Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Rewilding», sayfa 4

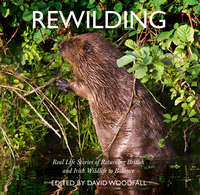

Rewilding site, Kielderhead Nature Reserve.

Kielder’s Wilder Side

Mike Pratt

Kielder wildwood is a wilding project with an especially big ambition. It is a woodland restoration and creation project in its own right, but is also conceived as a means to a much greater goal – that of integrating degrees of restored natural processes across the vast landscape of forest and open land between Whitelee Moor on the Scottish border and the whole of the wider Kielder Forest and Water Park landscape. Indeed, the wider vision is to extend this wilding approach across the Scottish border and to complement the already largely rewilded Border Mires – one of the largest restored peatscapes in England.

Thus, we are working with our partner landowners the Forestry Commission and Kielderhead (cross-border) Committee and others, to make all of the area wilder by degrees, recognising that even within the commercial forestry areas, there are already integrated wild lands, such as impressive riparian corridors. If nothing else, this Kielderhead wildwood concept is ambitious and certainly landscape-scale – more a ‘future proofing’, area-wide approach, than a mere project.

Part of the vision is very much about creating a ‘forest for the future’, a more natural, open montane woodland of mainly native species, with a more complete ecosystem over the longer term. Initially, this will focus on a 94 ha area of the Scaup Burn valley, which will be planted with 39,000 trees over three seasons, all by volunteers.

We recognise we are starting not in prehistory but in the twenty-first century, in a commercially important, working forest context and we have reasonable acceptance of this in species-mix selection, management and establishment techniques.

This vast area of open land runs for over 8,000 ha up to the Scottish border. Today many of the hillsides beyond where plantation forest is still maintained are devoid of trees and, because the blanket bogs on top of the moors are important open landscapes in themselves, tree cover is actively discouraged. Large areas have special conservation designations to protect their special habitats and species, though often such land has the marks of human interference, being prepared long ago for possible forestry use.

The idea is to create ‘future-scape wildwood’, which has elements of species and habitat that thrived in prehistoric times here when the ecosystem was more complete. We aim to plant locally appropriate species such as downy birch and rowan, willow (some of which is already recolonising areas), juniper and many other species.

People are closely involved, despite the area’s remoteness. We started gathering local seed early on, including from rare old pines, growing seedlings with a view to planting to local seed stock. We draw additional inspiration from historic and prehistoric perspectives locally.

One key feature is a group of old Scots pines, the ‘William’s Cleugh Pines’, long thought be possible remnants of ancient or even prehistoric lineage – if true, they would constitute the first confirmed specimens of native English Scots pine.

Genetic work that has been carried out is inconclusive, but nevertheless the possibility remains of Scots pine being a surviving component of prehistoric forests. Evidence of the ancient forests is seen in the peat beds underlying the site and exposed in banksides and the burn – a layer of horizontal forest dated to 7000 bce, including pollen and preserved evidence of pine.

In addition to this, a branch was discovered in the side of the burn that dated to the fourteenth century and clearly exhibited beaver activity! In these historic remains we have perhaps some historical precedent, if we needed it, to develop a restored and more natural ecosystem.

Thus far we have initiated a massive volunteer effort in the middle of nowhere and started the establishment phase – the rewilded landscape is already taking shape, with 7,000 trees planted in the first year. We bid for and won Heritage Lottery funding, which is now enabling staff, volunteer effort and material planting and development of the project. We’ve brought on board world-renowned experts and undertaken micro-propagation from those old pines.

We are also addressing the cultural resonances of this remote part of the Anglo-Scottish landscape, a disputed land for centuries and perhaps also in the future, as border politics have definitely not completely gone away. Allied to the wildwood project we have successfully undertaken the Restoring Ratty project, aiming to restore water voles to the catchment.

What then might the future look like in decades to come? Ecological change is a certainty, natural processes will be restored, more natural and complete ecosystems come into effect and this should include the restoration of absent species.

Despite the very man-made nature of Kielder Forest and Kielder Water, the scale and breadth of wooded and open habitats across the whole area makes for a very natural feel, similar in character to parts of Scandinavia, and it is already surprisingly diverse relative to other areas of the UK.

Kielder already carries significant populations of key species like red squirrel (largest population in England), roe deer, badger, tawny owl, otter, wild goat and now, once again, water vole. Pine marten are recolonising themselves, golden eagle have just been reintroduced over the border and we hope may re-establish. We have osprey and other rare raptors that have come in – and a very wide range of bird, amphibian, reptile, insect and plant species, as expected.

So, in the future it can be envisaged that this rich range of species will be strengthened and extended – and joined, eventually, by beaver and even, perhaps, wildcat and other larger predators and herbivores: judiciously reintroduced after proper inclusive consultation and preparation. Reintroduction of species is only a long-term aim here and not the prime focus of the wildwood and Kielder in these early stages. Habitat restoration and development, though, will tend to lead the way to this.

This is a large, potentially resilient, forest area and, as it becomes more naturalised, will develop a sophisticated ecology. Balanced against this will always be the needs of commercial forest interests and the views of local farmers, and communities who live here and manage large areas nearby for other complementary uses. They too are part of the developing ecology of a ‘Wilder Kielder’.

Oak woodland at sunset.

Minimum-Intervention Woodland Reserves

Keith Kirby

The composition and structure of British woods has been shaped by centuries of management. However, in the second half of the twentieth century many semi-natural woods were left alone, either deliberately set aside as minimum intervention reserves, or left largely unmanaged because there was no market for the timber. Most of these areas are small, typically a few tens of hectares; mostly young-mature stands with dense canopies.

Such reserve areas were set up in Wytham Woods under the guidance of Charles Elton, shortly after the woods were donated to Oxford University in 1942/3. He later commented:

It is … clear that Wytham Woods have not for many centuries been ‘virgin’, though if given the chance to do so they might well return to something resembling a natural woodland, even if this would be different in composition from the original Saxon forest. What could be more fascinating than to watch this happen and record its progress over a hundred years or more, armed with the methods of modern ecology?

(The Pattern of Animal Communities, 1966).

He did not use the term rewilding, because it had not yet been coined, but some of the underlying ethos is in this quote: recognition of past management effects, a willingness to step back from future intervention, an implicit acknowledgement that this could lead to unforeseen changes.

Another Oxford ecologist, Eustace Jones, was at the same time making baseline records in what has become the best-documented example in Britain of a minimum intervention reserve at Lady Park Wood in the Wye Valley. Subsequently George Peterken and Ed Mountford have described the changing fortunes of different tree species in the face of disease, drought, mammal attack and falling off cliffs. Lady Park Wood has had highly dynamic tree and shrub layers – other stands, such as that at Sheephouse Wood, have shown very little change over 35 years, apart from a few individual oak tree deaths.

Underneath the canopy, the ground flora of these rewilded unmanaged broadleaf woodlands has tended to decline in species richness at the plot level: light-demanding species are particularly affected. Dead wood has generally increased, although evidence for increases in associated specialist invertebrate species is limited. Losses of existing veteran trees that have become overtopped by younger growth have not necessarily been matched by new ones developing due to stand age structures.

The original ‘non-intervention’ intention has often had to be set-aside: increases in deer range and abundance since the 1950s have forced interventions (fencing, culls) because of the small size of the stands. Trees by paths have sometimes had to be felled for safety reasons. There may be future human-induced changes due to the build-up of nitrogen in the soils from emissions from nearby roads, power stations, etc.

Large-scale rewilding has emerged independently as part of the conservation toolbox in the last decade, but there are lessons that can be learned from studying the longer-running minimum intervention woods.

Different sites will follow different trajectories and the long-term outcomes are not always predictable.

Species may be lost as well as gained; areas may become less diverse in the short term as the effects of past interventions fade out, even if there is scope for longer-term diversification.

External pressures may require some form of human intervention from time to time.

Rewilding is an exciting approach to conservation that should run alongside existing species and habitat management. However, we need more modelling and projection of what changes in landscape pattern are likely to emerge under this approach, along with long-term monitoring of places such as the Knepp Estate and Wild Ennerdale where it is being put into practice.

Pearl-bordered fritillary, Denbighshire.

Oak trees and Ennerdale lake.

Wild Ennerdale: Shaping the‘Future Natural’

Rachel Oakley

Everywhere you look there is hope; something blossoming, or growing, or recovering, or just being there in balance with nature.

Simon Webb,

Natural England and Wild Ennerdale

Hope is essential for anyone involved in nurturing our landscapes. Channelling that optimism into delivering real change takes an open mind, patience, courage and resilience. Multiply that among a group of people to make things happen and that energy can be a powerful tool and reap great rewards for a place.

Ennerdale allows us to nurture aspirations. It has a unique beauty within the Lake District landscape where forest, rivers, lakes, mountains, woodland, wildlife and people combine to give a sense of nature being in charge. It’s a landscape that’s seen the ebb and flow of human activity for thousands of years and is far from being ecologically pristine.

In the late 1990s, discussions started about how to do things a little differently in Ennerdale, triggered by the changing economics of commercial forestry and farming, along with a new staff member for National Trust. Wild Ennerdale began as a concept in 2003, establishing both a partnership and a set of guiding principles. The partnership brought together the three largest landowners with the principal aims of working at a landscape scale (covering 4,700 ha) with more freedom for natural processes. Key to the vision was people:

To allow the evolution of Ennerdale as a wild valley for the benefit of people, relying more on natural processes to shape its landscape and ecology.

Over the last two decades we have engaged with many different audiences and advocates, from local school children to key government advisors. Each experience is different and a learning opportunity for us. What is consistent is that we need to continue with what we are doing and do more of it – for nature’s sake and our own. The benefits of connecting with nature for health and well-being are well documented. We are learning, too, how nature can deliver more for us through better functioning ecosystems. This was most apparent when Storm Desmond hit Cumbria in 2015 and had a devastating impact on many communities. The clean-up in the aftermath at Ennerdale was negligible, while around the county the recovery remains ongoing, with millions of pounds spent on rebuilding visitor infrastructure and flood defences.

Natural processes are a key driver for our ambition. It’s a term we can now illustrate through practical delivery. While our starting point isn’t ‘ecologically pure’, there are processes at work which we can facilitate through more (or sometimes less) intervention to evolve from one state to another.

A shift away from Sitka spruce is one example and none have been planted within the last decade. While the existing non-native spruce will always be a part of the Ennerdale landscape (and indeed tell a story of its industrial past), there are now more broadleaf species of oak, rowan, alder, holly, aspen and birch, along with thousands of juniper. Many have been actively planted by volunteers and contractors. In other parts of the valley, trees are flourishing naturally from seed, aided by grazing Galloway cattle. A small herd of nine cows was introduced in 2006 and now graze extensively (about 40 cattle) over 1,000 ha of the valley. These hardy cattle, combined with a reduction in sheep numbers, are changing the farmed landscape. Simply having a more varied forest with scrubby ground vegetation of species offering depth, structure, colour, shelter and habitat – along with a large herbivore grazing and disturbing within – is an achievement in itself. Harsh boundaries between farmland and forest are starting to blur and new habitats are expanding and recovering upslope beyond existing treelines.

Cladonia lichen with red fruiting bodies.

The River Liza is a formidable force within the valley. It’s rare in a Lake District context, having the freedom to function naturally along its entire length: from its source at the valley head, through the heart of the middle valley to the lake at Ennerdale Water. It asserts its route with dynamism and energy and has space to connect to its floodplain. The obvious benefits this river delivers is inspiring to observe, particularly after high-rainfall events, with the majority of debris shifted and deposited in the upper valley, well away from the lake downstream and communities beyond. Large boulders, gravels, silts, scrubby vegetation, trees (all shapes and sizes) are on a journey of destruction and creation within a constantly changing river system. In terms of intervention it needs very little, but that in itself is active management. Where existing barriers did exist (such as a concrete ford in a tributary to the Liza), we’ve removed them. This aided the natural flow of that mountain tributary into the Liza along with the gravels and vegetation it carries. It has also opened up 5 km of new spawning habitat for migrating fish. Along the riparian corridor, the reintroduced marsh fritillary butterfly is now thriving, as wetlands increase and the host plant devil’s bit scabious is plentiful.

Whatever we do in the valley and wherever we do it, the impacts of our actions are considered across the whole landscape. It’s a balancing act on a big scale, where people and nature are so intrinsically linked that they shouldn’t be viewed as separate entities, but rather as processes working more in harmony to encourage a more diverse, healthy and resilient landscape into the future.

Rewilding should be challenging, but not at the expense of action. It is the responsibility of all those of us involved in helping to look after the land to ensure our actions are suited to that unique location, understand our starting point and to tailor different approaches accordingly. By engaging people along that journey, whether advocates or critics, the ambition can become a reality and whatever uncertainties lie ahead, there’s optimism that we are on the right track.

Little boy in an Epping den.

Epping Forest: A Wildwood?

Judith Adams

‘Whoever looks around sees eternity here’

John Clare

A fragment of the Royal Forest of Essex, dating from around 1100 ce, Epping Forest is London’s largest open space of 2,500 ha, supporting the largest number of veteran trees (50,000) of any site in Europe. Crescent in shape, it stretches from East London’s Manor Park to Epping in the County of Essex. It provides a playground for Londoners and the northern part in particular, largely from Chingford northwards, is London’s ‘wildwood’.

The Epping Forest Acts of 1878 (and 1882) brought the remaining forest land into the guardianship of the City of London as conservators, securing its protection as a public open space for the recreation and enjoyment of the public – while also preserving its ‘natural aspect’. It is the first protected conservation area in the UK. Some 70% is now designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, with most of that also a Special Area for Conservation. A Green Heritage and Green Flag site and part of the Royal Commonwealth Canopy, it has over 4.4 million visits a year. It continues to be managed by the City of London.

Considering its earlier history, from establishment as a Royal Forest in Norman times, the use and perceived value of the forest has changed. Forest law protected the rights of the King for its use as a hunting forest. The Forest Charter of 1217 gave commoners (freemen only) rights of grazing, cutting of wood and allowing pigs to forage, establishing what we now identify as wood pasture.

As the significance of the Forest laws declined, the Lords of the Manor played a greater part and, particularly from the mid-1700s, forest land was lost through enclosure – some land taken as parklands for great houses and, later, many acres accommodated the expansion of London. Lopping continued on the forest wastes, but as railways developed and coal became available, lopping declined. After the 1878 Forest Act withdrew lopping rights, lopping only operated in the Parish of Loughton in the more northern part of the forest.

The Victorian period saw the advent of public holidays and tram and rail access to the forest, and the development of recreation, including donkey rides, picnics and outings by pubs, workhouses, churches and workplaces. Golf and cricket began to be played too along with the growth of retreats and large tea houses. Since the early 1970’s, schools have visited the forest, supported by the FSC, to undertake field studies and research, along with an increasing number of academics.

Given the forest’s high conservation status and its ever-increasing popularity as a place of recreation, the challenges are great.

The current focus of conservation management, largely in the northern part of the forest, has been to re-establish a more open ‘wood pasture’ habitat – protecting and increasing the longevity of the veteran trees and creating new pollards. This work aims to support and nurture the rich biodiversity associated with these ancient trees and the more open ground and scrub layer flora and fauna associated with grazing – both historic features of forest management/exploitation.

This has involved significant areas of felling/clearance; mainly silver birch and holly, along with some beech and hornbeam and the reintroduction of grazing. Of key concern is the absence of ‘middle age pollards’ that would provide habitat to accommodate the invertebrate and fungal communities associated with the veteran trees, which now have a reduced lifespan. Will the younger pollards, even with the use of veteranisation techniques (whereby younger trees are ‘damaged’ in a way which can speed up the process of production of valuable habitats), be able to support these communities?

As the focus currently is to recreate a past management regime in a new time, rewilding has no place here. The threat to the biodiversity, still in evidence from the historic land management would too great to give consideration to rewilding. It is similar to our remaining chalk grasslands, where grazing is being reintroduced to ensure the future of these species-rich grasslands.

But what of its wildness? H. L. Edlin, in Trees Woods and Man (Colllins New Naturalist, 1956), expressed great relief that pollarding had stopped: ‘Lopping has ceased, and at last Epping trees of natural form are being allowed to succeed the sorry, grotesque pollards as they gradually decay, so that eventually there will arise a forest of real grandeur.’

Ancient beech pollards in mist.

What we see now are veteran pollards of real grandeur – celebrated by artists, photographs and our visitors. We too, like the poet John Clare, can experience eternity in the forest – it lifts hearts and provides solace in times of trouble and lies just 12 miles east of St Paul’s.

The recent work to restore wood pasture management is changing the forest again, in some areas making it more difficult to get ‘lost’ in the forest.

So how should this be addressed and does it matter? Wood pasture restoration is designed to secure a future for the rich biodiversity. We don’t have a great understanding of exactly what the forest was like over the centuries and how it varied in various manors of the forest over time, from the more productive areas on London clay, to the acid rich soils where the pollarded beech are more common. There is the risk that the increasingly open forest will over-facilitate access to the forest, including mountain bikes, placing the fragile soils and the trees at risk. There are questions around how the current approach will fare in an area with multifunctional use, increasing population and in a period of climate change. Is it sustainable?

What of the ‘natural aspect’, enshrined in the Act? What will become of it in the future? Will future generations love, value and warm to this wonderful area of Epping Forest? And will it still seem wild?

These are questions that can only be answered by those who follow us. It is so important to work tirelessly to preserve the biodiversity associated with ancient trees. There is an ongoing need for research both of the habitats and species, along with historical studies – what was it really like in past times? And of course, a need, too, for an ongoing assessment of the value of our efforts.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.