Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

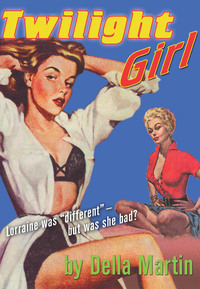

Kitabı oku: «Twilight Girl»

THE IN-BETWEEN SEX

“You remember that girl, right here at this bar?”

“Oh, yes.”

“You bet me a quarter I couldn’t make her.”

“You didn’t.”

“Oh, didn’t I?”

“I’ll be damned.”

“I’ve got a witness.” The first of them turned to the silent one. “Did I make her, Chuck?”

“If you don’t know, I’m not gonna tell you,”

They roared at this and then the loser paid her bill. “Here’s your goddam quarter. Just tell me one thing. Was she butch or fern?”

“Smorgasbord. By the time she went home I wasn’t sure which I was!” Eyebrows wriggled up and down, implying secrets that could not be unveiled. Regular guys, remembering a girl and laughing it up. Regular guys, flicking kitchen matches with their thumbnails for a light, burrowing hands in the front-zipped pants for a crushed cigarette pack and belting each other in the back to punctuate a bellylaugh. Regular guys, and less than twenty years before, unknowing nurses had checked the wrong box on the hospital form that offered only Male and Female. For perhaps the choice was incomplete …

Twilight Girl

Della Martin

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

Or simply visit

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

Table of Contents

Cover

The In-Between Sex

Title Page

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Part Two

8

9

10

Part Three

11

12

13

14

15

Endpages

Copyright

Part One

Kid Stuff

1

IT WAS on the day Lon Harris decided to spare the mutt that she met the girl with the violet hair. In the psychiatrically charted years to come, Lon might occasionally pause to reflect upon this fact, searching the seemingly fortuitous occurences for some suggestion of ironic pattern—speculating, perhaps, on the alternate courses her life might have taken if:

(1) Miss Chamberlin’s dog had eaten the greasy mound of hamburger, liberally loaded with the pulverized remains of a 7-Up bottle, and

(2) If Lon had not made the acquaintance of a shapely car-hop whose name, translated from Czech, meant Violet Soup.

But throughout that day in mid-June—the last day of school—Lon Harris lacked the composure for musing on the vagaries of fate. She did, as she had always done, the things it occurred to her to do.

English III was Lon’s final period. Today it amounted to no more than a tension-charged killing of time for the Wellington High junior class. Books had been turned in on the previous morning and Miss Chamberlin staved off the mounting restlessness by inviting the students to discuss their plans for the summer. Listening to this recital, Lon was tremulous, her eyes chained to the wall clock. She was longing for and yet dreading the electric bell that would eject her, perhaps forever, from the warm presence of Netta Chamberlin. Waiting, Lon listened impatiently to the self-conscious voices.

HELEN LANG: I’m going to Oregon with my folks for three weeks. We’ve got this darling aqua trailer that just matches our car and it’ll be my first time out of California.

And, waiting, Lon wondered. Had Miss Chamberlin read the note? Read the revealing words? Yes, she had read it, she must have read it. But what would she say? When this hour was ended, what would she say?

RALPH ALVAREZ: My uncle got a body shop in San Fernando. I’ll be workin’ there if he don’t can me.

I held it in the palm of my hand all during class yesterday, Lon thought. Held it so tight that maybe the paper soaked up sweat—maybe the ink ran. And I held back to let everyone out of the room before me, so I could drop it unseen on her desk. But, oh, God, what if it was too blurry to read?

MARGIE McCANN: Oh, just horse around, I guess. Go to the beach. I don’t know.

Waiting and remembering, that’s what Lon was doing. Seeing the words as she hoped Netta Chamberlin had seen them: I am putting my innermost thoughts down because I know you feel the same way. (The last six words scratched out for a more impressive phrase.) I am cognizant of the fact that we share the same deep emotions and I have a plan whereby we can be together that I must tell you about. (The tiny slip of paper running out then, with still so much unsaid!) I would die if this was the last time I saw you. With all my love, Lon Harris. (Squeezing the last words uphill into the margin.)

DAN OSTERMAIER: Summer school. No comment!

Scattered applause, laughter. Then the switch-blade shrillness of the bell, the casual goodbyes, the cries of “This is it!” and, “Ye-ay-y!” The world that was not her world stampeded for the door and Lon lingered, paralyzed with the fearful hope.

“Lorraine?”

Eyes magnetized to the asphalt tile floor. “Yes, Miss Chamberlin?”

“I know you’re anxious to go, but you can spare a minute, can’t you?”

“It’s all right. Sure.”

“I’m a bit puzzled, Lorraine.”

“You are?”

“By your note.”

“Oh, that.”

“Of course, they’re quite common. Crushes on teachers. Or can we call it that, Lorraine?”

All the wrong words. Lon had rehearsed the dialogue carefully, ready with impassioned responses to cue lines that failed in this moment to come. Shame and regret bore down from the ecru walls, weighing her with an uncomprehended guilt. “I don’t know.”

“I don’t want to upset you, but as we grow older, Lorraine, we outgrow these impulses. I’ve always thought of you as level-headed and mature for your years. You read a lot, don’t you?”

“Quite a bit.”

“What do you like to read?”

“Oh—poetry. Books about the islands. I read just about anything.”

“Do you spend most of your time this way? Alone? Reading?”

“Well, I have a part-time job. Saturdays. This summer I might get to work weekdays, too.”

“Baby-sitting, I suppose?”

A rankling accusation. “No. I work at the pet shop. Washing dogs.”

“Do you have a lot of friends? Close friends?”

“I get along with the kids all right.”

“Boys, too?”

“I get along with them, too.”

“But no special boy?”

“I used to play ball a lot with Bud Schaeffer. Baseball. I used to get along great with him.”

“But you don’t play baseball now?”

Stupid questions, getting more senseless by the minute! “Who with? That was a long time ago.”

“Yes, and I suppose he’s like other boys. Busy working on his car … dating girls …”

“He doesn’t know the first thing about cars. I wouldn’t let him change the oil in my Plymouth. I washed a lot of flea-taxis to pay for that car. Well, the down payment and my dad gave me the rest, I mean. It’s old, but I take good care of it.”

“I don’t know how to put this, Lorraine. I seem to be saying everything badly. But what I’m trying to tell you is that when a girl gets to be … What are you, sixteen? Seventeen?”

“Sixteen.”

“She’s usually thinking about clothes and dates. Working on a jalopy is … uh … writing a sentimental, almost unnatural note such as the one you left for me yesterday …”

“That was just a silly thing. I forgot all about it.”

“I hope you did forget it, Lorraine. A note such as yours might be misinterpreted.” From out of her grab-bag of meaningless phrases, Miss Chamberlin pulled another. “I’m a woman, Lorraine. I’m thirty-two years old and unmarried. People … If someone read what you wrote to me, they might misunderstand.” And in a tone that implied deep significance where Lon sensed only absurdity, “I live alone, you see.”

“I know.”

“You really do know. You actually know?”

“You live in one of Hardesty’s duplexes. The ones with the fenced yard on Orange Grove.”

“You went out of your way to find out personal details about my life?” There was dismay and disapproval in the question. Wasn’t it enough that she hadn’t said the things she was supposed to say? Did she have to make inane statements and then act shocked at the obvious answers? Lon lifted her eyes to the doorway, yearning.

“Lorraine, I appreciate your … I’m glad, that is, that you like me and that you’ve enjoyed this semester in my class. I’m hoping you’ll find outlets that are more—shall we say, normal? You’re a very attractive girl. Your hair’s naturally wavy, isn’t it?”

“That’s from cutting it a lot. I like it short.”

“I’d like to see you walk more gracefully. Why, a girl as slim and tall as you are could be a model. Surely you must have some fondness for pretty clothes?”

Lon tugged at her brown wool sweater-vest. Shut up! Just shut up and let me go! Oh, let me go!

“With dark brown hair, you can get away with wearing lovely colors. Coral pink, for instance. You don’t want to look drab, Lorraine. Boys might find you very attractive if you set out a program for yourself and …”

“Is that all you wanted to tell me?”

“I suppose so. And I think you understand me. Do you, Lorraine?”

“I guess so.”

“Then you don’t think I’m saying these things to be critical? We’re still friends?”

“I have to drive a couple of kids home,” Lon lied. “They’ll think I ditched them.”

“Yes. Well, you run along, Lorraine.” And, strangely confused, Lon thought, for one who had guided the whole conversation, “But you do understand about writing notes to … And about boys. You do understand what I mean?”

“Sure. I’ll be seeing you, Miss Chamberlin.”

And she hurried into the joy-filled corridor where someone yelped, “T.G.T.I.F.!” and a chorus responded, “You know it! Thank God this is Friday—the last Friday!” She hurried along the dark, warm hall, scalding moisture clouding her vison of the marbled walls until she was in the students’ parking lot where the hot salt zigzag tears burned on her face. It began then; the thin trickle of sound that was not a sound within her head. It was deeper inside her body, where so much was compressed that could not be revealed, where the buried questions begged to be released. Not why am I unlike the others, but why are the others unlike me? And I want, I want, but what is it I want?

Some of the others sang now. Packed into cars and filled with the T.G.T.I.F. joy of singing:

Give a cheer, give a cheer,

For the boys who drink the beer,

In the cellars of Wellington High!

A raked Chevy screamed past her and the melody of the Caisson Song filled the dusty yard:

They are brave, they are bold,

And the liquor they can hold

Is the glory of Wellington High!

No one was waiting beside the beat-up Plymouth. No one waited for the gangling odd-ball with the hazel eyes, as no one had ever waited. Only the questions waited, as if in some seldom-dusted cobwebbed corner of her consciousness. And who would answer the questions? Who now? There were answers that some sphynx-like mother creature might know. Yet someone who, unmotherlike, would not advise, saying only, “This is why you ran to the bathroom and were sick when Bud Schaeffer touched your breast and kissed you; this is why you ache inside, running to the refuge of the Island, the secret you would have shared with the woman in English III; and this is why you trembled in tears and a violent gladness the afternoon her hand touched yours and she smiled—smiling, you were certain, for no one else.”

Lon pulled open the car door. Far down the street the bawling voices receded:

And it’s guzzle, guzzle, guzzle,

As it trickles down your muzzle,

And you hear them shout, “More beer!”

MORE BEER!

Lon turned the ignition key unsteadily, rammed an angry thumb against the starter button. Mother-creature, lover-creature, someone, someone! There had been someone, yet now no one was near. Now there was only the raging heat, the stinging pain of humiliation. That, and the thin minor wail, keen-edged. Transparent, quavering like her mother’s edgy voice, yet dimly reminiscent, too, of space movies; the weird humming tone that sets the scene for some remote planet, horribly beautiful, breathlessly strange. No one near, and the only other occupants of the old tan car were familiar traveling companions—grown monstrously huge on this eighteenth day in June—confusion, hunger, and the shameful anger born of their union.

Lon parked the Plymouth, stepped out of it, and walked into the house.

It might be that the elementary school PTA was hosting a farewell tea for the teachers. Or maybe, even, the Brotherhood Week Committee was meeting at the church. Maybe, even, the Civic Betterment unit of the Women’s Club was in session. Whatever the reason, Lon rejoiced. Her mother was not at home!

Wild, way out, crazy. No comments about the jeans Lon pulled on being belted too low. No shaking pronouncements about what people thought of a girl who tugged a red cotton T-shirt over her boyish chest and let it go at that. No queries about why Lon whacked a clod of half-frozen hamburger from a package in the refrigerator.

She took the ground meat to the open garage, laying it on the cement in a square of sunlight. Waiting for it to defrost, she knocked the neck off a 7-Up bottle with a hammer. Enjoying the process, she demolished the painted green bottle completely, pushing a few of the smaller pieces into an old leather glove. Then, breathing the short breaths of perverse excitement, the quick snatches of air that denote elation, she pounded the glove viciously with the hammer. When the glass was reduced to rough powder, she stuffed the hamburger inside the glove. She pounded meat and glass together under the leather binding. When the ingredients were one, she scooped the lethal mixture into a brown manila envelope, tossed the glove carelessly into a trash barrel, and returned, trembling with anticipated revenge, to the car.

It was not a long drive to her destination. She parked inconspicuously, sneaked even more inconspicuously to a point of vantage.

Watching Miss Chamberlin’s dog race the length of the redwood fence, Lon wondered if it were true. That business Mr. Beckwith had told her about Dalmatians. “Most other breeds can’t stand them. Other dogs just have it in ‘em to hate Dalmatians,” Saying it as though owning a stinking pet shop made him an authority. “It’s the color of their eyes,” he had explained sagely. And had added in an awesome voice, as though speaking the Great Hidden Wisdom, “And the spots!”

It was, Lon decided, a crock of the well-known article, hating herself immediately for borrowing her father’s army phrase.

“Here, boy!” she called.

The dog, falling all over his paws, hurling his black-flecked body in a convulsion of joy at being noticed, ran to the corner of the fence.

I’ll bet she’s crazy about this dog. Maybe she hasn’t got a friend in the world except this dog….

Forepaws on the inside wall of the board fence, the dog stretched his head upward for human contact. Lon patted the sleek, sun-warm head. Her other hand dangled the brown envelope against her knee.

It’ll crack her up to lose this beautiful dog. She won’t have anybody …

“Here, boy. Got something for you.”

The Dalmatian ducked his head, twisting it then into position to gnaw cautiously at her hand.

“You’re sure you like dogs?” Mr. Beckwith had asked before hiring her. “No use taking on somebody that don’t like dogs.”

“I love ‘em,” Lon had said.

“What kind you got?”

“Oh. Well, I don’t actually have one.”

“That’s a fine kettle of fish.” Peering at her suspiciously.

“No, y’see, my mother’s president of the Garden Club and we have all these begonias and junk around the yard. That’s the only reason.”

“Begonias!” He had spat the word across the counter. But hired her anyway. And taught her enough about dogs so that now she shuddered, knowing what would come—the twitching of flesh and agonized whine, the stomach walls grinding red and merciless in the cutting green dust, the eyes pleading silently …

Lon muzzled the dog’s face and roughed it back and forth. “Quit slobbering over me, stupid.” His tail whipped the air. “Big overgrown pup!” The Dalmatian shifted paws, scrambling against the fence. “Think you’re a lap dog, I’ll bet. Hey, you lonesome, pooch? All by yourself all day long? How come other dogs don’t like you?” Pushing his face and grinning at the fake growls. “You different? Is that why? That why the other dogs don’t like you?”

She grasped his paws firmly in one hand, then shoved him away from the fence and turned before he could resume the game.

A minute later she was back in the Plymouth.

Circling the neighboring blocks, as she had done so often before in the hope of catching a glimpse of Miss Chamberlin, Lon pondered the problem of what to do with the brown, grease-stained envelope. Throw it out the window and some other dog might get it.

At the corner of San Leandro Drive and Los Altos, she stopped the car. Climbing out, looking up and down the deodar-lined street, she dropped her package into the corner mailbox. When she heard the envelope hit the metal floor with a hollow thud, she leaped back into the Plymouth and drove home.

Lon said no more than was necessary during dinner, having learned that the shrill nasal whine of her mother’s voice would eventually wither from lack of response.

Mrs. Harris held a trembling fork in her hand, recounting the day’s events. “I told the girls, not one more committee! I’m swamped now, I told them. Supervising the Sunday School is a full-time job and don’t you think I’m not going to hold my ground.”

“And stick to your guns,” Lon’s father placated. “They expect too much of you.”

Long ago, Lon had concluded that Edwin Harris had been born for no ostensible purpose except to be agreeable. She had inherited her slim, angular body from him, but had been spared the myopic eyes that blinked at accounting sheets through thick horn-rimmed glasses by day and were the scourge of the Little League in the evenings. It was rare in the years since Eddie Junior had been born that she could bear to look at her father.

“When they find a good organizer, they work her to death,” Mrs. Harris said. “I told them that right to their faces.”

“Good for you,” encouraged the man behind the glasses.

“Verna had the gall to tell me I’ll have more time with the kids out of school. Came right out and asked me if Lon didn’t help around the house. Of course, what could I tell her?” Shaky hands left the table to pat the machine-frizzled hair. And the bright dark eyes turned accusingly toward Lon.

Lon counted frozen peas. And her father poured oil on the troubled waters. “Lon’s not like Evie and Judith. We’re all different, Mother.”

“She carried all the rocks.” This was an unexpected defense from the potato-stuffed mouth of Eddie Junior. “She brang the rocks for the rock garden.”

Lon threw him a wry thank-you with her eyes, sweeping in that moment the thin, simian face, wizened, somehow, far beyond its eight years. Mention of her sisters and the sight of Eddie’s face stirred the buried recollections, the unburied resentments. Evie and Judith, married now, but in those days primping and giggling and bossing her around the house, with no Eddie in view. And Dad tousling her hair, teasing, “Counted on you to play with Brooklyn, y’little monkey!” Never really complaining because she was a girl. Joking about it that way. Playful, controlled punches in the arm, full-swinging pats on the back when she stole third or scooped a playground grounder. And proud of her, with the pride nurturing, growing inside her.

And all this was B.E.—Before Eddie, the family afterthought who squealed, bleated, kicked and raged his protest vainly, ignored in his protests by Dad, who now had a son to be buddy to. For above all that was sacred, Eddie Harris Senior believed fervently in his mission as Father, the Pal. So that After Eddie, there came to Lon the life-vital need to be more a boy, more a pitcher, more, more—until the gentle swelling under the smudged T-shirt proclaimed the odds insurmountable, the competition too heartlessly stacked against her. So that now Dad had Eddie, and L.A., not Brooklyn, had the Dodgers. And Lon had the Island, discovered in reverie between her twelfth and thirteenth years—the undetermined pin-point in the Pacific to be peopled with a painstakingly selected population. Excluding the Harrises, one and all. Except Lon.

“People are noticing the way she runs around, Dad.” Her mother’s flute-pitched lecture on the state of the beltline of Lorraine Harris’s jeans was usually channeled through a neutral source. “You’d think if she has to dress like a hooligan, she could at least recognize where God put her waistline!”

The voice-sound blended with the whine in Lon’s head. Shut up! Just shut up and let me go.

“It could be worse.” Dad apologizing for her again. “She could be painting her face like a barn and staying out late with boys. Am I right, Lonnie?”

Lon nodded yes to the milk glass. And when it was over once more, she washed and dried the dishes mechanically, then closed the door of her room behind her.

The room, like the rest of the new gingerbread-tract house, was furnished in an abortive maple—rag-rug—pepper-grinder—lampbase attempt to resurrect old New England in new Los Angeles suburbia. But the Polynesian masks Lon had whittled from fallen dried palm fronds were her own. The draped fishnet and cork floats were hers. And the papers she took reverently from the bottom desk drawer belonged to a world that none other traveled, except by invitation of the fertile mind. Carefully she chose them, the residents of this unsurveyed microcosm of her fantasy.

She passed quickly over the world map, the South Pacific circled in red crayon and marked: In This General Area. Nor was there need, this evening, to review the List of Supplies (fish-hooks, canned milk, thread, pencils, paper)—some day to be alphabetically arranged, but scrawled now in green ink. And no time for the Sacred Rites of —— (name of Island to be selected when we arrive). No interest now in the Secret Incantations, lists, charts, schedules, village layouts, codes, rules, menus, constitution, cultural and recreational plans—or the notebook devoted to Ideas on How to Get There, including:

A. Boat (Check costs)

B. Where to Sail From

C. Knowledge of Sailing (Find someone who knows about it)

With none of these details was Lon Harris concerned on this evening of the last day of school in June. From the imposing sheaf of papers she pulled the list of proposed inhabitants. For reasons she had never considered, accepting the fact as casually as she chose a gray sweatshirt over an eyelet embroidered blouse, none of the names recorded was male. Under the heading LON HARRIS, HIGH PRIESTESS was another name she had added to the roll call early in the second Junior-year semester. With a surge of something inside her that had wavered before friendly Dalmatian eyes, she picked up a ballpoint pen and traced a question mark after SECOND HIGH PRIESTESS. Then grimly, her revenge tempered by the solemn responsibility of her ritual, she drew a line through the name of Netta Chamberlin. And in that moment, the sound in her head that was not a sound abruptly stopped.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.