Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

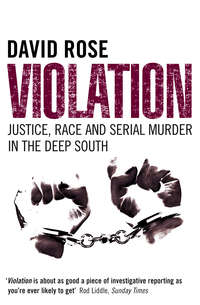

Kitabı oku: «Violation: Justice, Race and Serial Murder in the Deep South», sayfa 3

‘How much is it?’ I asked.

‘I can’t tell you that. But you know, most of the members are old families, and although newcomers are very welcome, there is a distinction. There is one guy who worked his way up from selling insurance. And although he’s seventy now, he’s still a newcomer. So maybe they sense that. You know what I mean?’

The joining fee, I discovered later that day, was $7,500. On her veranda that same evening, I described the club to my African-American friend Vicky Williams, and mentioned Elizabeth’s closing remarks. Vicky laughed, surprised at the way some people chose to spend their money, then came up with an alternative hypothesis. Mrs Senne, of course, was an employee: she could not be held responsible for following the club’s policies. But Vicky said, with a bitter little shrug, ‘It’s like, you’re a reporter, and you’re good at getting people to tell you their stories, and maybe you can tell when they’re lying. That’s how it is as a black person, when you encounter racism. People can seem ever so nice, but sometimes, you can smell it.’

TWO We’ve Got a Maniac

The black fiend who lays unholy and lustful hands on a white woman in the state of Georgia shall surely die!

REBECCA FELTON (1897)

Hours after nightfall, when the last lights are going out and the only sound is the rustle of the pines and sweetgums on the balmy Georgia wind, the terror that enveloped Wynnton seems closer, more palpable. I’d planned to take a slow drive, to pause and stare at these moon-shadowed dwellings as once the killer saw them, in the moments before he pounced. My guide, a local architectural historian, kept hurrying me on. ‘People here might not like it if we dawdle,’ she said. ‘You don’t want to have to explain yourself to the police. Besides, a lot of people here have guns.’

If one knew nothing of its history, Wynnton after dark might feel no different from any American neighbourhood. But knowledge cannot be undone, and despite myself I shared her unease. I had seen the crime scene photographs, and the passage of more than two decades had done nothing to diminish their horror. It wasn’t just the bodies, their swollen faces seeming to betray a heart-rending mix of fear and resignation. What conveyed the sense of violation most was the ordinariness of their surroundings.

Inside the houses we were driving past, policemen’s cameras had captured life’s final debris. In one home, the story of a death struggle was told by large-print books, some still stacked neatly on their shelves, others strewn across a patterned carpet; in another, the floor was covered with an old lady’s intimate garments, ripped from closets, then used by the killer to fashion his weapon. Most poignant of all were the family photographs, still on their tables and dressers. Amid this everyday banality lay the victims: twisted, bruised, exposed.

The horror began to surface at 10 a.m. on Friday, 16 September 1977. Dixon Olive worked in the city’s public health department and had been fretting indecisively for more than an hour. Mary ‘Ferne’ Jackson, his boss and colleague, had failed to show up for work. She was a woman of meticulous and unchanging routine, and Olive had already spoken to Ferne’s best friend, Lucy Mangham. Early the previous evening, Lucy said, she had picked up Ferne from her red-brick bungalow on Seventeenth Street in Wynnton, and they had gone together to what Lucy called ‘an enrichment school’ at St Luke’s United Methodist Church on Second Avenue, a spacious neo-Georgian edifice. Afterwards, Lucy took Ferne directly home, and waited by the kerb while she unlocked her door. She had noticed, she told Olive, that Ferne’s bronze-coloured Mercury Montego was parked in its usual space outside. Lucy was away to her own house, only a street away, by 9.45 p.m. Having spoken to her, Olive decided to phone the police.

Mrs Jackson, who was fifty-nine, had been Columbus’s Director of Public Health Education for twenty-six years. A widow, she had no children, and in her head-and-shoulders portrait she looks a little austere, as if the years of giving lectures on the dangers of smoking or the need for a healthy diet had begun to weary her. But she was much admired. She was about to be named Public Health Educator of the Year by the American Public Health Association. Her nephew, Harry Jackson, a successful businessman, was planning to run for Mayor.

When Jesse Thornton, the first police officer to respond to Dixon Olive’s call, arrived at Ferne Jackson’s house, he could see no sign that anyone had forced an entry. The doors were locked, the windows unbroken, and had he not been alerted by Mr Olive and some of Ferne’s neighbours, he would have been tempted to leave. But her car, they pointed out, was missing. Thornton spoke by radio to his patrol commander, who advised him to get inside the house and look around. He used the knife he always carried to remove the mesh insect screen from the living-room window, and to jiggle the lock until he could get it open.

Many years later, Thornton would tell a murder trial jury what he did next. The first space he came to was the hallway, and straight away, ‘I could see something that wasn’t right.’ Ferne’s approach to tidiness was as meticulous as her time-keeping. But in the hall, said Thornton, ‘There was stuff laying on the floor, papers, articles, just scattered all over the floor. There was a pillow on the floor, there was a suitcase that was opened, the drawers had been opened on the dresser, and stuff was pulled out and hanging out of it.’ He continued, very slowly, down the passage towards Ferne Jackson’s bedroom, his hand poised over his weapon. ‘Once I got to the bedroom, I looked inside,’ Thornton said. ‘That’s when I saw the body on the bed.’

Ferne’s sheets had been pulled up round her head, and her nightgown tugged upwards, in order to expose her hips, pubic area and waist. Thornton could see there was blood on the sheets.

It fell to the Columbus medical examiner, Dr Joe Webber, to conduct a post mortem. The killer, he wrote in his subsequent report, had tied a nylon stocking and a dressing-gown cord together to make a single ligature, which was wrapped around Mrs Jackson’s neck three times, leaving three ‘very deep crevasses’. There was a large area of haemorrhage and bruising on the left side of her face and head, so that the white of her left eye was ‘almost obliterated’ by bleeding; the result, he believed, of a massive blow to her head. The white of her right eye was a mass of tiny, pinpoint petechial haemorrhages where her blood, deprived of oxygen, had burst from its vessels close to the surface, a common sign of strangulation. The small hyoid bone at the front of the throat was fractured, and there was more bleeding inside her neck. Her brain was swollen, another symptom associated with an interruption to the blood supply. Her sternum, or breastbone, had been fractured, an act which would have required the application of enormous force: ‘It apparently had been flexed and pressure applied to the point that the bone snapped about midway between the upper and lower ends.’ Finally, her vagina was bloodied, torn and bruised. Although Dr Webber could not find spermatozoa, he felt it would be reasonable to conclude that Ferne Jackson had been raped. Later, traces of seminal fluid would be found on her sheet.

There was no obvious motive for Ferne’s murder. Despite ransacking her house, the killer had left her jewellery and other valuables untouched. She was still wearing two diamond rings. Nor did she have any enemies, and her popularity as a selfless public servant made her death all the harder to bear. ‘She was one of the unsung heroes who quietly, gently and persistently worked for the betterment of her community,’ Dr Mary Schley, a local paediatrician, told the Columbus Ledger. ‘Ferne Jackson fought for the underprivileged, the minority groups, and against poverty and for better mental health,’ added A.J. Kravtin, one of many readers who wrote to the paper after she died. While no one knew who was responsible, ‘if it turns out to be one of the above, they killed the wrong person. They killed a friend.’

Three days after the discovery of her body, the Ledger published an editorial in her memory. ‘It’s always tragic when an innocent person becomes the victim of a violent crime,’ it began, somewhat prosaically. ‘It’s even more tragic when the victim is someone who has devoted his or her life to helping others.’ What could be done about the kind of crime that had taken Mrs Jackson’s life, the paper asked, and how could further such acts be prevented? Increased police patrols would help. ‘Vigorous efforts to apprehend the assailant and assure him a swift trial and appropriate punishment, if found guilty, might deter others from committing similar crimes … Greater emphasis on respect for law and expanded educational and job opportunities might get at some of the underlying factors.’ It was not to be that simple.

Ferne Jackson was murdered barely a month after the capture of David Berkowitz, the sexually driven ‘Son of Sam’ who killed or seriously injured a dozen women in New York. Partly in response to Berkowitz’s bloody but compulsive career, Robert Ressler, the founder of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit at Quantico, Virginia, had coined a new term to describe the perpetrators of such actions – they were, he suggested, ‘serial killers’. The phrase had swiftly gained widespread currency. It took just eight days after the murder of Mrs Jackson for it to become apparent that one was at large in Columbus.

Jean Dimenstein was seventy-one, a wealthy spinster from Philadelphia who owned and ran a small department store, Fred and Jean’s, with her brother. She spent the evening of 24 September with two friends at a steakhouse on Macon Road. They drove her home a little before 10 p.m., and watched from the car as she let herself into her house on Twenty-First Street, about half a mile from the residence of Mrs Jackson. As usual, she used the door at the side of the house, which led into her kitchen from her carport. Some time later that night, working in absolute silence, the killer removed the pins from the door’s hinges, laid them to one side and entered Miss Dimenstein’s house. Her sister-in-law, Francine, arrived there for coffee at ten the following morning. She noticed at once that Jean’s car was missing, saw the open doorway, and called the police.

Like Ferne Jackson, Jean Dimenstein had been beaten about the head, strangled with a ligature made from a stocking wrapped around her neck three times, and raped. She was wearing the two diamond rings and, beneath the ligature, the diamond necklace she had worn the previous night. Although her house was also ransacked, it appeared that again, nothing had been stolen. To the chagrin of the police, who were cautiously claiming that they couldn’t be sure that Jackson and Dimenstein had been killed by the same assailant, J. Donald Kilgore, Columbus’s coroner, told the Ledger of the similarities between the two murders. He was, he said, quite certain that there was only one Columbus strangler. As if the bubbling panic that began to seize the city needed further encouragement, Kilgore informed journalists of supposed details that were not borne out by later investigations: that ‘some sort of inflexible object was used to violate the women’, and that ‘a pillow was used to muffle their horrified screams while [they were] being tortured sexually before their death’. The motive for the crimes, he proclaimed, was torture.

In the autumn of 1977, Kilgore had been in his post for a year. He was not, however, a qualified forensic scientist, nor a pathologist, but the former director of a funeral home who had been embalming bodies with unusual enthusiasm since his teens. ‘By the time I was twenty-one, I had participated with embalming 1,500 bodies,’ he once told a Columbus reporter. ‘You’ve got to disassociate yourself from the body at such times, even if the body has been mutilated. You try to associate with something positive. For instance, I don’t see blood. I see ketchup.’ Kilgore said that ‘I treat every person’s body with respect. I always have.’ But as time went on, growing numbers of police officers came to disagree, accusing him of ‘aggressive investigation and handling of the remains’ at murder scenes. Some filed official complaints. In 1989, the tension between Kilgore and the Columbus Police Department (CPD) reached a new peak when he was accused of and investigated for allegedly decapitating a suicide victim. Under Georgia law, only a qualified medical examiner could cut into a body during a post mortem, and Kilgore was forced to admit that he often did so before such a person arrived. However, he insisted that he had not removed the victim’s head. He had merely ‘performed a procedure that involved the opening of the top portion of the skull’.

Told of Jean Dimenstein’s murder while he was attending Sunday worship, Columbus’s Mayor, Jack Mickle, addressed reporters on her lawn, ringed by ten police cars. ‘We’ve got a maniac,’ he said. ‘I hope we get this guy. We gotta get this guy.’

The police had not been slow to notice that the cars belonging to both of the victims were found abandoned in Carver Heights, a black district on the southern side of Macon Road. Having examined the crime scenes and bodies, Donald Kilgore supported the CPD’s growing suspicion that the strangler was black. Later, he told reporters he had looked under the microscope at pubic hairs left at the crime scenes, and in his view, being black and curly, they displayed ‘Negroid characteristics’. In the Deep South of the United States, this was not an incidental matter.

In 1941 the Southern writer Wilbur J. Cash diagnosed what he termed the ‘Southern rape complex’, a social neurosis that originated long before the Civil War, and that continued to dominate whites’ approach to race relations for many decades afterwards. In the collective mind of the South, Cash argued, white women’s status was exalted to a bizarre and extraordinary degree, while their virtue was seen as at constant risk from the marauding, violating power of black sexuality. In part, he suggested, this was the product of guilt on the part of white male slave-owners at their own numerous illicit relationships with slave women, who often gave birth to mixed-race, light-skinned children. Soiled and shamed by their own desires and their inability to restrain them, white men projected an image of pristine chastity onto their wives and daughters, while assuming that black males must inevitably share their own lust for erotic miscegenation. By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, writes Cash, ‘she was the South’s Palladium, the Southern woman – the shield-bearing Athena gleaming whitely in the clouds, the standard for its rallying, the mystic symbol of the nationality in the face of the foe … Merely to mention her was to send strong men into tears – or shouts.’

Columbus shared this dangerous fantasy. It could be found in purest form at the climax of Mrs Chas. Williams’s 1866 appeal on behalf of the city’s Soldiers’ Aid Society to newspapers and other kindred spirits that heralded the start of Confederate Memorial Day. In rousing, heartfelt language, Mrs Williams had claimed that the need to safeguard white female honour provided the noblest justification of all for the deaths of so many Southern men in pursuit of the doomed Lost Cause:

The proud banner under which they rallied in defence of the holiest and noblest cause for which heroes fought, or trusting woman prayed, has been furled forever. The country for which they suffered and died has now no name or place among the nations of the earth. Legislative enactments may not be made to do honour to their memories, but the veriest radical that ever traced his genealogy back to the Mayflower could not refuse thus the simple privilege of paying honour to those who died defending the life, honour and happiness of the Southern women.

After the South’s defeat, the slaves’ emancipation posed a new and terrible threat. Before the war, men such as Georgia’s Governor Brown had warned that if the slaves were freed, they would soon be asking for white women’s hands in marriage. Now that day had come to pass. In the summer of 1865, writes Nancy Telfair in her history of Columbus, ‘white women could not go alone on the streets’. The reason was that they were filled by black former slaves. As W.J. Cash put it, by ‘destroying the rigid fixity of the black at the bottom of the scale, in throwing open to him at least the legal opportunity to advance’, the abolition of slavery opened up a fearful vista in the mind of every Southerner. A war had been fought and lost to preserve white female honour. Though defeated, the white Southern male must fight still harder to protect it in time of peace. ‘Such,’ writes Cash, ‘is the explanation of the fact that from the beginning, they justified – and sincerely justified – violence towards the Negro as demanded in defence of women.’

Cash, of course, was white. African-Americans had noticed the effects of this rape complex long before his book was published in 1941. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the black activist writers Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. du Bois revealed how spurious rape allegations were used time and again by Southern whites to justify the wave of lynching, then at its terrible peak. Du Bois began his campaign when he investigated the torture and killing of Sam Hose in 1897 near Newnan, Georgia, a small farming town between Atlanta and Columbus. Hose, a farm labourer, had killed his employer, Alfred Crawford, in the course of a fight that started when he complained that he had not been paid his wages. When Hose disappeared, the local newspapers claimed he had also raped Crawford’s wife, Mattie, described before her marriage as ‘one of the belles of Newnan’. As vigilantes mounted a state-wide manhunt, the Newnan Herald and Advertiser warned the authorities not to interfere with the summary justice that must surely follow. Hose, it said, must be ‘made to suffer the torments of the damned in expiation of his hellish crime’, to demonstrate to all ‘that there is protection in Georgia for women and children’.

After his arrest near Marshallville, seventy-five miles to the south-east, Hose was transported to Newnan, where his death was deliberately delayed in order to magnify its spectacle. In front of a crowd of four thousand, many of whom had arrived aboard special trains from Atlanta, the mob slowly tortured him by slicing off his ears, nose, fingers and genitals, then burnt him at the stake. Already covered in blood, he was heard to cry ‘Sweet Jesus’ as the smoke entered his nose, eyes and mouth, and the flames roasted his legs; in a final, desperate struggle to break the chain which bound his chest, he burst a blood vessel in his neck.

Although an attempt had been made to get Mattie Crawford to identify Hose as her supposed rapist, she did not do so, and it seems improbable that she was raped at all. Du Bois commented: ‘Everyone that read the facts of the case knew perfectly well what had happened. The man wouldn’t pay him, so they got into a fight, and the man got killed – then, in order to rouse the neighbourhood to find this man, they brought in the charge of rape.’

The orator and writer Frederick Douglass, a former slave and arguably the greatest chronicler of the black experience of Emancipation and its aftermath, saw how the effects of bogus rape claims spread far beyond the places and people they directly involved. In the last speech of his life, delivered in Washington in January 1894, he argued that white propaganda about rape by blacks had become a device to justify their continued subjugation. ‘A white man has but to blacken his face and commit a crime, to have some negro lynched in his stead. An abandoned woman has only to start the cry that she has been insulted by a black man, to have him arrested and summarily murdered by the mob.’ Douglass quoted the recent words of Frances Willard, leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union: ‘The coloured race multiplies like locusts in Egypt. The safety of women, of childhood, of the home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof tree.’

The truth, Douglass pointed out, was that when most of the South’s white men had been away at the war, their women went unmolested. There was simply no substance to this ‘horrible and hell-black charge of rape as the peculiar crime of the coloured people of the South’. But its unchallenged prevalence in white society had terrible consequences, not only for the victims of lynch mobs but for black people as a whole: ‘This charge … is not merely against the individual culprit, as would be the case with an individual culprit of any other race, but it is in large measure a charge against the coloured race as such. It throws over every coloured man a mantle of odium.’ It underpinned the exclusion of blacks from politics and the right to vote, and the racial segregation of the so-called ‘Jim Crow’ laws then being enforced throughout the South. The fear of rape had become the ‘justification for Southern barbarism’. Douglass ended by quoting the former Senator, John T. Ingalls. There need be no ‘Negro problem’, he said. ‘Let the nation try justice, and the problem will be solved.’

Another perspective emerges from Portrait in Georgia, a short and terrifying stanza by the black writer of the 1920s, Jean Toomer, in which he casts his erotic attraction for a white woman in the light of its likely consequence should his desire be fulfilled:

Hair – braided chestnut

Coiled like a lyncher’s rope

Eyes – faggots

Lips – old scars, or the first red blisters,

Breath – the last sweet scent of cane,

And her slim body, white as the ash

Of black flesh after flame.

The Southern rape complex could manifest itself with startling power when grounded in baseless fantasy. But even before Ferne Jackson’s murder, in the Columbus of the late 1970s, it was beginning to seem as if its racist account of African-American sexuality was a simple description of fact. On 30 November 1976 Katharina Wright, the nineteen-year-old bride of a military officer, who had lived in Columbus for only a fortnight, was raped, robbed and murdered by a man who entered her house on Broadway by posing as a gas company employee. The killer stole $480 in cash, and was said to have shot her as he left. The following September, just before the first stocking strangling, a mentally retarded black man named Johnny Lee Gates was convicted and sentenced to death for these crimes. (After many legal vicissitudes, his sentence was commuted to life without parole in 2003.)

Katharina Wright was German, and although the case attracted its share of news coverage, its impact was limited. Much more shocking to white Columbus was the killing of Jeannine Galloway on 15 July 1977, two months before the death of Ferne Jackson. In Galloway’s brutal slaying, it seemed that whites’ primordial fears had achieved realisation.

Galloway, aged twenty-three, was a blonde and beautiful virgin who still lived with her parents, and who devoted much of her leisure time to directing the choir at the St Mary’s Road United Methodist Church. A talented musician, she played the piano, organ, clarinet, saxophone and guitar, and was as happy playing jazz as Christian hymns. Her fiancé, Bobby Murray, met her when they were both students at the Columbus College music school. Before enrolling, he’d been on the road with a rock band; after taking advice from one of her friends, he cut his hair and shaved his beard in order to impress Jeannine. On trips with the college jazz big band, other musicians ‘would sneak a beer or smoke marijuana’, Bobby told the Ledger. ‘Partaking of neither, Jeannine would still be in the middle of the action. Somebody would say, “Have a drink. Have fun.” She’d get real quiet and tell them right quick, “I am having fun.” She got high on life.’

For years after her murder, the Columbus newspapers continued to run long feature articles about her, on significant anniversaries of her passing, or when some development occurred in the case of her killer, a young African-American criminal named William Anthony Brooks. In these memorials, her qualities came to be described as belonging more to heaven than earth. ‘She was just an angel, a bright and shining light who was just every father’s dream,’ her church’s Reverend Eric Sizemore told reporters after one legal milestone in 1983.

There is no way to mitigate the horror of her murder. Early in the morning of her death, Jeannine was putting out the garbage, chatting to her mother, who stayed inside the house. She bent down to leave the bin, then straightened and came face to face with William Anthony Brooks, a young African-American. He was holding a loaded pistol, which he used to force her into her own car and drive to an area of marshy wasteland behind a school two miles away.

‘She was continually asking me to let her go – to take her money and the car and let her go,’ Brooks told the police after his arrest, a month later, in Atlanta. Instead, he marched her into a wood: ‘I told her to take her clothes off and she said no, and I yelled at her to take her clothes off.’ After raping her, Brooks’s statement continued, he asked if this had been the first time that she had had sex. ‘She said yes, and I said I didn’t believe it. She started screaming and wouldn’t stop and I pulled out my gun so she’d know I was serious … she kept screaming and the pistol went off. She kept trying to scream but she couldn’t get her voice.’ Jeannine died slowly, bleeding to death from a small-calibre bullet wound in her neck.

Brooks was tried in November 1977, two months after the first stocking strangling. At the start of the case, District Attorney Mullins Whisnant objected to every African-American in the jury pool, in order to ensure that the twelve men and women who would decide Brooks’s fate were white. At the end of the penalty phase he made his closing appeal, imploring the jury to send Brooks to the electric chair: ‘You have looked at William Anthony Brooks all week, he’s been here surrounded by his lawyers, and you’ve seen him.’ Having seen him, of course, the jury knew he was black.

Brooks, Whisnant said, had treated Jeannine ‘worse than you would a stray animal’. Not content with ‘raping her, with satisfying his lust’, he had let her die ‘very slowly, drip by drip, drop by drop … if you sat down and tried to think up a horrible crime, could you think anything more horrible than what you’ve heard here this week, that this defendant committed on this young lady? Could you think of anything more horrible?’

The defendant, Whisnant said, might be only twenty-two, but rehabilitation was quite impossible: he had been in trouble since he was a child. (As a teenager, Brooks had been arrested for car theft.) Fellow prisoners and guards would be at constant risk of a murderous attack if he lived. The defence was asking for mercy because Brooks had been brutally abused as a child, but for Whisnant this was just an excuse: ‘His sisters talked to you about him being beaten by his stepfather, but they never did say what his stepfather was beating him for. Maybe he needed it. There’s nothing wrong in whipping a child. Some of them you have to whip harder than others. And there’s been children who have been abused and beaten, but they don’t turn to a life of crime on account of it.’

He concluded by appealing to the jurors’ social conscience. Columbus was fighting a war, and men like Brooks were the enemy:

And you can do something about it. You can bring back the death penalty and you can tell William Brooks, and you can tell every criminal like him, that if you come to Columbus and Muscogee County, and you commit a crime … you are going to get the electric chair. You can think of it this way. You know from time to time, if you were a surgeon, and you have people coming to you and maybe they have a cancer on their arm, and you look at it, and you say, ‘Well, the only way to save your life is to take your arm off.’ Or maybe he’s got cancer of the eye, and you have to take his eye out. Sure, that’s terrible, but it’s done because you save the rest of the body. And I submit to you that William Brooks is a cancer on the body of society, and if we’re going to save society and save civilisation, then we’ve got to remove them from society.

Amid the sea of white faces inside the courtroom, that last ‘them’ might easily have been interpreted as a reference not to tumours but to African-Americans. In less than hour, the jury voted to put Brooks to death.

Six years later, in 1983, the Federal Court of Appeals for the US Eleventh Circuit stayed Brooks’s execution eighteen hours before his scheduled death, because of its concern about Whisnant’s rhetoric and the exclusion of blacks from the jury. After another six years of bitterly contested hearings, Brooks was sentenced to life without parole. Removed from death row, the man whom Whisnant had deemed beyond rehabilitation took his high school diploma, and then began to study for a university degree.

The racial connotations of the murders of 1977 were not lost on those who had to investigate them. In a cavernous, oak-panelled suite at his thirty-seventh-floor office in Manhattan, blessed with a dazzling view of Central Park, I interviewed Richard Smith, once a Columbus detective, now the chief executive of the Cendant Corporation’s property division, Coldwell Bankers – the largest real-estate business in the world. The former cop was now responsible for twenty thousand employees, and an annual turnover of $6.5 billion.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.