PEOPLE AT DTRA CAME TO SHARE Trini and Roberto’s alarmist view of the destructive capabilities of Cordyceps novus. How could they? They hadn’t seen it. There were no photographic records. The remote town had been incinerated, and the only remaining sample of the fungus was locked away, out of sight and out of mind. People forgot. People moved on.

Sixteen years later, in 2003, the DTRA decided the mine complex was a Cold War relic that could be dispensed with. The place was cleared out, cleaned up, given a coat of paint, and sold to Smart Warehousing for private use. The self-storage giant threw up some drywall, bought 650 locking overhead garage doors from Hörmann, and opened it up to the public. Fifteen thousand boxes of useless crap were thus given a clean, dry, and permanent underground home. That thirty-year-old drum kit that you never played could now survive a nuclear war.

The storage plan for Cordyceps novus was a perfect one.

Unless, that is, Gordon Gray took early retirement.

And his successor decided sub-level 4 was better off sealed up and forgotten.

And the temperature of the planet rose.

But how likely was any of that?