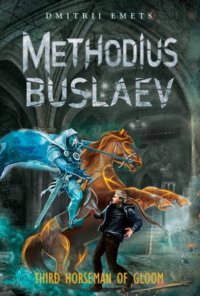

Kitabı oku: «Methodius Buslaev. Third Horseman Of Gloom», sayfa 3

Daph already wanted to leave the arch when she suddenly saw a dark spot on the asphalt. She squatted and ran her finger along it. She lifted her finger to her eyes and suddenly felt sick, nauseous, and horrible. To a guard of Light, even inexperienced, it was enough to see blood once in order to understand whose and under what circumstances the blow was inflicted. There was only one thing Daph could not say: who had inflicted it.

Chapter 2

AH YOU @ AND THE OTHER BEASTS

On noticing that the edge of the blanket had slipped, Irka straightened it. She preferred to keep her legs covered, even in summer, when there was no necessity for this. This way, sometimes it was possible to forget about their existence for a while. But during a massage, changing, or when she was taking a bath, she could not manage to run away from her legs, and they persistently tormented her gaze and soul – deprived of muscles, blue-white, with protruding knees that could bend only in the hands of the masseur.

How she hated her body: hideous, useless! How she wanted to break free and exist independently, out of the flesh. How she envied apparitions and ghosts, which freely moved in space, not depending on a body. Let alone that they did not need a wheelchair. And they did not have blue ghastly legs.

Over time Irka adjusted and more and more perceived her body as a small house of little boxes, the shell of a snail, on the whole, something serving as the temporary abode of the mind. Her legs, though, were a nuisance, a huge dinosaur tail that she had to drag behind her, when she, using the handrails attached to the walls, moved from the wheelchair to the bed or settled down in the armchair by the computer.

Now and then, after staying up reading or near the monitor until the middle of the night – Granny did not insist too much on a routine, she simply did not care for it – Irka became so tired that she almost existed out of her body. In any case, she hardly thought about it.

“The computer lights burn so terribly at night. Like Vii’s eyes,” she thought, falling asleep, although, it goes without saying, she personally was not acquainted with the reputable functionary from Bald Mountain.

All day she was reading – the pyramid of books occasionally grew to the middle of a wheel of the wheelchair and even higher. Her world was fantasy – hundreds of realities, sometimes terrible, sometimes tempting, sometimes strictly Gothic, in muted tacit colours. But all of them, even the most lacklustre, were still better than reality. As a result, Irka spent a large part of her life in dreams. She knew as much about dragons, centaurs, griffins, chimeras, the sharpening of swords, and the mechanism of crossbows, as only a person not having seen or held one can know. Under the assumption, of course, that all this was the minimum amount known by the authors of the books from which she got the information.

School did not especially strain her, since Irka studied as an external student. Helping her were her grandmother (mainly serving as a morally determined baton) and two teachers, with whom she met five or six times a month. Each year, lessons took up less and less time. At times, Irka wondered whether it was worthwhile for her to glance in a textbook, as she already knew the answer in advance. Everything was simple, logical and… boring. The most depressing of all was to write in the notebook even answers clear to her: to spell out in simple terms the elementary component, all these parentheses, degrees, intermediate actions, and other crutches of thought; to reveal formulae, where her mind leapfrogged two or three steps. In the end, tired of following dreary school conventions, Irka abandoned the tedious entries and limited herself to immediately writing the answer.

The first time, the teachers were indignant, claiming that she peeked into the “answer keys” and, according to Irka’s expression, “bread crumbs”. However, this continued only until she solved one of two dozen problems in their presence. Then the teachers stopped squealing in amazement, and in their eyes appeared the bewilderment of people who do not want to relinquish profitable tutoring; but deep down they wondered what was still possible to be taught here.

Irka had already passed exams for grade nine. Two more grades, swallowed by the external student, and it would be possible to enter college. But Irka was not particularly in a hurry. Intuition suggested that seventeen- or eighteen-year-old fellow students would not take her seriously but only as an amusing little talking pet. If so, then her student life, let it even be restricted in a wheelchair, would be hopelessly shattered.

This evening, when Granny, yawning in her shop, was cutting a marshal’s uniform for the theatre, Irka was home alone. And, it goes without saying, she was sitting in front of the computer. Irka’s computers – both the desktop and laptop – were on even at night and, as often happened, they frightened Granny with the sounds of texting.

Suddenly a strange sound was heard from the kitchen. A chair had fallen. Plates clattered. The teapot stand hanging from a cord also shook, scratching the wall. And in the next instant, it seemed to Irka that she heard a moan. Completely real. Human.

As any computer person, Irka thought with her fingers and was also scared with her fingers. Now, before panicking in earnest and sounding the alarm, she reflexively typed:

Rikka: Someone has gotten into our kitchen!

Anika-voin: Aha! They want to steal your antique fridge!

Miu-miu: run for help, but stop to make a sandwich on the way.

Rikka: I’m serious! Someone is moaning in there!

Miu-miu: eat a sandwich.

Anika-voin: What if some bozo came to you with a chainsaw? I wonder, do-chainsaws work not plugged in?

Miu-miu: Nah, hardly!

Rikka: Idiots!

While she was typing “Idiots!”, the moan in the kitchen repeated itself. The reality of what was happening finally reached Irka’s consciousness. And she actually felt fear. After all, the second floor is not the ninth. Granny had warned many times that a thief could climb in from the street, and if not a thief, then some tipsy cadre, who took it into his head to drink water from a tap.

And here this happened. Irka understood that she was sitting by the computer without light, and in that case, thieves could think that there was no one in the apartment. The kitchen had been quiet for a long time, but Irka, with some real, natural intuition, sensed that this was a false silence. There, in the dark, unlit kitchen, someone was lurking, someone completely real. She started to phone her grandma on the cell phone, but Granny did not answer. Her workshop was in a semi-basement with such thick walls that a cell phone only picked up when she by chance appeared near the window.

After deciding that the most reasonable thing would be to go to the neighbours, Irka began to quickly turn the wheels of her wheelchair, but the monitor continuously flared up, spitting out new lines.

Anika-voin: Hey, what’s with you? Freaked out?

Miu-miu: Where did she go?

Anika-voin: What if they really attacked her? Call the cops?

Miu-miu: Aha! We’ll call and say, “At user Rikka’s, IP address unknown, someone is moaning in the kitchen! When we suggested that the dude had a chainsaw, she called us ‘idiots’ and slipped off somewhere.” And we’ll introduce ourselves: Anika-voin and Miu-miu.

Anika-voin: You blockhead! (takes a machine gun and shoots).

Miu-miu: blocks with a frying pan.

Anika voin: bullet will pierce frying pan.

Miu-miu: Fig. See what frying pan.

Irka hurriedly moved the levers, setting the wheels in motion. The wheelchair went in the gloom of the hallway almost noiselessly, but it seemed to Irka that her heartbeats were giving her away – resonant, chaotic, as if a leather-covered tambourine was located inside. She had already guessed the entrance door, which was darker than the walls. Open the lock, then the latch, push the door forward – by no means hard enough that it would hit the wall – and leave carefully. Insert the key outside, turn it once, and then whoever was in the kitchen would not be able to follow her. She would be out of danger and reach the neighbours.

True, the most fearful was ahead: from the kitchen to the door was a short hallway, about three or four steps, no more. And the door could be seen perfectly from the kitchen. One hope was the gloom. If the eyes of the one who had climbed into the kitchen from the brighter street had not gotten accustomed to the darkness, she would have a chance.

Let us repeat once more: lock, latch, pull out the key, leave, insert the key outside, clo…

However, before the chain was completed, the world faltered. Her palm missed the lever, only stumbling everywhere on the rubber elasticity of the tire, and in the next moment, the warm linoleum struck Irka’s cheek. Irka lay, perplexedly contemplating the overturned world. Her head was buzzing. She realized too late that she had caught the edge of the shoe rack, which she usually went around diligently. The darkness had turned from a friend into an enemy.

Understanding that the noise had hopelessly given her away, Irka hurriedly crawled and dragged the wheelchair behind her like the shell of a snail. Her useless traitorous foot – how Irka hated it at this moment! – it goes without saying, had landed between the spokes.

The shoe rack, having managed to conspire with the wheelchair, swayed. Winter boots, tucked away for the summer, bounced merrily. The material world took offence at once and rose up against Irka. This looked tragicomic, at the intersection of gothic and ordinary everyday farce.

A light suddenly blazed in the kitchen. It bore little resemblance to electric light. Bluish, persistent, much brighter, it broke out and illuminated the hallway. Irka’s eyes started to hurt and tear up. The world dazzled with the strips of the painted walls (Granny hated wallpaper) and blinked with the frivolous vases on the wooden shelves.

“Well! Really!” Irka thought, realizing that, lying, still chained to the wheelchair, she would never reach the lock.

After raising herself on her hands, she peered anxiously into the illuminated kitchen, expecting to see a stocky male figure with a crowbar, a flashlight, and a large bag. For some reason, that was how she imagined an apartment thief. But reality shook more than any naive fantasy.

A white she-wolf lay by the table among the broken crockery. The side of the beast directed to Irka was covered with blood. The wolf studied Irka without rage. Sorrow froze in the eyes of the beast.

“Hello! Ah… ah… and I’m crawling here!” Irka said for some reason.

The wolf’s upper lip lifted, baring long yellowish fangs. Blood continued to flow from the wound. It ran along the wet fur in large drops.

“Are you hurt? You poor thing!” Irka said, wondering where the wolf could have been wounded.

Had it cut itself jumping through the kitchen window? But the kitchen window appeared intact. Where could the wolf have come from at all, and even an albino, in the city, on the second floor, with the glass intact? But this was all secondary. Many things are more useful when taken for granted.

Feeling sorry for the beast, Irka tried to crawl up to it, pulling her disobedient body with her hands. She did not think about the frightened, suffering wolf charging. Too much intelligence was in the sad eyes of the beast. When, after jerking up its muzzle, the wolf howled, its howl, low and intermittent, immediately stopped and resembled human speech. As if the wolf wanted to utter something, but, not getting an answer, realized the futility of its undertaking. It tried to get up, but it was unable to. The hind legs of the beast never came off the floor, and it collapsed heavily with its chest onto the linoleum.

They lay this way on the floor for a long time. Two cripples – human and beast— equally helpless. Except that helplessness was familiar to Irka, but the wolf was apparently meeting it for the first time. Irka said some friendly, disjointed and not very coherent words, but the wolf first growled softly, then looked at her expectantly.

Finally, after twisting, Irka successfully freed her foot and escaped from the wheelchair. Without the wheelchair, Irka dragged her disobedient body along the linoleum much faster. The wolf watched her with understanding, not trying to move from the spot. Occasionally it turned its head and licked its wound. However, it was too deep, and the beast only irritated it with its tongue.

“Don’t touch it! We need to seal it up or to call the vet, if only those fools won’t induce sleep in you. Wait, I just… Darn, I won’t reach the table,” Irka muttered, hoping to calm the wolf with the sound of her voice.

Irka had almost crawled to the table when the strange bluish light dimmed, coiled with a mysterious image like a spiral, and enveloped the wolf. The wolf howled, and its howl, growing fainter every moment, was the howl of death. It placed its snout on its paws, continuing to look at Irka. The howl turned into a wheeze and died away. Its eyes became dull and glazed over.

It seemed to Irka that she was delirious. The body of the dead wolf changed. The matted fur with spots of blood more resembled feathers. The snout with bared fangs changed into a white bird’s head with a beak. And here in the middle of the kitchen, a swan was flapping a broken wing, making an effort to take off. The kitchen was tight for the huge bird. The healthy wing touched the table. Finally, exhausted, the swan stopped flapping and, stretching out its neck, issued a throaty, sorrowful sound. This again resembled speech.

“I don’t understand!” Irka said helplessly.

She no longer crawled closer – and froze about a metre or two from the swan, sensing that this was still not the end of the transformation. And she was not mistaken. Suddenly the body of the swan quivered, losing its outlines. Silvery sparks scorched Irka’s face. To save her eyes, she covered them with her hands. When, squinting, she dared to peek, she saw a young woman in a long white robe, half-sitting on the floor. Her collar bone had been fragmented by a terrible blow. The woman was bleeding.

Addressing Irka, she uttered something hoarsely. Irka shook her head, showing that she did not understand. Mild annoyance distorted the truly classically beautiful face of the woman.

“Don’t be afraid of me! I’m a swan maiden,” she repeated in Russian. Her voice sounded throaty and aloof. There was in it something of the howl of the wolf and of the trumpeting of the swan.

“A swan maiden?” Irka asked.

“At times, they call us valkyries.6 Soon I’ll be completely gone. He caught me off guard. I thought he was weak, and I was mistaken. I turned out as weak. The sword had inflicted me a wound, from which I’ll never recover. Two of my essences – the swan and the wolf – have already perished. Now death is getting closer to the last…”

Irka crawled up to the valkyrie. She hardly believed in the reality of the situation and continually glanced down to where her bitten nails were scratching the linoleum. This was the logic: the fingernails were real, the linoleum with onion skin was also more than real. The onion skin and Granny’s eyeglass case lying under the table were too detailed for a dream. But the special liberty and creative fluency, skipping insignificant details, that most daring fluency which always accompanies dreams, did not disappear, confusing Irka.

“Who wounded you?” she asked, putting aside, for the time being, the thought of whether what she was seeing was real or a hallucination caused by the new prescription from the day before.

The valkyrie looked at her sternly. In her tired eyes, continually changing colours, was something poignant, otherworldly. A strange power, authority, and wisdom. On the wall behind the swan maiden, it vaguely seemed to Irka, was a shadow of enormous heft. The worlds opened wide. The worlds were created from dust. Fates intertwined and untwined just like golden hair in a braid.

Finally, the valkyrie looked away. The shadow of heft disappeared. The wall of patterned tiles appeared before Irka in all its dreary banality, flickering beet, carrot, and other idiotic greens.

“Don’t try to find out. Until you’re ready. Your time will yet come!” The maiden coughed. Blood came out of the corners of her lips. “In the pattern of runes of the Sinister Gates there was a single error. One of the runes was not finished, and he knew how, after completing it, to convert it into its own opposite… It was impossible to flee, but he sent his breath out. I stood outside, but saw nothing. It was my fault, since I was his guardian in this century. His breath moved into the messenger’s body, and he wounded me with a sword, which strikes even an immortal. Once this was a sword of Light, and even now, after passing through many rebirths, it has retained its power over us, its creations. I didn’t have time to parry the blow. It was too unexpected to receive it from the one who inflicted it.”

“Whose body did he move into?” Irka quickly asked. For some reason, this seemed important to her, though she did not even know who he was.

“You have asked good questions. Your mind is inquisitive and restless. You’re not one of those living dead, whose heads are empty and whose eyes fade before death. I think I did the right thing choosing you…”

The valkyrie’s voice weakened. Her pupils were losing colour, becoming almost transparent. Irka suddenly realized that the swan maiden’s life was departing together with the colour of her pupils.

“What if we bandage you? Granny has a first-aid kit there…” she said helplessly.

The valkyrie looked at her fragmented collarbone and smiled weakly. “The wounds inflicted by this sword don’t close. Even if it scratched my finger, I would be doomed. Remember the main thing about whom you must stop! You have to come in contact not even with him, but only with his breath. However, there’s also enough force in it to put an end to you. He doesn’t have his own flesh, since it has long become dust, and the wind has scattered it. His spirit is capable of moving into any of the few suitable bodies, crowding its owner. However, while he is in a stranger’s body, his potentials won’t be greater than those of that body. In order to attack in earnest, in full force, he will leave it, and only then will you be able to battle with him. But if he doesn’t leave the body, you’re powerless. Your spear will pierce only the human flesh and its true owner, but not affect the one hiding inside. However, the sin of murdering the guiltless will make you weak, and you no longer will know how to do anything.”

“And how do I recognize him?”

“Don’t worry. It’s impossible not to recognize him. When his breath leaves a body, it’ll become visible even at noon. It’s a spectre of a rider on a red horse. Fight him like you would fight a normal rider. The spectre will be vulnerable to your weapon. But fear his magic: it presents a threat to you, just as the sword that struck me.”

“And if he doesn’t want to leave the body?” Irka asked reasonably.

“Antigonus will help you if he accepts you as his mistress,” the valkyrie replied. A shadow of sadness passed over her pale face. “Perhaps the sword’s blow wouldn’t have caught me unawares had Antigonus been nearby. He’s endowed with the gifts of foresight, expulsion, insight into true essence, and many other abilities.”

“Who’s this Antigonus?” asked Irka. The valkyrie unexpectedly smiled, warmed by some quiet, pleasant thought.

“It’s a most delicate topic. Better not to touch it again. Once a house-spirit fell in love with a kikimora! Love, love! Only whom don’t you catch in your net! True, this wasn’t an entirely pure kikimora! Her maternal grandpa was a vampire, her paternal grandma a mermaid, and paternal grandpa a wood-goblin! Besides, there was even talk of dwarves and Snow White, but that’s doubtful…” she said.

“And?” Irka prompted cautiously.

“Antigonus will become your servant, ally, and adviser. In a favourable situation. True, it’s difficult with Antigonus. Sometimes it’s much simpler without him than with him,” the valkyrie admitted. Cheerfulness went out of her together with life. Her eyes already saw eternity.

“Will I be able to summon him?” Irka asked.

“It’s unnecessary to summon Antigonus. In any case, doing it aloud. At times, it’s sufficient to think of him properly,” the valkyrie replied.

“And how do I think of Antigonus properly?”

The valkyrie shook her head. “I can’t tell you. You must find out by yourself. Otherwise, you’ll never find a common language with Antigonus. Indeed, he’s a terribly strange creature… Now let’s talk about the enemy. About how you’ll find the body which he has moved into…”

The valkyrie’s voice was barely audible. The pauses between the words were increasing. Irka had to keep crawling nearer, straining her ears.

“Not all bodies suit him. There are only four bodies in this world that can accept his essence. One of the four he doesn’t dare touch for the time being… But only for the time being… So, must search among the remaining three…” the valkyrie said. Blood was now barely flowing from the wound. Her face was becoming grey.

“She’s dying!” Irka realized with sudden clarity.

“Don’t be alarmed! Demigods don’t depart without a trace. They can’t leave this world without passing on immortality and gift,” the valkyrie said, after reading her thoughts. “Take my winged helmet!”

“Helmet?” Irka repeated, looking around. She did not see a helmet.

The swan maiden coughed. The blood, which earlier bubbled in the corners of her lips, ran down her cheek. Irka crawled up to the valkyrie. The swan maiden, quite weakened, carefully lay down on her back, helping herself with her good hand. Her long bright hair sprawled over the linoleum. Irka involuntarily thought how strange they both looked. Two half-beings – one dying and one crippled – in the kitchen of the most ordinary home, on the floor flooded with blood, were discussing the fate of the world and the escape of an unknown essence from the Sinister Gates.

“When you need to, you’ll see it and take my place! Stop the messenger, before he acquires power… Don’t let him catch you unawares. Don’t repeat my mistake!” The valkyrie spoke each new word with difficulty; blood pushed out of her throat together with the sounds. “There is little time… Swear on your eidos to Light that you’ll assume my gift and carry it to eternity, until your breath disappears. Without this the helmet won’t become yours.”

“But what’s this eidos?” Irka asked carefully. To swear on something she did not know existed seemed to her unreasonable. Something stirred imperceptibly in her chest, prompting the answer. “I swear!” Irka said, obeying the prompt, but immediately added dubiously, “But how can I stop someone… In this idiotic wheelchair I can’t even go down the steps without Granny’s help.”

The valkyrie’s lips trembled, attempting to form into a smile. With a weak motion of her hand she ordered Irka to keep silent. “It… doesn’t… matter… Don’t get distracted by trifles. We should have time for everything. Si fata sinant [If fate would have it (Lat.)]. Don’t fret about the disability. I’m taking on your pain! The scars on your back, your lifeless legs… I accept them as a gift in return. Will you agree to transfer them to me?” the valkyrie said.

“Yes,” Irka quickly said, sharply feeling all the nastiness of this answer.

The swan maiden chanted something droningly. It was impossible to repeat this chant. It was anything but human speech. Like a tiger’s growl, a wolf’s howl, a falcon’s screech…

The last sound had barely stopped and the valkyrie turned heavily on her side. Irka saw that her white robe was stained with blood on the back. Two long bloody strips went precisely where Irka’s scars were. Irka cried out.

With a gesture, the valkyrie forbade her to approach. “Redemption! Punishment for evil I committed long ago!” the valkyrie uttered hoarsely. “The load of grief and happiness is measured out to each in advance. Nothing can simply disappear. The pain, having disappeared in one, will arise in another. I took your load, nothing more.”

“But why?” Irka shouted, with involuntary happiness feeling her legs warming up. It was a new feeling, vague, joyful. As if spring sap was running through a dead dry tree.

“Don’t thank me! I won’t carry another’s burden for long. My sun is setting, yours is at dawn,” the valkyrie smiled. “When one valkyrie leaves, another must arrive. Soon your body will renew, the wounds will heal… Lean over! Closer… Still… You’ll receive my last breath! With it I’ll transfer my power to you! I don’t think that you’ll get the entire gift at once, but gradually it’ll come to you… And most important: at this moment, don’t think about anything else! Your mind must be as empty and beautiful as crystal glass. This is necessary so that the regeneration will begin…”

Irka wanted to state that she had no idea how to receive a breath, but the valkyrie did not hear her. “Si ferrum non sanat, ignis sanat [If iron does not heal, fire heals (Lat.)]. Sic vos non vobis vellera fertis, oves. Sic vos non vobis mellificatis, apes. Sic vos non vobis fertis aratra, boves [So not for yourselves bear fleeces, you sheep. So not for yourselves make honey, you bees. So you not for yourselves draw ploughs, you oxen (Lat.)],”7 she muttered.

The valkyrie’s voice was barely audible, fading. Irka concentrated. She did not know how to accept the last breath and feared doing something wrong. Suddenly she saw a hazy pink radiance shrouding the valkyrie’s head. An indistinct bright spectre detached itself from her lips. After looking intently, Irka discerned the miniature figure of a woman in a helmet and a shining breastplate with a spear in her hand. Turning into a sweetish smoke, it slid towards the girl’s face.

“Here it is now…” Irka thought. “What must I do? Aha, not to think about anything else. Just imagine a crystal glass?”

She began to honestly visualize a glass, but, as always happens with imagination, it was obstinate and, instead of a glass, produced a glass with tomato juice stains. The spectre of the woman in a helmet approached her lips and froze, and shook its head reproachfully, as if in doubt. Then, already beginning to dissipate, it moved forward. Against her will, Irka inhaled deeply, sensing something unfamiliar merging with her and becoming a part of her.

Irka was suddenly seized by rapture, which she did not deem necessary to hide. For a brief moment she felt enormous, absorbing all the secrets of the earth, the underground, and the ocean floor. The interlaced tangle of parallel worlds and the taut, rigid spirals of time, like the springs of a clock, everything had become as natural to her as the arrangement of rooms in the apartment.

Irka laughed, and her laughter swept over Moscow in July like a sudden peal of thunder. An instant hurricane roughed up lawns, tossed dust on the embankment, rattled signs, broke several windows, overturned tables in a summer cafe, and swept and whirled old newspapers. Moronoids stopped and squinted at the clear sky with alarm. Some routinely checked the umbrellas in their bags to see whether they were buried in the things and whether they would open quickly. Their movements were mechanical and precise, like a soldier checking whether his sword is stuck in the scabbard.

“Greetings, new valkyrie! Hush, quieter! Not so frisky! Reserve the magic!” Irka heard the barely audible sad voice. Coming to her senses, Irka stopped laughing. The sensation of omnipotence disappeared. Irka understood that she had needlessly wasted power, which should only be resorted to out of necessity.

In front of her on the kitchen floor, a young woman, who had given Irka her own power, was dying from a wound. Now that her magic had left, her helplessness was manifested in everything. Especially pitiful were the thin, weak, absurdly twisted legs. And Irka felt it so sharply that, despite her present might, she would not be able to help. Sensing her dismay, the swan maiden smiled weakly. “And who must encourage whom? She’s stronger than me in spirit even now!" Irka thought with shame.

“Now’s not the time for tears. Be careful turning into a wolf or a swan. This gift is very rare. I alone of all of the valkyries have it. At times it’s convenient, but remember that in doing so, part of your intellect retires and is replaced by that of the bird or the wolf. It’s not dangerous while you predominate, but sometimes, the element can overwhelm you. Always recognize where your will finishes and the desires of the beast and the bird begin. This is monstrously important. You won’t forget?”

“No.”

“Remember something else! None who knew you before should learn the secret of who you are in reality. You won’t be able to reveal it to them either under torture, in times of happiness, or in a moment of anger… From now on, you’re a valkyrie. The previous Irka no longer exists. Your past is known only to you and me.”

“Yes, but if so, then…” Irka began.

“To your grandmother, you’re a cripple as before, chained to the wheelchair. No one is in the state to get to your secret while you guard it,” the valkyrie said impatiently.

“But if I don’t?” Irka asked.

“If you don’t, the one who hears it, even by chance, will lose his mind and die. And it doesn’t matter who this will be: a relative, a casual acquaintance, or a loved one. Death won’t bypass him.”

“I also can never tell Methodius?” Irka asked, unexpectedly for herself. She wanted to say “And Granny?”, but instead Methodius came out for some reason.

The question provoked the swan maiden’s displeasure. And the displeasure, as it seemed to Irka, was connected precisely with the name she heard.

“Especially not him! A valkyrie can only reveal to the one she transfers the gift. And now good-bye! Illi robur et aes triplex [There oak and triple bronze (Lat.)]…”8 A major shudder passed through the valkyrie’s body and it suddenly disappeared. A merry joyous ringing hung in the air, similar to the sound of a distant bell or spring drops falling sonorously on a sheet of iron.