Kitabı oku: «Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union»

ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Content

Abbreviations and Administrative Delineations

Introduction

Never Speak to Strangers

Impressions of Moscow: Beyond the Looking Glass

Soviets’ Long Queue to Nowhere

Angry Russians Can’t Understand Inflation

The Dissidents Who Strive for Western Freedoms in Russia

The Ghost in the Machine

The Price of Respectability

Taking a Healthy Rest

The Price of Soviet Achievements

A Burning Issue

From Russia Without Love

Trials of the Workers

The Price of Calling the Helsinki Bluff

Shaken, but Ready to Rise Again

Soviet Dissent and the Cold War

Why Moscow Has Georgia on Its Mind

Angry Nationalist Struggle Against Soviet Power

Afghanistan’s Rocky Road to Socialism

Russia’s ‘Civilised North’

Moscow Yields to ‘Interference’

Tensions Between Systems Show at Summit

Bitter-Sweet Search for Ancestors in Ukraine

The Crime That Can Only Exist Behind Closed Borders

Planning and Politics Strangle the Soviet Economy

Josef Stalin’s Legacy Leaves Soviet Leaders in Dilemma

Sakharov’s Arrest Links Dissidence with Detente

The Limits of Detente

200 Soviet Officials Held

Fighting a War of Shadows

Moscow Starts ‘Phoney War’ Over Peace

Why the Russians Think They Have Taken Schmidt for a Ride

Russia Through the Looking Glass

View from Middle Russia

How the Kremlin Kept Moscow Under Wraps

Russia Keeping Its Hands off Poland

Where Some Miners Are More Equal Than Others

Moscow Weighs Gains and Losses Against Dictates of Ideology

Soviet Defeat in Poland

Few Goods in Grocery Store 7

The Soviet View of Information

A Match for the Soviets

The KGB Puts Down a Marker

The System of Forced Labor in Russia

The Soviets Freeze a Peace Worker

What Russia Tells Russians About Afghanistan

The Legacy of Leonid Brezhnev

The Soviets Slam the Door on Jewish Emigration

Soviet Threat Is One of Ideas More Than Arms

Treating Soviet Psychiatric Abuse

The Kremlin Tortures a Psychiatrist

Yuri Andropov: The Specter Vanishes

Private Soviet Screenings of Forbidden Films? Insane!

In New Gulag, Soviets Turning to Murder by Neglect

Don’t Talk with Murderers

Moscow Feeds a Lap-Dog Foreign Press

Moscow’s ‘New Openness’ Illusion

A Test Case

Why Glasnost Can’t Work

A Journalist Who Loved His Country

Response to Fukuyama

Winter in Moscow

Setting the Sverdlovsk Story Straight

Moscow Believes in Tears

The Seeds of Soviet Instability

The Rise of Nationalism

Yeltsin: Shadow of a Doubt

A Tragic Master Plan

The Failure of Russian Reformers

Rude Awakening

Yeltsin: Modified Victory

Organized Crime Is Smothering Russian Civil Society

The Wild East

The Shadow of Aum Shinri Kyo

The Cost of the Yeltsin Presidency

The Rise of the Russian Criminal State

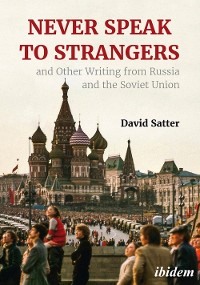

David Satter interviews Ida Milgrom, the mother of Jewish dissident, Anatoly Shcharansky, outside the courthouse in Moscow where Shcharansky was tried in July, 1978. In the background (center) is Kevin Klose, Moscow correspondent of The Washington Post (photo by Robin Knight).

The Human Rights Situation in Russia

Anatomy of a Massacre

The Shadow of Ryazan

Not so Quick

Death in Moscow

Stalin’s Legacy

A Low, Dishonest Decadence

Terror in Russia: Myths and Facts

Ordinary Monsters

The Murder of Paul Klebnikov

The Tragedy of Beslan

The Communist Curse

Stalin Is Back

What Andropov Knew

G-8 Crasher

Nikita Khrushchev’s Hard Bargains

Who Killed Litvinenko?

Boris Yeltsin

Russia on Trial

Land for Peace

Putin Changes Jobs—and Russia

Poisonous Patriotism

Obama and Russia

Who Murdered These Russian Journalists?

Obama’s Outreach to Muslims Won’t Achieve Its Goal

Putin Runs the Russian State —and the Russian Church Too

Mission to Moscow

Obama’s Russian Odyssey

Psyching out U.S. Leaders

The President’s Mission to Moscow

The Summit: Day 2

Natalya Estemirova

A Wounded Bear Is Dangerous

Pining for Authoritarianism

Remembering Beslan

Afghanistan: Lessons from the Soviet Invasion

Yesterday Communism, Today Radical Islam

A Passion to Relive the Past

Road to ‘Zero’

Symposium: Is Hannah Arendt Still Relevant?

Women Who Blow Themselves Up

A Hollow Achievement in Prague

Symposium: When Does a Religion Become an Ideology?

That Russian Spy Ring: The Broader Meaning

Never Forget: New Fanatical Ideology, Same Prescription: Defeat

Khodorkovsky’s Fate

Putin’s Facade Begins to Crumble

Why Putin Is Tottering

The Character of Russia

Obama’s Open Microphone

Russia’s Chance for Redemption

Russia and the Communist Past

Awaiting the Next Revolution

Clinton in the WSJ Strays on Russia Relations

Punk-Rock Authoritarianism

The Long Shadow of “Nord Ost”

Russia’s Orphans

David Satter on Life in the Soviet Police State

Russians Arrest CIA Agent

The NSA and the Soviet Union

Obama Defends Putin

Russia’s False Concern for Children

Putin and Obama in St. Petersburg

The Curse of Russian “Exceptionalism”

Snowden’s New Identity

Did Putin Insult the Pope?

Why Journalists Frighten Putin

Open Letter to Margarita Simonyan, Chief Editor of Russia Today

My Expulsion from Russia

Putin’s Shaky Hold on Power

The Russian State of Murder Under Putin

Putin Is No Partner on Terrorism

Russia Questions for Rex Tillerson

The ‘Trump Report’ Is a Russian Provocation

Trump Gives a Boost to Putin’s Propaganda

From Russia With Chaos

Trump Must Stand Strong Against Putin

How America Helped Make Vladimir Putin Dictator for Life

Who Killed Boris Nemtsov?

100 Years of Communism —and 100 Million Dead

A Christmas Encounter With the ‘Russian Soul’

How to Answer Russia’s Escalation

Putin’s Aggression Is the Issue in Helsinki

The Satirist Who Mocked the Kremlin —and Russian Character

When Russian Democracy Died

Contribution to “We Need Sakharov”

Collusion or Russian Disinformation?

A Pioneer Who Witnessed Revolutions

Hold Russia Accountable for MH17

Afterword to English Language Edition of Judgment in Moscow

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations and

Administrative Delineations

FSB — Federal Security Service

FSO — Federal Guard Service

IMF — International Monetary Fund

KGB — Committee for State Security

RUBOP (formerly RUOP) — Regional Directorate for the Struggle with Organized Crime

SVR — Foreign Intelligence Service

Krai — Province or territory

Oblast — Region

Raion — District

Okrug — Administrative subdivision, for example, of Moscow or military district

Introduction

The Marquis de Coustine, writing in the early 19th century, said that it was possible for a foreigner to travel from one end of Russia to the other and see nothing but false facades. In June, 1976, when I arrived in Moscow as the accredited correspondent of the Financial Times of London, I was confronted by a country that resembled nothing so much as a giant theater of the absurd.

I spent six years in the Soviet Union, from 1976–82. During this period, I sensed the uniqueness of the situation and began collecting the personal stories of Soviet citizens with the intent of preserving them for posterity. I was banned from the Soviet Union after 1982, allowed back in 1990, and finally expelled from Russia in 2013 on the grounds that the security organs regarded my presence as “undesirable.”

During these years, I observed four different Russias which managed to differ radically from each other while remaining essentially the same. From 1976 to 1982, I witnessed the Soviet Union at the height of its world power and a people in a state of ideological stupefaction. With the advent of Gorbachev’s perestroika, the Soviet population was liberated from the unreal world of the ideology and the state hurtled to its inevitable collapse. When independent Russia emerged from the wreckage, the failure to replace the missing ideology with a genuine set of universal moral values led to Russia’s complete criminalization.

Finally, the unreal world of the Soviet ideology took its revenge in September, 1999 with the bombing of four Russian apartment buildings that made possible Vladimir Putin’s rise to power and the resurrection in Russia of the Soviet Union in a different guise.

The imaginary world of Marxist-Leninist ideology never really went away because the issue was never its validity but rather its political effectiveness. Mentally subjugated individuals can be treated as raw material for the purposes of the state which is why an ideology is so useful. By the time I was expelled from Russia in 2013, the re-propagandizing of Russia had been long accomplished and Russia is in a state of ideological control without an ideology to this day.

As Russia evolved, the conditions of work for a journalist also changed. During the Brezhnev period, all official information was organized to confirm the truth of the imaginary world. Real information was available but it was unofficial and getting it entailed taking a risk. This accounted for the unique role of the Soviet dissidents. They took it upon themselves—and often paid for their efforts with terms in Soviet labor camps—to provide truthful information about historical events and the conditions in the country to diplomats and journalists. The best informed foreign journalists were those with the closest ties to dissidents.

During the perestroika period, the regime itself began to release information that, had it been published months earlier by a dissident would have led to the latter’s arrest. Gorbachev wanted to use limited freedom to, as he put it, “unleash the potential of socialism”. This was only possible, however, by lifting the dead hand of the ideology which meant free information. For journalists, this situation was nearly incomprehensible. The regime seemed to be organizing its own demise. But journalists were not the only ones who were confused. Gorbachev’s effort to reform the Soviet Union by undermining the credibility of its ideology led inevitably to the Soviet Union’s collapse.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, journalists faced a country that, while no longer communist, was taken over by criminals and so was not truly free. If the Soviet Union was justified by the myths of communism, Yeltsin’s Russia was justified by the myth of democratic, anti-communist reform. Foreign journalists could travel and write freely (although Russian journalists were frequently killed) but they had to struggle to distinguish appearance from reality. The endurance of the belief that the Yeltsin period was the flowering of Russian democracy is a tribute to the fact that very few journalists passed that test.

In September, 1999, Western journalists in Russia faced their greatest challenge as apartment buildings were blown up in the middle of the night and evidence mounted that the perpetrators were agents of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). The bombings were used to justify a new invasion of Chechnya which helped Putin to become Russia’s new president. Putin restored the institutions of the Soviet Union—false propaganda, militarism and hostility to the West. But as Putin’s grip on power tightened and the apartment bombings were followed by assassinations and new provocations, journalists largely restricted themselves to the official version of events, leaving the reality of Putin’s Russia concealed by ever more elaborate lies.

The articles in this collection are a chronicle of Russia almost from the day I arrived in the Soviet Union as a young correspondent in 1976 until the present. Depicted here are the things I saw, the people I met and the events I witnessed as reported by me to my readers in the West. In the broad sense, this is a record of one person’s attempt to penetrate the false reality of a country which was not like other countries but always sought to depict itself as something it is not.

Emigres from the former Soviet Union often despair of their inability to convey the truth of their experiences to the West. Arthur Koestler, a former communist and the author of Darkness at Noon, the classic novel about the Moscow purge trials of the 1930s, told a colleague that it was always the same with the comfortable and insular West. “You hate our Cassandra cries and resent us as allies,” he said. “But when all is said, we ex-communists are the only people … who know what it’s all about.”

In fact, it is not necessary to be an ex-communist to understand what it is all about. But penetrating the veil of Russian mystification requires effort and the ability to understand that seeing is not always believing. The Russians have created an entire false world for our benefit. The articles in this collection reflect my 40 year attempt to see them as they are.

Never Speak to Strangers

By David Satter

February, 1977

A bleak, overcast day in Riga had given way to a night that was clear and bitter cold. The red lights on the last car of the Riga to Tallinn overnight train glowed in the frigid air as the train backed into the station. I gathered my things and walked to the seventh car where I handed in my ticket and boarded the train. I entered my compartment and was surprised to see a young woman seated on one of the bunks. She had black hair, which was freshly set, a heart shaped face, pale complexion, and lovely dark eyes. I guessed she was about 28 years old.

I took off my coat, put my suitcase under the bunk and sat down opposite her. Two other persons soon joined us. The first was a tall, sandy haired man with broad shoulders who was wearing a heavy coat and a double-breasted jacket. He said that he was a boxing instructor from the Ukraine. The second was another woman in her 20’s, who entered the compartment carrying several packages. She was thin and bird like with a petulant expression. She had red hair and wore bright red lipstick. She said her name was Masha Ivanova.

As the train began moving, the attendant gave us back our tickets and brought us glasses of tea. Rivers and the skeletons of bridges passed by in the moonlight. The pale lights of occasional villages appeared and disappeared on the horizon and the train was soon rolling rhythmically through a landscape of pine forests and snow blanketed fields.

It occurred to me that it might be more than just a coincidence that a man and two attractive women my own age were riding in the same compartment with me but I decided that this compartment on a train between two Baltic capitals, on a quiet Saturday night—which the KGB was undoubtedly taking off anyway—was a sanctuary. I felt relaxed and, in any case, believed that members of my generation had something in common wherever we happened to be.

I decided to travel to the Baltics at the suggestion of Kestutis Jokubynas, a former Lithuanian political prisoner who I had met in Moscow. Kestutis and I agreed to meet in Vilnius and he promised to give me the names of contacts in Riga and Tallinn. But, being new to the Soviet Union, I also asked the Soviet news agency, Novosti, for help in setting up official interviews.

I arrived in Vilnius by train on February 15, 1977 shortly after dawn and met Jokubynas at my hotel. We took a bus to Kestutis’s apartment. Kestutis lived in a single room in a housing block in a new area of the city. A solitary window let in the gray light of an overcast day and the walls were bare except for a rectangle of barbed wire over the fold out bed, a reminder of 17 years that Kestutis had spent in the camps. Kestutis poured me a cup of tea. He said he had little hope that he would live to see an independent Lithuania. He then mentioned, almost as an afterthought, that the next day, February 16, was the anniversary of Lithuanian independence.

At 5 pm, it became dark. We traveled by bus to the Old City, the heart of historic Vilnius, a section of weathered stone buildings, winding narrow streets, and gloomy inner courtyards in the shadow of ornate Catholic churches. From there, we took a bus to see Antanas Terleckas, another nationalist, who lived outside of Vilnius, on the edge of the Nemencine Forest. When we arrived, Terleckas welcomed us and we entered a small room crowded with people of all ages who were sitting on worn couches and chairs. The conversation was about what would happen the next day with nearly everyone predicting a show of force on the streets as in past years on February 16.

Several of the teenagers said that they would try to put flowers on the grave of Jonas Basanavicius, the father of the Lithuanian national movement who, by an odd coincidence, died on February 16. The point of laying flowers on his grave was to mark the national anniversary. But if stopped by the police, they could pretend that it was a personal gesture on the anniversary of Basanavicius’s death. This would convince no one, of course, but the police could be counted on not to arrest them at the graveside because that would acknowledge their fear of nationalism which officially did not exist.

The dissidents described the Lithuanian national activity in recent months—underground journals, the raising of the old Lithuanian flag over the ministry of internal affairs, arrests. I filled up most of a notebook and agreed to meet with Jokubynas in front of my hotel at 7 pm the following night.

The next morning was cold and overcast. I went with my guide for an interview with a government official and in the afternoon, for a trip to a collective farm. On the way, our car stopped to pick up a man who said he was an agronomist.

We left the collective farm in the late afternoon and the agronomist proposed that we take tea at a nearby club. I was anxious to return to Vilnius but agreed and we drove for 20 minutes before arriving at an isolated house. Although we had supposedly come for tea, the table was set for an elaborate meal. The agronomist said the club contained a Finnish sauna. He referred to the sauna several more times and then, elbowing me gently, asked, “How would you like to try it out?”

An hour passed in increasingly stilted conversation. Finally, ignoring the agronomist and addressing the guide, I said I wanted to leave. This brought an angry response from the agronomist who said the time had come to try out the Finnish bath. The agronomist, the guide and the manager of the club began chanting, “Finnish bath, Finnish bath.” I finally got up, took my coat and walked out to the car. It was only after I stood outside for 15 minutes that my guide and the agronomist joined me and we rode back into town.

I arrived in Vilnius at 7:30 pm but there was no sign of Jokubynas. I called Valery Smolkin, one of his friends. He said Kestutis had probably been arrested and suggested I come to his apartment to wait. I caught a cab and we turned down one of the side streets where I saw the scene that had been predicted by the nationalists the previous night. At each corner, uniformed police surrounded by milling crowds of obvious plainclothesmen were stopping passersby and checking their documents. The cabdriver, a Russian, said a policeman had been shot in a robbery of the state insurance company.

I arrived at Smolkin’s apartment at 8:40 pm. Three hours later, there was a knock at the door and Smolkin opened it to Kestutis who took off his coat, which was wet with newly fallen snow. He said that he had been on his way to meet me in front of the hotel when he was surrounded by five plain clothesmen. He was taken to a police station, the same one where he was taken after his first arrest in 1947, and put in a cell. He was then interrogated by a police officer who appeared drunk and spoke in a weird combination of Russian and Lithuanian and told him he was a suspect in the robbery of the state insurance company.” “I’ve been in the camps,” Kestutis said, “I’m not going to participate in your comedy.”

In the end, we spoke for several more hours and Kestutis gave me the address of Ints Tsalitis, a Latvian nationalist in Riga and the names and addresses of dissidents in Estonia. He also made one request. He asked me to make sure my notes from Lithuania never left my hands. I agreed and at that moment, I certainly intended to keep my promise.

The next morning I flew to Riga. The train from Vilnius to Riga was closed to foreigners. After I checked into my hotel, I realized that I had filled a notebook in Vilnius and would need a new one to interview city officials. I had promised the Lithuanians that I would keep my notes with me but the notebook was an awkward size. I finally forced it into my jacket pocket and left for the interview. That afternoon, however, I put the notebook in my suitcase and locked the suitcase in my room, leaving the key with the room clerk downstairs.

When I returned to the hotel, it was already dark. I asked the girl at the reception desk for the key to my room. But she looked and said she could not find it. I went upstairs and asked the floor attendant but she did not have the key either. I was now seriously worried. I went out for a walk. When I returned, I asked the girl at the desk to check again for my key. “Here it is,” she said, reaching into a slot in the key rack, “it was here all along.”

I took the key and went upstairs to my room. The light of the street lamps cast a pale glow in the darkness through the room’s nylon curtains. I opened my suitcase and saw that the notebook from Vilnius was still there. Everything appeared untouched.

I put the notebook back into my jacket pocket and caught a cab for Vecmilgravis, outside of Riga, to meet Tsalitis. I arrived at his home at 9 pm. He welcomed me and, as we sat in his kitchen, I told him about the events in Vilnius and warned him that I was probably being followed. He put on his coat and went outside with his dog, a large St. Bernard. When he came back, he said there was a black car parked at the end of the street with four men in it. “They’ve probably been there for several hours,” he said. “They don’t have to follow you. They know there are only a few places for you to go. It saves them time and energy.”

Tsalitis said that, in general, the situation was quieter in Latvia. There were no active dissident groups or samizdat journals. “The Latvians find it easier to get along with others,” he said. “It’s a virtue but it’s also our tragedy.” A half an hour later, Viktors Kalnins, another nationalist, joined us and he and Tsalitis gave me the names and addresses of Estonian nationalists in Tallinn. I wrote them on a separate piece of paper but they were the same names Kestutis had given me in Lithuania.

The next day in Riga I visited another collective farm. That evening I checked out of the hotel and prepared to go for a walk. Once again, I had to decide what to do with my notes. I had put the notebook in my suitcase. But I did not want to take a walk carrying a suitcase. I decided to leave it with the doorman. When I returned, I opened the suitcase. It appeared that nothing had been touched.

It was only on the night train to Tallinn that I began to feel at ease. The coach poured out drinks for each of us and Masha asked me where I was from. I told her that I was an American and that I was working in Moscow for the London Financial Times.

The coach asked what women were like in the United States. I said that they were better dressed than Soviet women but not necessarily prettier. Masha asked if I believed in God. I said that I did. This puzzled her. “Here, no one believes in God,” she said. I then began to explain my views. As I continued, trying to make sense in less than perfect Russian, Masha moved slightly forward, leaning over the small table and resting her chin childishly on the rim of one of the tea glasses. The dark haired girl also fixed her eyes on me and, inexplicably relaxed, I motioned to Masha to sit beside me. She complied and although I tried to continue what I was saying, she put her arms around me and began kissing me. The coach immediately went over to the other bunk and started kissing the dark haired girl, holding her in his arms and pressing her breasts against him.

This situation did not last long because the two girls almost immediately told us to go into the corridor so they could make the beds and get undressed. Most of the other passengers in the car had retired for the night. As we waited in the corridor, it occurred to me that the women in the compartment, the offer of easy sex, were the standard techniques of entrapment but it was exactly this that allayed my fears. Putting women in an overnight train compartment was too obvious. If the goal was entrapment, the KGB would have tried something less primitive. The idea that my new friends had been seated in my compartment for no other reason than to compromise me was just too incredible to believe.

When we entered the compartment, the women were in their nightgowns. Masha was sitting on the upper bunk, her breasts and a crucifix visible through the opening of her gown. The dark haired girl was lying on her side on the bottom bunk. We began to undress and the boxing coach turned off the overhead lamp so the only light came from the reading lights above each of the berths. I climbed into the upper berth and the coach got into the lower berth. The small lights were then turned off, leaving nothing to illuminate what went on until several hours later when the first filtering rays of sunlight indicated the break of day.

During the night, I was troubled by a strange dream. There was an indistinct image of the dark haired girl moving around the compartment as if she was making preparations to leave. After I had opened my eyes, I became concerned about my suitcase. I pulled on my pants and climbed down from the upper bunk. The fields and forests looked blue in the early morning light. The coach was already dressed and sitting on the opposite lower berth. The girls were asleep in their beds. Joking with the coach, I reached for my suitcase. It was then that I discovered that it was gone.

Suddenly, the coach began feeling the pockets of his jacket. “Wait a minute,” he said, “my watch is gone!”

He looked down at the bunk where the dark haired girl was sleeping, curled up in a tight ball facing the wall. He pulled back the top blanket and under it found other blankets tightly rolled from the inside out and arranged to create the impression of a sleeping person. I woke up Masha Ivanova and asked her what she knew about the dark haired girl. She said that she had met her that evening for the first time. I called the attendant and asked her if she had noticed anyone leaving the train in the middle of the night. I explained that I had lost my suitcase and the boxing coach had lost his watch. She promised to alert the police.

The train arrived in Tallinn at 8:30 am and we were met by the police and taken to their headquarters in the station. The police made clear that they viewed the case with the utmost seriousness. They insisted that we write detailed statements and stressed that any omission could impair the investigation. The coach and Masha wrote their statements and then Masha helped me to write mine. Reading the statements, the officer in charge began to wonder. “Two men and two women in one compartment,” he said, his voice trailing off thoughtfully.

I now faced a dilemma of my own making. My notes from Lithuania were gone. It was urgent that I find the Estonian dissidents whose names and addresses were in my suitcase. Fortunately, I also had written them down on a piece of paper that was in my wallet.