Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Legacy of the Bones»

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Dolores Redondo 2013

Translation copyright © Nick Caistor and Lorenza García 2016

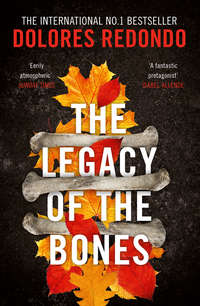

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Dolores Redondo asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Originally published in 2013 by Ediciones Destino,

Spain, as Legado en los huesos

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2016 ISBN: 9780008165604

Version: 2018-10-26

Dedication

For Eduardo, every word.

Epigraph

Has this fellow no feeling of his business?

He sings at grave-making.

William Shakespeare

Often the sepulchre encloses, unawares,

Two hearts in the same coffin.

Alphonse De Lamartine

Pain when inside is stronger

It isn’t eased by sharing.

Alejandro Sanz, ‘Si Hay Dios’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Itxusuria

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Footnotes

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Exclusive extract from Offering to the Storm

If you enjoyed The Legacy of the Bones, read the first book in the Baztan trilogy …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Itxusuria

Following the line traced by rainwater dripping from the eaves, the grave was easy to find. The figure knelt, fumbling among its clothes for a trowel and a small pick to scrape off the hard surface of the dark soil. It crumbled into soft, moist clods that gave off a rich smell of wood and moss.

A careful scraping of a few centimetres revealed blackened shreds of decayed cloth mixed with the earth.

The figure tugged away the cloth, still recognisable as a cot blanket, to reveal the oilskin enshrouding the body. Only fragments of the rope securing the bundle remained; where it had been pulled tight a deep mark was left on the canvas. Pushing aside the shreds of rope, the figure groped blindly for the edge of the cloth, and could feel it had been wrapped round several times. Tearing at the end of the bundle, the shroud fell open as though cut with a knife.

The baby lay buried face down, cradled in the earth; the bones, like the oilcloth itself, appeared well preserved, although stained by the black earth of Baztán. Stretching out a hand that almost completely covered the tiny form, the figure pressed the baby’s chest further into the earth and pulled the right arm out of its socket. As it came loose, the collarbone snapped with a soft crack. It sounded like a sigh from the tomb, a lament for the sacrilege. Suddenly uneasy, the shadowy figure recoiled and stood up, tucked the bones under its clothes, then cast one last glance at the body before scuffing the soil back into the grave.

1

The atmosphere in the courthouse was stifling. The damp from rain-soaked overcoats was starting to evaporate, mixing with the breath of the hundreds of people thronging the corridors outside the various courtrooms. Amaia undid her jacket as she greeted Lieutenant Padua, who made his way towards her through the waiting crowd, after speaking briefly to the woman accompanying him and ushering her into the courtroom.

‘Good to see you, Inspector,’ he said. ‘How are you? I wasn’t sure you’d make it here today,’ he added, pointing to her swollen belly.

Amaia raised a hand to her midriff, heavy from the late stages of pregnancy.

‘Well, she seems to be behaving herself for the moment. Have you seen Johana’s mother?’

‘Yes, she’s pretty nervous. She’s inside with her family. They’ve just called from downstairs to tell me the van transporting Jasón Medina has arrived,’ he said, heading for the lift.

Amaia entered the courtroom and sat down on one of the benches at the back. From there she was able to glimpse Johana’s mother, dressed in mourning and considerably thinner than at her daughter’s funeral. As though sensing her presence, the woman turned to look, greeting her with a brief nod. Amaia tried unsuccessfully to smile as she contemplated the haggard features of the woman, who was tormented by the knowledge that she had been powerless to protect her daughter from the monster she herself had brought into their home. As the court clerk began to call out the names of the witnesses, Amaia couldn’t help noticing the woman’s face stiffen when she heard her husband’s name.

‘Jasón Medina,’ the clerk repeated. ‘Jasón Medina.’

A uniformed officer entered the courtroom, approached the clerk and whispered something in his ear. He in turn leaned over to speak to the judge, who listened to what he said then nodded, before calling the prosecution and defence barristers to the bench. He spoke to them briefly then rose to his feet.

‘The trial is adjourned; if necessary, you will be summoned again.’ And without another word, he left the courtroom.

Johana’s mother cried out, turning to Amaia for an explanation.

‘No!’ she screamed. ‘Why?’

The women with her tried helplessly to comfort her.

Another officer walked over to Amaia.

‘Inspector Salazar, Lieutenant Padua has asked if you would go down to the holding cells.’

As she stepped out of the lift, she saw a group of police officers gathered outside the toilet door. The guard accompanying her motioned to her to enter. Inside, a prison officer and a policeman stood propped against the wall, their faces distraught. Padua was leaning into one of the cubicles, his feet at the edge of a pool of still fresh blood seeping under the partition walls. When he saw the inspector arrive, he stepped aside.

‘He told the guard he needed to use the toilet. As you can see, he was handcuffed, yet he managed to slit his own throat. It all happened very fast, the officer didn’t move from here, heard him cough and went in, but there was nothing he could do.’

Amaia went in to survey the scene. Jasón Medina was sitting on the toilet, head tilted back. His throat was gaping from a deep, dark gash. His shirtfront was drenched in blood, which oozed like red mucus between his legs, staining everything in its path. His body still radiated warmth, and the air was tainted with the smell of recent death.

‘What did he use?’ asked Amaia, who couldn’t see any object.

‘A box cutter. He dropped it as the strength drained out of him. It’s in the next-door toilet,’ he said, pushing open the door to the adjacent cubicle.

‘How did he get it through security? The metal would have set the alarm off.’

‘He didn’t. Look,’ said Padua, pointing. ‘See that piece of duct tape on the handle? Somebody went to a lot of trouble to hide the cutter in here, no doubt behind the cistern. All Medina had to do was peel it off.’

Amaia sighed.

‘And there’s more,’ said Padua, with a look of distaste. ‘This was sticking out of his pocket,’ he said, holding up a white envelope in his gloved hand.

‘A suicide note?’ ventured Amaia.

‘Not exactly,’ said Padua, handing her a pair of gloves and the envelope. ‘It’s addressed to you.’

‘To me?’ Amaia frowned.

She pulled on the gloves and took the envelope.

‘May I?’

‘Go ahead.’

The adhesive strip opened easily without her needing to tear the paper. Inside was a card; in the middle of it a single word was printed.

‘Tarttalo.’

Amaia felt a sharp twinge in her belly and held her breath to disguise the pain. She turned the card over to make sure nothing was written on the back, before returning it to Padua.

‘What does it mean?’

‘I was hoping you’d tell me.’

‘Well, I’ve no idea, Lieutenant Padua,’ she replied, puzzled. ‘It doesn’t make much sense to me.’

‘A tarttalo is a mythological creature, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, as far as I know it’s a kind of Cyclops. It exists in both Graeco-Roman and Basque mythology. What are you getting at?’

‘You worked on the basajaun case. The basajaun was also a mythological creature, and now Johana Márquez’s confessed murderer, who tried to copy one of the basajaun crimes to conceal his own, kills himself and leaves a note that says: “Tarttalo”. You must admit it’s curious, to say the least.’

‘You’re right.’ Amaia sighed. ‘It’s strange. However, at the time we proved beyond doubt that Jasón Medina raped and murdered his stepdaughter, then made a clumsy attempt to pass it off as one of the basajaun crimes. Not only that, he made a full confession. Are you suggesting he wasn’t the murderer?’

‘I don’t doubt it for a minute,’ said Padua, glancing at the corpse. ‘But there’s the question of the severed arm, and the girl’s bones turning up in the Arri Zahar cave. And now this. I was hoping you might …’

‘I’ve no idea what this means, or why he addressed it to me.’

Padua gave a sigh, his eyes fixed on her.

‘Of course not, Inspector.’

Amaia headed for the rear exit, anxious not to bump into Johana’s mother. What could she say to the woman: that it was all over, or that her husband, like the rat he was, had escaped to the next world? She flashed her ID at the security guards; it came as a relief to be free at last of the atmosphere inside. The rain had stopped and the bright yet hesitant sunlight, typical in Pamplona between showers, emerged through the clouds, making her eyes water as she rummaged in her bag for her dark glasses. As ever when it was raining, finding a taxi to take her to the courthouse during the morning rush hour had been almost impossible; but now several of them sat idling at the rank, while the city’s inhabitants chose to walk. She hesitated for a moment beside the first car. No, she wasn’t quite ready to go home; the prospect of Clarice running around, bombarding her with questions was decidedly unappealing. Since her in-laws had arrived a fortnight earlier, Amaia’s idea of home had been seriously challenged. She gazed towards the enticing windows of the cafés across from the courthouse and at the other end of Calle San Roque, where she could see the trees in Media Luna Park. Working out that it was roughly one and a half kilometres to her house, she set off on foot. She could always hail a taxi if she felt tired.

Leaving behind the roar of traffic as she entered the park gave her an instant sense of relief. The fresh scent of wet grass replaced the exhaust fumes, and Amaia instinctively slackened her pace as she crossed one of the stone paths that cut through the perfect greenness. She took deep breaths, exhaling with deliberate slowness. What a morning, she thought; Jasón Medina perfectly fitted the profile of the criminal who commits suicide in jail. Accused of raping and killing his wife’s daughter, he had been put in solitary confinement pending his trial; no doubt he’d been terrified at the prospect of having to mix with other prisoners after being sentenced. She remembered him from the interrogations nine months earlier, when they were investigating the basajaun case: a snivelling coward, weeping and wailing as he confessed his atrocities.

The two cases weren’t connected, but Lieutenant Padua of the Guardia Civil had invited her to sit in, because of Medina’s clumsy attempts to imitate the modus operandi of the serial killer she was chasing, based on what he had read in the newspapers. That was nine months ago, just when she became pregnant. Since then, a lot of things had changed.

‘Haven’t they, little one?’ she whispered, stroking her belly.

A violent contraction caused her to pull up short. Leaning on her umbrella for support, she doubled over, enduring the terrible spasm in her lower abdomen, which spread in a ripple down her inner thighs, wrenching a cry from her, more of surprise at the intensity than of pain. The sensation subsided as quickly as it had arisen.

So that’s how it felt. Countless times she had wondered what it would feel like to go into labour, whether she would recognise the signs, or be one of those women who arrived at the hospital with the baby already crowning, or who gave birth in the taxi.

‘Oh, my little one!’ Amaia spoke to her sweetly. ‘You still have another week. Are you sure you want to come out now?’

The pain had vanished, as if it had never happened. She felt an immense joy, accompanied by a twinge of anxiety at the imminence of her baby’s arrival. She smiled, glancing about as if she wished she could share her pleasure. But the moist, cool park was deserted and its emerald green colours, still more radiant and beautiful in the dazzling light seeping through the clouds above Pamplona, reminded her of the sense of discovery she always felt in Baztán, which in the city seemed like an unexpected gift. She continued on her way, transported now to that magical forest and the amber eyes of the lord of that domain. Only nine months previously she had been investigating a case there, in the place where she was born, the place she had always wanted to flee, the place where she had gone to hunt down a killer, and where she conceived her baby girl.

The knowledge that her daughter was growing inside her had brought the soothing calm and serenity to her life that she had always dreamt of. At that time it had been the only thing that helped her cope with the terrible events she had lived through, which a few months earlier would have been the death of her. Returning to Elizondo, dredging up her past, and, most of all, Víctor’s death, had turned her world and that of her entire family upside down. Aunt Engrasi was the only one unaffected, reading her tarot cards, playing poker with her women friends every afternoon, smiling like someone who has seen everything before. Overnight, Flora had moved to Zarautz, on the pretext of recording her daily programme on baking for national television, and, who would have believed it, had handed over the running of Mantecadas Salazar to Ros. Much to Flora’s astonishment – and confirming Amaia’s intuitions – Ros had turned out to be a first-class manager, if a little overwhelmed to begin with. Amaia had offered to help her out and for the past few months had been spending almost every weekend in Elizondo, even after she realised that Ros no longer needed her support. And yet she continued to go there, to eat with them, to sleep at her aunt’s house, feeling at home. From the moment her baby girl started to grow inside her, she’d begun to rediscover a feeling of home, of roots, of belonging, that for years she thought she had lost for ever.

As she came out into Calle Mayor it began to drizzle again. She opened her umbrella, picking her way between the shoppers and a few pedestrians who had no protection and were scurrying along beneath the eaves of the buildings and shop awnings. She paused in front of the colourful window of a store selling children’s clothes and contemplated the little pink smocks embroidered with tiny flowers. Clarice was probably right, she ought to buy something like that for her baby. She sighed, all of a sudden irritated, as she thought of the room Clarice had decorated for her child. James’s parents had come over from the States for the birth and after only ten days in Pamplona his mother had more than fulfilled Amaia’s worst expectations of what a meddlesome mother-in-law could be like. From the very first day, she voiced her bewilderment about there being no nursery despite all the spare rooms they had.

Amaia had salvaged an antique hardwood cot from her Aunt Engrasi’s sitting room, where for years it had been used as a log basket. James had sanded it down to the grain before applying a fresh coat of varnish, while Engrasi’s friends had made an exquisite valance and a white bedcover that accentuated the craftsmanship and character of the cot. There was plenty of space in their large bedroom; besides, despite what the experts said, Amaia wasn’t convinced about the merits of her baby having a separate room; for the first few months, while she was breastfeeding, having the baby nearby would make it easier to feed her during the night, and knowing that she could hear her if she cried or had a problem would reassure her …

Clarice had raised the roof. ‘The baby must have her own room, with all her things around her. Believe you me, both mother and baby will sleep better. If you have her next to you, you’ll be listening for her every breath and movement; she needs her space and you need yours. Anyway, it’s not healthy for a baby to share its parents’ bedroom, children become used to it and won’t be taken to their own room.’

Amaia had also read the advice of a host of celebrated paediatricians determined to indoctrinate an entire new generation of children into the ways of suffering: don’t pick them up too often, let them sleep alone from birth, don’t comfort them when they have a tantrum because they need to learn to be independent, to cope with their fears and failures. Such stupidity made Amaia’s stomach churn. It occurred to her that if any of these distinguished doctors had been obliged since birth to ‘cope’ with fear the way she had, they would have an entirely different view of the world. If her daughter wanted to sleep in their bedroom until she was three years old, that was fine by her: she would comfort her, listen to her, take seriously and allay her childish fears, because as she herself knew only too well, they could loom large in a child’s mind. But evidently Clarice had her own ideas about how things should be done, which she didn’t hesitate to share with everybody else.

Three days earlier, Amaia had arrived home to discover that her mother-in-law had given them a surprise gift: a magnificent nursery complete with wardrobes, a changer, chest of drawers, rugs, and lamps. A superabundance of pink fleecy clouds and little lambs, all wreathed in ribbons and lace. Amaia had been alarmed enough when James had opened the door, given her a kiss and whispered apologetically: ‘She means well.’ But when she was confronted by this profusion of pinkness, her smile froze as she realised she was being made to feel like a stranger in her own home. Clarice, on the other hand, was thrilled, gliding amidst the furniture like a TV presenter, while Amaia’s father-in-law, impassive as always when faced with his wife’s enthusiasm, carried on calmly reading the newspaper in the sitting room. Amaia found it difficult to reconcile the image of Thomas at the helm of a financial empire with the way he behaved towards his wife, with a mixture of submissiveness and apathy that never ceased to amaze her. If only because she knew how uncomfortable James felt, Amaia did her best to keep her composure while his mother extolled the marvels of the nursery she had bought for them.

‘Look at this lovely wardrobe, all her clothes will fit in there, and there is room in the changer for nappies as well as everything else. Aren’t the rugs cute? And over here,’ she said, grinning smugly, ‘the pièce de résistance: a cot fit for a princess.’

Amaia had to admit that the huge pink cot was indeed majestic, and big enough for her daughter to sleep in until she was at least four years old.

‘Very pretty,’ she forced herself to say.

‘It’s beautiful, so now you can give your aunt back her log basket.’

Amaia left the nursery without a word and went into her bedroom to wait for James.

‘Oh, I’m sorry, sweetheart, she doesn’t mean to interfere, it’s just how she is. They’ll only be here a few more days. I know you’re being incredibly patient, and I promise you that after they’ve gone we’ll get rid of everything you don’t like.’

She had agreed for James’s sake and because she didn’t have the strength to argue with Clarice. James was right: she was being incredibly patient, even though it went against her nature. This was possibly the first time she had ever let anyone control her, but in this final stage of pregnancy, she had noticed a change come over her. For days now she had been feeling unwell; all the energy she had enjoyed during the first months had given way to an apathy that was unusual in her. Clarice’s domineering presence only brought that fragility to the fore. Amaia glanced again at the baby clothes in the shop window and decided they had quite enough with everything her mother-in-law had bought. Clarice’s extravagances as a first-time grandmother made Amaia feel queasy, but there was something else: secretly she would have given anything to have the same intoxicating love affair with pink that afflicted her mother-in-law.

Since she had become pregnant, all she had bought for her daughter was a pair of bootees, a few T-shirts, some leggings, and a set of Babygros in neutral colours. She told herself that pink wasn’t her favourite colour. When she browsed the shop windows and saw frocks, cardigans and skirts bedecked with ribbons and embroidered flowers, she thought they looked lovely, perfect for a little princess, but no sooner did she have them in her hand than she felt an intense aversion towards all those tasteless frills and ended up walking out, confused and irritated, without buying anything. She could have done with some of the enthusiasm shown by Clarice, who would dissolve into raptures at the sight of a frock and matching shoes. Amaia knew that she couldn’t have been happier, that she had always loved this baby, from the time when she herself had been a brooding, unhappy child dreaming of being a mother one day, a real mother, a desire that had crystallised when she met James. And when motherhood threatened to elude her, assailed with fears and doubts, she had considered undergoing IVF treatment. But then, nine months ago, while investigating the most important case of her career, she had become pregnant.

Amaia was happy, or at least thought she was, and that puzzled her even more. Until recently she had felt fulfilled, contented, self-assured in a way that she hadn’t for years; yet over the past few weeks, fresh fears, which were actually as old as time, had started creeping back, infiltrating her dreams, whispering familiar words she wished she didn’t recognise.

Another contraction, less painful but more drawn-out, gripped her. She checked her watch. Twenty minutes since the last one in the park.

She headed towards the restaurant where they had arranged to meet. Clarice didn’t approve of James cooking all the time, and kept hinting that they needed staff. Half-expecting to arrive home one day to find they had an English butler, she and James had decided they should lunch and dine out every day.

James had chosen a modern restaurant in the street next to Calle Mercaderes, where they lived. When she arrived, Clarice and the taciturn Thomas were both sipping martinis. James stood up as soon as he saw her.

‘Hi, Amaia, how are you, my love?’ he said, planting a kiss on her lips and pulling out a chair for her.

‘Fine,’ she said, wondering whether to mention the contractions. She glanced at Clarice and decided to keep quiet.

‘And the little one?’ James smiled, resting his hand on her belly.

‘The little one,’ repeated Clarice derisively. ‘Do you think it’s normal that a week before your daughter’s birth you still haven’t chosen a name for her?’

Amaia pretended to browse the menu while looking askance at James.

‘Oh, Mom, not that again. We like several, but we can’t decide, so we’re waiting until the baby arrives. The moment we see her little face we’ll know what to call her.’

‘Oh!’ Clarice perked up. ‘So, you have thought of some names. Is one of them Clarice, maybe?’ Amaia heaved a sigh. ‘Seriously, though what names are you thinking of?’ Clarice persisted.

Amaia glanced up from the menu as a fresh contraction gripped her belly for a few seconds. She looked at her watch again and smiled.

‘Actually, I’ve already chosen one,’ she lied, ‘only I want it to be a surprise. What I can tell you is that she won’t be called Clarice: I don’t like names repeated within families, I think each person should have their own identity.’

Clarice grimaced.

The baby’s name was another missile Clarice fired at her whenever she got the opportunity. James’s mother had harped on about it so much that he had even suggested they choose one just to shut her up. Amaia had snapped. That was the last straw: why should she be forced to choose a name simply to make Clarice happy?

‘Not to make her happy, Amaia, but because we have to call her something, and you don’t seem to want to think about choosing a name at all.’

As with the clothes, she knew they were right. Having researched the subject, she’d become so concerned about it that she consulted Aunt Engrasi.

‘Well, not having had babies myself, I can’t speak from personal experience, but at a clinical level, I gather it’s fairly common among first-time mothers and fathers in particular. Once you’ve had a baby, you know what to expect, there are no surprises, but with a first pregnancy some mothers, despite their swollen bellies, find it hard to relate the changes in their body to the realities of having a child. Nowadays with ultrasound and listening to the baby’s heartbeat, knowing if it’s a boy or a girl, expectant parents have more of a sense that their baby is real, whereas in the past you couldn’t see a baby until it was born; most people only realised they had a child when they were cradling it in their arms and gazing into its little face. Your misgivings are perfectly natural,’ she said, placing her hand on Amaia’s belly. ‘Believe me, no one is prepared for parenthood, although some people like to pretend that they are.’

Amaia ordered fish, which she hardly touched. She noticed that the contractions were less frequent and less intense when she was still.

As soon as they’d finished their meal, Clarice returned to the offensive.

‘Have you looked at crèches?’

‘No, Mom, we haven’t,’ said James, setting his cup down on the table and gazing at her wearily. ‘Because we’re not putting the baby in a crèche.’

‘I see, so you’ll find a child-minder when Amaia goes back to work.’

‘When Amaia goes back to work, I’ll look after my daughter myself.’

Clarice’s eyes opened wide. She looked to her husband for support, but received none from Thomas, who smiled and shook his head as he sipped his rooibos.

‘Clarice …’ he cautioned. These gentle repetitions of his wife’s name in a tone of reproach were the closest Thomas ever came to protesting.

She ignored him.

‘You can’t be serious. How are you going to look after her? You don’t know the first thing about babies.’

‘I’ll learn,’ James replied, smiling.

‘Learn? For goodness’ sake! You’re gonna need help.’

‘We have a cleaner who comes regularly.’

‘I’m not talking about a cleaner four hours a week, I’m talking about a nanny, a child-minder, someone who’ll take care of the child.’

‘I’ll take care of her. We’ll take care of her together, that’s what we have decided.’

James seemed amused, and, judging from his expression, so did Thomas. Clarice sighed, smiled wanly and adopted a calm tone, as though making a supreme effort to be reasonable and patient.

‘Yes, I know all about this modern parenting stuff – breastfeeding children until they grow teeth, having them sleep in your bed, dispensing with a nanny – but, son, you have to work too, your career is at a critical stage, and during the baby’s first year, you’ll scarcely have time to draw breath.’