Kitabı oku: «A Reply to Hate: Forgiving My Attacker», sayfa 3

Chapter 3

Hospital

This is insider information, but if you are unfortunate enough to be stabbed in Manchester, it is very likely that you would be rushed to Manchester Royal infirmary. This is neither my local hospital nor the hospital I work at and I did not want to end up there. I had somewhat cheekily asked the ambulance crew if they would take me to my local hospital. It was my decision, and I wanted to be treated where everyone knew me. By the time the ambulance arrived at the hospital I was no longer strapped to the scoop looking at the ceiling. I was now sitting slightly up, starting to get a sense of my surroundings.

As per protocol, the ambulance crew would have called in the incident and the trauma team were waiting, ready to receive the injured victim. The team would normally include one of my orthopaedic trainees, but it also happened that at the time, one of my consultant colleagues was attending the emergency department along with the on-duty orthopaedic registrar. I did not expect that they would be present, but equally, no one had a clue who the victim was. Later, my consultant colleague informed me that on that afternoon, she was about to leave but decided instead to wait in order to make sure her services were not required. She was not prepared for the shock that would hit her. No one was. As I was wheeled into the resuscitation room the stretcher gradually turned around and I came face to face with my colleague and trainees standing side by side. I instinctively smiled at them, but all I could see was three white faces, wide eyed and totally stunned. The site of my junior trainee was unforgettable. His jaw literally dropped, and I watched his face turn white. They were totally dumbfounded, but they rushed to hold my hand and comfort me. The reality was that they also needed some comforting, some reassurance that I was alright. The shock on their faces at that moment was priceless, but in that moment I could see what they meant to me and what I meant to them, and I was grateful to be there with them.

It did not take long before we all had to snap out of this emotional encounter and start acting professionally. After all, there was a potentially critically injured patient in need of emergency assessment and care. Despite their initial resistance, colleagues were formally asked to vacate the resuscitation area while the accident and emergency team took over in order to begin their standard ‘resus’ protocol. They were very professional and equally courteous. For a victim with a penetrating injury, the immediate imperative is to make sure that there is no imminent threat to life. This may sound gruesome, but it is essentially making sure that a) the victim is breathing soundly and b) not bleeding to death. Once these are checked, the examination then follows a well-defined structured and systematic sequence to determine the nature and extent of the ‘primary’ damage. In essence, this involves looking for the immediate damage caused by the knife penetrating my neck. The young A&E doctor proceeded to examine me, much as I did in my own assessment earlier. Of course, he had to get it right and to his credit he did not seem to be phased by the fact that he was examining a senior colleague, knowing full well that his own competence was also being assessed! By the end of his examination, it was reassuring to learn that I had not missed anything earlier! The nurse took my vital signs again—pulse, blood pressure and oxygen saturation—before starting to prepare another intravenous drip. It was simply not my day. The A&E doctor had the last laugh. Once he finished his assessment he smiled at me and said, “I need to put another needle in your left arm.” I remembered why; for a penetrating injury, two large bore cannulas, one in each arm, is the standard Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol. After all, I was an ATLS instructor, and I should have seen it coming. For the second time that day I opened my arm and held my breath.

It was a very unusual experience for me to be on the receiving end of an examination that I had so often carried out and to see how this young A&E doctor was trying to reassure me and keep me calm about what he was doing and why. Once he cleared my arms and legs, he asked me to lean forward so he could examine the back of my neck. He told me the wound did not look dirty and was not bleeding much, nonetheless I still needed to have a tetanus jab, so that meant, yes, another needle. With my surgical background, I knew very early that the penetrating knife has missed all the vital structures in my neck, but I also knew that I had to go through a rigorous examination just the same. I wasn’t frightened or distressed, and I found myself reassuring others that apart from the pain, I was feeling fine and calm. Perhaps if I was not a doctor, I would have felt very different. But there I was, in very familiar surroundings and with people that I knew, going through their usual business, all of which was very comforting for me. Even though I was aware that so far I was ‘clinically stable’, I knew that the A&E doctor would still consider me to be in a potentially critical condition. The potential for secondary life-threatening internal damage needed to be excluded before I would be off the critical list.

Once he finished his initial assessment, the young doctor informed me that I would soon be going for a CT scan of my neck, and he left the bay. As he left, a young, awkward-looking police officer entered and requested a statement. I had been expecting to see the police at some stage, but I wasn’t sure why this particular officer looked out of sorts, uncomfortable and anxious. It was the first inkling I had that there were perhaps wider implications of the attack. I cannot recall exactly how the conversation went, but I remember he wanted me to go through the incident in as much detail as I could recall. Unfortunately, his awkwardness only increased during this questioning when Syrsa walked in. The questions just stopped, or probably I just stopped listening to them. I looked at Syrsa’s face and I could see she was calm. She wasn’t pale, she wasn’t hyperventilating, she wasn’t anxious, she just walked towards me and held my hand. I told her I was okay and she nodded to say “I know you are”. Her immediate words were “I’m so grateful to God”. I think when she first saw me, she could immediately tell there was nothing horribly wrong as I was sat up talking to the officer. It was probably that first eye contact as she entered. Perhaps I smiled and shook my head. She is a doctor herself, and when she saw me sat up on the trolley, she saw for herself that I was OK. We did not say much to each other; I was alright, and probably that was all that mattered.

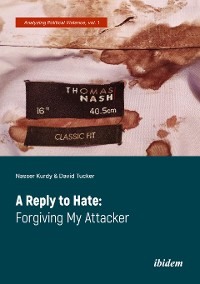

The officer just stood there waiting for his moment to barge in, which he eventually did. But then it came to that critical question, “Do you remember what he said to you?” Up to that point, I never really thought about what my attacker said to me. It was then that I had to start remembering what was shouted at me as it might give a clue to why I was attacked. I clearly remembered walking onto the grounds of the mosque, I clearly recalled the moment of sudden pain and I clearly recalled the look on his face, but for the life of me, at that moment, I could not recall exactly what he said. As I struggled to remember, I think I mentioned to the officer that I recall he swore at me. Then I think I said that he had uttered one sentence, just one sentence, and that was all that I could come up with. Somehow, I found it difficult to recall his exact words and I wasn’t sure why. I told the officer that I needed some time to remember. To be honest, I was somewhat disappointed with myself that I could not recall what had been said. But even then, I was conscious of the fact that I should not put words into someone else’s mouth, and I needed to be careful as to what I might say. I may have told the officer that I would need to think this through more carefully and it would probably be the following day before I could complete my statement. But then came yet another embarrassing moment for a victim. The police officer asked me to get undressed and to give him my clothing as it was now ‘material evidence’. I proceeded to get undressed and gave him my shirt, my trousers, my belt and my socks. Fortunately, my underpants did not qualify as material evidence. Syrsa was not happy at all; the shirt and the belt were new, and they suited me! In any case, I thought what the heck, I am going to stay the night at the hospital as they would most likely need to observe me overnight. As for my shoes, I was somewhat lucky as they were still on the shelf at the mosque and thankfully they were not seized. I was now down to my underpants! I looked at Syrsa and we both laughed at the silliness of the situation as I tried to cover myself as much as I could with the flimsy trolly sheet. Syrsa then told me that around thirty people were waiting outside to make sure I was OK, and we agreed that she should go out and let everyone know that I was fine and to get the word around that the immediate worry is over. As she left, I closed my eyes and started to replay the earlier events to help me remember what the hell this young man had said to me.

Soon enough, the nurse returned to recheck my vital signs. At some stage I was given a strong analgesic for my pain, I think morphine, and it was ‘titrated’ in. As I saw the injection going into the cannula, I waited for that extraordinary experience of having morphine in my veins for the first time in my life. I waited in anticipation for this so called ‘trip’. This would probably be the only time I could legally experience such a trip, but sadly nothing happened, one of the more disappointing aspects to that situation. Anyhow, the nurse ran some more fluid through the cannula and everyone was ready for me to go to the CT scanner. This was the only trip I had that evening!

A CT scan is standard protocol for a penetrating injury. The scan is necessary to identify the depth of the injury and to check for internal bleeding, which is bleeding that does not gush out through the wound but stays inside the body and can put pressure on, and so cause damage to, vital structures. A few minutes later I was wheeled into the scanner room and was asked to slide myself from the trolly onto the narrow scanner bed. With a cannula in each arm, a drip line on the left and a painful neck, I was trying desperately to keep my dignity with this flimsy trolley sheet. But then I thought, at least for this night, I should just be a patient and give up on being ‘dignified’; it can’t get any worse. As part of the scan routine, a contrast dye needs to be administered through one of the cannulas. This contrast flows through the blood stream and has the ability to highlight blood vessels and so, most crucially, it can highlight internal bleeding. The protocol is for a scan sequence to be done before and after the contrast dye is injected. If there is an area of bleeding, the contrast will seep out where the bleeding is, and this can be picked up as a difference between the two scan sequences. I remember a warm feeling up my arm when the contrast went through me and I think I also felt a strange taste in my mouth, but nothing unduly unpleasant. A quick glance at my scans showed that the bleeding was very minimal and fortunately there was no major, or even minor, vessel damage. This was a big relief to everyone as the carotid and jugular vessels were very near to where I was stabbed. The smaller vertebral arteries were also missed and even the little veins that lit up on the scan were cleared by no more than a millimetre. None, absolutely none, of the important structures in my neck were harmed. The knife tore through my neck muscles with almost surgical precision, avoiding everything. The scan was quickly and formally reported as showing no primary structural damage, which I already knew, and no potential secondary damage, which was obviously good news. I was now officially off the critical list and everyone could take a deep sigh of relief. I believe my consultant colleague was soon notified, and she in turn passed the message to all my immediate work colleagues. The journey back to the resus room involved another gliding manoeuvre from the scanner bed onto the trolly, but by now I didn’t care much about the effectiveness of the trolly sheet.

Soon I was back in the resus room, where the A&E doctor reassured me again about the scan findings. He then proceeded to clean and stitch my wound. We always say “This won’t hurt much” as the local anaesthetic is being injected, and yes, I never really believed that myself entirely when I would say the same. But now I was on the receiving end, and it did hurt, even though the doctor kept on saying, with confidence, this won’t hurt much. I thought “Better keep my mouth shut and not have him become more anxious than he probably already was.” I still recall feeling every stitch. I thought I counted five, but later found them to be only four! I remember keeping very still and very quiet. He then asked me if I felt anything. Well, what could I say? By then Syrsa came back in to hold my hand and everyone was expecting that I would spend the night at the hospital. I was still lying there in my underpants when the A&E doctor said, “Dr Kurdy, you’re all clear, you can go home now.” Syrsa and I looked at each other and our immediate thought was that there was no way I was going to walk out like this! Fortunately, I was able to get a colleague to fetch me some scrubs and a pair of clogs. The cannulas were pulled out and Syrsa helped me get dressed. I sat at the edge of the trolley for a couple of minutes to make sure I didn’t feel faint and then stood up and leaned on her. I felt OK; we were ready to go home.

As we were walking out along the hospital corridor and we saw friends waiting, I started to realise the commotion that was simmering out there. There were about thirty people waiting for me and I started to get a sense of how they were interpreting the attack. Now that the concerns about my health had settled, I sensed anger, and for the first time I started to feel uncomfortable. Very early on, friends were already questioning things such as why me, why at the mosque? Throughout my time at the hospital, which probably took no more than two hours, I was virtually secluded and was totally unaware of what was unfolding elsewhere. A hospital’s resus room is a very particular type of place, and your mind does not take you much beyond where you are. At no time did I consider what might be happening at the mosque, never mind anywhere else. I was unaware of what the police had been doing and naïvely I had not expected the media to have been informed. However, it gradually transpired that it was nothing short of mayhem and I knew absolutely nothing about it.

I think if it hadn’t been for us sending reassuring messages telling people not to come to the hospital, there would have been about three hundred people there. My stabbing had all the hallmarks of an Islamophobic hate attack. My community already felt vulnerable and under threat. The police had a potential terrorist case on their hands and the media had a story to tell. It was not taking much for people to start making up their own stories. I later found out that our Islamic centre and the police had already released official statements regarding the incident and I also became aware that an urgent meeting was planned for that evening, which would include representatives from the CPS, the police and members of the local Muslim community. Serious questions needed to be addressed: was this a planned attack on the mosque; is there an extremist background to this crime; was the immediate safety of our neighbours and the wider community at risk? I presume the police would have also been concerned about the potential backlash from such an incident. It was reassuring when I found out about this meeting and the fact that such questions were being taken seriously at a high level. It was partly as a consequence of this meeting that it was decided the attack would be officially classified as a hate crime.

By the time we arrived home, the short video taken soon after the stabbing had already been viewed in Pakistan, Jordan, Iraq, Israel, Russia, Australia and the UAE! It was on a global trip. The heading did not need much elaboration: “Muslim Imam and surgeon stabbed in an unprovoked attack as he entered his local mosque”. The sentiments were already heading in one direction and feelings were running high. However, as we arrived home and opened the front door, all seemed finally calm. We asked friends to give us some privacy that evening, reassuring everyone that we were fine, but we just needed time to recover and, God willing, we would take things from there the following day.

Both of my sons were at home when we got back, Ahmad is the younger, then 13, and Oaiss was 20. They both knew early on that I was OK. When we arrived home, they were calm and relaxed and already back on their computers. The house felt calm with no excitement and very little commotion. I did not feel like watching TV and Syrsa and I just wanted to sit together and get our breath back. My daughter Assma lived in London then, though at the time of the incident she was on a short break in Barcelona. She had already gotten the news and seen the short video! She needed to hear my voice and we quickly phoned to reassure her.

Even though I still felt calm, I was in agony. My neck was hurting a great deal and I had to move very slowly, taking my time, taking things easy. I sat with Syrsa in a small room next to the kitchen. Strangely, we did not feel comfortable sitting in the living room somehow, we needed to feel cosy and close to each other. Messages started to flood in via various routes. It was a surreal experience reading “Your story is now in Pakistan, you’re on Pakistani TV: ‘Muslim Imam Stabbed in the Mosque’”, though at this point I still had no clue that there was a video. The person who recorded it was very discrete, and I don’t think anyone knew about it until they were watching it later. Some of my friends were unhappy that this took place and expressed concerns that it intruded on my privacy. In all honesty, and seeing how the story eventually unfolded, I could not begrudge what he did. That short video depicted a genuine moment and genuine expression, and it became the focal point of my experience. Without it I would only have memories, and I cannot be thankful enough that these images exist. I remember speaking to my sister that evening, who lives in the UAE, but all I can recall from the conversation was her crying her heart out. She is my only sister, and she needed a great deal of comforting and calming down, especially after she saw me grabbing onto my neck in agony; the video was already there.

As we sat alone in that little room, I quickly became disinterested in what was taking place outside. Both Syrsa and I felt we were not yet ready for it all. It was distracting from what we felt was most important to us; the fact that I walked away virtually unscathed from a stabbing in the neck. I recall we sat together on our own, facing each other, and we were fairly quiet, just looking at each other and smiling. I then asked, “How do you feel?” She said, “I feel the mercy of God has touched you today.” She said it in Arabic, and the word we use for mercy is رحمة. At no point did she mention anger or frustration as to why this happened to us. She never questioned “What the hell happened to you” or “Why did he pick on you”; none of that. She did not feel threatened or vulnerable. She just kept on saying “I feel the mercy of God has touched you today”. But then she said something that is perhaps meaningful to people of faith but may not be fathomable by others. She said, “I feel an Angel held his hand”, “his” being the attacker. That was the feeling running deep in her heart. She knew the knife could have gone anywhere in my neck, and she felt that in her heart as this man thrust the knife in me, an angel grabbed his hand. I am not sure, but I think it is fair to say that Muslims and other people of faith tend to rationalise events in their lives based on their faith and the strength of their beliefs. We believe that there is a God, we believe in angels and we believe that there is a higher purpose in life. I know that this does not sit comfortably with some people, and I also know that some may view this as downright stupid. But that is who we are. Such belief is imprinted within our psyche and makes Syrsa and I who we are. The two of us differ in many ways from each other, but when it came to faith, I told Syrsa that this was exactly how I felt. Not the slightest hint of anger came to my mind, or indeed any negativity. I just felt I was blessed, and that God was merciful to me.

But then, and as we sat there talking, Oaiss walked in. He had been at his computer and he asked us if we realised what was happening on social media. Of course, we didn’t. “They’re starting to get angry” he told us. I had not read much of what was being circulated online, and in all honesty, I really did not feel it was time to engage yet. However, my son’s intrusion triggered something within me right there. I had sensed the anger earlier as I was leaving the hospital and now this. The calmness that we were feeling was not being mirrored by everyone else. On the contrary, it was exactly the opposite, and this did not sit well with me at all. I told my son we needed to send a message right now. It needed to be simple, clear and explicit; we did not want anyone to retaliate or to promote anger or hate. I remember that the message ended with “My father is not angry; he doesn’t want anyone to be angry on his behalf.” I just asked Oaiss to pass it to his friends and let them pass it on. By now, that air of contemplation and calmness was gone, and I felt very early on that I was already being forced to take a stand. If there was anger and frustration surfacing that evening, it was because of that. It just did not seem to me to be the right time to have to deal with that sort of behaviour, but there was little I could do about it. On reflection, and despite how I felt, I am grateful that this surfaced early as it had the effect of resetting my mood. Whether I liked it or not, my stabbing was somehow bigger than just ‘me’ and I felt I needed to step up. This changing perspective may well have had a big impact on how I started to think and behave.

Later that night we were visited by two police officers checking to see if we needed any help, probably just before midnight. We assured them that we were fine. We didn’t feel scared or vulnerable and by then we were again feeling calm. It may have seemed strange, but there we were like any other day ready to go to sleep. We switched everything off and went upstairs to bed. After all, it was Monday the following day and we needed to get ready! As Syrsa went upstairs that night, she literally hit the bed and fell asleep. So did my sons. But I could not sleep. Whichever position I took in bed, within a couple of seconds I was in agony. Even though I knew how to handle my pain, still I was in agony. I tried resting on my back, my side, curling the pillow and so many other positions, but the pain just kept on banging through. To some extent I now empathise more with my patients. Previously, I would perhaps wonder what they meant by “agony”, but now I knew. I think I took another couple of codeine tablets in the middle of the night and this at least eased the pain enough to allow me to think. I was trying hard to remember what this man said to me. But also, I was thinking through what could have happened if that knife had touched my spinal cord. The overwhelming sense that I had was of being grateful to Almighty God. The Arabic phrase is الحمد لله (“al-hamdulillah”), an expression meaning “All praise be to Almighty God”. These two words roll easily off the tongue. Throughout the night I was repeating الحمد لله. It somewhat temporarily distracted me from the pain, until I moved again. All night I was thinking “Thank God I’m still alive, thank God it wasn’t worse”. But one other thought that occurred was that since the moment I was stabbed, I had not done anything good, anything thankful. To simply say “Thank God” does not really cut it, so I promised God that as soon as I woke up in the morning, I would make a donation. But before that, I still needed to fall asleep. I remember I asked God, “Help me sleep”, “Come on God help me sleep”. But pain is pain, and no matter what I did, I could not get into any comfortable position. My head felt so heavy and the pain went on throughout the night, until finally, about 7:00am, I dozed off.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.