Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

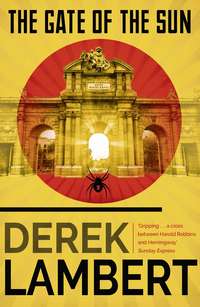

Kitabı oku: «The Gate of the Sun», sayfa 2

‘What you’ve got to do,’ Tom said, ‘is remember what we’re fighting for.’

‘I sometimes wonder.’

‘The atrocities …’

‘You mean our guys, the good guys, didn’t commit any?’

Tom was silent. He didn’t know.

‘In any case,’ Seidler said, ‘I’m supposed to be commiserating with you.’ He poured more brandy. ‘I hear that the Fascists have got a bunch of Fiat fighter planes with Italian crews. And that the Italians are going to launch an attack on Guadalajara.’

‘Where do you hear all these things?’

‘From the Russians,’ Seidler said.

‘You speak Russian?’

‘And Yiddish,’ Seidler said. The hut was suddenly suffused with pink light. ‘Here we go,’ Seidler said as the red alert flares burst over the field.

‘In this?’ Tom stared incredulously at the sleet.

They ran through the sleet which was, in fact, slackening – a luminous glow was now visible above the cloud – and climbed into the cockpits of their Polikarpovs. Tom knew that this time he really was going to war and he wished he understood why.

The Jarama is a mud-grey and thoughtful river that wanders south-east of Madrid in search of guidance. It had given its name to the battle being fought in the valley separating its guardian hills, their khaki flanks threaded in places with crystal, but in truth the fight was for the highway to Valencia which crosses the Jarama near Arganda. On this morose morning in February the Fascists dispatched an armada of Junkers 52s to bomb the bridge carrying this highway over the river.

Tom Canfield saw them spread in battle order, heavy with bombs, and above them he saw the Fiats, the Italians’ biplanes which Seidler had forecast would put in an appearance. He pointed and Seidler, flying beside him, peering through his prescription goggles, nodded and raised one thumb.

The Fiats were already peeling off to protect their pregnant charges and the wings were beating again in Tom Canfield’s chest. He gripped the control column tightly. ‘But what are you doing here?’ he asked himself. ‘Glory-seeking?’ Thank God he was scared. How could there be courage if there wasn’t fear? He waited for the signal from the squadron commander and, when it came, as the squadron scattered, he pulled gently and steadily on the column; soaring into the grey vault, he decided that the fear had left him. He was wrong.

The Fiat came at him from nowhere, hung on behind him. Bullets punctured the windshield. A Russian trainer had told him what to do if this happened. He had forgotten. He heard a chatter of gunfire. He looked behind. The Fiat was dropping away, butterflies of flame at the cowling. Seidler swept past, clenched fist raised. No pasarán! Seidler two, Canfield zero. He felt sick with failure. He kicked the rudder pedal and banked sharply, turning his attention to the bombers intent on starving Madrid to death.

Below lay the small town of San Martín de la Vega, set among the coils of the river and the ruler-straight line of a canal. He saw ragged formations of troops but he couldn’t distinguish friend from foe.

The anti-aircraft fire had stopped – the deadly German 88 mm guns could hit one of their own in this crowded sky – and the fighters dived and banked and darted like mosquitoes on a summer evening.

Tom saw a Fiat biplane with the Fascist yoke and arrows on its fuselage diving on a Polikarpov. As it crossed his sights he pressed the firing button of his machine-guns. His little rat shuddered. The Fiat’s dive steepened. Tom watched it. He bit the inside of his lip. The dive steepened. The Fiat buried its nose in a field of vines, its tail protruding from the dark soil. Then it exploded.

Tom was bewildered and exultant. And now, above a hill covered with umbrella pine, he was hunting, wanting to shoot, wasting bullets as the Fiats escaped from his sights. So close were they that it seemed that, if the moments had been frozen, he could have reached out and shaken the hands of the enemy pilots. But it had been a mistake to try and get under the bombers; instead he attacked them from the side. He picked out one, a straggler at the rear of his formation. A machine-gun opened up from the windows where Seidler had imagined passengers staring at him; he flew directly at the gun-snarling fuselage, fired two bursts and banked. The Junkers began to settle; a few moments later black smoke streamed from one of its engines; it settled lower as though landing, then, as it began to roll, two figures jumped from the door in the fuselage. The Junkers, relieved of their weight, turned, belly up, turned again, then fell flaming to the ground. Parachutes blossomed above the two figures.

Without looking down he saw again the white, naked faces of Spaniards killing each other, and reminded himself that among them were Americans and Italians and British and Russians, and wondered if the Spaniards really wanted the foreigners there, if they would not prefer to settle their grievances their own way, and then a Fiat came in from a pool of sunlight in the cloud and raked his rat from its gun-whiskered nose to its brilliant tail.

The Polikarpov was a limb with severed tendons. Tom pulled the control column. Nothing. He kicked the rudder pedal. Nothing. Not even the landing flaps responded. One of his arms was useless, too; it didn’t hurt but it floated numbly beside him and he knew that it had been hit. The propeller feathered and stopped and the rat began its descent. With his good hand Tom tried to work the undercarriage hand-crank, but that didn’t work either. Leafless treetops fled behind him; he saw faces and gun muzzles and the wet lines of ploughed soil.

He pulled again on the column and there might have been a slight response, he couldn’t be sure. He saw the glint of crystal in the hills above him; he saw the white wall of a farmhouse rushing at him.

CHAPTER 2

Ana Gomez was young and strong and black-haired and, in her way, beautiful but there was a sorrow in her life and that sorrow was her husband.

The trouble with Jesús Gomez was that he did not want to go to war, and when she marched to the barricades carrying a banner and singing defiant songs she often wondered how she had come to marry a man with the spine of a jellyfish.

Yet when she returned home to their shanty in the Tetuan district of Madrid, and found that he had foraged for bread and olive oil and beans and made thick soup she felt tenderness melt within her. This irritated her, too.

But it was his gentleness that had attracted her in the first place. He had come to Madrid from Segovia because it had called him, as it calls so many, and he worked as a cleaner in a museum filled with ceramics and when he wasn’t sweeping or delicately dusting or courting her with smouldering but discreet application he wrote poetry which, shyly, he sometimes showed her. So different was he from the strutting young men in her barrio that she became at first curious and then intrigued, and then captivated.

She worked at that time as a chambermaid in a tall and melancholy hotel near the Puerta del Sol, the plaza shaped like a half moon that is the centre of Madrid and, arguably, Spain. The hotel was full of echoes and memories, potted ferns and brass fittings worn thin by lingering hands; the floor tiles were black and white and footsteps rang on them briefly before losing themselves in the pervading somnolence.

Ana, who was paid 10 pesetas a day, and frequently underpaid because times were hard, was arguing with the manager about a lightweight wage packet when Jesús Gomez arrived with a message from the curator of the museum who wanted accommodation for a party of ceramic experts in the hotel. Jesús listened to the altercation, and was waiting outside the hotel when Ana left half an hour later.

He gallantly walked beside her and sat with her at a table outside one of the covered arcades encompassing the cobblestones of the Plaza Mayor and bought two coffees served in crushed ice.

‘I admired the way you stood up to that old buzzard,’ he said. He smiled a sad smile and she noticed how thin he was and how the sunlight found gold flecks in his brown eyes. Despite the heat of the August day he wore a dark suit, a little baggy at the knees, and a thin, striped tie and a cream shirt with frayed cuffs.

‘I lost just the same,’ she said, beginning to warm to him. She admired his gentle persistence; there was hidden strength there which the boy to whom she was tacitly betrothed, the son of a friend of her father’s, did not possess. How could you admire someone who pretended to be drunk when he was still sober?

‘You should ask for more money, not complain that you have been paid less.’

‘Then I would be sacked.’

‘Then you should complain to the authorities and there would be a strike in all the hotels and a general strike in Madrid. We shall be a republic soon,’ said Jesús, giving the impression that he knew of a conspiracy or two.

Much later she remembered those words uttered in the Plaza Mayor that summer day when General Miguel Primo de Rivera still ruled and Alfonso XIII reigned; how much they had impressed her, too young even at the age of 22 to recognize them for what they were.

‘My father says we will not be any better off as a republic than we are now.’ She sucked iced coffee through a straw. How many centimos had it cost him in this grand place? she wondered.

‘Then your father is a pessimist. The monarchy and the dictatorship will fall and the people will rule.’

On 14 April 1931, a republic was proclaimed. But then the Republicans, who wanted to give land to the peasants and Catalonia to the Catalans and a living wage to the workers and education to everyone, fell out among themselves and, in November 1933, the Old Guard, rallied by a Catholic rabble-rouser, José Maria Gil Robles, returned to power. Two black years of repression followed and a revolt by miners in Asturias in the north was savagely crushed by a young general named Francisco Franco.

But at first, in the late 20s, before Primo de Rivera quit and the King fled, Ana and Jesús Gomez were so absorbed in each other that, despite the heady predictions of Jesús, they paid little heed to the fuses burning below the surface of Spain; in fact it wasn’t until 1936 that Ana discovered her hatred for Fascists, employers, priests, anyone who stood in her way.

When Jesús proposed marriage Ana accepted, ignoring the questions that occasionally nudged her when she lay awake beside her two sisters in the pinched house at the end of a rutted lane near the Rastro, the flea-market. Why after nearly a year was he still earning a pittance in the perpetual twilight of the museum whereas she, at his behest, had demanded a two-peseta-a-day pay rise and been granted one by an astounded hotel manager? Why did he not try to publish the poems he wrote in exercise books? Why did he not join a trade union, because surely there was a place for a museum cleaner somewhere in the ranks of the CNT or UGT?

They were married during the fiesta of San Isidro, Madrid’s own saint. The ceremony, attended by a multitude of Ana’s family, and a handful of her fiancé’s from Segovia, was performed in a frugal church and cost 20 pesetas; the reception was held in a café between a tobacco factory and a foundling hospital owned by the father of Ana’s former boyfriend, Emilio, who fooled everyone by getting genuinely drunk on rough wine from La Mancha.

Emilio, whose black hair was as thick as fur, and who had been much chided by his companions for allowing the vivacious and wilful Ana to escape, accosted the bridegroom as he made his way with his bride to the old Ford T-saloon provided by Ana’s boss. He stuck out his hand.

‘I want to congratulate you,’ he said to Jesús. ‘And you know what that means to me.’ He wore a celluloid collar which chafed his thick neck and he eased one finger inside it to relieve the soreness.

Jesús accepted the handshake. ‘I do know what it means to you,’ he said. ‘And I’m grateful.’

‘How would you know what it means to me?’ Emilio tightened his grip on the hand of Jesús, becoming red in the face, though whether this was from exertion or wine circulating in his veins was difficult to ascertain.

‘Obviously it must mean a lot,’ Jesús said, trying to withdraw his hand.

Ana, who had changed from her wedding gown into a lemon-yellow dress, waited, a dry excitement in her throat. The three of them were standing between the café where the guests were bunched and the Ford where the porter from the hotel stood holding the door open. No-man’s-land.

‘It means a lot to me,’ Emilio said thickly, ‘because Ana promised herself to me.’

‘Liar,’ Ana said.

‘Have you told him what we did together?’

‘We did nothing except hang around while you pretended to get drunk.’ What she had seen in Emilio she couldn’t imagine. Perhaps nothing: their union had been decided without any reference to her.

Emilio continued to grip the hand of Jesús, the colour in his cheeks spreading to his neck. Jesús had stopped trying to extricate his hand and their arms formed an incongruous union, but he showed no pain as Emilio squeezed harder.

The group outside the café stood frozen as though posing for a photographer who had lost himself inside his black drape.

‘We did a lot of things,’ Emilio grunted.

The porter from the hotel, who wore polished gaiters borrowed from a chauffeur and a grey cap with a shiny peak, moved the door of the Ford slowly back and forth. Fireworks crackled in the distance.

Jesús, thought Ana, will have to hit him with his left fist – a terrible thing to happen on this day of all days but what alternative did he have?

Jesús smiled. Smiled! This further aggrieved Emilio.

‘You would be surprised at the things we did,’ he said squeezing the hand of Jesús Gomez until the knuckles on his own fist shone white.

Finally Jesús, his smile broadening with the pleasure of one who recognizes a true friend, said, ‘Emilio, I accept your congratulations, you are a good man,’ and began to shake his imprisoned hand up and down.

‘Cabrón,’ Emilio said.

‘God go with you.’

‘Piss in your mother’s milk.’

‘Your day will come,’ Jesús said, a remark so enigmatic that it caused much debate among the other guests when they returned to their wine.

The two men stared at each other, hands rhythmically rising and falling, until finally Emilio released his grip and, massaging his knuckles, stared reproachfully at Jesús Gomez.

Jesús saluted, one finger to his forehead, turned, waved to the silent guests, proffered his arm to his bride and led her to the waiting Ford.

From the bathroom of the small hostal near the Caso de Campo, she said, ‘You handled that Emilio very well. He is a pig.’

She took the combs from her shining black hair and shed her clothes and looked at herself in the mirror. In the street outside a bonfire blazed and couples danced in its light. Would he ask her about those things that Emilio claimed they had done together?

‘Emilio’s not such a bad fellow,’ Jesús said from the sighing double bed. ‘He was drunk, that was his trouble.’

Didn’t he care?

‘He is a great womanizer,’ Ana said.

‘I can believe that.’

‘And a brawler.’

‘That too.’

She ran her hands over her breasts and felt the nipples stiffen. What would it be like? She knew it wouldn’t be like the smut that some of the married women in the barrio talked while their husbands drank and played dominoes, not like the Hollywood movies in which couples never shared a bed but nevertheless managed to produce freckled children who inevitably appeared at the breakfast table. She wished he had hit Emilio and she knew it was wrong to wish this.

In novels, the bride always puts on a nightdress before joining her husband in the nuptial bed. To Señora Ana Gomez that seemed to be a waste of time. She walked naked into the white-washed bedroom and when he saw her he pulled back the clean-smelling sheet; she saw that he, too, was naked and, for the first time, noticed the whippy muscles on his thin body, and in wonderment, and then in abandonment, she joined him and it was like nothing she had heard about or read about or anticipated.

It is true that Ana Gomez only encountered her hatred during the Civil War, but it must have been growing sturdily in the dark recesses of her soul to show its hand so vigorously.

When, slyly, was it conceived? In the black years, when one of her three brothers was beaten up by police, losing the sight of one eye, for rallying the dynamite-throwing miners of Asturias? When, at the age of 62, her father, a gravedigger, bowed by years of accommodating the dead, was sacked by the same priest who had married her to Jesús for taking home the dying flowers from a few graves? Or because the same fat-cheeked incumbent had declined to baptize her first-born, Rosana, because she had not attended mass regularly, although for a donation of 20 pesetas he would reconsider his decision … Ah, those black crows who stuffed the rich with education and starved the poor. Ana believed in God but considered him to be a bad employer.

As the hatred, unrecognized, fed upon itself. Ana noticed changes in her appearance. Her hair, pinned back with tortoiseshell combs, still shone with brushing, the olive skin of her face was still unlined and her body was still young, but there was a fierce quality in her expression that was beyond her years. She attributed this to the inadequacies of her husband.

Not that he was indolent or drunken or wayward. He cooked and scavenged and cleaned and Rosana and Pablo, who was one year old, loved him. But he cared only to exist, not to advance. Why did he not write his sonnets in blood and tears instead of pale ink? wondered Ana who, since the heady days of courtship and consummation, had begun to ask many questions. It was she who had found the shanty in Tetuan, it was she who had found him a job paying five pesetas a week more than the National Archaeological Museum. But his bean soup was still the finest in Madrid.

When the left wing, the Popular Front, once again dispatched the Old Guard five months before the Civil War, Ana understood perfectly why strikes and blood-letting swept the country. The prisoners released from jail wanted revenge; the peasants wanted land; the people wanted schools; the great congregation of Spain wanted God but not his priests. What she did not understand were the divisions within the Cause and, although she reacted indignantly as blue-shirted youths of the Falange, the Fascists, terrorized the streets of the capital, she still didn’t acknowledge the hatred that was reaching maturity within herself.

On May Day, when a general strike had been called, she left the children with her grandmother and, with Jesús, who accompanied her dutifully but unenthusiastically, and her younger brother, Antonio, marched down the broad paseo that bisects Madrid, in a procession rippling with a confusion of banners. One caught her eye: ANTI-FASCIST MILITIA: WORKING WOMEN AND PEASANT WOMEN – red on white – and the procession was heady with the chant of the Popular Front: ‘Proletarian Brothers Unite’. In the side streets armed police waited with horses and armoured cars.

Musicians strummed the Internationale on mandolins. Street vendors sold prints of Marx and Lenin, red stars and copies of a new anti-Fascist magazine dedicated to women. And indeed women marched tall as the widows of the miners from Asturias advanced down the promenade. The colours of the banners and costumes were confusing – blue and red seemed to adapt to any policy – and occasionally, among the clenched fists, a brave arm rose in the Fascist salute.

After the parade the hordes swarmed across Madrid, through the West Park and over the capital’s modest river, the Manzanares, to the Casa de Campo, a rolling pasture of rough grass before the countryside proper begins. There they planted themselves on the ground, boundaries defined by ropes or withering glances, released the whooping children and foraging babies, tore the newspapers from baskets of bread and ham and chorizo, passed the wine and bared their souls to the freedom that was soon to be theirs.

Ana pitched camp between a pine and a clump of yellow broom where you could see the ramparts of the city, the palace and the river below, and, to the north, the crumpled, snow-capped peaks of the Sierra de Guadarrama.

Her happiness as she relaxed among her people, her Madrileños, who were soon to have so much, was dispatched by her brother after his third draught of wine from the bota. As the jet, pink in the sunshine, died, he wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and said, ‘I have something to tell you both. A secret,’ although she knew from the pitch of his voice that its unveiling would not be an occasion for rejoicing.

Antonio, one year her junior, had always been her favourite brother. And he had remained so, even when he married above himself, got a job, thanks to his French father-in-law in the Credit Lyonnais where, with the help of the bank’s telephones, he also traded in perfume, and mixed with a bourgeois crowd. He was tall, with tight-curled, black hair, a sensuous mouth and a nimble brain; his cheeks often smelled of the cologne in which he traded.

‘I have joined the Falange,’ he said.

It was a bad joke; Ana didn’t even bother to smile. Jesus took the bota and directed a jet of wine down his throat.

‘I mean it,’ Antonio said.

‘I knew this wine was too strong; it has lent wings to your brains,’ Ana said.

‘I mean it, I tell you.’ His voice was rough with pride and shame.

There was silence beneath the pine tree. A diamond-shaped kite flew high in the blue sky and a bird of prey from the Sierra glided, wings flattened, above it.

Ana said, ‘These are your wife’s words. And her father’s.’

‘It is I who am talking,’ said Antonio.

‘You, a Fascist?’ Ana laughed.

‘You think that is funny? In six months time you will be weeping.’

‘When you are taken out and shot. Yes, then I will weep.’ She turned to Jesús but he had settled comfortably with his head on a clump of grass and was staring at the kite which dived and soared in the warm currents of air.

Antonio leaned forward, hands clenched round his knees; he had taken off his stylish jacket and she could see a pulse throbbing in his neck. She remembered him playing marbles in the baked mud outside their home and throwing a tantrum when he lost.

He said, ‘Please listen to me. It is for your sake that I am telling you this.’

‘Tell it to your wife.’

‘Listen, woman! This is a farce, can’t you see that? The Popular Front came to power because enemies joined forces. But they are already at blows. How can an Anarchist who believes that “every man should be his own government” collaborate with a Communist who wants a bureaucratic government? As soon as the war comes the Russians, the Communists, will start to take over. Do you want that?’

‘Who said anything about a war?’

‘There is no doubt about it,’ Antonio said lighting a cigarette. ‘Within months we will be at war with each other.’

‘Who will I fight against? A few empty-headed Fascists in blue shirts?’

‘Listen, my sister. We cannot sit back and watch Spain bleed to death. The strikes, the burnings, the murders, the rule of the mob.’ He stared at the black tobacco smouldering in his cigarette. ‘We have the army, we have the Church, we have the money, we have the friends …’

‘Friends?’

‘I hear things,’ said Antonio who had always been a conspirator. ‘And I tell you this: the days of the Republic are numbered.’

Jesús, eyes half closed, said, ‘I am sure everything will sort itself out.’ He had taken a notebook from his pocket and was writing in it with an indelible pencil.

‘You were a Socialist once,’ Ana said to Antonio.

‘And I was poor. If I had stayed a Socialist or a Communist or an Anarchist I would have stayed poor. How many uprisings have there been in the past 50 years? What we need is stability through strength!’

‘And who will give that to us?’ She took the bota from her husband, poured inspiration down her throat. Her brother a Fascist? What about their brother, the sight knocked out of one eye by a police truncheon? What about their father, sacked by a priest with a trough of gold beneath his church? What about the miners, with their homemade bombs, gunned down by the military? What about the peasant paid with the chaff of the landowners’ corn?

‘There are many good men waiting to take command.’

‘Of what?’

‘I have said enough,’ Antonio said.

Jesús, licking the pencil point, said, ‘Good sense will prevail. Spain has seen too much violence.’

‘Spain was fashioned by violence,’ Antonio said. ‘But now a time for peace is upon us. After the battle ahead,’ he said. ‘Join us. The fighting will be brief but while it rages you can take the children into the country.’

She stared at him in astonishment. ‘Have you truly lost your senses?’

‘Life will be hard for those who oppose us.’

‘Threats already? A time for peace is upon us?’

Jesús said, ‘The milk of mother Spain is blood.’ He wrote rapidly in his notebook.

Antonio poured more wine down his throat and stood up, hands on hips. ‘I have tried,’ he said. ‘For the sake of you and your husband and your children. If you change your mind let me know.’

‘Why ask me? Why not ask my husband?’

Antonio didn’t reply. He began to walk down the slope towards the Manzanares dividing the parkland from the heights of the city.

When he was 50 metres away from her she called to him. The diamond-shaped kite dived and struck the ground; the bird of prey turned and flapped its leisurely way towards the mountains.

‘What is it?’

He stood there, suspended between distant childhood, and adulthood.

She raised her arm, bunched her fist and shouted, ‘No pasarán!’

The militiamen came for the priest at dawn, a dangerous time in the lawless streets of Madrid in the summer of 1936. Failing to find him, they turned on his church.

The studded doors gave before the fourth assault with a sawn-off telegraph pole. Christ on his altar went next, battered from the cross with the butt of an ancient rifle. They tore a saint and a madonna from two side chapels and trampled on them; they dragged curtains and pews into the street outside and made a pyre of them; they smashed the stained-glass window which had shed liquid colours on the altar as Ana and Jesus stood before the plump priest at their wedding. They were at war, these militiamen in blue overalls, some stripped to the waist, and a terrible exaltation was upon them.

Ana, who knew where the priest was, watched from the gaping doors and could not find it in herself to blame the wild men who were discharging the accumulated hatred of decades. Since the Fascist rising on July 17 the ‘Irresponsibles’ in the Republican ranks had butchered thousands and invariably it was the clergy who were dispatched first. Ana had heard terrible tales; of a priest who had been scourged and crowned with thorns, given vinegar to drink and then shot; of the exhumed bodies of nuns exhibited in Barcelona; of the severed ear of a cleric tossed to a crowd after he had been gored to death in a bullring.

But although she understood – the flowers that her father had taken from the graves of the privileged had been almost dead – such happenings sickened her and she could not allow them to happen to the priest hiding in the vault of the church with the gold and silver plate.

The leader of the gang, the Red Tigers, shouted, ‘If we cannot find the priest then we shall burn the house of his boss.’ He had the starved features of a fanatic; his eyes were bloodshot and his breath smelled of altar wine.

Ana, to whom blasphemy did not come easily, said, ‘What good will that do, burro, burning God’s house?’

‘He has many houses,’ the leader said. ‘Like all Fascists.’ He thrust a can of gasoline into the hand of a bare-chested militiaman who began to splash it on the walls. ‘What has God ever done for us?’

‘He did you no harm, Federico. You have not done so badly with your olive oil. How much was it per litre before the uprising?’

He advanced upon her angrily but spoke quietly so that no one else could hear him. ‘Shut your mouth, woman. Do you want that scribbling husband of yours shot for collaborating with the Fascists?’

‘As if he would collaborate with anyone. No one would believe you. They would think you were trying to take his place in my bed.’

‘The olive oil,’ the leader said more loudly, ‘is 30 centimos a litre. Who can say fairer than that?’

‘I asked what it was.’

‘So you know where the priest is?’ he shouted as though she had confessed and the militiamen paused in their pillaging and looked at her curiously.

She stared into the nave of the church where, with her parents and her brothers, she had prayed for a decent world and a reprieve for a stray alley cat and for her grandfather whose lungs played music when he breathed. She remembered the boredom of devotion and the giggles that sometimes squeezed past her lips and the decency of it all. She stepped back so that she could see the blue dome. A militiaman attacking a confessional with an axe shouted. ‘Do you know where the priest is, Ana Gomez?’

And it was then that Ana Gomez was visited by a vision of herself: one fist clenched, head held high, the fierceness that had been in gestation delivered. She told Federico to drag a pew from the pile in the street and when, grumbling, he obeyed, she stood on it.

She said, ‘Yes, I do know where the priest is,’ and before they could protest she held up one hand. ‘Hear me, then do what you will.’